Takatta Loa: Difference between revisions

Takatta Loa (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary Tag: 2017 source edit |

Takatta Loa (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary Tag: 2017 source edit |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

* Isi Loa | * Isi Loa | ||

* Safa Loa | * Safa Loa | ||

* | * Masa Loa | ||

* | * Ahoso Loa | ||

* | * Highland Loa | ||

* Non-Loa Polynesians | |||

|ethnic_groups_year = 2030 | |ethnic_groups_year = 2030 | ||

|religion = [[Kapuhenasa]] | |religion = [[Kapuhenasa]] | ||

| Line 108: | Line 109: | ||

These palaces were, at any given time, six of a few dozen or so, and were simply the ones who exerted the most influence. Later writings confirm this, indicating that they received tribute from subordinate palaces. The income from the vassal palaces varied depending on region, but typically consisted of crops or slaves, as well as cowrie shells. Certain palaces, especially Aiaka from 750 CE to 830 CE, amassed such prestige and influence that goods from across the entirety of Takatta Loa, including feathers from the Loa Islands, have been found in the palatial tombs, which were built very far from the site of modern day Disa’adakuo. However, their control was marginal beyond receiving taxes and despite the large armies they often claimed to have, there is very little evidence of warfare during this time. Instead, palaces seemed to have risen and fallen into and from prominence organically as the families that constituted the palaces naturally grew into influence and disintegrated. | These palaces were, at any given time, six of a few dozen or so, and were simply the ones who exerted the most influence. Later writings confirm this, indicating that they received tribute from subordinate palaces. The income from the vassal palaces varied depending on region, but typically consisted of crops or slaves, as well as cowrie shells. Certain palaces, especially Aiaka from 750 CE to 830 CE, amassed such prestige and influence that goods from across the entirety of Takatta Loa, including feathers from the Loa Islands, have been found in the palatial tombs, which were built very far from the site of modern day Disa’adakuo. However, their control was marginal beyond receiving taxes and despite the large armies they often claimed to have, there is very little evidence of warfare during this time. Instead, palaces seemed to have risen and fallen into and from prominence organically as the families that constituted the palaces naturally grew into influence and disintegrated. | ||

The control of the palaces rarely extended to the internal politics of any subordinate palaces, and this would end up being the reason for the collapse of the palatial cultures and the beginning of the Takatta Loa medieval age. From 700 to 900 CE, there were a series of incredible innovations that would lead to both the enrichment and development of mainland cultures, and the collapse of the palaces. The first major development was the genesis of the Loa scripts, which had since the 400s been slowly developing from pre-literate glyphs to a fully fledged writing system. The speed of this development is remarkable | The control of the palaces rarely extended to the internal politics of any subordinate palaces, and this would end up being the reason for the collapse of the palatial cultures and the beginning of the Takatta Loa medieval age. From 700 to 900 CE, there were a series of incredible innovations that would lead to both the enrichment and development of mainland cultures, and the collapse of the palaces. The first major development was the genesis of the Loa scripts, which had since the 400s been slowly developing from pre-literate glyphs to a fully-fledged writing system. The speed of this development is remarkable but is generally assumed to have been influenced by the Latin script, as [[Caphiria| Caphiric]] artifacts have been found in the region around this time. However, the Loa scripts, tentatively called the Rongorongo scripts by emerging researchers, are thought to have not been derived from any occidental script but rather been a deliberate attempt to create a script from existing glyphs. One theory is that the palaces or one palaces in particular, created the script in order to control the language of trade in the region and prevent Caphiric scripts from taking root and potentially allowing power to shift into a merchant class. The fact that palaces would allow merchants to be educated in the (perhaps deliberately) convoluted logographic system for free suggests that this may be the case, as well as the bizarre and recurring phenomenon where the rulers of a palace boast in a stele or wall panel about how they “commanded the voice ... [and] bound the spirits [with it]”. This is thought to be a poetic interpretation of controlling trade through developing a system of keeping track of goods, as the Polynesians interpreted spirits as controlling fortunes. | ||

