Arcer Bush Wars

| Arcer Bush Wars | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Arcer Colonial Expansion | |||||||||

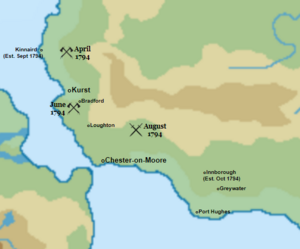

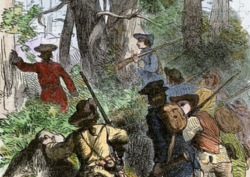

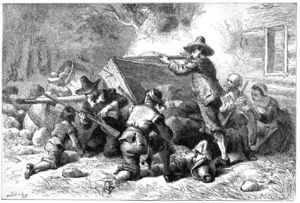

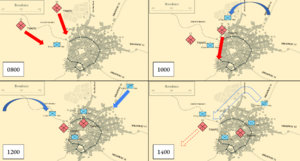

Photos from the Arcer Bush Wars (Clockwise from top left); Carnish settlers defend Loughton in 1798 as part of the First Bush War; Members of 1st Battalion, Royal Arcerion Regiment in 1848 defend their position against an indigenous assault on the Easthampton Settlement during the Second Bush War; Members of the Royal Easthampton Borderers skirmish with native irregulars during the Third Bush War; Infantrymen from the Northlea Rifle Regiment evacuate wounded personnel in a remote part of Northlea in 1968 as part of the Fourth Bush War | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

Indigenous peoples | ||||||||

The Arcer Bush Wars were a series of military conflicts that occurred from raids on the initial Carnish settlements in Arcerion to full-spectrum counter-insurgency operations during the Occidental Cold War. It represents four of the most defining periods in Arcer history, and is a key piece of Arcerion's cultural and historical heritage and is annual celebrated as a key piece of the Arco social fabric. It is catalogued through dozens of museums, exhibits, and battlefield tours, as well as annual national and Governorate days of remembrance and observance. The Bush Wars also coincide with many pivotal moments in Arcer history, from industrialization, to inland expansion, and defense of the newly achieved Arcer sovereignty.

History

Background

The establishment of a Carnish colony and the increased settlement of Occidental peoples threated Indigenous tribes' sovereignty and this created a disputed land claim. Additionally, the killing of an Indigenous man and subsequent fallout of the burial in the Carnish colonial capital of Hughes' Town (later Kurst) caused the A'awaska peoples to begin an increased number of raids and attacks on Arcer settlements, causing then Crown-Governor, John Hughes, to begin military action on behalf of the Carnish Crown to protect the colony. The Arcerion Loyal Militia had also been established the year prior, by Hughes' decree and later ratified by the Carnish Crown.

Carna

Carna had established the Colony of Crona in 1790 as part of Hughes' expedition, and by the time of the war's outbreak, it had expanded this to three towns and multiple smaller settlements in the new colony. The Carnish Crown also saw the settlement as an investment and had been sending additional ships and settlement flotillas to the Malentine and Songun Seas to continue the influx of Gaelic and Anglic peoples into the colony.

Indigenous Peoples

The A'awaska tribe, natives of the Arcer Lowlands, had been scorned due to the murder of an Indigenous man caught stealing in Hughes' Town. Raids on Arcer farmsteads and the killing of Carnish settlers had raised the profile of the tribe, however their raids and forays into Carnish colonial territory were seen more as a form of self-defense of their lands than outright acts of hostility.

First Bush War (1794-1801)

At the beginning of the war, the Carnish Colony of Crona had only a few thousand settlers, and only two main fortifications, that being Fort Ellis in Kurst and the artillery revettment in Chester-on-Moore. Each of the two main settlements could muster approximately a company (~200 men) of militia each, and the sailors and marines of the Carnish naval service provided roughly an additional company of regular forces. Due to the irregular nature of warfare, and the technological overmatch with muskets and cannon, the settlers did not expect an outright pitched battle between themselves and local Indigenous tribes. While some had conducted trading and limited commercial interactions, in general both factions kept to themselves, with limited exposure or attention paid to the other's customs or needs.

1794 - Massacre of the Northern Caravan

In April of 1794, John Hughes authorized an expedition of one hundred and fifty men and women to venture North to establish another town further up the Malentine coast, believing that moving into this territory would allow greater access to Indigenous peoples' trade that flowed through the lowland passes of the Aileach Mountain Range. The one hundred and fifty were selected and given wagons, horses, and a limited number of cattle and other livestock, setting out at the end of the month from Kurst. After two weeks on the road, they were spotted by members of Chief Low'sa's tribe, of A'awaskan allegiance. Chief Low'sa quickly gathered several dozen warriors and set upon the caravan, killing most of the Carnish settlers and running down most of the survivors who escaped the carnage. This was seen as a necessary measure not only to curb the expansion of the colony, but also represented an opportunity to seize guns, livestock, and other goods from the ill-protected caravan.

The few survivors that managed to return to Kurst told the story of the massacre, and John Hughes began provisions to defend the colony. Hughes organized the local militia and established a more rigid training schedule and improved their equipment with the issuing of more modern flintlock muskets to replace many of the aging wheellock weapons, and gave the local citizens access to more cartridges and shot for training. Concurrent to this, in May of 1794 Hughes ordered the company of Carnish marines inland, to foray and try and destroy the members of Chief Low'sa's tribe. The marines augmented their company with some sailors from the Windswept, and set off, encountering a few small bands of Indigenous peoples, and over the next several weeks engaged in a series of small, inconclusive skirmishes.

