History of Pelaxia: Difference between revisions

| (37 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

The history of Pelaxia dates to the Antiquity when the pre-Caphirian peoples of the Kindred coast of the Pelaxian Valley made contact with the Kosalis and the first writing systems known as Paleopelaxian scripts were developed. In 1485, Jerónimo | The history of Pelaxia dates to the Antiquity when the pre-Caphirian peoples of the Kindred coast of the Pelaxian Valley made contact with the Kosalis and the first writing systems known as Paleopelaxian scripts were developed. In 1485, Jerónimo De Pardo, the Grand Duke of Agrila, unified Pelaxia as a dynastic union of disparate predecessor kingdoms vassals to Caphiria; its modern form of a republic was established in 1852. | ||

During this period, Pelaxia was involved in all major Sarpedonian Wars, including the Kindred Wars. Pelaxian power declined in the latter part of the 18th century. | After the completion of the Union of Alahuela and the creation of the Carto-Pelaxian Commonwealth, the Crown began to explore across the Kindred Sea, expanding into Vallos and marking the beginning of the Golden Age. Until the 1750s, Pardorian Pelaxia was the one of most powerful states in Sarpedon. During this period, Pelaxia was involved in all major Sarpedonian Wars, including the Kindred Wars. Carto-Pelaxian power declined in the latter part of the 18th century. | ||

In the early part of the 19th century, most of the former Pelaxian Empire overseas disintegrated. A tenuous balance between liberal and conservative forces was struck in the establishment of a republic in Pelaxia; this period began in 1852 and ended in 1922. Then came the dictatorship of General Benedicto Álvaro Camargo (1922-1932). His government inaugurated a period ruled by a militarist party, the Restauración Nacional Party, up until 1957. From 1922 the country experienced rapid economic growth in the 1940s and early 1950s. With the death of Federico Pedro Olmos in November 1956 Pelaxia returned to the Federal Republic. With a fresh Constitution voted in 1958. | In the early part of the 19th century, most of the former Pelaxian Empire overseas disintegrated. A tenuous balance between liberal and conservative forces was struck in the establishment of a republic in Pelaxia; this period began in 1852 and ended in 1922. Then came the dictatorship of General Benedicto Álvaro Camargo (1922-1932). His government inaugurated a period ruled by a militarist party, the Restauración Nacional Party, up until 1957. From 1922 the country experienced rapid economic growth in the 1940s and early 1950s. With the death of Federico Pedro Olmos in November 1956 Pelaxia returned to the Federal Republic. With a fresh Constitution voted in 1958. | ||

=Antiquity ( | =Antiquity (700 BC - 300 AD)= | ||

The Cognati (from Latin: Cognatus) were a set of people that Caphirian sources identified with that name in the wester coast of Sarpedon over the Kindred Sea, at least from the 6th century BC. The Caphirian sources also use the term Pelagi to refer to the Cognati. The term Cognati, as used by the ancient authors, had two distinct meanings. One, more general, referred to all the populations of the cognatish valley without regard to ethnic differences. The other, more restricted ethnic sense, refers to the people living in the western and southern coasts of the Cognatish Valley, which by the 6th century BC had absorbed cultural influences from Vallos. This pre-Caphiravian cultural group spoke the Cognatish language from the 7th to the 1st century BC. Cognati society was divided into different classes, including kings or chieftains (Latin: "regulus"), nobles, priests, artisans and slaves. Cognati aristocracy, often called a "senate" by the ancient sources, met in a council of nobles. Kings or chieftains would maintain their forces through a system of obligation or vassalage that the Caphirians termed "fides".The Cognati adopted wine and olives from the Vallosi. Horse breeding was particularly important to the Cognati and their nobility. Mining was also very important for their economy, especially the silver mines, the iron mines in the Montian valleys, as well as the exploitation of tin and copper deposits. They produced fine metalwork and high quality iron weapons such as the falcata. | The Cognati (from Latin: Cognatus) were a set of people that Caphirian sources identified with that name in the wester coast of Sarpedon over the Kindred Sea, at least from the 6th century BC. The Caphirian sources also use the term Pelagi to refer to the Cognati. The term Cognati, as used by the ancient authors, had two distinct meanings. One, more general, referred to all the populations of the cognatish valley without regard to ethnic differences. The other, more restricted ethnic sense, refers to the people living in the western and southern coasts of the Cognatish Valley, which by the 6th century BC had absorbed cultural influences from Vallos. This pre-Caphiravian cultural group spoke the Cognatish language from the 7th to the 1st century BC. Cognati society was divided into different classes, including kings or chieftains (Latin: "regulus"), nobles, priests, artisans and slaves. Cognati aristocracy, often called a "senate" by the ancient sources, met in a council of nobles. Kings or chieftains would maintain their forces through a system of obligation or vassalage that the Caphirians termed "fides".The Cognati adopted wine and olives from the Vallosi. Horse breeding was particularly important to the Cognati and their nobility. Mining was also very important for their economy, especially the silver mines, the iron mines in the Montian valleys, as well as the exploitation of tin and copper deposits. They produced fine metalwork and high quality iron weapons such as the falcata. | ||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

Detalle de una reconstrucción de inscripciones celtíberas.jpg|Reconstruction of Cognati scripture | Detalle de una reconstrucción de inscripciones celtíberas.jpg|Reconstruction of Cognati scripture | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

Due to their military qualities, as of the | Due to their military qualities, as of the 4th century AD Cognatish soldiers were frequently deployed in battles in Caphiria. | ||

==Caphirian Pelaxia== | ==Caphirian Pelaxia== | ||

[[File:Roman bridge at night - Córdoba, Spain - DSC07251.JPG|thumb|Caphirian bridge at night in Soratia]] | [[File:Roman bridge at night - Córdoba, Spain - DSC07251.JPG|thumb|Caphirian bridge at night in Soratia]] | ||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

[[File:Eurico, rey de los Visigodos (Museo del Prado).jpg|thumb|right|Evaristo, King of the Kosali|303x303px]] | [[File:Eurico, rey de los Visigodos (Museo del Prado).jpg|thumb|right|Evaristo, King of the Kosali|303x303px]] | ||

===Caphirian recession and Kosal expansion=== | ===Caphirian recession and Kosal expansion=== | ||

In the mid 5th Century | In the mid 5th Century AD., the Caphirian Republic would eventually face internal pressure from ambitious leaders such as Luccino Capontinus and Iscallio Maristo, as contention for leadership caused a number of small fights among the ambitious youth and the elder aristocracy. The fighting would culminate with a five year civil war, known now as the War of the Republic, that left 120,000 people dead. The war was in such a frenzy that by the time it had ended, there was no decisive victor and as a consequence, the Republic was on the verge of total collapse. | ||

The undoing of Caphiravian control in the region was the result of four sarpedonian tribes crossing the Cazuano river in 407. After three years of depredation and wandering about southern Pelaxia the Losa, Ladri and Klis moved into Pelaxia in September or October 409. Thus began the history of the end of Caphiravian Pelaxia which came in 472. The Losa established a kingdom in Monti in what is today modern Montia and northern East Pelaxia. The Ladri also established a kingdom in the southern part of the region. The Klis established a kingdom in Albalitore – modern northwest coast. The Caphirian attempt under General Petia to dislodge the Septri from Jojoba failed in 422. Caphiria made attempts to restore control in 446 and 458 with partial success. | The undoing of Caphiravian control in the region was the result of four sarpedonian tribes crossing the Cazuano river in 407. After three years of depredation and wandering about southern Pelaxia the Losa, Ladri and Klis moved into Pelaxia in September or October 409. Thus began the history of the end of Caphiravian Pelaxia which came in 472. The Losa established a kingdom in Monti in what is today modern Montia and northern East Pelaxia. The Ladri also established a kingdom in the southern part of the region. The Klis established a kingdom in Albalitore – modern northwest coast. The Caphirian attempt under General Petia to dislodge the Septri from Jojoba failed in 422. Caphiria made attempts to restore control in 446 and 458 with partial success. | ||

In 484 the Kosal established Agrila as the capital of their kingdom. Successive Kosal kings ruled Agrila as patricians who held imperial commissions to govern in the name of the Caphirian Consul. In 585 the Kosal conquered the Losa Kingdom of Montia, and thus controlled a third of Pelaxia. | In 484 the Kosal established Agrila as the capital of their kingdom. Successive Kosal kings ruled Agrila as patricians who held imperial commissions to govern in the name of the Caphirian Consul. In 585 the Kosal conquered the Losa Kingdom of Montia, and thus controlled a third of Pelaxia. | ||

