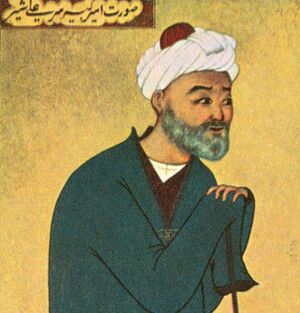

Al-Mahi Sadnajar

This article is a work-in-progress because it is incomplete and pending further input from an author. Note: The contents of this article are not considered canonical and may be inaccurate. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. |

Al-Mahi Sadnajar | |

|---|---|

پاکرابل محسن المحی سیر صدنجار | |

| |

| Born | Pakrabul Muhasin Al-Mahi Sadnajar 1529 |

| Died | 1612 (age 83) |

Pakrabul Muhasin Al-Mahi Sadnajar, better known as Al-Mahi Sadnajar (1529-1612) was a wealthy Audonian merchant living in the Emirate of Zaclaria during the mid-14th and early 15th centuries. Sadnajar is best known for cultivating and selling truffles in Zaclaria and is credited as the "grandfather of truffles" as aristocrats from around the world offered to buy from his collection. By 1570, Sadnajar had built a commercial trade empire and had established trading contacts with the Occidental world. Sadnajar is often cited as the reason why the Truffle Wars occurred, as he was the reason that the West was introduced to truffles. By 1570, Sadnajar's trading contacts reached as far as Burgundie, introducing the West to the exotic flavors of the East. This exchange was not limited to truffles alone; it included a wealth of spices, textiles, and knowledge, fostering a period of cultural and gastronomic fusion that had lasting effects on global cuisine.

Al-Mahi Sadnajar's innovative agricultural techniques, particularly in the cultivation of truffles, transformed the culinary arts and agriculture of Audonia. He pioneered sustainable practices that allowed the desert to yield a bounty of truffles. Moreover, Sadnajar was a patron of the sciences and the mystical arts. He established a brotherhood that combined the spiritual teachings of Sufism with the empirical knowledge of agriculture, creating a unique synthesis that enriched both the soul and the soil. This brotherhood, operating in secrecy, was instrumental in preserving the art of truffle cultivation through generations, long after Sadnajar's time.

History

Early life

Born in 1529, Pakrabul Muhasin Al-Mahi Sadnajar was the son of miners and from a young age was immersed in the culture of extraction and trade that dominated the region. His childhood was marked by the stark contrasts of the Burhaniyah desert's harshness and the underground bounty of the mines of Ishirpur, a region containing the largest mining complex in Zaclaria. The caravan serai, a bustling hub adjacent to the mines, served as his informal school, where traders from across Zaclaria and beyond would rest and share stories. It was here that Sadnajar learned about the broader world, one that extended far beyond the stark beauty of the Burhaniyah desert. The merchants brought with them tales of distant lands, different customs, and exotic goods, sparking a fascination in Sadnajar. The caravan serai provided Sadnajar a unique vantage point to observe the interconnectedness of trade routes that spanned continents. The diversity of languages at the serai granted Sadnajar the ability to quickly learn to communicate with the travelers in their native tongues, a skill that would prove invaluable in his later endeavors. Sadnajar also developed an early appreciation for the fine art of negotiation and trade. Observing the seasoned merchants haggle over prices, he learned to discern the subtle interplay of supply and demand, the psychological nuances of a trade, and the importance of establishing trust and rapport.

Though his family expected him to follow in their footsteps as miners, Sadnajar's interests lay in the world of trade and exploration. He was often found assisting the merchants, absorbing the nuances of their crafts, and sometimes even helping them broker deals. The complexities of trade intrigued him more than the lure of the mines. As Sadnajar grew, so did his reputation within the caravan serai. He was not just a local boy of the Ishirpur Mines anymore; he was becoming a well-known figure among the traders and the regular passersby. His understanding of multiple languages and his ability to negotiate made him a valuable asset to the caravans that stopped at Ishirpur. This exposure to the rhythms of trade and the diversity of cultures also instilled in him a deep sense of cultural appreciation and diplomacy, qualities that would define his later dealings in establishing trade networks. Beyond his interactions at the serai, Sadnajar's wanderlust led him to explore the surrounding desert, where he developed a profound connection with the natural world. The harsh, unforgiving environment of the Burhaniyah desert taught him about survival and adaptation. The desert was a place of contemplation for Sadnajar, a stark contrast to the bustling serai. Here, under the vast expanse of sky, he found the space to think and to dream.

Discovery and cultivation of truffles

During the 1550s, the Ishirpur Mines were beginning to see a decline in yields, casting a shadow of uncertainty over the region's future. Sadnajar's wanderlust often led him into the wilderness surrounding Ishirpur and during one such expedition, he ventured far beyond the usual trade routes, and spent several hours wandering the desert. Eventually, he sought reprieve from the scorching sun under the shade of an Audonian Terebinth tree. As he rested, he noticed a mysterious caravan from the distance. The caravan moved with a silent grace that was almost otherworldly, its travelers garbed in the flowing robes of deep indigo and turmeric, colors that whispered tales of far-off lands. Sadnajar watched as the line of camels and donkeys, heavy with goods unseen, navigated through the mirage-laden heat of the desert. The serenity that hung about them was in sharp contrast to the raucous hustle of the traders he was accustomed to at the serai.