Chief Low'sa quickly retaliated in June. Gathering three hundred warriors, he set off for a nearby Carnish settlement, which was the newer town of Bradford. Arriving there, many of the local men managed to fire upon the warband as it descended into the town, but a dozen settlers were killed, the remainder retreating to the Anglican Church on a nearby hill, where they used their limited muskets to keep the warband at bay. Unwilling to continue to take casualties to try and break into the church, which was believed to be more heavily defended than it was, Chief Low'sa set fire to the grain mills and the town's grain silo, razing not only Bradford's means of milling and processing their wheat harvest, but destroying their winter stores and jeopardizing the town's ability to sustain itself. With the departure of the warband, only a few men remained to guard the town, with the majority of the inhabitants fleeing in a large caravan to Kurst where they remained for the winter of 1794-1795, sending occasional supplies to Bradford to resupply the dozen-strong garrison in the church.

Hughes now had a massacred caravan and a town that was for all intents and purposes a failed attempt at establishing a new town. The decision was made along with two of the local militia Captains, Simon Thompson and Reginald Cole, to go on the offensive into the Lowlands to the East of Loughton. Hughes issued a Crown-Governor's decree, permitting Thompson's Company to mount an expedition inland for the explicit purpose of finding and destroying Indigenous camps and settlements to protect the Crown's interests. Thompson and his men departed in July, travelling South to first resupply the Bradford garrison, then on to Loughton where they assisted in the construction of additional defenses in the town, and leaving behind a dozen men to assist the local garrison. In Loughton, Thompson called a town meeting, and there the Mayor and local citizens gave them intelligence on where they suspected to be a nearby A'awaska town. Thompson and his militia company set out, finding the encampment nestled between two low rolling hills in the Low Moorland. The men of the town quickly took to arms, but they were few in number and ten of them were cut down quickly by musket fire. Thompson sent a party to flank the town and cut off any more warriors from escaping, killing several more. The remainder of the Indigenous people fled, and they razed the small settlement. Over the next few days, Thompson's men tracked and followed the Indigenous tribes people who had fled, which led them to two more semi-permanent A'awaska towns which they also destroyed. Now late September, Thompson and his men withdrew, spending a week at Loughton to drop off supplies they had looted including wild horses, and then returned to Kurst by October. The resounding victory served as a severe psychological shock to the A'awaska in the Lowlands, as they had not expected the Occidental settlers to venture that far inland with the explicit purpose of fighting, and Chief Low'sa was dishonoured, being killed by his warriors during the winter.

More confident in his position, Crown-Governor Hughes set out another more well-protected caravan to the North, this time encountering no resistance, under the watchful eye of Ensign Francis Kinnaird, for who the town would be named after. Kinnaird was established in the last week of September, marking one of the last major movements of the conflict's first year. Hughes' correspondence with Lieutenant-Governor Richard Hawkesworth of Chest-on-Moore reflected that they also wished to establish new lodgings further into the Lowlands before year's end, and Hughes' authorized fifty men to do so, resulting with Innsborough's founding in October. With both expeditions facing no resistance, and only rumoured reconnaissance by A'awaska scouts, Hughes knew the next year of the war would be a crucial one due to disgracing the local tribes by attacking them in their homes, and due to the long distance ships had to travel to send correspondence back to Carna, it was unlikely they could expect Crown assistance before the end of 1795.

1795 - The Arcer Militia take the Field

Over the winter of 1795 Crown-Governor Hughes organized two additional companies of militia in Kurst, bringing the total number of irregular soldiers in colonial capital to roughly six hundred. With the spring thaw quickly approaching, Hughes convened a War Committee, bringing in militia captains from Chester-on-Moore and Port Hughes. By Crown-Governor decree, he promoted Thompson to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel of Militia in Arcerion, and with the Captaincy of one of Kurst's companies vacated, Thompson recommended an Ensign to fill the empty post. Hughes had been an infantry officer in Carna prior to his commercial ventures in textiles and shipping exports, giving him some understanding of the principles of warfare and the required level of command that he had to exert in such an austere and remote part of the Kingdom's colonial holdings. Hughes outlined the forces at their disposal, three companies in Kurst, one in Chester-on-Moore, smaller garrisons in Port Hughes, Loughton, and Bradford, with small forts and cannon in the two largest Arcer towns. He instructed Thompson to make provisions for inland raids during the Spring, with one company protecting each of the two major towns to prevent them from being destroyed. The War Committee adjourned, setting a date of 15 May for the expedition to begin, under the command of LCol Thompson, with two companies.

Chester-on-Moore Attacked

During the first week of May, with the two companies making preparations for the expedition, the Indigenous tribes under new leadership, Chief Tawaskame, launched a preemptive attack against Chester, as scouts had determined it was the lesser defended of the two towns. Attacking with what was estimated to be six hundred warriors, Tawaskame tried to lure the men of the Chester-on-Moore Militia out into battle by burning farms and outlying buildings of the town, but the militia, under the command of Captain Leighton Grey, were hesitant to venture past the town limits for fear of endangering the townsfolk, who had sought refuge in the pub and church. Tawaskame grew impatient, and sent several dozen of his warriors to attack the pub, which Captain Grey's men defended with continuous volleys of musketry. Between the early morning fog, and the heavy smoke from the muskets, and smoke from burning buildings, Tawaskame became frustrated that he was unable to see progress of the battle, and with a small band entered the town to press the attack and try and destroy more buildings. Upon entering the town, a sharpshooter in the Church steeple identified an indigenous man on horseback with considerable regalia, and shot Chief Tawaskame through the chest, mortally wounding him. The warband collected what dead and wounded they could, but left the field after suffering several dozen killed and wounded. The warband in full retreat, the Chester-on-Moore militia sent riders to Kurst to inform them that they were pursuing them inland. Thompson's column immediately set to march, and they linked up with the band Southeast of Loughton, where the Chester-on-Moore militia, ragged from over a week on forced march to keep pace with the tribesmen, handed off command of the pursuit to the Kurst militia. The combined forces finally caught up with the Indigenous tribesmen in the low foothills East of Loughton, deep in A'awaska territory. There they found the sizeable warband's warriors were drawn from two separate encampments, which had convened while the men were away fighting. A short skirmish ensued, where more A'awaskans were killed and both encampments were burned. The remainder scattering wildly in all directions, Thompson regrouped his forces and withdrew, towards Loughton.

