Haunted Herald

Not to be confused with the Haunted Herald found in Krasoa

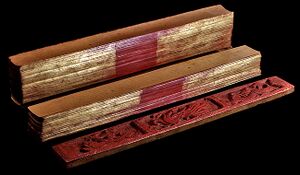

Original 1854 manuscript | |

| Author | Seranda'a |

|---|---|

| Country | Takatta Loa Empire |

| Language | Insuo Loa |

| Genre | Historical satire |

Publication date | 1844 |

| Pages | 135 |

The Haunted Herald, or Ka'áása Teuesetu Nakui'i in the original Insuo Loa, is a famous and the most definitive example of Loa satire. It was written by Seranda'a (1789-1861), a goldsmith and author who was active during the period of the Takatta Loa Empire. Haunted Herald is regarded as his seminal work and reflects his personal views and criticism of the Loafication policies of the time. Seranda'a was an Isi Loa but lived in Disa'adakuo and was in the Rana Flower Group, a literary circle consisting of famous and influential authors of Polynesian descent. As such, he held sympathy for the Non-Loa Polynesians and was revolted by the Loafication policies. Unlike the majority of his circle who were imprisoned or outright executed for going against the government, Seranda'a was spared due to being ethnically Loa by birth, though he was put under house arrest for the rest of his life after the publication of Haunted Herald.

Originally called "Record of Herald Puka" before it became commonly called Haunted Herald in reference to the memorable final scene, the book is set in 1750 in modern day Puertego and centers around Puka ueuePuka, a herald of the Loa Empire sent to the island to announce the glory of the Loa. His interactions with the natives are meant to criticize the perceived idea that the Loa are culturally superior, with many references to the relatively shallow history of the Loa and their propensity towards violence and cultural appropriation, especially in comparison to the more historically established Occidentals. At the time, the mainland Polynesians viewed themselves as being a civilized people akin to the Occidentals on account of their long written history and their previous dominion under Caphiria and the associated diffusion of Occidental culture. Meanwhile, the Loa were viewed as barbaric, illiterate conquerors who "stole" Polynesian culture. Although Loa himself, Seranda'a recognized the mainland influence in his culture and the hypocrisy of Loafication ideals of Loa supremacy. The book was extremely popular and controversial, with the government banning it in 1846 and nearly succeeding in burning every copy. The original manuscript was entrusted to the goddaughter of Seranda'a, who managed to keep it sucessfully hidden until the collapse of the Loa Empire. When she could, she managed to reprint it after which it became one of the modern classics of Loa literature, and one of the few surviving examples of Empire Era Polynesian literature.

Plot

In 1750, the Empire of Takatta Loa is at war with Pelaxia and Caphiria over the island that would become Puertego and decide to send Puka ueuePuka to pacify unruly natives. When he gets to the city of Kueridia, he demands to speak with the chieftain. The people state that they have no chieftain, and so he demands to speak instead with the chieftain's wife. The people take the time explain that if they don't have a chieftain, then they must not have a chieftain's wife. He then demands to speak to their shaman, and so the people bring the Bishop of Kueridia before Puka (the original text refers to the Bishop as a prayer caller of the Kirisitan, likely derived from Seranda'a's understanding of Christianity's relationship to Islam, but lack of knowledge as to what Christianity actually was). He then deliberates with the Bishop over matters of culture and history, which forms the bulk of the book.

He first asks for palm wine, and when the people bring him grape wine, he is repulsed and decapitates the wine bearer. Then he deliberates with the Bishop over the minute details of cuisine, criticizing their food for having "too much flavor" and "not enough plain taro mash". He then insists on eating fish but doesn't recognize it because it's too "spicy", when it was flavored with salt and nothing else. This is likely a reference to the contemporary and current stereotype that Insular Loa food is very bland, but was pushed as the civilized cuisine during Loafication, to largely unsuccessful results. After the unsatisfying dinner, Puka begins to argue with the Bishop about religion. The Bishop lists out all the miracles of Jesus, such as turning a clay dove to flesh (a Muslim miracle), summoning a table laden with food, healing the blind and the lepers and resurrecting the dead. Puka responds with various feats of Isaa'akalaokela (clan spirit of the Imperial Family), none of which are actual feats with the text implying he is making it up on the spot, such as "turning a stone into a comely prostitute" and "summoning a basin of wine and a barrel of opium" and "beating to death the lepers". The Bishop is too stunned to reply and Puka takes this as a sign of victory. He then demands the priest to discuss history. The Bishop goes into extensive detail about the history of the First and Second Imperiums as well as the history of Cartadania Pelaxia and further goes into extensive discussion on the island and its relationship to the surrounding areas. The historiography is inaccurate in places and generally shaky, but is very impressive given the general disinterest of the Loa in the Occident and the Kindreds that they didn't conquer. This discourse is of course largely ignored by Puke, except for when he interjects to boast about a more impressive feat of the Loa, all of which are ludicrously and obviously fake, such as "conquering the moon", "exterminating all Burgundiis" whilst his Burgundii mercenaries stand behind him and "bedding the Caphirian Imperiatrix", the latter of which was done by his own ancestor of course.

