Northern Confederation: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

|||

| (10 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

| year_end = 2009 | | year_end = 2009 | ||

| event_end = [[Algosh coup]] | | event_end = [[Algosh coup]] | ||

|currency = | |currency = [[Wísdat]] | ||

}} | }} | ||

The '''Northern Confederation''', officially the '''Confederation of the Universal North''', was a country in [[Cusinaut]]. The Confederation, founded in the 17th century, united the [[List of peoples of Cusinaut|dozens of different peoples of eastern Cusinaut]] into a loose confederation able to solve disputes between its members and establish firm rules for trading, and in so doing the new Confederation created nearly three centuries of stability and growth in Cusinaut. Critically, the Confederation also unified the military capabilities of its members, allowing it to consistently defeat efforts by the [[Occident]] to colonize Cusinaut, and even when Occidental colonies were established the strong defense of the Confederation prevented further expansion. By 1800, the Confederation took on greater, codified responsibilities, and in 1847 it adopted a formal written constitution. The Confederation gradually become unable to resolve disputes, especially those involving the emergent Algosh and Honeoye peoples, which led to the decline of its political relevancy. The Confederation continued on through the [[War of the Northern Confederation]], wherein some of its members invited [[Urcea]]n intervention against other members. Despite having been rendered functionally obsolete, the Confederation continued on through the war until the [[Algosh coup]] formally reorganized it. | The '''Northern Confederation''', officially the '''Confederation of the Universal North''', was a country in [[Cusinaut]]. The Confederation, founded in the 17th century, united the [[List of peoples of Cusinaut|dozens of different peoples of eastern Cusinaut]] into a loose confederation able to solve disputes between its members and establish firm rules for trading, and in so doing the new Confederation created nearly three centuries of stability and growth in Cusinaut. Critically, the Confederation also unified the military capabilities of its members, allowing it to consistently defeat efforts by the [[Occident]] to colonize Cusinaut, and even when Occidental colonies were established the strong defense of the Confederation prevented further expansion. By 1800, the Confederation took on greater, codified responsibilities, and in 1847 it adopted a formal written constitution. The Confederation gradually become unable to resolve disputes, especially those involving the emergent Algosh and Honeoye peoples, which led to the decline of its political relevancy. The Confederation continued on through the [[War of the Northern Confederation]], wherein some of its members invited [[Urcea]]n intervention against other members. Despite having been rendered functionally obsolete, the Confederation continued on through the war until the [[Algosh coup]] formally reorganized it. | ||

The Confederation had many different forms over its existence, but the form it took by [[1920]] remained recognizable abroad and reflects its traditional core membership. Its 1920 borders now include the nations of [[New Harren]], the [[Algosh Republic]], the [[Chenango Confederacy]], the [[ | The Confederation had many different forms over its existence, but the form it took by [[1920]] remained recognizable abroad and reflects its traditional core membership. Its 1920 borders now include the nations of [[New Harren]], the [[Algosh Republic]], the [[Chenango Confederacy]], the [[Housatonic|Housatonic Republic]], and [[Caracua]]. | ||

==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

===Pre-confederate Cusinaut=== | ===Pre-confederate Cusinaut=== | ||

===Great Confederation=== | ===Great Confederation=== | ||

Although historians continue to debate the exact originating point of the idea of a Confederation, they are mostly unanimous that the [[Kiravia]]n settlement of the island of [[Porfíria#Beginnings_on_Rovaion|Rovaion]] in [[1654]] provided the immediate impetus for anti-Occidental action. | |||

The areas to the northwest of Cusinaut (modern [[Caracua]]) were slow to embrace the need for the Confederation. However, the rapid growth of [[Thýstara]] to about 12,000 people by [[1700]] increased the frequency of Kiravian excursions into the northern Cusinauti interior. Accordingly, the peoples living there began to join the Confederation beginnining in [[1687]] and completing by around [[1720]], whereby the Confederation extended across Cusinaut from east to west. | |||

====Riot of 1741==== | ====Riot of 1741==== | ||

In [[1741]], the [[Mitei]] of the National Conference met in the city of Kaigwa. | In [[1741]], the [[Mitei]] of the National Conference met in the city of Kaigwa. | ||