[[File:El_rey_Don_Pelayo_en_Covadonga_(Museo_del_Prado).jpg|thumb|Columbio, from a 12th-century [[illustrated manuscript]]|left| | [[File:El_rey_Don_Pelayo_en_Covadonga_(Museo_del_Prado).jpg|thumb|Columbio, from a 12th-century [[illustrated manuscript]]|left|384x384px]] | ||

=====Kingdom of Agrila===== | =====Kingdom of Agrila===== | ||

The Agrila Kingdom (Latin: Regnum Agrili) was a kingdom that occupied what is now western Pelaxia from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the successor states to the Caphiravian presence in the Province, it was originally created by the settlement of the Kosali under King Magda in Agrila.The Kingdom maintained independence from the Caphiravian Empire, whose attempts to re-establish authority in Pelaxia were only partially successful. Under King Evaristo - who eliminated the status of imperial commissions - a triumphal advance of the Kosali began. Alarmed at Kosali expansion from Ficetia after victory over the Caphirian armies at Cakia in 479, the Consul sent a fresh army against Evaristo. The Caphirian army was crushed in battle nearby and Evaristo then captured Soratia and secured all of Pelaxian Valley. | The Agrila Kingdom (Latin: Regnum Agrili) was a kingdom that occupied what is now western Pelaxia from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the successor states to the Caphiravian presence in the Province, it was originally created by the settlement of the Kosali under King Magda in Agrila.The Kingdom maintained independence from the Caphiravian Empire, whose attempts to re-establish authority in Pelaxia were only partially successful. Under King Evaristo - who eliminated the status of imperial commissions - a triumphal advance of the Kosali began. Alarmed at Kosali expansion from Ficetia after victory over the Caphirian armies at Cakia in 479, the Consul sent a fresh army against Evaristo. The Caphirian army was crushed in battle nearby and Evaristo then captured Soratia and secured all of Pelaxian Valley. | ||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

=Caphirian Reconquest (500 to 1485)= | =Caphirian Reconquest (500 to 1485)= | ||

==Middle Ages - Pelaxia under Castrillón rule== | |||

=== | |||

Under the Catholic Kosali nobles, the feudal system proliferated, and monasteries and bishoprics were important bases for maintaining the rule. The Kosali were caphirianized Southern Sarpedonians and were to keep the “Caphiravian order” against the hordes of Ladri, Rati, Losa and Rastri. The | ===Sebastián Pasillas of Castrillón, Despote of Cognata=== | ||

The rise of the | |||

Under the | Under the Catholic Kosali nobles, the feudal system proliferated, and monasteries and bishoprics were important bases for maintaining the rule. The Kosali were caphirianized Southern Sarpedonians and were to keep the “Caphiravian order” against the hordes of Ladri, Rati, Losa and Rastri. | ||

While some of the "Free Communities" (Comunidades Libres, i.e. Montia, Cevedo, and Bajofort) were Imperolibertos the | |||

In the year 1175, Sebastián received a summons that would rekindle the flames of his political destiny. The Republic, recognizing his potential and understanding the gravity of the situation in the Pelaxian valley, tasked Sebastián with the "Pacification of Cognata." The Kazofort Rebellion, an epochal struggle for independence from Caphirian dominion, was spearheaded by a fiercely determined leader named Hernán de Kazofort. Hailing from a lineage of Kosali families, Hernán was a man of towering stature and indomitable will. | |||

The seeds of rebellion were sown in the Pelaxian valley as a palpable discontent simmered among the indigenous warlords and noble families. Tensions came to a head when Hernán Kazofort, with his fiery oratory and impassioned rallying cries, galvanized the warlords, known as "Las Familias del Valle" or "The Valley Families," to unite under a common banner. The primary grievance of The Valley Families was the burden of incessant tributes demanded by Venceia, the imperial capital, and the relentless conscription of their sons into the Caphirian legions. Kazofort’s eloquence resonated deeply with the warlords, who had long harbored resentment toward their Caphirian overlords. | |||

In a pivotal moment, during a clandestine council at the Kazofort Estate, the lord of the castle brandishing a tattered standard bearing the emblem of a free Pelaxia, declared the cessation of tribute payments to Venceia and the refusal to send their sons to fight in distant wars for the Caphirian Empire. His call to arms ignited a fervor among The Valley Families, and they rallied behind their newfound leader. | |||

Pasillas, arrived in the Pelaxian valley with a modest retinue of loyal soldiers. His initial attempts to establish a foothold were met with fierce resistance from the local lords, notably the formidable Kazofort family. | |||

As the rebellion gained momentum, Caphiria responded with ruthless determination, dispatching legions under the command of Pasillas to quell the insurrection. What ensued was a series of skirmishes and battles across the Pelaxian valley, each marked by Hernán de Kazofort’s astute military leadership and the unwavering resolve of the Valley Families. | |||

But in 953, at the climactic Battle of Torrent's End, Hernán de Kazofort met his fate in the heat of combat, valiantly leading his troops against overwhelming Caphirian forces. His sacrifice, however, would not be in vain. His legacy lived on in the hearts of the Valley Families, who continued to wage a relentless struggle for their freedom. | |||

Ultimately, the Kazofort Rebellion exacted a heavy toll onThe Valley Families were specially decimated by Pasillas. Although the end of the rebellion meant the ascendancy of a new Caphiravian despote ruling the valley with autonomy, the rebellion's indomitable spirit would serve as an enduring symbol of Pelaxian resilience in the face of external domination. The legacy of Hernán and the Valley Families would echo through the annals of Pelaxian history, serving as a poignant reminder of the enduring quest for liberty and self-determination. | |||

After years of relentless campaigning and painstaking negotiations, Pasillas succeeded in restoring order to the tumultuous region of Cognata. His crowning achievement was the "Edict of Agrila," issued in 1180, which formally designated him as the Despote of Cognata and moved his royal seat to Albalitor. This historic decree signaled a turning point in the history of both Caphiria and Pelaxia, solidifying Pasillas's legacy as a statesman and military strategist of unparalleled repute. The Edict of Agrila effectively assigned the western part of modern Pelaxia to the House of Castrillón, ruled by Sebastián Pasillas, Despote of Cognata, and the eastern part to the eastern part to its vassal Duke of Agrila. The Castrillón dynasty's 12th-century rise led to the establishment of cities like Alimoche, Fatides, and Barcegas. Concurrently, the Castrillóns expanded their influence, absorbing southern territories and forming alliances. The Montian Confederacy emerged as a political entity during this time, uniting various provinces under its banner. The 14th century witnessed a shift from feudalism to late medieval politics, with the Castrillóns vying against Agrila and Sebardoba for control. Battles and alliances reshaped the geopolitical landscape. In 1469, Despotes Mauhtémoc Castrillón's involvement in the Termia region led to conflicts, including pivotal battles like Alcoy and Jumilla. The fall of [[Tristán Castrillón]] in 1477, in which the [[Montian Confederacy]] played a role, marked a turning point, signaling the decline of the Castrillón dynasty and the realignment of power dynamics in the region. | |||

Apart from the recognition he must feel towards him, The Republic probably also saw in the appointment of Pasillas, heir to the Castrillóns but also attached to the Pelaxian valley, a factor of stability which could rid the imperial administration of the management of a territory with endemic troubles. | |||

===Comunidades Libres=== | |||

The rise of the Castrillón dynasty gained momentum when their main local competitor, the Kazofort dynasty, died out and they could thus bring much of the territory south of the Rayado River under their control. Subsequently, they managed within only a few generations to extend their influence through Savria in south-eastern regions. | |||

Under the Trasfluminan rule, the Picos passes in Montia and the San Alberto Pass gained importance. Especially the latter became an important direct route through the mountains. The construction of the "Devil’s Bridge" (Puente del Diablo) across the Picos Centrales in 1198 led to a marked increase in traffic on the mule track over the pass. | |||

While some of the "Free Communities" (Comunidades Libres, i.e. Montia, Cevedo, and Bajofort) were Imperolibertos the Castrillón still claimed authority over some villages and much of the surrounding land. While Cevedo was Imperoliberti in 1240, the castle of Nueva Brine was built in 1244 to help control Lake Lucrecia and restrict the neighboring Forest Communities. In 1273 the rights to the Comunidades were sold by a cadet branch of the Castrillón's to the head of the family, Laín II. Laín II was therefore the ruler of all the Imperoliberti communities as well as the lands that he ruled as a Castrillón. | |||