Despite its potential outside influence, literacy became an extremely influential aspect of palatial society at the time, with people very quickly realizing its use in poetry and general communication. Spiritual aspects as seen above became associated with writing, and since the palaces controlled literacy, this allowed them extensive control over the religious landscape of their domains. | Despite its potential outside influence, literacy became an extremely influential aspect of palatial society at the time, with people very quickly realizing its use in poetry and general communication. Spiritual aspects as seen above became associated with writing, and since the palaces controlled literacy, this allowed them extensive control over the religious landscape of their domains. | ||

| Line 120: | Line 121: | ||

==Government and Politics== | ==Government and Politics== | ||

Takatta Loa is a constitutional theocracy with a semi-bicameral legislature. The divine spirit Natano is the official head of state according to the constitution, although he speaks through his human representative in the mundane realm. This means that in practice, the Incarnate of the Order of Natano is the head of state, although they have largely ceremonial powers and little impact on government, with the powers of government lying in the Four Houses. The upper house is divided into the Houses of Orders and Queens, with 14 and 12 members respectively for a combined total of 26 members of the two upper houses. The lower house is divided into the Houses of Commons and Chieftains, with 500 legislators in each, for a combined total of 1,000 legislators. The upper and lower houses have divided legislative, taxation and budget setting duties, as well as divided duties for appointing the higher government officials. The actual administration of the government is done by the Ten Ministries system, whose High Ministers are elected from among and by the employees of the ministries and whose supporting cabinet of coordinators are appointed by the legislature. Government officials are selected via an internship and examination system, and are then typically promoted from within | |||

===Law=== | ===Law=== | ||

==Demographics== | ==Demographics== | ||

| Line 130: | Line 132: | ||

| other = | | other = | ||

| label1 = | | label1 = Isi Loa | ||

| value1 = | | value1 = 12.5 | ||

| color1 = | | color1 = Brown | ||

| label2 = | | label2 = Ahoso Loa | ||

| value2 = | | value2 = 36.6 | ||

| color2 = | | color2 = Pink | ||

| label3 = | | label3 = Safa Loa | ||

| value3 = | | value3 = 23.7 | ||

| color3 = | | color3 = LimeGreen | ||

| label4 = | | label4 = Masa Loa | ||

| value4 = | | value4 = 15.4 | ||

| color4 = | | color4 = NavajoWhite | ||

| label5 = | | label5 = Highland Loa | ||

| value5 = | | value5 = 10.7 | ||

| color5 = | | color5 = CadetBlue | ||

| label6 = | | label6 = Other | ||

| value6 = | | value6 = 1 | ||

| color6 = | | color6 = LightYellow | ||

}} | }} | ||

| Line 163: | Line 162: | ||

| other = | | other = | ||

| label1 = [[]] | | label1 = [[Kapuhenasa]] | ||

| value1 = | | value1 = 70 | ||

| color1 = | | color1 = Brown | ||

| label2 = | | label2 = Islam | ||

| value2 = | | value2 = 28 | ||

| color2 = | | color2 = LimeGreen | ||

| label3 = | | label3 = Other | ||

| value3 = | | value3 = 2 | ||

| color3 = | | color3 = NavajoWhite | ||

}} | }} | ||

===Education=== | ===Education=== | ||

Education in Takatta Loa is available in either public or religious schools, both of which follow the state mandated 13 year program, starting at age 5. Students go through 5 years of primary education followed by 8 years of secondary education and then students can choose whether to pursue a trade or higher education or neither. Classes for primary education in public schools include Mathematics, Literacy, Cultural studies, Physical Education and Secular Sciences. Secondary school includes more advanced studies of the above, as well as Takatta Loa History, World history, Religious studies and Loa cultural studies as mandated courses, with electives including such things as Music theory, Medicine, Muslim studies, Arabic language, Forestry, etc. Secondary school is aimed at providing a more complete education as well as providing training for trade schools or university via electives. Although it takes inspiration from non-Loa countries for its educational system, it was designed by Loa nationalists to instill loyalty in Takatts Loa and to produce highly educated and specialized students to promote the growth of the nation during its post-colonial days. It also has roots in the Loafication era, with many aspects of the genocidal "rural education schools" being adapted to a national level. This has attracted particular criticism as being a relic of the past, efforts to completely replace it with a new system have largely faltered, but the education system has expanded its course catalog and altered its curriculum to be less nationalistic. | |||