Battle of Loughton

Correspondence from Thompson's personal records in the Arcer National Archives highlights the arrival of a rider to the column informing them of an impending attack on Loughton. "Upon reaching a small copse of trees, I ordered our number of men [400] to make camp and rest as we had been on the march for two nights since firing the native camps. A rider appeared on the horizon, and upon being hailed and recognized as Carnish, informed us of a local warband making for Loughton. I ordered the Serjeants Major to break camp immediately, and we set off again on the march for Loughtown." Heading this warband was Tawaskame's brother, Tewekami, who sought vengeance for his slain brother.

Thompson's column intercepted the tribesmen just a few kilometers from Loughton, catching many by surprise as they overran the sentries and pickets and plunged into a melee with the Indigenous warriors. In the ensuing combat, twenty men of the militia were killed, but three to four times that number A'awaskan warriors were killed and many more wounded. Thompson consolidated his forces and resupplied the garrison at Loughton, who were grateful that the Arcer Loyal Militia had headed off such a large contingent of Indigenous peoples. After burying their dead in Loughton Cemetery, the two militia forces parted ways, Thompson returning with his men to Kurst.

Hughes saw the 1795 campaign as a success, and conveyed to Thompson plans for the following year. A ship bringing additional settlers and supplies, including more muskets and cartridges had arrived, and construction of a larger fort in Kurst began. The Carnish Crown also had seen fit to fund a road connecting Kurst to Chester-on-Moore, improving the existing dirt road used by waggoneers and caravans for the past five years.

1796 - Expansion and Entrenchment

Hughes was expecting a renewed fervor to Indigenous attacks in the summer of 1796, so the War Committee for that year planned an an aggressive series of patrols, forays, and expeditions to ensure the outlying towns of Loughton and Bradford would be protected. On the recommendation of LCol Thompson, the Crown-Governor also dispatched two of the three militia companies in Kurst, one protecting the road construction crews working to the South, and the last to conduct the joint tasks of defending Chester-on-Moore while conducting patrols inland to ensure the security of Innborough and Greywater.

The Carnish Crown also had sent a response, with a flotilla from the Carnish navy, comprised of six frigates and two men-of-war, in addition to provisions to further equip and arm the militia in Arcerion. The flotilla also carried a regiment of Carnish regulars, which immediately set to work improving Fort Ellis, in Kurst, and creating an artillery revettment in Bradford to improve its defensibility. The Crown also gave Crown-Governor John Hughes clear instruction - that he was to take any means necessary to ensure the defense of the colony was successful and the Crown's possessions and lands were not threatened by the A'awska.

Hughes convened his War Committee in the fall of 1796, to begin plans for the 1797 campaign season. Lieutenant-Colonel Thompson now had a regular counterpart, Brigadier Sir Julian Harris, who commanded the Carnish Regular Contingent of Crona (CRCC). During the fall committee meeting, the trio agreed on a course of action for the war's progression. Owing to their innate knowledge of the land, its people, and the enemy, Thompson's irregular militia forces would conduct the offensive action required to keep the A'awskans at bay, while Harris' regular troops and contingent of Royal Carnish Engineers improved fortifications and the road network in Colonial Arcerion. Thompson also requested the additional levy of two more companies of militia, to bring the total number of volunteer soldiers under his command to five companies in Kurst. However Hughes only had the weapons for a fourth company in Kurst, as Chester-on-Moore required supplies in an attempt to raise a second company, which as of yet was still undergoing training and drill. From the Colonial Ledger, or the official accounting of men, equipment, finances, and raw goods in the colony, the garrisons for the winter of 1796-1797 were as follows:

Report on Garrison Forces

- Kurst (Fort Ellis) - Eight Hundred Regulars, Eight Hundred Militia

- Fort Powell - Two Hundred Irregulars

- Chester-on-Moore - Three-Hundred and Fifty Irregulars

Aside from a few minor skirmishes during routine patrols, there were no significant combat actions in 1796, as both sides prepared for the following year.

1797 - Sustained Inland Raiding and Northern Expeditions

With the establishment of a more permanent link between all the coastal towns and fortifications, the infrastructure in the young Carnish colony was beginning to take hold. As per the War Committee's instructions, Thompson used the months of January to March to prepare his men. Four companies of militia trained, drilled, and rehearsed for the first extended campaign in the Lowlands. Thompson emphasized to his officers and men that they would be dislocated from their supply lines for an extended period of time, in an effort to drive the A'awaskan tribes out of the central Lowlands, and ideally set conditions for a Fort or settlement to be established there in 1798. In the first week of April, they departed Kurst, leaving the Regulars to defend the town and work on its defences in their absence.