Laín II instituted a strict rule in his homelands and raised the taxes tremendously to finance wars and further territorial acquisitions. As king, he finally had also become the direct liege lord of the Comunidades Libres, which thus saw their previous independence curtailed. On the April 16, 1291 Laín bought all the rights over the town of Lucrecia and the abbey estates in Bajofort from Abbey. The Comunidades saw their trade route over Lake Lucrecia cut off and feared losing their independence. When Laín died on July 15, 1291 the Comunidades prepared to defend themselves. On August 1, 1291 a League was made between the Comunidades Libres for mutual defense against a common enemy. | Laín II instituted a strict rule in his homelands and raised the taxes tremendously to finance wars and further territorial acquisitions. As king, he finally had also become the direct liege lord of the Comunidades Libres, which thus saw their previous independence curtailed. On the April 16, 1291 Laín bought all the rights over the town of Lucrecia and the abbey estates in Bajofort from Abbey. The Comunidades saw their trade route over Lake Lucrecia cut off and feared losing their independence. When Laín died on July 15, 1291 the Comunidades prepared to defend themselves. On August 1, 1291 a League was made between the Comunidades Libres for mutual defense against a common enemy. | ||

===The | |||

With the opening of the Gastian Pass in the | ===The Montian Confederacy=== | ||

The 14th century in the territory of modern Pelaxia was a time of transition from the old feudal order administrated by regional families of lower nobility (such as the houses of Babafort, Estreniche, Fegona, Fatides, Foronafort, Gouganaca, Huega, Tolefe, Terrafort, Rimiranol, Tarabefort, Santialche etc.) and the development of the powers of the late medieval period, primarily the first stage of the meteoric rise of the House of | With the opening of the Gastian Pass in the 14th century, the territory of Central Pelaxia, primarily the valleys of Montia, had gained great strategical importance and was granted Imperoliberti by the Trasflumina family of Agrila. This became the nucleus of the Montian Confederacy, which during the 1330s to 1350s grew to incorporate its core of "eleven shires" | ||

The 14th century in the territory of modern Pelaxia was a time of transition from the old feudal order administrated by regional families of lower nobility (such as the houses of Babafort, Estreniche, Fegona, Fatides, Foronafort, Gouganaca, Huega, Tolefe, Terrafort, Rimiranol, Tarabefort, Santialche etc.) and the development of the powers of the late medieval period, primarily the first stage of the meteoric rise of the House of Castrillón, which was confronted with rivals in Agrila and Sebardoba. The free imperial cities, prince-bishoprics and monasteries were forced to look for allies in this unstable climate, and entered a series of pacts. Thus, the multi-polar order of the feudalism of the High Middle Ages, while still visible in documents of the first half of the 14th century such as the Codex Manesse or the Montia armorial gradually gave way to the politics of the Late Middle Ages, with the Montian Confederacy wedged between Castrillón Pelaxia, the Archduchy of Agrila, the Duchy of Sebardoba and the Duchy of Ficetia. Babafort had taken an unfortunate stand against Castrillón in the battle of Scafaleno in 1289, but recovered enough to confront Fatides and then to inflict a decisive defeat on a coalition force of Castrillón, Sebardoba and Abubilla in the battle of Lupita in 1339. At the same time, Castrillón attempted to gain influence over the cities of Lucrecia and Zaralava, with riots or attempted coups reported for the years 1343 and 1350 respectively. This situation led the cities of Lucrecia, Zaralva and Babafort to attach themselves to the Montian Confederacy in 1332, 1351, and 1353 respectively. | |||

The catastrophic 1356 Abubilla earthquake which devastated a wide region, and the city of Abubilla was destroyed almost completely in the ensuing fire. | The catastrophic 1356 Abubilla earthquake which devastated a wide region, and the city of Abubilla was destroyed almost completely in the ensuing fire. | ||

The balance of power remained precarious during the 1350s to 1380s, with | The balance of power remained precarious during the 1350s to 1380s, with Castrillón trying to regain lost influence; Alberto II besieged Zaralva unsuccessfully, but imposed an unfavourable peace on the city in the treaty of Reifort. In 1375, Castrillón tried to regain control over the Savria with the help of Caphiric mercenaries. After a number of minor clashes, it was with the decisive Confederated victory at the battle of Campes in 1386 that this situation was resolved. Castrillón moved its focus westward and lost all possessions in its ancestral territory with the Confederated annexation of Brine in 1416, from which time the Montian Confederacy stood for the first time as a political entity controlling a contiguous territory. | ||

Meanwhile, in Abubilla, the citizenry was also divided into a pro-Castro and an anti-Castro faction. | Meanwhile, in Abubilla, the citizenry was also divided into a pro-Castro and an anti-Castro faction. | ||

===Termian Wars=== | |||

Initially in 1469, | ===First Termian Wars=== | ||

In a second phase, | Initially in 1469, Consul Mauhtémoc Castrillón of Albalitor assigned his possessions in the Termia as a fiefdom to the Duke of Barakaldo, Tristán, to have them protected better against the expansion of the Montian Confederacy. Tristán's involvement west of the Confederacy gave him no reason to attack the confederates as Mauhtémoc had wanted, but his embargo politics against several confederate communes, directed by his reeve Pedro de Goito, prompted these to turn to Agrila for help. Tristán's expansionist strategy suffered a first setback in his politics when his attack on the Archbishopric of Cuenca failed after the unsuccessful Siege of Gandía (1474–75). | ||

=Great Kingdom of Pelaxia ( | In a second phase, Mauhtémoc sought to achieve a peace agreement with the Montian confederates, which eventually was concluded in Agrila in 1474. He wanted to buy back his Termia possessions from Tristán, which the latter refused. Shortly afterwards, de Goito was captured and executed by decapitation in Termia, and the Monts, united with the Termia cities and Mauhtémoc of Castrillón in an "anti-Barakaldo league", conquered part of the Barakaldian land when they won the Battle of Alcoy in November 1474. The next year, Agrilan forces conquered and ravaged Vadia, which belonged to the Duchy of Savria, who was allied with Tristán. In 1476 Tristán retaliated and marched to Jumilla, which belonged to Didac of Savria, but which had recently been taken by the Confederates, where he had the garrison hanged or drowned in the lake despite their capitulation. When the Montian confederate forces arrived a few days later, he was defeated in the Battle of Jumilla, and he was forced to flee the battlefield, leaving behind his artillery and many provisions and valuables. Having rallied his army, he was dealt a devastating blow by the confederates in the Battle of Monforte. Tristán raised a new army, but fell in the Battle of Funes in | ||

1477, where the Confederates fought alongside an army of Prince Reginaldo of Baja Litoria. | |||

=Great Caphiravian Kingdom of Pelaxia (1485 to 1618)= | |||

[[File:Michel Sittow 004.jpg|thumb|356x356px|Jerónimo I of Pelaxia "the Edifier"]] | |||

====Background==== | ====Background==== | ||

====Beginning==== | ====Beginning==== | ||

=====King Jerónimo I===== | =====King Jerónimo I===== | ||

In 1485, the Union of Termia was signed between Reginaldo Castrillón of Alabalitoria and Jerónimo De Pardo, the Grand Duke of Agrila, the Head Chancellor of the Montian Confederacy. The act arranged for Reignaldo's daughter Josefina to marry Jerónimo, which established the beginning of the Pelaxian Kingdom and set the De Pardo's as the ''de facto'' Consuls of the province. The union strengthened both regions as self appointed protectors of Pelaxia, in their shared opposition to the newly formed Kingdom of Savria under King Didac l, self-appointed protector of the south. | |||

In 1485, the Union of Termia was signed between Reginaldo | |||

The intention of the union was to create a common state under Albalitorian law, with the support of the ruling oligarchy in the Montian Confederacy. | The intention of the union was to create a common state under Albalitorian law, with the support of the ruling oligarchy in the Montian Confederacy. Castrillón would gain access to the trade passes through the Picos into the Dominate of Caphiria, while the Confederates would gain access to Albalitorian ports and sea routes. Thus, in the Jeronimian period, Pelaxia developed as a feudal state with a predominantly agricultural economy and an increasingly dominant mercantile nobility. The Cortes Regium act adopted by Jerónimo established the Corte General in 1516 and in 1705 transferred most of the legislative power in the state from the monarch to the Corte. This event marked the beginning of the period known as "Golden Liberty", when the state was ruled by the "free and equal" members of the Pelaxian aristocracy and nobility. | ||

Between 1686 and | |||

Between 1686 and 1802, Pelaxia was ruled by a succession of constitutional monarchs of the Jeronimian dynasty of House De Pardo. The political influence of the Jeronimian kings gradually diminished during this period, while the landed nobility took over an ever-increasing role in central government and national affairs. The royal dynasty, however, had a stabilizing effect on Pelaxia’s politics. The Jeronimian Era is often regarded as a period of maximum political power, great prosperity, and in its later stage, a Golden Age of Pelaxian culture. | |||