Higher education in Takatta loa tends to consist of smaller private trade schools or colleges, but the majority of university and trade students attend Heauaka University in Disa'adakuo, which is the only state supported higher education facility. However, it is massive in scale and support with around 2.5 million students attending it and employing 90,000 professors and other educational faculty. There are around 400 private universities and trade schools with a combined 2.9 million students. | |||

===School Year=== | |||

The school year follows the Loa luni-ecdysial calendar, which measures time along both a lunar calendar and an "ecdysial" calendar that measures the silkworm seasons. There are 304 school days, with 41 holidays and 20 non holiday free days. The start of the school year is November 24th, which continues for the first ecdysial season until the 65th day until the 5 day long break at the end of the season. This continues until the fifth and last season, which is followed by the Loa 15 day New Years celebration. Other major holidays include the three Eid holidays celebrated by Loa Muslims, Eid al-Fitr, Eid al-Adha and Eid al-Gadhir, as well as the 12 lunar holidays, the 2 secular holidays of Peace Day and Constitution Day, and the four Loa religious holidays of Aiasin-sekkin, Huehuekaso-sekkin, Akaru'a-sekkin and Toua-sekkin. Takatta Loa organizes a school year based on a pentester, with the school year being divided into the five ecdysial cycles. | |||

This system applies to primary, secondary and higher education. Furthermore, primary and secondary mandate a seven hour school day with a two hour break in the middle, from noon to 9 pm. This means that on average, a Loa student would experience around 38,304 hours of school from grade 1 to grade 13. However, due to the fact that the lunar calendar is 11 days shorter than the ecdysial calendar, and that both the Muslim holidays and the lunar holidays fall on different days every year, the actual number tends to be larger due to the fact that inevitably some holidays will overlap, meaning that the Loa student can expect to have less than the expected 61 free days every few years. | |||

==Culture and Society== | ==Culture and Society== | ||

Revision as of 15:00, 14 August 2023

Republic of Takatta Loa Jomria'ari Takatta Loa (Insuo Loa) | |

|---|---|

|

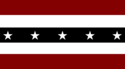

Flag | |

Motto: Nakui'i hikabisi nisuna kata nahaju mata'a (Insuo Loa) WIP | |

Anthem: Under the Banyan's Shade | |

| Capital | Ninao |

| Largest city | Disa'adakuo |

| Official languages | Insuo Loa |

| Ethnic groups (2030) |

|

| Religion | Kapuhenasa |

| Demonym(s) | Loa |

| Government | Constitutional Theocracy |

• Incarnate | Sedanraia, Incarnate of Natano |

| Legislature | Four Houses |

| Closed Houses of Queens and Orders | |

| Open Houses of Commons and Chieftains | |

| Establishment | |

• Settlement Period | 1700 BCE - 650 BCE |

| Area | |

• Total area | 658,763.476 km2 (254,350.000 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2030 census | 124,562,985 |

• Density | 190/km2 (492.1/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2030 estimate |

• Total | $4,675,285,076,245 |

• Per capita | $37,533.50 |

| Currency | Loa Luo (LLU) |

| Driving side | left |

Takatta Loa, officially known as the Republic of Takatta Loa, is a nation approximately 254,350 miles in area and located on the subcontinent Vallos, which is located on Sarpedon. Takatta Loa is predominantly wet, tropical rainforest, with a seasonal monsoon. The environment makes for an exceptionally biodiverse region, with many of the indigenous plants and animals being found only elsewhere on Vallos and nowhere else in the world. It shares a border with its northern neighbor of Almadaria.

Modern day Takatta Loa is a constitutional theocracy, with the Order of Natano being the official rulers of the republic, but holding mostly ceremonial powers and very limited legislative powers. The four legislative Houses, divided broadly into Open (elected officials) and Closed (hereditary or very limited electorate), hold the powers of government. In particular, the Open Houses are the primary legislative, administrative and security focused bodies while the Closed Houses form the national budget and oversee healthcare and education. All four of the legislative houses are involved in the legislative voting process, however.