Central Lowland Campaign

Thompson's plan was to have several partially dislocated companies, that way they could not be attacked en masse and defeated by the A'waskans. He was keenly aware from scouting reports and prisoner testimony that Tewekami had rallied three major tribes to his cause, emphasizing the shared threat they all faced from Arcerion growing as a colony. As such, scouting reports and sightings from Loughton farmers placed the enemy's strength at over a thousand warriors, the largest warband assembled to fight the Occidental settlement thus far.

Thompson's columns raided, razed, and burned through more than a dozen Indigenous encampments and settlements, each time engaging small numbers of warriors, most of whom fought back with bows and arrows, and melee weapons when close enough. Only on rare occasions did they use muskets against the militia, and they were usually rusty, ill-maintained weapons captured from farmers of older manufacture. Thompson began to send dispatches home that after two months of sustained campaigning, none of his four companies had decisively engaged the enemy, despite destroying many of his camps, villages, and supporters. He received no correspondence back, and thus due to his growing concern that the thousand-strong Tewekami Warband had either overrun the postal office in Loughton, or was shadowing him until the right moment to annihilate the entirety of the Arcer militia, he conducted a withdrawal in June to Loughton, where he found the town intact. He left a singular company to defend the town, and withdrew with his remaining three to Kurst, bringing detailed reports of the multi-tribal camps he found, including some tribes that had even migrated towards the Arcer colonies, bringing hardened fighters from the Aileach mountains and foothills into the Lowlands to fight against the Carnish Crown.

The Lowland Campaign was seen as a tactical success, but did not achieve the strategic victory of crippling Indigenous forces' ability to regroup and send out large warbands to disrupt Arcer settlements.

Battle of Inborough

Teewkami during this period was well aware of Thompson's marauding militia forces, however had chosen not to engage them. After the humiliating defeat and casualties at the Battle of Loughton, he was hesitant to engage the Arcer and Carnish forces in open field. Tewekami marched his warband Southeast, away from the A'awaskan homeland and towards Innborough, and avoided burning settlements along the way so as not to arouse suspicion. As well, he had his warriors travel in many smaller groups and mostly at night, to avoid detection by any pickets or roving patrols from Chester-on-Moore. They convened near a small cluster of farms owned by Timothy Laweson, just Northwest of Innborough, which they attacked, killing the settlers and using the buildings as a temporary settlement from which to rest before the oncoming battle. However, one of the children they had neglected to kill managed to make it to Innborough, alerting the local garrison who sent for the company of militia to reinforce them from Chester-on-Moore. Tewekami's scouts however reported that the town had limited defenders and no cannon, and the decision was made on the morning of August 22nd, 1797 to attack.

Attacking at dawn, Tewekami's men experienced no resistance on the outer farms, all of them having been abandoned. Concerned that they had lost the element of surprise, they rushed quickly towards the town hall, which they found surrounded by overturned carts, interlocked with barrels and bags of wheat. The sixty-seven defenders were vastly outnumbered, but were constantly firing at the Indigenous forces, who attempted to breach the small building several times but were repelled. Meanwhile, Captain Edward Murray had force marched the Chester-on-Moore company of militia from the town overnight, and had reached by the evening the town of Greywater. He sent a scout ahead, and on the morning of August 23rd the scout reported that Tewekami's men had taken to rest but still maintained a loose cordon around the town hall, as they waited for their Chief's instruction. Tewekami was faced with a tough decision, as he was aware that reinforcements from Chester-on-Moore would arrive likely by the evening of August 24th. What he had not expected was the extra day's notice from his men's need to rest and their attack on Lawson's farm. He decided he would press his attack and try and capitulate the defenders of Innborough by the evening of the 23rd, and if unsuccessful burn as much of the town as he could. However he was having extreme difficulty controlling his warriors. Unaccustomed to extended visits into Occidental and Arcer towns, they had looted and pillaged much of Innborough, including a large number which had taken to emptying the Pub of its alcohol and beer stores, becoming drunk and disorderly, starting many fights between the multitude of tribes in the warband. Tewekami now had to focus on solving internal discipline issues while also maintaining pressure on the defenders in the town hall.

Late in the afternoon on August 23rd, Captain Murray's men sighted the smoke clouds rising from Innborough's burnt and burning buildings. They pressed on, and shortly before dinner began to sight the Indigenous encampment. Murray devised a plan. He cut fifty of his men away under the command of Lieutenant Johnathan Quicke, to attack the enemy lodgings, while he would take the remainder of the company into the town and relieve the defenders. With the sun setting, the militiamen pressed on, and engaged with musketry the Indigenous forces at 6:34pm, August 23rd, 1797. Tewekami was furious, and attempted to quickly organize a counter-attack, but many of his senior warriors and elders were too busy disciplining soldiers, breaking up fights, drunk, or looting the residences of Innborough. What limited warriors he could muster were cut down in rapidly rising numbers as they tried to attack the Arcer Militia, who were slowly advancing, one line of men firing while two reloaded, then a fresh line advancing several paces down the main street before firing, repeating the process. Tewekami also received a hurried report from a runner that their camp was being burned and many scores of his warriors were being killed by another Arcer militia group. He chose to flee into the night, abandoning his men as he felt the Arcers encircling him. In total, he lost over two hundred warriors killed and the same number wounded, the Arcers suffering a dozen killed and twice that number wounded.

The militiamen consolidated their gains and withdrew to the town hall, expecting a counter-attack the morning of August 24th that never materialized, as the remainder of Tewekami's warband had fled with what loot they still had into the night, effectively ending his tenure as a senior Chieftain of the A'awskan peoples.