=====Agriculture-based economic expansion===== | =====Agriculture-based economic expansion===== | ||

A large-scale system of agricultural production based on serfdom, was a dominant feature on Pelaxia’'s economic landscape beginning in the late 15th century and for the next 300 years. This dependence on nobility-controlled agriculture in Pelaxia diverged from Levantia, where elements of capitalism and industrialization were developing to a much greater extent, with the attendant growth of a bourgeoisie class and its political influence. The 16th-century agricultural trade boom combined with free or very cheap peasant labor made the folwark economy very profitable. | A large-scale system of agricultural production based on serfdom, was a dominant feature on Pelaxia’'s economic landscape beginning in the late 15th century and for the next 300 years. This dependence on nobility-controlled agriculture in Pelaxia diverged from Levantia, where elements of capitalism and industrialization were developing to a much greater extent, with the attendant growth of a bourgeoisie class and its political influence. The 16th-century agricultural trade boom combined with free or very cheap peasant labor made the folwark economy very profitable. | ||

Mining and metallurgy developed further during the 16th century, and technical progress took place in various commercial applications. Great quantities of exported agricultural and forest products floated down the rivers to be transported through ports and land routes. This resulted in a positive trade balance for Pelaxia throughout the 16th century. Imports from the East included industrial products, luxury products and fabrics. | Mining and metallurgy developed further during the 16th century, and technical progress took place in various commercial applications. Great quantities of exported agricultural and forest products floated down the rivers to be transported through ports and land routes. This resulted in a positive trade balance for Pelaxia throughout the 16th century. Imports from the East included industrial products, luxury products and fabrics. | ||

Most of the exported grain left Pelaxia through Albalitor, which quickly became the wealthiest, most highly developed, and most autonomous of the Pelaxian cities because of its location at the mouth of the Elodia River and access to the Kindred Sea. It was also by far the largest center for manufacturing. Other towns were negatively affected by Albalitor's near-monopoly in foreign trade, but profitably participated in transit and export activities. The largest of those were Agrila,Montia,Fegona, Fatides, Foronafort, Gouganaca, Huega, Tolefe, Terrafort, Rimiranol, Tarabefort, Santialche. | Most of the exported grain left Pelaxia through Albalitor, which quickly became the wealthiest, most highly developed, and most autonomous of the Pelaxian cities because of its location at the mouth of the Elodia River and access to the Kindred Sea. It was also by far the largest center for manufacturing. Other towns were negatively affected by Albalitor's near-monopoly in foreign trade, but profitably participated in transit and export activities. The largest of those were Agrila,Montia,Fegona, Fatides, Foronafort, Gouganaca, Huega, Tolefe, Terrafort, Rimiranol, Tarabefort, Santialche. | ||

=====Overseas expansion to Alshar and the route to Alshar===== | |||

==== | See also: [[Pelaxian discovery of the sea route to Alshar]] | ||

The Pelaxian discovery of the sea route to Alshar was the first recorded trip directly from Sarpedon to the Alshari continent, via the Freda Islands and the Zhijun Islands. Under the command of Pelaxian explorer Gabo de Pogiano, it was undertaken during the reign of King Jerónimo I and Consul Sebastián Pasillas of Castrillón. Considered one of the most remarkable voyages of the Carto-Pelaxian golden age, it initiated the Carto-Pelaxian maritime trade with the Daxian Qian dinasty and other parts of Alshar, the military presence and settlements of the Pelaxian in Tanhai. | |||

Gabo de Pogiano's 1615 journey became an embassy after contact with the Daxians. After arriving in the port of Zong on the 10th of October, he had an audience with Digen Youdu, Viceroy of Ganshu; with whom he negotiated an agreement that allowed him to dock in Daxian ports and engage in trade, map out the surrounding seas. Pogiano in turn committed himself to on his return trip, guide a Qian squadron to the Kindreds Sea and the coast of Sarpedon. The ships that would join him on Zhijun were the Falun, the Gong and the Shen Yun; the first Daxian ships to ever make it to Sarpedon. Later contacts with Acirien representatives would lead to a similar agreement. The Qian would send goods such as slaves, bolts of silk, sugarcane, barrels of slozo, pink salt, ebony wood, cinnamon and other spices and in return would receive olives, oil, wine, cattle and fruits. | |||

Pogiano sailing around Australis. | |||

=====Second Termian Wars (1620-1627)===== | |||

See also:[[Second Termian War]] | |||

The military conflict known as the Second Termian Wars (1620-1627) was a pivotal episode in the Wars of Independence between the Kingdom of Pelaxia and Caphiria. At its core, the war was ignited by Caphiria's aggressive endeavor to regain control over the Province of Pelaxia, which had recently rejected its vassalage. Moreover, the control of the Kindred Sea, a vital maritime route, was a central stake in this high-stakes geopolitical struggle. The contested territory of Termia, characterized by its treacherous marshes and meandering rivers, held profound strategic significance as it controlled access to both the Kindred Sea and the vital Province of Cartadania.The war unfolded as a gritty and protracted struggle, with limited use of firearms and a reliance on traditional tactics and disciplined formations. | |||

At the heart of the conflict was the newly formed professional army of Pelaxia, known as the "Las Huestes Reales". This force showcased its prowess in disciplined warfare, particularly with their utilization of heavy pikemen and the maneuvering expertise of "Rodeleros" ("Sword and Buckler Men") in the challenging swamp terrain. These tactics proved essential for navigating the challenging environment, where quicksand, dense foliage, and treacherous waterways demanded a unique approach. The clashes were marked by the grinding nature of swamp warfare, characterized by mud-soaked battles and grueling marches. The conflict gained a reputation for its gruesome nature, where soldiers contended not only with the enemy but also with the inhospitable environment. Firearm usage was limited, intensifying the reliance on close-quarter combat and skillful coordination of both big military formations and also more attritional tactits and lighter units. | |||

The culmination of the conflict was the Treaty of Broda, signed in 1627. The treaty marked a turning point in Pelaxia's struggle for independence, cementing its status as an independent kingdom. The terms of the treaty awarded Pelaxia partial control over the Termian Delta and its intricate network of rivers. This concession granted the kingdom a strategic foothold, solidifying its control over a critical access point to the Kindred Sea and the prized Province of Cartadania. | |||

In conclusion, the Second Termian Wars emerged as a crucial theater in the Wars of Independence, underscoring the resilience and strategic acumen of the Kingdom of Pelaxia. Against the backdrop of marshy battlegrounds and limited firearm usage, the conflict demonstrated the kingdom's disciplined warfare and culminated in the Treaty of Broda, securing its independence and strategic territorial gains. | |||

=Union of Alahuela and the Carto-Pelaxian Commonwealth (1632 - 1795)= | |||

See also: [[Carto-Pelaxian Commonwealth]] | |||

The Commonwealth was established by the Union of Alahuela in July 1632, carried by the major lords of Cartadanian and Pelaxian valleys, following the the Great Schism of 1615, where a break of communion between what are now the Catholic Church and the Imperial Church of Caphiria occurred and the invasion of Cartadania by the Grand Royal Army of Pelaxia. The Great Schism lead to the independence of the southern province of Pelaxia and the independence of the at the time vassal lords. The First Partition in 1772 and the Second Partition in 1793 greatly reduced the state's size and the Commonwealth was partitioned out of existence due to the Third Partition in 1795. | |||

The Union possessed many features unique among contemporary states. Its political system was characterized by strict checks upon monarchical power. These checks were enacted by a legislature (Concilii Regii) controlled by the nobility (Nobles). This idiosyncratic system was a precursor to modern concepts of democracy, as of 1791 constitutional monarchy, and federation. Although the two component states of the Commonwealth were formally equal, Pelaxia was the dominant partner in the union. | |||

The Carto-Pelaxian Commonwealth was marked by high levels of ethnic diversity and by relative religious tolerance, guaranteed by the Albalitor Confederation Act 1673; however, the degree of religious freedom varied over time. The Constitution of 1791 acknowledged Catholic Church as the "dominant religion", but freedom of religion was still granted with it. | |||

===Concili Regii=== | |||

===Coffee Wars=== | |||

===Savrian Wars(1708–1716)=== | |||

Carlos II became Emperor upon the death of Jerónimo lV on 18 October 1706. He was extremely concerned about the territorial expansion of the Kingdom of Savria in southern Pelaxia and its control over the Cazuano River which irrigated much of the central agricultural areas. | |||