The Empire of Takatta Loa was a rump state of the Kiravian proxy-colony of the same name, and was the direct predecessor of modern day Takatta Loa. Founded in 1699 and collapsing in 1875, the Empire at one point held all of southern Vallos before much of the colonial territory broke free following the death of Empress Tia'atiauela II, the second empress. Throughout the late 1700s and 1800s, the Empire underwent an intense process of "Loafication" wherein the mainland populations were forced to adopt Loa writing, language and culture. However, this period also resulted in significant religious development of the indigenous Kapuhenasa, which led to the development of organized and advanced entomantic orders. Modern Takatta Loa was officially founded in 1897 by Incarnate Toato Ani of the Order of Natano following the collapse of the Empire and the resulting Takatta Civil War. At the time, it was functionally an absolute theocracy with the Order regulating all aspects of life to conform to its political theology, and it also resulted in the freedom of Takatta Loa from Kiravian influence. Bolstered by sudden economic freedom, the Order sought to advance the economy beyond the previous plantations that served to enrich Kiravia. Although economic diversification was successful, significant political oppression resulted in the October Rebellion of 1952 which nearly overthrew the Order. After the death of Incarnate Ngatono in 1967, his successor Incarnate Sunuata began to negotiate with significant revolutionaries, royalty and the other influential entomantic orders. In 1970, the state was offically converted into the modern Republic of Takatta Loa and the Order of Natano relegated to largely ceremonial functions.

Takatta Loa boasts a diverse and still developing economic market. One of the largest industries in the nation is shipping, with Takatta Loa having some of the most robust shipping yards in the world. Further, agriculture still forms a significant portion of income, although it has been largely modernized. In particular, Takatta Loa is the largest producer of ginger and coconut in the world, bringing in around 1.5 and 26 billion taler respectively, and is a very significant producer of the cola used in Imperial Cola, as well as having the oldest bottling plant located outside of Paulastra. The nation also produces 84% of the world's supply of Copium, which is mostly exported to other countries with a marginal amount remaining in Takatta Loa. There is additionally a very large tourism industry in Takatta Loa, bringing in an estimated 50 billion taler a year. There is an especially large focus on Cartadania, with Cartadanians recieving free tourist visas and the travel company LoaMajeste aggressively lobbying and advertising in Cartadania for travel to Takatta Loa. Especially, the island of Jennasura has been developed specifically to attract tourist, to the detriment of the indigenous non-Loa polynesians. Currently, there is much development going into the production and research of pharmaceuticals, with Rehangi Pharmaceuticals being founded and based in Takatta Loa. However, not all economic advancement has been distributed evenly, with the region of Akanatoa receiving significantly less attention than others. This has resulted in a large drug and arms trade occurring out of Akanatoa. The Hoa'akalra Cartel in particular has demonstrated separatist tendencies, resulting in the Akanatoa War.

Etymology

History

Polynesian Settlement

The earliest definitive evidence of Polynesian habitation in Vallos dates back to around 1500 BCE, with remnants of distinctly Polynesian house posts being found on the island of Kakurana. The obscure indigenous people of Vallos left little evidence of their housing structures, leaving behind only pottery and arrowheads and axheads, so the emergence of Polynesian post holes in the archeological record is often used to track the advancement of Polynesian culture. As the ancient Polynesians advanced across southern Vallos, native Vallosi arrowheads and axe heads disappeared while Vallosi pottery styles remain and in some cases persist to this day, indicating that the cultural knowledge of indigenous Vallosi women survived in contrast to that of men. Although much of southern Vallos, especially along the rivers, practiced settled agriculture, examinations of middens show a significant amount of foraged game in the diet, suggesting a division of labor along gender lines with women farming and men hunting.

These historical developments align well with the "Vallosi Saga" theory, which states that the Polynesians were met with violence and repelled from Vallos, with later "invasions" of Polynesians supplanting the indigenous Vallosi. Both genetic testing and archeological evidence show that Vallosi women were often integrated and assimilated, with up to 60% of Loa having a significant Vallosi contribution to their mitochondrial DNA, in contrast to Vallosi men who left a very small genetic footprint. An exception is that of the Loa Islands, with many individuals having no Vallosi contribution. Archeological evidence suggests Kakurana and its neighboring islands were uninhabited, and that perhaps the voyages of the Saga theory took place between what would become the Loa Islands and the Vallosi mainland.