1798 - Turning Point and Lowland Settlement

By 1798 the tide had turned decisively in favour of Arcerion, and the A'awaskan tribes had not conducted a raid against a major settlement since the Battle of Innborough, 6 months prior. Hughes had left the colony, on furlough to report to the Carnish Crown on the progress the new colony had made in its first eight years since founding. The colony had a population of approximately 31,000 people as of the census, a mixture of new colonists, births, and naturalized Gaels and Anglic peoples starting new lives.

Crown-Governor Hughes had left on the Windswept in January, with the hopes of returning to the colony before the summer months took hold to help oversee the war effort. By now, Fort Ellis in Kurst, Fort Powell along the coast, and Fort Chester ensured that there was a solid linkage of defensible positions along the King's Highway, which had begun to run the length of the Arcer coast. But Hughes had two main objectives for the year, one military and one economic. He had wished to decisively break the A'awaskans will to fight, and had instructed Lieutenant Colonel Thompson's militia to conduct another long duration raid and expedition into the Lowland to finally destroy what remaining tribes still occupied there after four years of displacement and strife. Following this, the Carnish Regulars, under the command of Sir Julian Harris and accompanied by a civilian caravan, would take one hundred Arcer families inland and establish a new town, serving to solidify the Crown's dominion over the Lowlands, and provide a forward point of resupply and garrison forces to prevent further A'awaskan tribesmen from descending onto the plains from the Aileach mountains. In Port Hughes, the Royal Engineers sought to also establish a new artillery revettment between themselves and Chester-on-Moore, to garrison fifty militia with small field cannon, to defend the King's Highway. Their petition would not be seen by John Hughes until his return in September, but it was granted and by the start of winter weather the positions had been dug and earthen ramparts constructed, with a small barracks for thirty men.

Crown-Governor Recalled to Carna

John Francis Hughes set out for Carna, presenting himself to the Crown in late February of 1798. He brought with him ledgers, detailed accounts of commerce, raw goods, weapons stores, garrison registries, petitions for marriage, population growth census data, and all manner of paperwork to demonstrate to the Crown the immense undertaking that was underway in Crona. The Crown applauded his efforts, awarding him a knighthood, and instructed the newly minted Sir John Francis Hughes to return to Crona with another twenty ships laden with the required resources to establish more permanent facilities and industry, and to expand the colony up the Northern Coast, emphasizing that they wished to see growth into what was at the time bordering Makalan territory.

Battle of Loughton Field

In the colony, provisions under LCol Thompson were being made for the foray inland. He set out in April to begin the raids in the Lowlands, and informed Harris his expected return was to be in mid-August, and they agreed that Sir Harris would meet the militia in Loughton, where they would liaise and trade intelligence and scout reports, with some militia accompanying the Regulars into the lowlands to help identify the ideal location for a new settlement.

The militia by this point had been one of the major driving factors of success in the war. As such, the Carnish Crown had begun to provide regular stipends to compensate the formerly volunteer members for their work. Each man would receive £2/month for service, and a uniform. The brown-faced green jackets became an early form of camouflage, highlighting the irregular and huntsman-heritage that the militia embodied, As well, they were given better cartridge boxes, and one in ten men were being issued with rifled muskets, which despite a parallel industry existing in some Occidental nations, received rapid advancement in Arcerion due to an emphasis on individual marksmanship. The pay, equipment, and support provided to the Arcerion Loyal Militia mean that in just four short years, the original ragtag company of local citizenry with wheellock and matchlock muskets was almost unrecognizable from the semi-professional, hardened force of raiders and back country woodsmen that now marauded the Indigenous peoples of the Lowland Plains.

Arriving in Loughton on the 22nd of April, 1798 with four companies of militia numbering just under one thousand men, and settled in for a period of resupply, and to send scouts out to determine where the Indigenous encampments and settlements were currently located so they could best apply their columns where needed. Several of the scouts returned within two days, reporting of a native column numbering thousands approaching them from the foothills. Thompson took immediate action. He assigned a detachment of skirmishers under Lieutenant John Brown to harass the Indigenous host until preparations could be made. Within an hour, Brown and fifty sharpshooters were afoot and headed along with the scouts who had sighted the warband to delay the enemy's attack. Thompson ordered the remaining militia to begin hastily digging defensive works, including trenches, fascine, and defensible structures given revetting with wheat sacks. Discussions with the mayor also had hastily allowed a sizeable caravan of the townsfolk to depart, removing many civilians and noncombatants from the area, aside from several dozen able bodied men who used their hunting weapons to form a provisional militia company, which Thompson placed in reserve.

Morning Engagement

With the break of dawn on the 26th of April, so did the sound of distant musket fire. By the time 9 o'clock came, the sights of Lieutenant Brown's skirmish company, now reduced to roughly twenty men, could be seen as they sniped and harassed a host of Indigenous warriors larger than ever seen before. Estimated at six thousand warriors, it represented the combined efforts of all nine major A'awaskan tribes to destroy Loughton, Bradford, and then Kurst, as was later discovered during prisoner interrogations. The Indigenous forces attacked through fields of barley, rye, and wheat that were as high as a man's chest. Thompson met the enemy in the field, and engaged them with a violent fusilade of musketry, firing by line in their companies. Indigenous troops fell by the dozen, and as men fired, they moved to the back of the company under Thompson's direction, conducting a slow withdrawal. On the A'awaskan side, there was hesitancy to engage in open battle. The lack of ranged weapons other than bows meant that they were only inflicting a few casualties on the militia, and they were also confused by the presence of music, in the form of the Militia Drum and Pipes band. However three distinct waves attempted to break the militia before lunch, all unsuccessful. The militia at noon withdrew to the town, waiting for the next assault.