In 1708 the circumstances were set for Carlos ll to invade Savria. Although the Great Pelaxian Army destroyed much of the Savrian forces at the Battle of Sogas on May 14, 1709, it failed to capture Leg. | |||

Carlos ll mounted another in 1710 but was defeated at the Battle of Casadevall on June 6, 1713. The Battle of Casadevall would be the last in which the traditional Pelaxian tactic of charging in three columns would be used. | |||

On January 1, 1715 Carlos died and was succeeded to the throne of Pelaxia by his nephew, Francisco I. Francisco I continued Carlos' war against the Savrian’s by leading an army against them at Sarua on September 13–14, 1715. This victory decisively broke the string of victories that the Savrians had enjoyed against the Pelaxians. Following the Battle of Sarua, Savrian crown collapsed. By the treaties of Nollola on August 13, 1716, and Albalitor, the entirety of southern Pelaxia was surrendered to the House of De Pardo. | |||

=====Levantamiento de Azul===== | =====Levantamiento de Azul===== | ||

=====Reacción===== | =====Reacción===== | ||

===== | =====Emperor Efraín I===== | ||

=First Republic (1804-1814): The Overthrow of the Monarchy and the Triumvirate= | |||

The historic period of the First Republic (1804-1814) marked a pivotal juncture in Pelaxian history, characterized by the dramatic overthrow of the monarchy, the instability of the Girojón dynasty, and the subsequent establishment of a triumvirate governance structure that endured for a decade. This transformative period was shaped by a convergence of military and civilian forces, driven by republican-oriented ideologies and a fervent commitment to redefining Pelaxia's political landscape. The Girojón monarchy, which had assumed the throne amidst the tumultuous socio-political environment of the late 18th century follwing the Third Partition of the Carto-Pelaxian Commonwealth, faced growing discontent among its subjects due to perceived authoritarianism and economic disparities. The culmination of public dissatisfaction and a burgeoning revolutionary sentiment led to a coordinated coup in 1804, orchestrated by a coalition of military leaders and civilian republicanist intellectuals. This coup saw the expulsion of the monarchy and the Girojón dynasty, altering the course of Pelaxian governance. | |||

In the aftermath of the monarchy's fall, the triumvirate emerged as the governing mechanism of the First Republic. Comprising three distinct figures, the triumvirate represented a complex amalgamation of political ideologies and aspirations. The triumvirs were: | |||

* Luciano Valera: A charismatic intellectual with staunch republican convictions, Valera championed the ideals of liberty, equality, and popular sovereignty. His political philosophy was deeply rooted in Enlightenment thought, and he sought to institute a system of governance that upheld individual rights early socialist theories. Valera was a driving force behind the crafting of the new constitution, which enshrined fundamental rights, civil liberties, and the establishment of a representative government. Her policy agenda included the expansion of educational opportunities, aiming to create an informed and enlightened citizenry capable of participating actively in the republic's affairs. | |||

* General Santos Navarro: A decorated military commander, Navarro embodied the interests of nationalist and military classes. His vision for Pelaxia revolved around national unity, territorial integrity, and the establishment of a strong defense apparatus after the decline of the Commonwealth. Navarro's militaristic approach was instrumental in consolidating the triumvirate's authority. Navarro's military prowess was instrumental in consolidating the triumvirate's authority and suppressing dissenting voices. He oversaw the restructuring of the armed forces, placing a strong emphasis on discipline and loyalty to the republic. Navarro's vision for Pelaxia was underpinned by the belief that a secure nation could only emerge through military strength and a shared sense of identity. | |||

* Miguel Angel Torrente: A pragmatic statesman with a background in economics, Ortega was a key proponent of economic reforms. His pragmatic ideology emphasized the importance of economic stability, trade expansion, and equitable distribution of resources among Pelaxia's citizens. | |||

Collectively, the triumvirs forged a dynamic coalition that sought to enact sweeping changes across Pelaxia's political, social, and economic spheres. Their collaborative efforts led to the adoption of fundamental republican principles, including the crafting of a new constitution that enshrined civil liberties, established a representative government, and instituted a separation of powers. The triumvirate's commitment to education and enlightenment culminated in the establishment of public schools and cultural institutions, aimed at fostering an informed citizenry. Economically, the First Republic witnessed the implementation of Ortega's policies aimed at revitalizing Pelaxia's economy. Initiatives such as land reforms, trade liberalization, and investment in infrastructure laid the foundation for a more inclusive economic landscape, albeit with challenges in implementation. | |||

However, the triumvirate's governance was not without its challenges. Internal divisions among the triumvirs occasionally strained their unity, and external pressures, including regional conflicts and economic hardships, tested the resilience of the First Republic. These factors culminated in the eventual dissolution of the triumvirate in 1814, marking the end of the First Republic era with the Girojón Restoration. | |||

In conclusion, the First Republic (1804-1814) stands as a transformative chapter in Pelaxian history, characterized by the overthrow of the monarchy, the establishment of a triumvirate governance structure, and the pursuit of republican ideals and the solidification of the Pelaxian Parliament as permanent institution and source of legitimacy. The triumvirs' diverse ideologies and policies left an indelible mark on Pelaxia's political evolution, shaping the nation's trajectory for years to come. | |||

====Shimsha War==== | ====Shimsha War==== | ||

=Girojón Restoration and Constutuional Monarchy (1814 - 1852)= | |||

The fall of the Triumvirate in 1814 and the subsequent restoration of the monarchy under the Girojón dynasty with King Fernando I was primarily driven by a combination of internal political tensions and external pressures. The period of the Triumvirate had witnessed notable achievements in terms of republican ideals, reforms, and social progress. However, a growing faction within the aristocracy and military felt that the republican governance structure was impeding effective decision-making and stability, particularly in times of external threats as many republicanist factions had started to creat independent Revolutionary Juntas that did not recognize the authority of the Triumvir. The military elite believed that the monarchy, which had previously provided a sense of continuity and centralized authority, could better ensure national security and unity. The faction advocating for the monarchy's restoration under an albeit reformed constiutional format with a bicameral system argued that the existence of a single, hereditary head of state would streamline decision-making and enhance Pelaxia's standing in diplomatic circles, allowing for more decisive responses to external challenges. Additionally, some members of the aristocracy saw the monarchy as a means to safeguard their social and economic privileges, which they believed were under threat due to the republican system's emphasis on social equality. | |||

* King Fernando I (1814-1825): The restoration began with the ascension of King Fernando I to the throne in 1814. His reign was marked by efforts to consolidate power and restore the authority of the monarchy. Fernando I sought to balance the demands of the aristocracy and military while also addressing the aspirations of those who had supported the republican ideals. However, internal dissent and external pressures continued to challenge his rule. | |||

* King Felipe II (1825-1837): Following Fernando I's death in 1825, his son, Felipe II, assumed the throne. His reign saw a push for greater centralization of power, economic reforms aimed at boosting trade and agriculture, and diplomatic efforts to reestablish Pelaxia's position on the international stage. However, these efforts often clashed with the republican sentiments that still lingered within some segments of society. | |||

* King Luciano II (1837-1852): Upon the death of Felipe II in 1837, his nephew Luciano II became the monarch. Luciano II faced the challenges of a changing political landscape, as well as the emergence of new social and economic forces. His rule saw efforts to modernize the economy, expand educational opportunities, and maintain Pelaxia's neutrality in the face of increasing regional tensions. However, internal conflicts and the continued push for democratic ideals posed significant challenges to his authority. | |||

=Revolution of 1852: the Republican Wars= | =Revolution of 1852: the Republican Wars= | ||

The fall of the monarchy and the birth of the republic were due to the unpopularity of King Luciano II of the House of Girojon, from his irresponsible behavior and absolutist tendency during the government of the Liberal Party. The monarch's inoperative attitude towards parliamentary government would seem to go against his constitutional role, by not designating the lords recommended by Prime Minister Botello for his House. Luciano ll would come to name a group of ultra-loyal lords that would form the group known as Casta Luciano. | The fall of the monarchy and the birth of the republic were due to the unpopularity of King Luciano II of the House of Girojon, from his irresponsible behavior and absolutist tendency during the government of the Liberal Party. The monarch's inoperative attitude towards parliamentary government would seem to go against his constitutional role, by not designating the lords recommended by Prime Minister Botello for his House. Luciano ll would come to name a group of ultra-loyal lords that would form the group known as Casta Luciano. | ||