The above-mentioned "Vallosi Saga" project collected oral traditions from across Takatta Loa and southern Vallos and examined for examples of cultural continuity indicating potential historical value. The project led to the aforementioned conclusions of invasion, repellation and later return and supplantation. However, multiple differences were noted between the arrival stories of the Loa and Loa influenced cultures vs the non Loa stories, cementing some of the earliest examples of distinction between the Loa and other Polynesian groups. The typical arrival story tends to have a chieftain or chieftains who sets off on a voyage, often meeting mythological sea creatures along the way, until he arrives in Vallos. There, he encounters settled agriculture and in many stories integrates into a village typically through some great feat of heroism. However, eventually the chieftain and his crew are driven back into the sea where many of them die on the voyage back to the home islands. The chieftain swears vengeance and returns with an army to conquer the Vallosi. This aligns with the Saga theory and although names and details differ across traditions and cultures, this broad archetype remains the same. However, the Loa arrival story differs dramatically in that the Loa apparently are a later Polynesian arrival to Vallos. As such, they arrive on the island of Kakurana and encounter fellow Polynesians. Most notably, the Loa arrived under the guidance of a queen. Whether or not this is the origin of Loa pseudo-matriarchal society or whether Loa society later informed their own origin story is still the cause of much historical debate. Regardless, the Loa story concludes with the queen killing the native king after pretending to become his consort and supplanting his village. All Loa influenced cultures also tend to modify their own arrival stories, with the chieftain dying just after making it home and his queen setting off to avenge him. Experts tend to dismiss these stories as being directly influenced by the Loa and by 19th century attempts to enforce 'Loafication' on the mainland cultures, to evident success.

Polynesian Establishment

The period of Polynesian settlement lasted from 1500 to 500 BCE and generally ends with the last significant emergence of Polynesian archeological records in a region, which usually also entailed Polynesian supplantation of the native population. By the 5rd century BCE, wet rice agriculture had become standard across all riverine cultures, resulting in significant increase of Polynesian populations. Although there is no mention or evidence of cultivation of crops besides coconut, ginger and taro in the Polynesian records, the very quick adoption of wet rice agriculture indicates that the new invaders were familiar enough with agriculture to understand the value of rice, as well as the survival of Vallosi women's culture and work.

Polynesian began to diverge at this time into two very broad cultural distinctions, that of settled riverine agriculturalists and nomadic highland groups of either shifting agriculturalists or hunter gatherers. Both oral records and archeological evidence suggests that Polynesians waged significant warfare as their population moved into the highlands, likely from the last remnants of the southern Vallosi. One battle site yielded a total of 3,500 abandoned arrowheads, almost certainly from the same conflict, as well as large amounts of ash concentrated in one area, presumed to be a large Vallosi village. By 200 BCE, the last of the Vallosi are thought to have been supplanted, although small groups are known to have survived until the 1200s, though there remains no evidence of indigenous Vallosi survival. This also marks the beginning of the Polynesian Iron Age, thought to have originated via trade with the Occident.

The presumed reasons for this expansion into areas previously undesired by the new settlers are unclear though Loa scholars have reconstructed a theory of "Highland Transition"' based on riverine archeological sites in mainland Takatta Loa and examination of oral traditions. Evidence suggests that after settling into the lowlands and establishing wet rice agriculture, the Polynesians experienced an unprecedented population boom. The Transition theory suggests that these later Polynesians preserved a cultural response derived from island habitation of voyaging away to settle new lands. However, with Vallos being far larger than any island and with many of these populations being landlocked, the so called "voyagers" led expeditions to lands unsettled by the Polynesians, the highlands. However, the theory also suggests that these voyages were far less successful at establishing larger settlements and so many voyagers attempted to return home. Previous systems of agricultural management were unprepared to accommodate the large population, and so a widespread collapse of populations forced many to flee into the highlands due to famine or war. This incidentally resulted in a fulfilling of the settlement archetype laid out in oral traditions of centuries past, and potentially cementing the story tradition as a fundamental aspect of Polynesian culture even among landlocked groups that had never seen the sea.