===Resisting the Occident=== | ===Resisting the Occident=== | ||

====Constitutionalist shift==== | ====Constitutionalist shift==== | ||

| Line 58: | Line 63: | ||

The Northern Confederation was a {{Wp|confederation}} consisting of dozens of entities including many different cultures and governing systems. Above it all, the unwritten precepts of the Great Confederation, the event which established the polity, served as the central constitution of the Confederation. This unwritten constitution evolved over time, not based on a system of legislative revisions or judicial review but by a decentralized process by which the Great Confederation took on additional mythological meanings and traditions. This took place through the process of cultural interpretation and reinterpretation, a process that some scholars have called "government by {{wp|zeitgeist}}". As the [[Occident]] began to seriously threaten the state in the 19th and 20th centuries, significant reform movements occurred within the Confederation attempting to introduce a constitution. This effort, though not altogether successful, led in [[1847]] to the adoption of the "Received Guidances", written descriptions of the Great Confederation as it meant at that time. From that time on, the Received Guidances took on increasing importance as legal documents as courts within the country were partly reformed to follow a localized version of {{wp|common law}} courts; accordingly from then on they were considered the ''de facto'' constitution of the state. | The Northern Confederation was a {{Wp|confederation}} consisting of dozens of entities including many different cultures and governing systems. Above it all, the unwritten precepts of the Great Confederation, the event which established the polity, served as the central constitution of the Confederation. This unwritten constitution evolved over time, not based on a system of legislative revisions or judicial review but by a decentralized process by which the Great Confederation took on additional mythological meanings and traditions. This took place through the process of cultural interpretation and reinterpretation, a process that some scholars have called "government by {{wp|zeitgeist}}". As the [[Occident]] began to seriously threaten the state in the 19th and 20th centuries, significant reform movements occurred within the Confederation attempting to introduce a constitution. This effort, though not altogether successful, led in [[1847]] to the adoption of the "Received Guidances", written descriptions of the Great Confederation as it meant at that time. From that time on, the Received Guidances took on increasing importance as legal documents as courts within the country were partly reformed to follow a localized version of {{wp|common law}} courts; accordingly from then on they were considered the ''de facto'' constitution of the state. | ||

Although the Great Confederation was ultimately fluid, some of the most important governing institutions of the Northern Confederation were in existence for all or a majority of its existence. For the first century after the Great Confederation, the central body was an institution translated as the National Conference which served as the only unifying element of the Confederation. In the first five decades of the Confederation, the National Conference met once or twice a year in different cities across the Confederation. This first Conference had few direct powers, instead serving as an arbitration board and a committee of correspondence, ensuring that important issues affecting Confederation members were known to the other members. In this form, the Conference usually met with 15 to 40 delegates. The delegates were not elected or chosen by their nation; instead, a number of trusted and well-known individuals were chosen by the nations, often more than one nation at a time. This class of men, known as the ''[[Mitei]]'', would usually come from healers or other respected, learned men throughout the Confederation. In time, however, the motives of the Mitei was called into question, as some who represented multiple nations would receive bribes to favor the interests of one of their clients over another. In [[1741]], such a conflict of interest sparked a riot in Kaigwa, where the Conference met, precipitating a number of changes. The national heads and councils of the Confederation's members imprisoned the Mitei and replaced them with chosen delegates from among their number. The post-1741 Conference then employed a one-nation, one-vote scheme, and accordingly the number of delegates expanded dramatically. It also took on additional legislative powers after 1741. This form of the Conference persisted through the enactment of the Received Guidances in [[1847]]. By that period, the National Conference adopted a three session a year schedule meeting in April, July, and October, rotating host cities but usually held in Kaigwa, [[Housatonic]], and elsewhere; the prominence of these cities, which became a prominent cultural feature of Confederation life, led to the establishment of National Conference halls in these cities. These buildings became politically divisive and represented the growing imbalance of power in Confederation members. The most prominent members of the Confederation began to agitate for proportional representation rather than one-nation, one-vote representation. | Although the Great Confederation was ultimately fluid, some of the most important governing institutions of the Northern Confederation were in existence for all or a majority of its existence. For the first century after the Great Confederation, the central body was an institution translated as the National Conference which served as the only unifying element of the Confederation. In the first five decades of the Confederation, the National Conference met once or twice a year in different cities across the Confederation. This first Conference had few direct powers, instead serving as an arbitration board and a committee of correspondence, ensuring that important issues affecting Confederation members were known to the other members. In this form, the Conference usually met with 15 to 40 delegates. The delegates were not elected or chosen by their nation; instead, a number of trusted and well-known individuals were chosen by the nations, often more than one nation at a time. This class of men, known as the ''[[Mitei]]'', would usually come from healers or other respected, learned men throughout the Confederation. In time, however, the motives of the Mitei was called into question, as some who represented multiple nations would receive bribes to favor the interests of one of their clients over another. In [[1741]], such a conflict of interest sparked a riot in Kaigwa, where the Conference met, precipitating a number of changes. The national heads and councils of the Confederation's members imprisoned the Mitei and replaced them with chosen delegates from among their number. The post-1741 Conference then employed a one-nation, one-vote scheme, and accordingly the number of delegates expanded dramatically. It also took on additional legislative powers after 1741. This form of the Conference persisted through the enactment of the Received Guidances in [[1847]]. By that period, the National Conference adopted a three session a year schedule meeting in April, July, and October, rotating host cities but usually held in Kaigwa, [[Housatonic]], [[Caracua|Kimiornee]], and elsewhere; the prominence of these cities, which became a prominent cultural feature of Confederation life, led to the establishment of National Conference halls in these cities. These buildings became politically divisive and represented the growing imbalance of power in Confederation members. The most prominent members of the Confederation began to agitate for proportional representation rather than one-nation, one-vote representation. | ||