His curiosity piqued, Sadnajar approached them, relying on the amalgam of languages he had mastered to greet the strangers. They were a reclusive sect known as the Shahârpâ Al-Haud, renowned for traversing the most unforgiving terrains to trade in rare goods and knowledge. It was said they carried with them not only physical merchandise but also wisdom gathered from the many cultures they encountered in their travels. In their company, Sadnajar learned of the intricate connections between nature and the subtle art of finding water hidden deep within the desert—knowledge that the Shahârpâ Al-Haud had gathered from ancient texts and their own extensive travels. They spoke of plants like the Audonian Terebinth as being harbingers of life, their presence a map to unseen oases and hidden riches beneath the sand. The Shahârpâ had come in search of a mystery plant that was supposed to exist beneath the earth and possess a unique quality and flavor that was said to be a gift from the harsh landscape itself. This encounter under the Terebinth tree became a turning point for Sadnajar. He was struck by the depth of understanding the Shahârpâ Al-Haud had of the natural world, an understanding that transcended simple trade and delved into the spiritual connection between people and the earth. They treated the desert with a reverent awe, and in their philosophy, Sadnajar found a reflection of his own beliefs—a belief in the sanctity of nature and the wisdom it held. The Shahârpâ Al-Haud traded with Sadnajar, offering him exotic spices and scrolls of knowledge in exchange for them being able to setup their own storefront at Ishirpur. From this mysterious caravan, Sadnajar garnered more than just rare items and esoteric knowledge; he received validation and inspiration to pursue a harmonious relationship with the land. He was emboldened to discover this mystery plant. Guided by the wisdom of the Shahârpâ Al-Haud and the ancient scrolls they traded, Sadnajar set off into the heart of the desert in 1554. The parchments spoke of a hidden treasure beneath the arid wasteland, a plant that was nurtured by the earth’s concealed moisture. The scrolls were cryptic, filled with allegorical references to the stars and the shifting sands, yet Sadnajar, with his intimate knowledge of the desert’s whims, found himself attuned to their secrets.

For weeks he ventured, tracing the celestial maps that the Shahârpâ Al-Haud had given him, allowing the constellations to guide his path. He sought out the places where the Audonian Terebinth trees thrived in sparse solitudes, as they were the living markers that pointed to the life-giving waters hidden beneath the sun-scorched surface. One twilight, as the stars began to pepper the darkening sky, Sadnajar stumbled upon an ancient grove of Terebinth trees, their roots deeply entrenched in the sacred soils of the desert. It was here that the sands whispered to him, urging him to dig. With hands weathered by the desert’s touch, he excavated the earth beneath the trees. Hours passed, and as the moon climbed high, his fingers finally brushed against something unexpected—the rough, earthy skin of a subterranean truffle, the hidden bounty of the Burhaniyah desert. These truffles were unlike any other—their aroma was a tapestry of the harsh landscape, and their was unlike anything he had had before. Sadnajar knew that these were the plants spoken of in the Shahârpâ's scrolls. However, he still needed to identify exactly what sort of plant it was so he could harvest them.

Establishment of trade networks

The establishment of Zaclaria's truffle trade networks under was a feat of both commerce and diplomacy. Recognizing the potential of the truffles as a luxury good, Sadnajar sought to create a network that would leverage the existing caravan trade routes but with a focus on this unique product. He envisioned a web of trade not just within Zaclaria or neighboring regions, but one that stretched across empires. To accomplish this, Sadnajar began by solidifying the infrastructure within Zaclaria itself. He invested in the improvement of roads and the safety of caravans, enabling more traders to travel greater distances with their goods. He ensured that the paths leading to Ishirpur were not only accessible but also secure, establishing a series of waystations that provided rest and resupply points for caravans. Next, Sadnajar extended his influence to neighboring regions, forming alliances with local rulers. He offered them a share in the profits, understanding that mutual benefit was the strongest foundation for any partnership. These leaders, enticed by the wealth the truffle trade promised, agreed to protect the caravans and allow them safe passage through their territories. Sadmajar also utilized his multilingual skills, honed in the caravan serai of his youth, to negotiate contracts and treaties. He employed a cadre of multilingual agents, each well-versed in the art of diplomacy and commerce, who were dispatched to the far corners of the known world. They carried with them samples of truffles, captivating potential buyers with their exotic aroma and flavor.

By aligning with the seasons and the various regional festivals and markets, Sadnajar ensured that the truffles reached the markets when demand was at its peak. The precise timing of these deliveries was critical in establishing the truffles as a rare and sought-after commodity. Eventually, the Guild of Truffle Cultivation and Trade, or Tejarat was established in 1563. The Tejarat ensured the consistency and reliability of these deliveries, building a reputation for Zaclaria as a dependable trading partner. The trade routes themselves became arteries of culture and knowledge, bringing not only truffles but also ideas and innovations from various cultures into Zaclaria. Sadnajar's truffle caravans, therefore, were not merely commercial endeavors but also became conduits for an exchange of knowledge, arts, and philosophy. To further ensure the flow of truffles, Sadnajar introduced innovative preservation techniques. The use of specially designed containers that kept the truffles cool and dry allowed for longer journeys, and thus, the reach of the trade extended even further.