Polynesian Iron Age

Lasting from about 200 BCE to 1000 CE, the Polynesian Iron Age is marked by significant growth and development of Polynesian culture including the establishment of large confederacies and literacy. By 200 CE, evidence of population recovery and successful establishment of highland Polynesians began to emerge. Further, oral traditions begin to gain more reliability and a more accurate picture of Polynesian life at this time can be constructed.

Urban culture advanced significantly during this time and in what would become Takatta Loa, three prominent cities emerged; Disadako, Arai'ia and Husnande (Husunanude in Old Insuo Loa). Each founded around 300 BCE, they were some of the largest economic centers in southern Vallos at the time. Nearly 70,000 people lived in Arai'ia at the time. Although no written records exist during this time, oral traditions record that each city tended to have around three to five kings who vied for power and control. Archeological excavations in the site of Arai'ia and in modern day Disa'adakuo have revealed palaces with many jade and turquoise regalia. These palatial cultures seem to have been the primary administrative centers of the city, but there were often many contemporaneous palaces in a single city, indicating perhaps joint rulership. In addition, separate palaces were associated with specific luxury goods, such as jade materials or a predominant focus on earrings. These have been used to define the extent of a palace’s influence as such artifacts are found in small shrine-like buildings elsewhere in a region, indicating perhaps an extension of the clan spirits and thus the palace’s power. They can also be used to define the length of time a particular palace ruled.

Palatial Kingdoms Era

The Palatial Era is an overlapping period with the Iron Age starting around roughly 400 CE and ending around 1000 CE. It is heavily associated with the rise of palace cultures and especially with multiple palaces within a city or region competing for power. This period also saw the rise of the first states in Takatta, that of the riverine mainland city states. All of these states arose prior to the development of writing and literacy in Takatta Loa, and two of the palatial states disappeared from the archeological record prior to the establishment of literacy. Aside from these palaces, referred to as Disa'adakuo P3 and Arai'ia P1, four palaces dominated the landscape of the Ahoso river basin; Aiaka in Disa'adakuo, Keikono in Arai'ia, Nagala in Husnande and Ranafaia in Disa'adakuo. It is unlikely that these are the actual names, as they are reconstructed from modern Loa readings of the characters used in their later times.

These palaces were, at any given time, six of a few dozen or so, and were simply the ones who exerted the most influence. Later writings confirm this, indicating that they received tribute from subordinate palaces. The income from the vassal palaces varied depending on region, but typically consisted of crops or slaves, as well as cowrie shells. Certain palaces, especially Aiaka from 750 CE to 830 CE, amassed such prestige and influence that goods from across the entirety of Takatta Loa, including feathers from the Loa Islands, have been found in the palatial tombs, which were built very far from the site of modern day Disa’adakuo. However, their control was marginal beyond receiving taxes and despite the large armies they often claimed to have, there is very little evidence of warfare during this time. Instead, palaces seemed to have risen and fallen into and from prominence organically as the families that constituted the palaces naturally grew into influence and disintegrated.

The control of the palaces rarely extended to the internal politics of any subordinate palaces, and this would end up being the reason for the collapse of the palatial cultures and the beginning of the Takatta Loa medieval age. From 700 to 900 CE, there were a series of incredible innovations that would lead to both the enrichment and development of mainland cultures, and the collapse of the palaces. The first major development was the genesis of the Loa scripts, which had since the 400s been slowly developing from pre-literate glyphs to a fully-fledged writing system. The speed of this development is remarkable but is generally assumed to have been influenced by the Latin script, as Caphiric artifacts have been found in the region around this time. However, the Loa scripts, tentatively called the Rongorongo scripts by emerging researchers, are thought to have not been derived from any occidental script but rather been a deliberate attempt to create a script from existing glyphs. One theory is that the palaces or one palaces in particular, created the script in order to control the language of trade in the region and prevent Caphiric scripts from taking root and potentially allowing power to shift into a merchant class. The fact that palaces would allow merchants to be educated in the (perhaps deliberately) convoluted logographic system for free suggests that this may be the case, as well as the bizarre and recurring phenomenon where the rulers of a palace boast in a stele or wall panel about how they “commanded the voice ... [and] bound the spirits [with it]”. This is thought to be a poetic interpretation of controlling trade through developing a system of keeping track of goods, as the Polynesians interpreted spirits as controlling fortunes.