The king was in open rebellion against the Law of Lords of | The king was in open rebellion against the Law of Lords of 1826, sanctioned during the reign of his uncle, the late Felipe II. The legislation eliminated the hereditary designation of the lords to his camera, being an emblem of republican dye of the prevailing one Liberal Party. The law marked the "official" re-emerging of the political split between monarchists and republicans and threat of another civil war period, a fracture that would be both social and military. The resistances and inoperacies of Luciano II would provoke such a level of irritation into the military class that a large group of high-ranking, Republican-line officers aligned with the Liberal government would begin to plan his deposition. | ||

Prime Minister Botello would try to reform the Law of Lords, seeking to establish the obligation of the monarch to appoint the lords recommended by head of Government. This proposed amendment was rejected in the House of Lords. Subsequently, Luciano ll would request his resignation to his Chancellor and later the Prime Minister. This action would initiate the military uprising in Agrila in 1852, led by General Solorio Torres. The victory of Solorio Torres, who was beginning to stalk the capital, along with the following uprisings in Monte, Villa Gigonza and Terrero would seal the Republican triumph. Without military or political support, the monarchy had seen its last days. The liberal government eliminated the nobility titles and the House of Lords, and forced Luciano ll into exile. In addition, the administration of Botello would allow the local election of provincial governors through their respective parliaments, from which would benefit the military leaders who participated in the uprising. | Prime Minister Botello would try to reform the Law of Lords, seeking to establish the obligation of the monarch to appoint the lords recommended by head of Government. This proposed amendment was rejected in the House of Lords. Subsequently, Luciano ll would request his resignation to his Chancellor and later the Prime Minister. This action would initiate the military uprising in Agrila in 1852, led by General Solorio Torres. The victory of Solorio Torres, who was beginning to stalk the capital, along with the following uprisings in Monte, Villa Gigonza and Terrero would seal the Republican triumph. Without military or political support, the monarchy had seen its last days. The liberal government eliminated the nobility titles and the House of Lords, and forced Luciano ll into exile. In addition, the administration of Botello would allow the local election of provincial governors through their respective parliaments, from which would benefit the military leaders who participated in the uprising. | ||

| Line 115: | Line 199: | ||

====Raúl Arsenio Solís Vélez: the modern Pelaxian state (1876 - 1896)==== | ====Raúl Arsenio Solís Vélez: the modern Pelaxian state (1876 - 1896)==== | ||

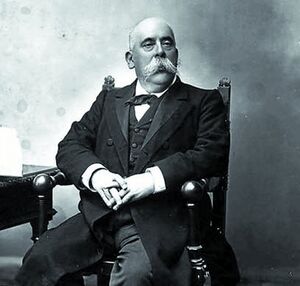

[[File:Raul Eutimio Vélez.jpg|thumb|"Raúl Solís" in 1898|link=Special:FilePath/RAEUT.jpg]] | [[File:Raul Eutimio Vélez.jpg|thumb|"Raúl Solís" in 1898|link=Special:FilePath/RAEUT.jpg]] | ||

Once the Parliament elected him, in the following months federal courts were organized in all the provinces. It also sanctioned a new commercial code. Solís educational policy was oriented to the extension and unification of secondary education, with the idea of extending liberal ideas among young people who could access it; national schools were founded in 30 provinces. The construction of the Federal Pelaxian Railroad network began in | Once the Parliament elected him, in the following months federal courts were organized in all the provinces. It also sanctioned a new commercial code. Solís educational policy was oriented to the extension and unification of secondary education, with the idea of extending liberal ideas among young people who could access it; national schools were founded in 30 provinces. The construction of the Federal Pelaxian Railroad network began in 1872. During his regime it was founded, on November 15, 1880, the Compañía de Construcción y Forjas Ferroviarias as a joint venture bettween 7 different forges and workshops. | ||

The 1880 to 1900 period saw the development of Pelaxia's industrial capacity. Rapid urban growth also enlarged Albalitor, which incorporated its industrial suburb Costilla Blanca into the municipality in 1891. Oil emerged as a significant factor in Pelaxia's economy with the foundation of the CoPeN (Corporación Petrolera Nacional, later PetroPel), the Pelaxian Oil Corporation in 1879. | The 1880 to 1900 period saw the development of Pelaxia's industrial capacity. Rapid urban growth also enlarged Albalitor, which incorporated its industrial suburb Costilla Blanca into the municipality in 1891. Oil emerged as a significant factor in Pelaxia's economy with the foundation of the CoPeN (Corporación Petrolera Nacional, later PetroPel), the Pelaxian Oil Corporation in 1879. | ||

| Line 130: | Line 214: | ||

=====Industry===== | =====Industry===== | ||

Industrialisation progressed dynamically in Pelaxia, and Pelaxian manufacturers began to capture domestic markets from Levantine imports. The Pelaxian textile and metal industries had by 1890 superseded Cartadania and Caphirian manufacturers in the domestic market. Technological progress during Pelaxian industrialisation occurred in four waves: the dye wave (1877–1886), the railroad wave (1887–1896), the chemical wave (1897–1902), and the wave of electrical engineering (1903–1918). Since Pelaxia industrialised later than the rest of Western Ixnay, it was able to model its factories after those of Caphiria, thus making more efficient use of its capital and avoiding legacy methods in its leap to the envelope of technology. Pelaxia invested more heavily in research, especially in chemistry, motors and electricity. The Pelaxian cartel system , being significantly concentrated, was able to make more efficient use of capital. Pelaxia was not weighted down with an expensive worldwide empire that needed defense. | Industrialisation progressed dynamically in Pelaxia, and Pelaxian manufacturers began to capture domestic markets from Levantine imports. The Pelaxian textile and metal industries had by 1890 superseded Cartadania and Caphirian manufacturers in the domestic market. Technological progress during Pelaxian industrialisation occurred in four waves: the dye wave (1877–1886), the railroad wave (1887–1896), the chemical wave (1897–1902), and the wave of electrical engineering (1903–1918). Since Pelaxia industrialised later than the rest of Western Ixnay, it was able to model its factories after those of Caphiria, thus making more efficient use of its capital and avoiding legacy methods in its leap to the envelope of technology. Pelaxia invested more heavily in research, especially in chemistry, motors and electricity. The Pelaxian cartel system , being significantly concentrated, was able to make more efficient use of capital. Pelaxia was not weighted down with an expensive worldwide empire that needed defense. | ||

====1952 Democratic Re-birth==== | ====1952 Democratic Re-birth==== | ||

====1995 Crisis==== | ====1995 Crisis==== | ||

| Line 137: | Line 222: | ||

[[Category:History]] | [[Category:History]] | ||

[[Category:Pelaxia]] | [[Category:Pelaxia]] | ||

{{Template:Award winning article}} | |||

[[Category:2023 Award winning pages]] | |||

[[Category:IXWB]] | |||

Latest revision as of 16:26, 28 July 2024

The history of Pelaxia dates to the Antiquity when the pre-Caphirian peoples of the Kindred coast of the Pelaxian Valley made contact with the Kosalis and the first writing systems known as Paleopelaxian scripts were developed. In 1485, Jerónimo De Pardo, the Grand Duke of Agrila, unified Pelaxia as a dynastic union of disparate predecessor kingdoms vassals to Caphiria; its modern form of a republic was established in 1852.

After the completion of the Union of Alahuela and the creation of the Carto-Pelaxian Commonwealth, the Crown began to explore across the Kindred Sea, expanding into Vallos and marking the beginning of the Golden Age. Until the 1750s, Pardorian Pelaxia was the one of most powerful states in Sarpedon. During this period, Pelaxia was involved in all major Sarpedonian Wars, including the Kindred Wars. Carto-Pelaxian power declined in the latter part of the 18th century.

In the early part of the 19th century, most of the former Pelaxian Empire overseas disintegrated. A tenuous balance between liberal and conservative forces was struck in the establishment of a republic in Pelaxia; this period began in 1852 and ended in 1922. Then came the dictatorship of General Benedicto Álvaro Camargo (1922-1932). His government inaugurated a period ruled by a militarist party, the Restauración Nacional Party, up until 1957. From 1922 the country experienced rapid economic growth in the 1940s and early 1950s. With the death of Federico Pedro Olmos in November 1956 Pelaxia returned to the Federal Republic. With a fresh Constitution voted in 1958.