Elders within the tribesmen's warband encouraged the younger members to close with the Arcers, to cut them to pieces in the afternoon. However they had left two hundred or more dead or dying on the field in the morning alone, and there was hesitancy to proceed. Regardless, the warband split up into two parties, one which would attack from the front (East) and another from the side (South).

Thompson's lack of ability to scout for fear of sending small parties of men out meant he was forced to react to the next turn of events. He had already sent several riders to Kurst informing Sir Harris that he was embattled by a force at least twice his number, but thus far was holding, but that the Carnish Regulars should prepare to defend Bradford in the instance the militia were routed or killed. By early afternoon, the uneasiness of the militia companies had begun to spread, as they were unused to waiting for indigenous attack, rather they were the raiders and purveyors of violence. To ease the minds of the men, Thompson and the Militia Band rolled a pair of gin casks out into the town square, and section by section men came by to have some gin to lift their spirits and receive a few words of encouragement from Thompson. Spirits raised, they were steeled to begin the afternoon's fight.

Afternoon Engagement

Thompson's mean reported sightings of Indigenous troops massing to the South, and he dispatched a company under Captain Oscar Edward Martin to respond. Martin situated themselves between the town's church and the Inn, placing sharpshooters on the roofs. The assault began shortly thereafter, with both companies embattled and running low on ammunition by dinner. Scores of natives had fell, and a many number of Arcers had been wounded by axe, spear, or arrow as the natives had sometimes closed within bayonet distance. His men low on ammunition, Thompson withdrew deeper into the town to keep his lines intact, as the natives slowly pressured them during their withdrawal, the Militia Band helping stretcher wounded men to the General Goods store, which had become a de facto aid station. Thompson gave the order to fix bayonets as the sun began to set, and the natives set upon them not long after, a fearsome melee breaking out. However the Indigenous warriors were exhausted from a long day of fighting, and the militia held fast, eventually watching the attack evaporate and the warband disappear into the approaching night. Lieutenant-Colonel Thompson was unable to give orders as he had been mortally wounded by an arrow, and would be taken back to Kurst by wagon, where he would die a few weeks later of pneumonia.

The militia held in place for several days, burying their own dead and burning several hundred bodies of native warriors. Relief came in the form of the Carnish Regulars, who took over the defense and garrison of Loughton, bringing with them the townsfolk and families destined to set up the settlement of Lowfield.

Aftermath of the Battle of Loughton Field

The Indigenous morale and spirit was broken, as the largest warband they had assembled in generations had failed to achieve any of its objectives. Leaderless, and without purpose, the hard winter brought about famine and disease from contact with Occidentals, spelling the functional end for the A'awaskan tribes. Those that did not retreat to the Heartland to resettle North of the Aileach Mountains or flee Southeast towards Kiravian-settled Paulastra would continue to be pushed out of the Lowland area, which was now due to its climate and geography declared the 'Governorate of Moorden,' being established by official decree in 1798 with the return of Sir John Hughes.

1799 - Northward Expansion into Makalan Territory

Full on Arcer offensive by this point raids from Greywater inland have driven most indigenous peoples further inland and North, to the foothills and Aileach Mountains

Kurst now has an actual fort with cannons

first cavalry detachment stood up

additionally carnish crown sends three companies of regulars

regulars + militia make an expedition, major battle near bradford between joint militia/regular force

towns east of Kinnaird established x2

1800

fairly calm, limited raids

1801

peace deals and agreements for tribes that are still even remotely close to arcers

arcers quickly adapted to this style of warfare, no line battle shenanigans to be had in Crona

only major engagement of 1801 is a defense of port hughes from a tribe separate from awaska, coming from Paulastra territory so it is brushed off as a one-off

Causes

Forces

War

Aftermath

Second Bush War (1839-1850)

Establishment of Kinnaird, Easthampton, and Craigfearn has occured, Moorden borders mostly done, South end of Northlea is established. War is the main driver into Northlea and has the "River" campaign into the heartland

Causes

Forces

War

Aftermath

Third Bush War (1898-1904)

Norham fully established, same with Moorden. masive campaign to push Northlea to its current boundaires, and the landings and colonizing of Foxhey happened in the 1880s

battle of Erickson's Farm, September 1897 for Kinnaird Grenadiers

Causes

Forces

War

Aftermath

Fourth Bush War (1964-1975)

The Fourth Bush War was a prolonged conflict on the Arcerion border, involving multiple insurgent, guerrilla, or irregular factions, indirectly or directly supported by Telokona, Kelekona, and Titechaxha. It heavily involved all three branches of the Arcerion Armed Forces, and including the rapid rise of modern special forces with the Arcerion Commando Regiment taking a prominent role with its cross-border raids and the Arcerion Rangers conducting long-range patrols behind the operational area.

Causes

The Fourth Bush War began from consistent Arcer farming exports causing a massive economic collapse in Telokona during the spring of 1964, where it was unable to compete with the higher quality and more readily available Arcer grain products. Seeking to destabilize the ability of the Arcer government and its economic power, Telokona began providing arms, supplies, and training to the Free Telokonese People's Movement (FTPM), a socialist group operating in the Innis River Basin (IRB). Continued economic expansion by Arcerion, including the opening of a major shopping port in the city of Oakham, led to an increases in Telokonese support for insurgent forces attacking farmers and rail lines. In solidarity, and seeing the opportunity to cripple or damage a strategic rival, Kelekona and Titechaxha also began mirroring this process, and by 1966 there was a sharp rise in not only attacks on farms, farmers, and rail infrastructure, but government buildings and key civil infrastructure.