The degree of centralization and unified political authority varied over the course of the Confederation's history. In [[1883]] following the Confederation's victory over [[Urcea]] in its attempted expansion of [[New Harren]], the Confederation convened an emergency standing central government called the Union Directorate. The Union Directorate was invested with the ability to call on any Confederation unit military while also collecting a small voluntary contribution from the members on an annual basis; in [[1912]] it also began to collect a share of all tariff dues collected by the members. With these funds, a small but functional Confederation-wide bureaucratic apparatus was established, allowing the Directorate to sponsor construction of roads, bridges, airports, and other infrastructure. Composed of seven independent Directors, the Union Directorate was nominally under the authority and direction under the National Conference. In practice, the Union Directorate took on the characteristics of an independent central government, renewed annually by the National Conference for the "duration of the crisis" that was continued Occidental pressure in [[Cusinaut]]. The Directorate's independent power was its authority over the military, bureaucracy, and administration, largely ensuring the inability of the Conference to dissolve it. The Union Directorate served as a quasi-executive committee at the pleasure of the National Conference in theory, but in practice many members of the Directorate became independently politically influential, preventing them from being recalled or replaced. National political factions in the 20th century would often form as cliques around individual Directorate members. In the 1960s, these cliques would increasingly take on an ethnic component. | The degree of centralization and unified political authority varied over the course of the Confederation's history. In [[1883]] following the Confederation's victory over [[Urcea]] in its attempted expansion of [[New Harren]], the Confederation convened an emergency standing central government called the Union Directorate. The Union Directorate was invested with the ability to call on any Confederation unit military while also collecting a small voluntary contribution from the members on an annual basis; in [[1912]] it also began to collect a share of all tariff dues collected by the members. With these funds, a small but functional Confederation-wide bureaucratic apparatus was established, allowing the Directorate to sponsor construction of roads, bridges, airports, and other infrastructure. Composed of seven independent Directors, the Union Directorate was nominally under the authority and direction under the National Conference. In practice, the Union Directorate took on the characteristics of an independent central government, renewed annually by the National Conference for the "duration of the crisis" that was continued Occidental pressure in [[Cusinaut]]. The Directorate's independent power was its authority over the military, bureaucracy, and administration, largely ensuring the inability of the Conference to dissolve it. The Union Directorate served as a quasi-executive committee at the pleasure of the National Conference in theory, but in practice many members of the Directorate became independently politically influential, preventing them from being recalled or replaced. National political factions in the 20th century would often form as cliques around individual Directorate members. In the 1960s, these cliques would increasingly take on an ethnic component. | ||