After the Bishop finishes, Puka demands his submission. Infuriated, the Bishop refuses stating he would rather die than be subject to such an imbecile. Puka then demands to fight the Bishop, but goes on a long-winded tirade about his formidable might and how he has bested thousands of warriors. He then cuts down the Bishop, and demands to fight his son. The son appears before him and he continues his tirade this time about how the very gods themselves fear his magical abilities. He turns the son to stone and smashes it to pieces. He then demands the Bishop's daughter. The Bishop had no daughter, so a Christian Maiden is sent before him instead. He then tries to impress her by boasting about how brave he was for conquering a "Coscivian Moon Witch" and stealing his magical amulet. The text here is laden with euphemism and implies that he performed sexual favors for the witch in exchange for the amulet. The Maiden catches on and reveals her genitals, temporarily stunning him. She then grabs the amulet about his waist and smashes it to pieces. Enraged, he moves to cut her down, but the Maiden smacks him, sending Puka flying 18 feet backwards. He flees back to the fleet of the Loa Empress and begs at her feet for her to burn the town down and gives an entirely false and nonsensical report of "she-witches" ruling the island, and that ghosts chased him out of the village, which is how the book got its popular title. Although she pretends to care, the Empress is quietly irritated by this imbecile and sends him off on a mission to 'Abssurania' in the hopes that he'll get lost looking for it and die.

Characters

There are a multitude of crowds in the book, such as the townspeople and the Burgundii mercenaries, but there are only four major characters with each representing major aspects of contemporary Loa society. The main central character is Puka ueuePuka, alongside the Bishop of Kueridia. The book centers itelf on their discourse, with the Bishop demonstrating the history and culture of his people and Puka constantly interrupting just to one-up the Bishop and demonstrate the Loa supremacy through increasingly absurd and obviously false stories and boasts. Puka in particular represents the perceived "primitiveness" of the Loa, being a barely literate and hotheaded man who postures over the natives despite his crudeness. The officials who pushed for and controlled the process of Loafication were stereotyped as being particularly brutish and uneducated, and especially prone to outright lying about Polynesian customs in order to make them seem more primitive, much in the same way Puka put down the Bishop at every opportunity with his nonsensical tales. His own name, Puka, is also considered an "uneducated" and "country" name.

The Bishop on the other hand represented the native Polynesians who had a long history and philosophical tradition, as well as being the population most exposed to both Catholicism and Islam which were viewed as more mature compared to the Polynesian and Loa spirituality. Even modern-day Loa consider the Kapuhenasa as being "Islam's little sister". However, the Bishop was still cut down by Puka, a likely reference to the many purges of intellectuals and influential persons during Loafication, including Seranda'a's own friends. The Christian Maiden meanwhile is commonly understood to be a representation of the ingenuity and resourcefulness of the Polynesians, who commonly resisted and tried to maintain their culture in the face of oppression. Seranda'a published the book nearly a decade before Loafication entered its final and most destructive phase and so it has a more hopeful tone. Shortly before his death, Seranda'a was recorded as saying "It seems so foolish in hindsight. I never thought that they would stoop to such lows, that the people would capitulate. But how could they not when their own children were stolen, when their very land was stolen by each other" in regard to this hopeful tone.

The Empress is interpreted as being the actual, cultured Loa like Seranda'a who understood their place in history and understood both the nobility of their culture but also it's 'youth' and he put it. Her banishment of Puka to Abssurania reflects his hope that the educated Loa would recognize the inhumanity of what they were doing and work against Loafication. This was largely an unsucessful plea as evident by the events that unfolded.

Legacy

Haunted Herald has had a significant impact on both contemporary Loa culture and on Loa historiography. It serves as a look into opposing views on Loafication, which is extremely rare due to the systemic destruction of opposing works by the Loa Empire. It, alongside Seranda'a's other works and diaries have enabled historians to chart a timeline of public understanding of Loafication. Prior to the final stages, it was largely understood as an unpopular government policy that would be repealed, which is when the book was written. However, by the final stages when resettlement and mass purges began did it begin to be understood as a genocide, which is further reflected by Seranda'a's later views being extremely hopeless due to living through the most violent years, with the year before his death seeing the mass purge of nearly 2 million people in a country of 30 million prior to Loafication. By the end, Takatta Loa had only 20 million citizens, most culturally Loa. The resulting civil war led to the deaths of an additional 5 million with a million being Polynesians who were subject to ethnic violence by the newly "Loafied" mainland people.

The book remains influential for its quality, being easily readable by modern Loa and being rather humorous even divorced from the context of Loafication. It is often taught in Loa secondary school in conjunction with lessons on Loafication in order to help emphasize the injustice of it. Around 50 schools are named after Seranda'a and the Loafication Memorial has both quotes from Seranda'a written on its southern wall as well as the original manuscripts of all his works, donated by the descendants of his goddaughter.