Forces

Arcerion

The Arcer Armed Forces at this time were undergoing a period of austerity and force reduction in the wake of the Second Great War. With no major strategic enemies, only regional rivals, the Army had shrunk to its smallest size since 1900, and had only five regular army brigades, with the rest being reserve status or on "short activation" status, wherein for all intents and purposes they were reserve brigades. The Arcer Air Fore also was struggling with budget cuts and austerity measures, as its ability to bring in newer fighter jets, helicopters, and modern radar systems was limited not only due to federal funding, but due to their chronic manning shortages caused by a strong private and public sector employment strategy, making military service the least attractive option at the time. The Royal Arcer Navy played a more limited role in the conflict, but was able to conduct its primary function of ship interdiction and helping to stem the flow of supplies to Kelekona and Telekona through their ports and weapons smuggling ships. Over the course of the war, the Army would introduce new tactics and techniques, as well as modern weaponry for the infantry and supporting arms, and the Air Force would revitalize its rotoary-wing asets and close-air-support platforms. By the war's end, the Army was at a standing eight brigades, with a ninth undergoing readiness and evaluation trials, with companies of reservists regularly deploying into the area of operations for shorter 3-month deployments. New air bases, increased fire control systems, and modern innovations such as precision munitions and early examples of laser-designation and night fighting equipment were all introduced into the Arcer Armed Forces during this period.

Irregular and Guerilla Forces

Originally the Free Telokonese People's Movement (FTPM) was several hundred strong, but by the war's end would number in the thousands. It would soon have a more militant and radical communist offshoot, the Telokonan Worker's Army for a Free Crona (TWAFC). In the smallest operational zone, Operation Kiln, Kelekona supported the Kelekonan Militia for Free Indigenous People (KMFIP). The largest operational area was reflected by the fact that there was three separate terrorist organizations operating there, all supported by Titechaxhan intelligence and security forces. The Free Indigenous Army (FIA), Movement for a Liberated Aboriginal People (MLAP), and the Riverland Tribe Worker's Party (RTWP) numbered by the late-1960s into the thousands. These forces varied widely in terms of equipment, training, experience, and leadership. In general, they were effective as a decentralized quasi-insurgent force. Unable to secure popular support from the Arcer populace en masse, these groups resorted to brutal acts of violence and further isolated themselves from both the native indigenous populations as well as naturalized Arco citizens. As a regular fighting force trying to engage Arcer units in conventional battles, they were quickly destroyed by a combination of artillery fire, air strikes, and aggressive counter attacks by the tactically and operationally superior Arcer units. However, leadership, particularly in the Operation Teflon zones were adept at guerrilla fighting and insurgent-like tactics, making it incredibly difficult to ensure all Arcer farmrs and key points were protected, owing to the long length of the Fourth Bush War.

War

Early Stages

The first recorded attack on an Arcer farm occurred on April 3rd, 1964. The farmstead of the MacIntyre family was attacked by rocket-propelled grenades, small arms fire, with insurgents burning their crops and setting fire to several of their out buildings, such as their barn. The local police, unable to handle the situation, quickly requested help from the Army, who deployed members of 9 Rifle Brigade to respond. Members of the Norham Light Infantry conducted clearance operations along the Lower Innis River, finding evidence of several camps and what they estimated to be several dozen fighters that had since left the area. The Arcer Government convened a special security meeting, and it was decided that they would provide additional security measures by permanently stationing two companies of infantry forward, in what later would become Firebase Emily. The encampment had 105mm howitzers provided by 9 Rifle Brigade's artillery battery, and the two infantry companies spent the rest of April conducting patrols and search-and-seizure operations on indigenous farms in the area trying to find sympathizers.

Subsequent attacks in the nearby area included the deaths of at least five Arcer citizens, one of which was a young child, and this prompted the government to deploy the entirety of 9 Rifle Brigade into the area. By the end of 1964, 9 Rifle Brigade was expecting the arrival of 7 Rifle Brigade from Easthampton. However, as Christmas of 1964 approached, guerilla attacks were now occurring multiple times a week within the Innis River Basin, and every rifle company had experienced a significant amount of skirmishes with guerillas. Concurrent to this, members of the Office of Public Safety and National Security were reporting back on the Telekonan support for the Free Telokonese People's Movement. This prompted the Arcer government to invite the Governor-General for Norham Governorate Adam Wilson, to the Confederate Parliament for an emergency session in December of 1964. Wilson stated emphatically that they required additional support from the Army, and they were struggling to ensure commerce and civil services such as ambulance and fire service, or hydroelectric line maintenance teams could operate freely without becoming harassed by guerillas or bands of marauders. The Arcer government announced the start of Operation Terrace, the permanent deployment of security forces to Norham Governorate, on December 24th, 1964. The following day, the first attacks were recorded in the Titechaxha-Arcerion border, which would soon prompt further deployments.