===Constituents=== | |||

Legal conceptions of the sovereignty of the constituent members evolved over time, altering the model of how "local governance" and "constituent nations" worked in the Confederation. The Occidental notions of sovereignty and nationhood were largely foreign to the indigenous Cronan peoples that formed the Confederation in the 17th century. As the peoples of the Confederation were exposed to [[Occidental]] legal treatises and conceptions, the leading legal experts and thinkers of the Confederation began to adapt the Occidental models and systems into their own conception of themselves. | |||

By the end of the 20th century, all of the sedentary members of the Confederation had distinct borders relative to one another. Nearly all of these constituents had strong, deeply-held conceptions of themselves as sovereign entities within a broader Confederation. In many respects, restoration of that sovereignty after the [[Algosh coup]] - and therefore, a return to tradition - was a major motivator to many former constituent peoples in siding with [[Occident]]al powers against [[Algoquona]]. | |||

==Culture== | ==Culture== | ||

| Line 68: | Line 75: | ||

In the 20th century, Kaigwa, [[Housatonic]], and to a lesser extent Tonawandis became major cultural centers within the Confederation, with arts, media, and fashion flowing out of these cities across the rest of the Confederation. In turn, throughout the late 20th century, a culture of mutual enmity and resentment between rural and urban peoples began to grow. | In the 20th century, Kaigwa, [[Housatonic]], and to a lesser extent Tonawandis became major cultural centers within the Confederation, with arts, media, and fashion flowing out of these cities across the rest of the Confederation. In turn, throughout the late 20th century, a culture of mutual enmity and resentment between rural and urban peoples began to grow. | ||

The symbol of the Northern Confederation - its crest and flag - became a long-term legacy of the Confederation. Elements of the flag and its colors have become a staple of state flag design in [[Cusinaut]], with the colors serving as a strong symbol of indigenous polity. Its colors or design elements appear in the flags of [[New Harren]], [[Housatonic]], and the [[Chenango Confederacy]]. | |||

==Economy== | ==Economy== | ||

| Line 79: | Line 89: | ||

[[Category:IXWB]] | [[Category:IXWB]] | ||

[[Category: Cusinaut]] | [[Category: Cusinaut]] | ||

[[Category:Northern Confederation]] | |||

Latest revision as of 17:37, 25 June 2024

This article is a work-in-progress because it is incomplete and pending further input from an author. Note: The contents of this article are not considered canonical and may be inaccurate. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. |

Northern Confederation | |

|---|---|

| 1660–2009 | |

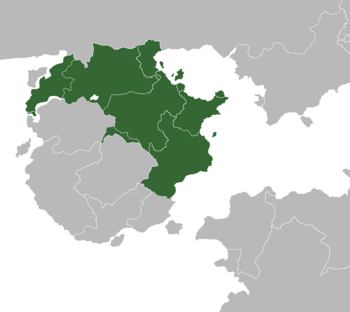

The Northern Confederation in 2000 with modern borders | |

| Status | Dissolved |

| Capital | Rotating; typically Kaigwa or Tepetlcali |

| Recognised national languages | Algosh, Housatonish |

| Religion | M'acunism |

| Government | Initially tribal confederation; later constitutional confederacy |

| History | |

• Great Confederation | 1660 |

| 2009 | |

| Currency | Wísdat |

The Northern Confederation, officially the Confederation of the Universal North, was a country in Cusinaut. The Confederation, founded in the 17th century, united the dozens of different peoples of eastern Cusinaut into a loose confederation able to solve disputes between its members and establish firm rules for trading, and in so doing the new Confederation created nearly three centuries of stability and growth in Cusinaut. Critically, the Confederation also unified the military capabilities of its members, allowing it to consistently defeat efforts by the Occident to colonize Cusinaut, and even when Occidental colonies were established the strong defense of the Confederation prevented further expansion. By 1800, the Confederation took on greater, codified responsibilities, and in 1847 it adopted a formal written constitution. The Confederation gradually become unable to resolve disputes, especially those involving the emergent Algosh and Honeoye peoples, which led to the decline of its political relevancy. The Confederation continued on through the War of the Northern Confederation, wherein some of its members invited Urcean intervention against other members. Despite having been rendered functionally obsolete, the Confederation continued on through the war until the Algosh coup formally reorganized it.