Despite its potential outside influence, literacy became an extremely influential aspect of palatial society at the time, with people very quickly realizing its use in poetry and general communication. Spiritual aspects as seen above became associated with writing, and since the palaces controlled literacy, this allowed them extensive control over the religious landscape of their domains.

Geography

Ecology

Climate and environment

Government and Politics

Takatta Loa is a constitutional theocracy with a semi-bicameral legislature. The divine spirit Natano is the official head of state according to the constitution, although he speaks through his human representative in the mundane realm. This means that in practice, the Incarnate of the Order of Natano is the head of state, although they have largely ceremonial powers and little impact on government, with the powers of government lying in the Four Houses. The upper house is divided into the Houses of Orders and Queens, with 14 and 12 members respectively for a combined total of 26 members of the two upper houses. The lower house is divided into the Houses of Commons and Chieftains, with 500 legislators in each, for a combined total of 1,000 legislators. The upper and lower houses have divided legislative, taxation and budget setting duties, as well as divided duties for appointing the higher government officials. The actual administration of the government is done by the Ten Ministries system, whose High Ministers are elected from among and by the employees of the ministries and whose supporting cabinet of coordinators are appointed by the legislature. Government officials are selected via an internship and examination system, and are then typically promoted from within

Law

Demographics

Ethnicity

Self-reported ethnic group in Takatta Loa (2026)

Language

Religion

Education

Education in Takatta Loa is available in either public or religious schools, both of which follow the state mandated 13 year program, starting at age 5. Students go through 5 years of primary education followed by 8 years of secondary education and then students can choose whether to pursue a trade or higher education or neither. Classes for primary education in public schools include Mathematics, Literacy, Cultural studies, Physical Education and Secular Sciences. Secondary school includes more advanced studies of the above, as well as Takatta Loa History, World history, Religious studies and Loa cultural studies as mandated courses, with electives including such things as Music theory, Medicine, Muslim studies, Arabic language, Forestry, etc. Secondary school is aimed at providing a more complete education as well as providing training for trade schools or university via electives. Although it takes inspiration from non-Loa countries for its educational system, it was designed by Loa nationalists to instill loyalty in Takatts Loa and to produce highly educated and specialized students to promote the growth of the nation during its post-colonial days. It also has roots in the Loafication era, with many aspects of the genocidal "rural education schools" being adapted to a national level. This has attracted particular criticism as being a relic of the past, efforts to completely replace it with a new system have largely faltered, but the education system has expanded its course catalog and altered its curriculum to be less nationalistic.

Higher education in Takatta loa tends to consist of smaller private trade schools or colleges, but the majority of university and trade students attend Heauaka University in Disa'adakuo, which is the only state supported higher education facility. However, it is massive in scale and support with around 2.5 million students attending it and employing 90,000 professors and other educational faculty. There are around 400 private universities and trade schools with a combined 2.9 million students.

School Year

The school year follows the Loa luni-ecdysial calendar, which measures time along both a lunar calendar and an "ecdysial" calendar that measures the silkworm seasons. There are 304 school days, with 41 holidays and 20 non holiday free days. The start of the school year is November 24th, which continues for the first ecdysial season until the 65th day until the 5 day long break at the end of the season. This continues until the fifth and last season, which is followed by the Loa 15 day New Years celebration. Other major holidays include the three Eid holidays celebrated by Loa Muslims, Eid al-Fitr, Eid al-Adha and Eid al-Gadhir, as well as the 12 lunar holidays, the 2 secular holidays of Peace Day and Constitution Day, and the four Loa religious holidays of Aiasin-sekkin, Huehuekaso-sekkin, Akaru'a-sekkin and Toua-sekkin. Takatta Loa organizes a school year based on a pentester, with the school year being divided into the five ecdysial cycles.