Antiquity (700 BC - 300 AD)

The Cognati (from Latin: Cognatus) were a set of people that Caphirian sources identified with that name in the wester coast of Sarpedon over the Kindred Sea, at least from the 6th century BC. The Caphirian sources also use the term Pelagi to refer to the Cognati. The term Cognati, as used by the ancient authors, had two distinct meanings. One, more general, referred to all the populations of the cognatish valley without regard to ethnic differences. The other, more restricted ethnic sense, refers to the people living in the western and southern coasts of the Cognatish Valley, which by the 6th century BC had absorbed cultural influences from Vallos. This pre-Caphiravian cultural group spoke the Cognatish language from the 7th to the 1st century BC. Cognati society was divided into different classes, including kings or chieftains (Latin: "regulus"), nobles, priests, artisans and slaves. Cognati aristocracy, often called a "senate" by the ancient sources, met in a council of nobles. Kings or chieftains would maintain their forces through a system of obligation or vassalage that the Caphirians termed "fides".The Cognati adopted wine and olives from the Vallosi. Horse breeding was particularly important to the Cognati and their nobility. Mining was also very important for their economy, especially the silver mines, the iron mines in the Montian valleys, as well as the exploitation of tin and copper deposits. They produced fine metalwork and high quality iron weapons such as the falcata.

Around 4th Century BC, Caphiria sent Caphirian General Ottiano to conquer Cognatia. General Ottiano subsequently defeated the Cognati tribes and conquered Montia. After the Cognati defeat, the valleys were divided into two major provinces, Pelagia Orientis and Pelagia Occidentis. In 197 BC, the Cognati tribes revolted once again in the P. Orientis province. After securing these regions, Caphiria invaded and conquered Albalitoria and Cognatilitoria. The Caphirians fought a long and drawn out campaign for the conquest of Albalitoria. Wars and campaigns in the northwest coast of the Cognati valleys would continue until 16 BC, when the final rebellions of the Litorian Wars were defeated.

-

Cognati jaguar statuette, 2nd to 4th centuries BC.

-

Cognati falcatas in the Museum of Acevilán.

-

Lord of the Hordes, in Jojoba.

-

Cognati relief, Mausoleum of Fontanez, 6th century BC, showing Acirian influence.

-

Reconstruction of Cognati scripture

Due to their military qualities, as of the 4th century AD Cognatish soldiers were frequently deployed in battles in Caphiria.

Caphirian Pelaxia

Throughout the centuries of Caphirian rule over the provinces of Pelaxia, Caphirian customs, religion, laws and the general Caphirian lifestyle, gained much favour in the indigenous population, which was compounded by a substantial minority of Caphirian immigrants, which eventually formed a distinct Pelaxio-Caphirian culture. Several factors aided the process of Caphirianization:

- Creation of civil infrastructure, including bridges, road networks and urban sanitation.

- Commercial interaction within regions and the wider Caphirian world.

- Foundation of colonia; settling Caphirian military veterans in newly created towns and cities.

- The spread of the hierarchical Caphirian administrative system throughout the Pelaxian provinces.

- Growth of Caphirian aristocratic land holdings (latifundia)

Military projects

The military works were the first type of infrastructure built by the Caphirians in Pelaxia, due to the proximity of the valley with the Acirians and Vallosi. The Caphirian fort was the main focus of military strategy passive or active. They could be constructed for short term temporary occupation, tasked with some immediate military purpose, or for garrisoning the troops during the winter, in these cases is built with mortar and wood. They could also be permanent, in order to subdue or control an area in the long term, for which stone was often used to build fortifications. Many camps became stable population centers, eventually becoming real cities. Once a developed into a stable colony or camp, the need to defend these nuclei involved the construction of powerful walls. The Caphirians pioneered the poliorcetic tradition (siege warfare tactics), and over the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, erected substantial walls, usually with the technique of double facing stones with a filling inside of mortar, stone and unique Caphirian concrete. The thickness of this could range from four to even ten meters. There are notable present day remains of Caphirian walls in Babafor, Foronafor, Terrafor, Tarabefa, Montia, Albalitor, Villa Septintria and Colonia.

-

Remains of Caphirian wall in Las Jusonias.

-

Caphirian castle of Agrila.

-

Caphirian wall of Montia at night.

-

Caphirian camp in Villa Septintria.

Civil projects

The ancient Caphirian civilization is known as the great builder of infrastructure. It was the first civilization which dedicated itself to a serious and determined effort for this kind of civil work as a basis for settlement of their populations, and the preservation of its military and economic domination over the vast territory of its empire. The works of most importance are roads, bridges and aqueducts.

-

Remains of Caphirian theatre in Colonia.

-

Aqueduct of Montia: one of the most extensive surviving civil works from Caphirian Pelaxia.

-

Caphirian olive press in Jumilla.

Either within or outside the urban environment, these facilities became vital for the function of the city and its economy, allowing it to supply the most essential necessities; either water via aqueducts or food, supplies and goods through the efficient network of roads and bridges. In addition, any city of at least average importance had a sewer system for the drainage of waste water and to prevent tropical rains flooding the streets. Infrastructure for civilian use was built with intensity, roads that ran through the valley joining Villa Septintria to Termia and Albalitor to Montia: covering the coastal Kindred Sea through the already established routes. Along them a booming trade flowed, encouraging political stability of the territory over several centuries.

Kosal-Caphirian Wars

Caphirian recession and Kosal expansion

In the mid 5th Century AD., the Caphirian Republic would eventually face internal pressure from ambitious leaders such as Luccino Capontinus and Iscallio Maristo, as contention for leadership caused a number of small fights among the ambitious youth and the elder aristocracy. The fighting would culminate with a five year civil war, known now as the War of the Republic, that left 120,000 people dead. The war was in such a frenzy that by the time it had ended, there was no decisive victor and as a consequence, the Republic was on the verge of total collapse.

The undoing of Caphiravian control in the region was the result of four sarpedonian tribes crossing the Cazuano river in 407. After three years of depredation and wandering about southern Pelaxia the Losa, Ladri and Klis moved into Pelaxia in September or October 409. Thus began the history of the end of Caphiravian Pelaxia which came in 472. The Losa established a kingdom in Monti in what is today modern Montia and northern East Pelaxia. The Ladri also established a kingdom in the southern part of the region. The Klis established a kingdom in Albalitore – modern northwest coast. The Caphirian attempt under General Petia to dislodge the Septri from Jojoba failed in 422. Caphiria made attempts to restore control in 446 and 458 with partial success.

In 484 the Kosal established Agrila as the capital of their kingdom. Successive Kosal kings ruled Agrila as patricians who held imperial commissions to govern in the name of the Caphirian Consul. In 585 the Kosal conquered the Losa Kingdom of Montia, and thus controlled a third of Pelaxia.

Kingdom of Agrila

The Agrila Kingdom (Latin: Regnum Agrili) was a kingdom that occupied what is now western Pelaxia from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the successor states to the Caphiravian presence in the Province, it was originally created by the settlement of the Kosali under King Magda in Agrila.The Kingdom maintained independence from the Caphiravian Empire, whose attempts to re-establish authority in Pelaxia were only partially successful. Under King Evaristo - who eliminated the status of imperial commissions - a triumphal advance of the Kosali began. Alarmed at Kosali expansion from Ficetia after victory over the Caphirian armies at Cakia in 479, the Consul sent a fresh army against Evaristo. The Caphirian army was crushed in battle nearby and Evaristo then captured Soratia and secured all of Pelaxian Valley.

Kosali Conquest of Albalitor

Kosal monarch Columbio founded the Kingdom of Albalitor in 618, after he expelled the Klis form its capital and harassed Rastri and Rati settlements in the coastal strip over the Kindred Sea. The Albalitorian kings were happy to make peace with the Sarpic when it suited them, particularly if it left them free to pursue their other enemies, the Merquines. Thus Dadario (757–68) killed 40,000 Sarpics but also defeated the Meriquines and Ciro (774–83) made peace with the Sarpics. Under King Radamancio I (791–842), the kingdom was firmly established. The ethnic distinction between the Cognatish-Caphiravian population and the Kosal had largely disappeared by this time (the Kosal language lost its last and probably already declining function as a church language when the Kosali converted to Catholicism in 589).This newfound unity found expression in increasingly severe persecution of outsiders, especially the Jews. The Kosal Code (completed in 654) abolished the old tradition of having different laws for Caphirians and for Kosali. The 7th century saw many civil wars between factions of the aristocracy. The Kosali also developed the highly influential law code known in Western Sarpedon as the Kosali Code , which would become the basis for Pelaxian law throughout the Middle Ages.

Caphirian Reconquest (500 to 1485)

Middle Ages - Pelaxia under Castrillón rule

Sebastián Pasillas of Castrillón, Despote of Cognata

Under the Catholic Kosali nobles, the feudal system proliferated, and monasteries and bishoprics were important bases for maintaining the rule. The Kosali were caphirianized Southern Sarpedonians and were to keep the “Caphiravian order” against the hordes of Ladri, Rati, Losa and Rastri.