The Confederation had many different forms over its existence, but the form it took by 1920 remained recognizable abroad and reflects its traditional core membership. Its 1920 borders now include the nations of New Harren, the Algosh Republic, the Chenango Confederacy, the Housatonic Republic, and Caracua.

Etymology

In all applicable languages spoken in the Confederation, and usually in Algosh or Housatonish, the name of the state was the "Confederation of the Universal North". The "Universal North" referred not to a specific relative position on Cusinaut but rather both a perceived astronomical position on earth combined with a mystical directional belief related to the practice of M'acunism. Occidental lack of understanding of the tenets of the religion, combined with a desire for simplicity, usually means the state is rendered simply as the "Northern Confederation" in Julian Ænglish and other Occidental languages.

Geography

The Northern Confederation's boundaries varied over the course of its history. In the most consistent 20th century borders of the Confederation, it occupied a position in Cusinaut extending roughly from its northwesternmost point running southeasterly to the Nysdra Sea in modern New Harren. Accordingly, the Confederation in this configuration occupied about half of Cusinaut. Its position in the 20th century, and throughout most of its history, was oriented toward the Nysdra Sea and for much of its history it ran up the entire eastern seaboard of Cusinaut. Due to the breadth of the Confederation, it varied in climate and topography, though much of its territory sat on a plateau-like relatively flat elevation above sea level. The majority of the Confederation's territory featured a subarctic climate with tundra in the northern extremes and an oceanic climate in the southern extreme.

History

Pre-confederate Cusinaut

Great Confederation

Although historians continue to debate the exact originating point of the idea of a Confederation, they are mostly unanimous that the Kiravian settlement of the island of Rovaion in 1654 provided the immediate impetus for anti-Occidental action.

The areas to the northwest of Cusinaut (modern Caracua) were slow to embrace the need for the Confederation. However, the rapid growth of Thýstara to about 12,000 people by 1700 increased the frequency of Kiravian excursions into the northern Cusinauti interior. Accordingly, the peoples living there began to join the Confederation beginnining in 1687 and completing by around 1720, whereby the Confederation extended across Cusinaut from east to west.

Riot of 1741

In 1741, the Mitei of the National Conference met in the city of Kaigwa.

Resisting the Occident

Constitutionalist shift

Domestic power inbalance and decline

Collapse

Government

The Northern Confederation was a confederation consisting of dozens of entities including many different cultures and governing systems. Above it all, the unwritten precepts of the Great Confederation, the event which established the polity, served as the central constitution of the Confederation. This unwritten constitution evolved over time, not based on a system of legislative revisions or judicial review but by a decentralized process by which the Great Confederation took on additional mythological meanings and traditions. This took place through the process of cultural interpretation and reinterpretation, a process that some scholars have called "government by zeitgeist". As the Occident began to seriously threaten the state in the 19th and 20th centuries, significant reform movements occurred within the Confederation attempting to introduce a constitution. This effort, though not altogether successful, led in 1847 to the adoption of the "Received Guidances", written descriptions of the Great Confederation as it meant at that time. From that time on, the Received Guidances took on increasing importance as legal documents as courts within the country were partly reformed to follow a localized version of common law courts; accordingly from then on they were considered the de facto constitution of the state.