Operation Terrace

Declared an operation on December 24th, 1964, the mission was simply to end guerilla activity in Norham and Northlea Governorates, assist civil authorities with the protection of key infrastructure such as water treatment facilities, hydroelectric stations, rail lines, and centers of civil authority. Under the command of Colonel Harry "Brock" Tomlinson, the initial phases were the expansion of a series of bases to patrol and operate out of. The largest of the bases in the Terrace zone of operations was Firebase Emily, located at the junction of the Innis and Lower Innis Rivers. It accommodated at its largest point, two six-gun 105mm howitzer batteries, sufficient landing facilities for a dozen helicopters, and enough lodgings for between 800-1,200 men. Tomlinson, the commanding officer of 9 Rifle Brigade, ensured that from these bases the Brigade would patrol, harass and engage Telokonese forces throughout the Innis River Basin. The winter months' wet, rainy, and cool temperatures ensured little fighting and while farmers planted their fields, a second guerilla force began to appear. First indications of the establishment of the Telokonan Worker's Army for a Free Crona was gleaned from an Arcerion Commando Regiment raid in February. After overrunning a guerilla encampment on February 14th, 1965, captured enemy documents and information gleaned from captured prisoners revealed that the encampment did not belong to the FTPM, but rather their new, more aggressive offshoot. Post-mission analysis would reveal that even within the Telekonese-sponsored groups, there was infighting between them, and regular skirmishes.

1965 saw a steady increase of violence throughout the summer fighting season, with 9 Rifle Brigade taking its first casualties in March, with a trio of riflemen from the Norham Light Infantry being killed when responding to a 'call-out' mission, rapidly attempting to reach a sighting or contact area reported to engage enemy forces. They were the first casualties from battle on Arcer soil since the end of the Second Great War. 9 Rifle Brigade also began preparing to receive additional groups of reserve soldiers, with members of 51 and 52 Rifle Brigades taking over base security and aid to civil authority duties by the end of the year. 1966 saw an increase in attacks and also more Arcer casualties. By now, "call-outs" were a daily occurrence, with some instances of soldiers conducting multiple call-outs a day becoming more common. Firebase Emily by this time had turned into a small town, and additional reinforcements from 7 Rifle Brigade were being brought in to help patrol the thick jungle and forests of the Innis River Basin. 1966 however saw a continued rise in Arcer casualties, especially with the continued prevalence of mines and booby-traps. Allegations of detained prisoners abuse began to circulate, however investigations by the Royal Arcer Provost Corps found that there were no instances of prisoner abuse, but two privates in the Norham Light Infantry were disciplined for keeping looted items from enemy encampments.

Widespread combat and pitched battles became more common in 1967, with the Norham Light Infantry accommodating the Norham Foot Grenadiers, who arrived during the summer and with engineers from 9 Combat Engineer Regiment began construction on Firebase Dorothy. The Norham Foot Grenadiers took their first casualties in August, when a supply convoy from 9 Service Battalion was ambushed, leading to many wounded soldiers and eighteen being killed, to that point the single largest loss of life in a single day of the conflict. 1967 also saw the increased use of helicopters, which helped to bring ammunition, water, food, and medical supplies to forward-deployed soldiers and evacuate wounded ones. In the spring of 1968, the Northern portions of Norham Governorate and the Western portions of Northlea were arguably the most dangerous places to live in Crona. Arcer farmers regularly engaged in gun battles to defend their families and properties as hundreds of insurgents continued to roam the countryside, razing farms and killing local citizenry that didn't cow to them. It also represented the first time major engagements between Telekonese backed forces and Arcer regular units occurred in a conventional setting. On September 7th, two battalion-sized elements of TWAFC forces attempted to infiltrate the town of Broadmire, in Northlea, and destroy both the grain silos and the railhead there. Broadmire, which had a historical early 19th-century fort, had been relatively unscathed to this point. Over a period of six hours, multiple companies of 1st Battalion, Norham Light Infantry (1NLI) were airlifted in by helicopters, and proceeded to fix and destroy one of the two enemy units, with a squadron of armoured reconnaissance vehicles from the King's Arcerion Lancers engaged the routing second element and forced them to withdraw, with the TWAFC forces suffering heavy losses, with the body count from the Arcer soldiers on the ground totaled at 278 enemy, with likely that same amount wounded. During the Battle of Broadmire, 33 Arcer soldiers were killed, the majority from B Company, 1st Battalion, Norham Light Infantry Regiment, as they had been the initial soldiers responding to the call-out. Broadmire showed for the first time that Telokonese forces were willing to stray out of the rural areas and engage Arcer forces as peers, even if the result was disastrous. This shift in strategy prompted Colonel Tomlinson to staff a memo requesting the government deploy Arcer commandos across the border to disrupt the enemy and prevent such large-scale movements of enemy fighters from occurring again. The request granted, the first Arco Commando Regiment patrols and raids began to be conducted on Christmas Day, 1968.

| Year | Reported Attacks | Estimated EKIA | Arcerion Casualties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1964 | 22 | 27 | 0 |

| 1965 | 113 | 198 | 3 |

| 1966 | 179 | 288 | 38 |

| 1967 | 248 | 466 | 177 |

| 1968 | 345 | 754 | 190 |

| 1969 | 399 | 1,199 | 265 |

| 1970 | 524 | 2,158 | 321 |

| 1971 | 467 | 1,835 | 176 |

| 1972 | 451 | 1,797 | 152 |

| 1973 | 320 | 976 | 104 |

| 1974 | 290 | 868 | 53 |

| 1975 | 80 | 556 | 29 |

| Total | 3,438 | 11,122 | 1,508 |

Operation Kiln

Operation Teflon

Aftermath

Legacy

legacy stuff

Effect on Arcer Culture and Politics

Arco-Indigenous Relations

In Popular Culture

At least 1 movie a la Zulu

At least 1 movie Vietnam-ish

documentary about first bush war

reenactments of first bush war