In the year 1175, Sebastián received a summons that would rekindle the flames of his political destiny. The Republic, recognizing his potential and understanding the gravity of the situation in the Pelaxian valley, tasked Sebastián with the "Pacification of Cognata." The Kazofort Rebellion, an epochal struggle for independence from Caphirian dominion, was spearheaded by a fiercely determined leader named Hernán de Kazofort. Hailing from a lineage of Kosali families, Hernán was a man of towering stature and indomitable will.

The seeds of rebellion were sown in the Pelaxian valley as a palpable discontent simmered among the indigenous warlords and noble families. Tensions came to a head when Hernán Kazofort, with his fiery oratory and impassioned rallying cries, galvanized the warlords, known as "Las Familias del Valle" or "The Valley Families," to unite under a common banner. The primary grievance of The Valley Families was the burden of incessant tributes demanded by Venceia, the imperial capital, and the relentless conscription of their sons into the Caphirian legions. Kazofort’s eloquence resonated deeply with the warlords, who had long harbored resentment toward their Caphirian overlords. In a pivotal moment, during a clandestine council at the Kazofort Estate, the lord of the castle brandishing a tattered standard bearing the emblem of a free Pelaxia, declared the cessation of tribute payments to Venceia and the refusal to send their sons to fight in distant wars for the Caphirian Empire. His call to arms ignited a fervor among The Valley Families, and they rallied behind their newfound leader.

Pasillas, arrived in the Pelaxian valley with a modest retinue of loyal soldiers. His initial attempts to establish a foothold were met with fierce resistance from the local lords, notably the formidable Kazofort family.

As the rebellion gained momentum, Caphiria responded with ruthless determination, dispatching legions under the command of Pasillas to quell the insurrection. What ensued was a series of skirmishes and battles across the Pelaxian valley, each marked by Hernán de Kazofort’s astute military leadership and the unwavering resolve of the Valley Families. But in 953, at the climactic Battle of Torrent's End, Hernán de Kazofort met his fate in the heat of combat, valiantly leading his troops against overwhelming Caphirian forces. His sacrifice, however, would not be in vain. His legacy lived on in the hearts of the Valley Families, who continued to wage a relentless struggle for their freedom.

Ultimately, the Kazofort Rebellion exacted a heavy toll onThe Valley Families were specially decimated by Pasillas. Although the end of the rebellion meant the ascendancy of a new Caphiravian despote ruling the valley with autonomy, the rebellion's indomitable spirit would serve as an enduring symbol of Pelaxian resilience in the face of external domination. The legacy of Hernán and the Valley Families would echo through the annals of Pelaxian history, serving as a poignant reminder of the enduring quest for liberty and self-determination.

After years of relentless campaigning and painstaking negotiations, Pasillas succeeded in restoring order to the tumultuous region of Cognata. His crowning achievement was the "Edict of Agrila," issued in 1180, which formally designated him as the Despote of Cognata and moved his royal seat to Albalitor. This historic decree signaled a turning point in the history of both Caphiria and Pelaxia, solidifying Pasillas's legacy as a statesman and military strategist of unparalleled repute. The Edict of Agrila effectively assigned the western part of modern Pelaxia to the House of Castrillón, ruled by Sebastián Pasillas, Despote of Cognata, and the eastern part to the eastern part to its vassal Duke of Agrila. The Castrillón dynasty's 12th-century rise led to the establishment of cities like Alimoche, Fatides, and Barcegas. Concurrently, the Castrillóns expanded their influence, absorbing southern territories and forming alliances. The Montian Confederacy emerged as a political entity during this time, uniting various provinces under its banner. The 14th century witnessed a shift from feudalism to late medieval politics, with the Castrillóns vying against Agrila and Sebardoba for control. Battles and alliances reshaped the geopolitical landscape. In 1469, Despotes Mauhtémoc Castrillón's involvement in the Termia region led to conflicts, including pivotal battles like Alcoy and Jumilla. The fall of Tristán Castrillón in 1477, in which the Montian Confederacy played a role, marked a turning point, signaling the decline of the Castrillón dynasty and the realignment of power dynamics in the region.

Apart from the recognition he must feel towards him, The Republic probably also saw in the appointment of Pasillas, heir to the Castrillóns but also attached to the Pelaxian valley, a factor of stability which could rid the imperial administration of the management of a territory with endemic troubles.

Comunidades Libres

The rise of the Castrillón dynasty gained momentum when their main local competitor, the Kazofort dynasty, died out and they could thus bring much of the territory south of the Rayado River under their control. Subsequently, they managed within only a few generations to extend their influence through Savria in south-eastern regions. Under the Trasfluminan rule, the Picos passes in Montia and the San Alberto Pass gained importance. Especially the latter became an important direct route through the mountains. The construction of the "Devil’s Bridge" (Puente del Diablo) across the Picos Centrales in 1198 led to a marked increase in traffic on the mule track over the pass. While some of the "Free Communities" (Comunidades Libres, i.e. Montia, Cevedo, and Bajofort) were Imperolibertos the Castrillón still claimed authority over some villages and much of the surrounding land. While Cevedo was Imperoliberti in 1240, the castle of Nueva Brine was built in 1244 to help control Lake Lucrecia and restrict the neighboring Forest Communities. In 1273 the rights to the Comunidades were sold by a cadet branch of the Castrillón's to the head of the family, Laín II. Laín II was therefore the ruler of all the Imperoliberti communities as well as the lands that he ruled as a Castrillón.

Laín II instituted a strict rule in his homelands and raised the taxes tremendously to finance wars and further territorial acquisitions. As king, he finally had also become the direct liege lord of the Comunidades Libres, which thus saw their previous independence curtailed. On the April 16, 1291 Laín bought all the rights over the town of Lucrecia and the abbey estates in Bajofort from Abbey. The Comunidades saw their trade route over Lake Lucrecia cut off and feared losing their independence. When Laín died on July 15, 1291 the Comunidades prepared to defend themselves. On August 1, 1291 a League was made between the Comunidades Libres for mutual defense against a common enemy.

The Montian Confederacy

With the opening of the Gastian Pass in the 14th century, the territory of Central Pelaxia, primarily the valleys of Montia, had gained great strategical importance and was granted Imperoliberti by the Trasflumina family of Agrila. This became the nucleus of the Montian Confederacy, which during the 1330s to 1350s grew to incorporate its core of "eleven shires"

The 14th century in the territory of modern Pelaxia was a time of transition from the old feudal order administrated by regional families of lower nobility (such as the houses of Babafort, Estreniche, Fegona, Fatides, Foronafort, Gouganaca, Huega, Tolefe, Terrafort, Rimiranol, Tarabefort, Santialche etc.) and the development of the powers of the late medieval period, primarily the first stage of the meteoric rise of the House of Castrillón, which was confronted with rivals in Agrila and Sebardoba. The free imperial cities, prince-bishoprics and monasteries were forced to look for allies in this unstable climate, and entered a series of pacts. Thus, the multi-polar order of the feudalism of the High Middle Ages, while still visible in documents of the first half of the 14th century such as the Codex Manesse or the Montia armorial gradually gave way to the politics of the Late Middle Ages, with the Montian Confederacy wedged between Castrillón Pelaxia, the Archduchy of Agrila, the Duchy of Sebardoba and the Duchy of Ficetia. Babafort had taken an unfortunate stand against Castrillón in the battle of Scafaleno in 1289, but recovered enough to confront Fatides and then to inflict a decisive defeat on a coalition force of Castrillón, Sebardoba and Abubilla in the battle of Lupita in 1339. At the same time, Castrillón attempted to gain influence over the cities of Lucrecia and Zaralava, with riots or attempted coups reported for the years 1343 and 1350 respectively. This situation led the cities of Lucrecia, Zaralva and Babafort to attach themselves to the Montian Confederacy in 1332, 1351, and 1353 respectively.

The catastrophic 1356 Abubilla earthquake which devastated a wide region, and the city of Abubilla was destroyed almost completely in the ensuing fire. The balance of power remained precarious during the 1350s to 1380s, with Castrillón trying to regain lost influence; Alberto II besieged Zaralva unsuccessfully, but imposed an unfavourable peace on the city in the treaty of Reifort. In 1375, Castrillón tried to regain control over the Savria with the help of Caphiric mercenaries. After a number of minor clashes, it was with the decisive Confederated victory at the battle of Campes in 1386 that this situation was resolved. Castrillón moved its focus westward and lost all possessions in its ancestral territory with the Confederated annexation of Brine in 1416, from which time the Montian Confederacy stood for the first time as a political entity controlling a contiguous territory. Meanwhile, in Abubilla, the citizenry was also divided into a pro-Castro and an anti-Castro faction.

First Termian Wars