Although the Great Confederation was ultimately fluid, some of the most important governing institutions of the Northern Confederation were in existence for all or a majority of its existence. For the first century after the Great Confederation, the central body was an institution translated as the National Conference which served as the only unifying element of the Confederation. In the first five decades of the Confederation, the National Conference met once or twice a year in different cities across the Confederation. This first Conference had few direct powers, instead serving as an arbitration board and a committee of correspondence, ensuring that important issues affecting Confederation members were known to the other members. In this form, the Conference usually met with 15 to 40 delegates. The delegates were not elected or chosen by their nation; instead, a number of trusted and well-known individuals were chosen by the nations, often more than one nation at a time. This class of men, known as the Mitei, would usually come from healers or other respected, learned men throughout the Confederation. In time, however, the motives of the Mitei was called into question, as some who represented multiple nations would receive bribes to favor the interests of one of their clients over another. In 1741, such a conflict of interest sparked a riot in Kaigwa, where the Conference met, precipitating a number of changes. The national heads and councils of the Confederation's members imprisoned the Mitei and replaced them with chosen delegates from among their number. The post-1741 Conference then employed a one-nation, one-vote scheme, and accordingly the number of delegates expanded dramatically. It also took on additional legislative powers after 1741. This form of the Conference persisted through the enactment of the Received Guidances in 1847. By that period, the National Conference adopted a three session a year schedule meeting in April, July, and October, rotating host cities but usually held in Kaigwa, Housatonic, Kimiornee, and elsewhere; the prominence of these cities, which became a prominent cultural feature of Confederation life, led to the establishment of National Conference halls in these cities. These buildings became politically divisive and represented the growing imbalance of power in Confederation members. The most prominent members of the Confederation began to agitate for proportional representation rather than one-nation, one-vote representation.

The degree of centralization and unified political authority varied over the course of the Confederation's history. In 1883 following the Confederation's victory over Urcea in its attempted expansion of New Harren, the Confederation convened an emergency standing central government called the Union Directorate. The Union Directorate was invested with the ability to call on any Confederation unit military while also collecting a small voluntary contribution from the members on an annual basis; in 1912 it also began to collect a share of all tariff dues collected by the members. With these funds, a small but functional Confederation-wide bureaucratic apparatus was established, allowing the Directorate to sponsor construction of roads, bridges, airports, and other infrastructure. Composed of seven independent Directors, the Union Directorate was nominally under the authority and direction under the National Conference. In practice, the Union Directorate took on the characteristics of an independent central government, renewed annually by the National Conference for the "duration of the crisis" that was continued Occidental pressure in Cusinaut. The Directorate's independent power was its authority over the military, bureaucracy, and administration, largely ensuring the inability of the Conference to dissolve it. The Union Directorate served as a quasi-executive committee at the pleasure of the National Conference in theory, but in practice many members of the Directorate became independently politically influential, preventing them from being recalled or replaced. National political factions in the 20th century would often form as cliques around individual Directorate members. In the 1960s, these cliques would increasingly take on an ethnic component.

Constituents

Legal conceptions of the sovereignty of the constituent members evolved over time, altering the model of how "local governance" and "constituent nations" worked in the Confederation. The Occidental notions of sovereignty and nationhood were largely foreign to the indigenous Cronan peoples that formed the Confederation in the 17th century. As the peoples of the Confederation were exposed to Occidental legal treatises and conceptions, the leading legal experts and thinkers of the Confederation began to adapt the Occidental models and systems into their own conception of themselves.

By the end of the 20th century, all of the sedentary members of the Confederation had distinct borders relative to one another. Nearly all of these constituents had strong, deeply-held conceptions of themselves as sovereign entities within a broader Confederation. In many respects, restoration of that sovereignty after the Algosh coup - and therefore, a return to tradition - was a major motivator to many former constituent peoples in siding with Occidental powers against Algoquona.

Culture

The Northern Confederation was an extremely diverse polity, with more than fifty distinctive cultural groups and nations within its confines. Throughout the latter half of the Confederation's history, the Algosh, Housatonish, Honeoye, and Ashkenauk began to influence outsized cultural over the other peoples throughout the Confederation.

In the 20th century, Kaigwa, Housatonic, and to a lesser extent Tonawandis became major cultural centers within the Confederation, with arts, media, and fashion flowing out of these cities across the rest of the Confederation. In turn, throughout the late 20th century, a culture of mutual enmity and resentment between rural and urban peoples began to grow.

The symbol of the Northern Confederation - its crest and flag - became a long-term legacy of the Confederation. Elements of the flag and its colors have become a staple of state flag design in Cusinaut, with the colors serving as a strong symbol of indigenous polity. Its colors or design elements appear in the flags of New Harren, Housatonic, and the Chenango Confederacy.

Economy

Military