This system applies to primary, secondary and higher education. Furthermore, primary and secondary mandate a seven hour school day with a two hour break in the middle, from noon to 9 pm. This means that on average, a Loa student would experience around 38,304 hours of school from grade 1 to grade 13. However, due to the fact that the lunar calendar is 11 days shorter than the ecdysial calendar, and that both the Muslim holidays and the lunar holidays fall on different days every year, the actual number tends to be larger due to the fact that inevitably some holidays will overlap, meaning that the Loa student can expect to have less than the expected 61 free days every few years.

Culture and Society

Attitudes and worldview

Kinship and family

Cuisine

Religion

Arts and Literature

Sports

Symbols

Economy and Infrastructure

Agriculture

Agricultural products constitute around 11% of Takatta Loa's GDP, and 4% of its workforce. Measuring the prevalence of agriculture as a means of economic activity is difficult due to the fact that cultivation is considered a moral good in Takatta Loa. As such, 53% of Loa report that they maintain a garden or pots of vegetables, with 90% of Loa reporting that they or somebody in their household cultivates plants. Further, 75% of those Loa report receiving profit from these crops, but the vast majority of these reports are ignored when discussing GDP, as they typically consist of selling excess fruit for very cheap prices to neighbors, or even for non monetary value that is still considered profit. As such, the Ministry of Agriculture estimates the above value to be the most accurate assessment.

Of the crops grown in Takatta Loa, spices are the largest profit sector with up to 40 percent of all agricultural exports being spices. Takatta Loa itself is a large consumer of spices with up to 30% of all spices produced in Takatta Loa being consumed domestically. With the exception of exotic Occidental spices like mint, thyme and bay leaves, Takatta Loa imports no spice products. It is estimated around 20% of cultivated land in Takatta Loa is dedicated to spices, with 40% being devoted to wet rice agro-forestry, 10% to coconut plantations, 5% to sugar cane and the other 20% to other crops. The variety of spices that are exported by Takatta Loa include ginger, nutmeg, mace, Copium seeds, white pepper, red pepper, chilis, cinnamon and cumin.

Coconut is the other main export of Takatta Loa, largely to Cartadania, Urcea and other Occidental countries, although there is a very large domestic demand for coconuts with 25% of all coconuts remaining in Takatta Loa. The Loa utilize coconut in most aspects of daily cuisine, and it has been named the national fruit for its significance in Loa culture and cuisine. An origin myth common among the Loa is that the rivers of Ahoso and the Masa were formed by everflowing celestial coconuts falling to the earth and cracking open in the mountains, hence why the waters of Takatta Loa are so sweet. It is extremely common to see coconut stands on the highways and in tram stations, with the trees growing wild in Takatta Loa and completely unrestricted to harvest. Even still, there are many coconut plantations in Takatta Loa, although due to the intense push for sustainable agriculture in the 2000s, many of these plantations also include other tree species that provide valuable crops. 26 billion taler is brought in from edible coconut products, and an additional 200 million from inedible coconut products.

Other prominent crops include sugar, cola for Imperial Cola, chocolate and seaweed. Sugar used to be the primary export of Takatta Loa in the 19th and 20th century but this has declined significantly since the 1940s due to general decline in interest and a political and social move to diversify agriculture and move past the colonial agriculture system. Since then, only around 12% of sugar produced in Takatta Loa is exported, with the rest remaining to feed the large domestic demand. Cola is almost never consumed in Takatta Loa, and is used exclusively for Imperial Cola, which is equally unpopular but with a few prominent bottling plants located inside the nation, Cola naturally is grown in order to limit import costs. Chocolate is also unpopular in Takatta Loa, and is largely farmed for export. Around 5 billion taler in chocolate beans are exported, while Takatta Loa manufactures and sells around 4 billion taler of processed chocolate, cocoa powder and cocoa butter. Seaweed is consumed largely domestically due to the weak international interest in Loa seaweed and the strong domestic interest. Around 1 billion taler in seaweed is consumed each year.