Carto-Pelaxian Commonwealth: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary Tag: 2017 source edit |

mNo edit summary Tag: 2017 source edit |

||

| (20 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox country | {{Infobox former country | ||

|conventional_long_name = | |conventional_long_name = Westlands Republic of the Two Nations | ||

|native_name = | |native_name = ''República de las Dos Naciones de las Tierras Occidentales'' ([[Pelaxian language|Pelaxian]])<br>''República das Duas Nações das Terras Ocidentais'' ([[Cartadanian language|Cartadanian]])<br>''Res Publica Utriusque Nationis Terras Occidentales'' ({{wp|Classical Latin|Latin}}) | ||

|life_span = 1632-1795 | |||

|image_flag = Banner of Carto-Pelaxia.svg | |||

|alt_flag = Banner | |||

|image_flag = | |flag_border = no | ||

|alt_flag = | |image_flag2 = <!--e.g. Second-flag of country.svg--> | ||

|flag_border = | |alt_flag2 = <!--alt text for second flag--> | ||

|image_flag2 = | |flag2_border = <!--set to no to disable border around the flag--> | ||

|alt_flag2 = | |image_coat = Definitve CoA.png | ||

|flag2_border = | |alt_coat = Coat of Arms | ||

|image_coat = | |||

|alt_coat = | |||

|symbol_type = | |symbol_type = | ||

|national_motto = | |national_motto = "Vinculum Liberorum et Fidelium" | ||

|englishmotto = | |englishmotto = (''Bond of the Free and Loyal'') | ||

|national_anthem = | |national_anthem = ''None'' | ||

|royal_anthem = | |royal_anthem = {{wp|Marche Henri IV|Marcha Jerónimo III}} | ||

|other_symbol_type = | |other_symbol_type = <!--Use if a further symbol exists, e.g. hymn--> | ||

|other_symbol = | |other_symbol = | ||

|image_map = | |image_map = | ||

|loctext = | |loctext = <!--text description of location of country--> | ||

|alt_map = | |alt_map = <!--alt text for map--> | ||

|map_caption = | |map_caption = Location of XXX (dark green)<br>In [[XXX]] (gray) | ||

|image_map2 = | |image_map2 = <!--Another map, if required--> | ||

|alt_map2 = | |alt_map2 = <!--alt text for second map--> | ||

|map_caption2 = | |map_caption2 = <!--Caption to place below second map--> | ||

|capital = | |capital = [[Albalitor]] | ||

|largest_city = | |largest_city = capital | ||

|official_languages = | |official_languages = {{hlist|[[Pelaxian language{{!}}Pelaxian]]|[[Cartadanian language{{!}}Cartadanian]]|{{wp|Classical Latin|Latin}}}} | ||

|ethnic_groups = | |common_languages = {{hlist|[[Caphiric Latin]]|{{wp|Aromanian language|Montanaran}}|{{wp|Venetian language|Savrian}}}} | ||

|religion = | |ethnic_groups = | ||

|demonym = | |religion = [[Catholic Church|Catholicism]] (official)<br>[[Caphiric Church|Imperial Catholicism]]<br>{{wp|Protestantism}}<br>{{wp|Judaism}}<br>{{wp|Islam}} | ||

|demonym = [[Pelaxians|Pelaxian]]<br>[[Cartadanians|Cartadanian]] | |||

|government_type = {{nowrap|{{wp|federal monarchy|Federal}} {{wp|parliamentary system|parliamentary}}}} {{wp|elective monarchy}} | |||

| | :{{nowrap|''{{wp|De facto}}'' {{wp|parliamentary republic|parliamentary}}}} {{wp|republic}} (1723-1773) | ||

| | |title_leader = [[Carto-Pelaxian Emperor|Emperor]] | ||

| | |leader1 = [[Jeronimo I & III of Carto-Pelaxia|Jeronimo I & III]] | ||

| | |year_leader1 = 1632-1661 | ||

| | |leader2 = [[Sebastian I of Carto-Pelaxia|Sebastian I]] | ||

| | |year_leader2 = 1661-1699 | ||

| | |leader3 = [[Sebastian II of Carto-Pelaxia|Sebastian II]] | ||

| | |year_leader3 = 1699-1723 | ||

|established_event1 = Union of Alahuela | |leader4 = ''None'' (Interregnum) | ||

|established_date1 = | |year_leader4 = 1723-1773 | ||

| | |leader5 = [[Felipe I of Carto-Pelaxia|Felipe I]] | ||

| | |year_leader5 = 1773-1795 | ||

| | |title_representative = [[High Commissioner of Pelaxia|High Commissioner]] (Pelaxia) | ||

|currency = | |representative1 = | ||

|title_deputy = [[High Commissioner of Caridonia|High Commissioner]] (Cartadania; pre-1710)<br>[[President of Cartadania|President]] {{nowrap|(Cartadania; post-1710)}} | |||

|deputy1 = | |||

|year_deputy1 = 1632-1648 (first) | |||

|deputy2 = | |||

|year_deputy2 = 1793-1795 (last) | |||

|legislature = [[Royal Courts of Carto-Pelaxia|Royal Courts]] | |||

|upper_house = [[Supreme Court of Carto-Pelaxia|Supreme Court]] | |||

|lower_house = [[Grand Court of Carto-Pelaxia|Grand Court]]<br>[[General Court of Carto-Pelaxia|General Court]] | |||

|sovereignty_type = Formation | |||

|established_event1 = [[Union of Alahuela]] | |||

|established_date1 = 1632 | |||

|established_event2 = De Pardo line extinguished | |||

|established_date2 = 1723 | |||

|established_event3 = First Calamity | |||

|established_date3 = 1772 | |||

|established_event4 = Girojons enthroned | |||

|established_date4 = 1773 | |||

|established_event5 = Second Calamity | |||

|established_date5 = 1793 | |||

|established_event6 = Third Calamity | |||

|established_date6 = 1795 | |||

|currency = [[Old Real]] | |||

}} | }} | ||

The '''Carto-Pelaxian Commonwealth''', formally known as the ''' | The '''Carto-Pelaxian Commonwealth''', formally known as the '''Westlands Republic of the Two Nations''' and often referred to as '''Carto-Pelaxia''', the '''Pelaxian Empire''', or simply as the '''Kindreds Republic''', was a {{wp|federation|federative}} {{wp|real union}} between the [[Kingdom of Pelaxia]] and the [[Caridon Federal Republic]], which became the [[Cartadania|Federative Republic of Cartadania]] after the [[Luso Rebellion]] of 1710, that existed from the enactment of the [[Union of Alahuela]] in 1632 until its dissolution after the Third Calamity in 1795. This state represents the [[House of De Pardo|House de Pardo]] at its zenith and was among the largest and most populous countries in 17th-to-18th-Century [[Sarpedon]]. At its largest territorial extent, during the reign of [[Sebastian II of Carto-Pelaxia|Emperor Sebastian II]], the Commonwealth covered nearly one million square kilometres, or about four-hundred thousand square miles, in territory and sustained a vast, multi-ethnic population of about twenty-two million subjects. It was an officially {{wp|trilingual}} state with its official languages being [[Pelaxian language|Pelaxian]], [[Cartadanian language|Cartadanian]], and {{wp|Classical Latin|Latin}}. | ||

Carto-Pelaxia was formed in July of 1632 with the signing and enactment of the Union of Alahuela by the aristocracies of Pelaxia and Caridonia which had liberated their respective lands from [[Caphiria]] as a result of religious disagreements which had emerged due to the [[Great Schism of 1615]] and the subsequent establishment of the [[Caphiric Church|Imperial Church of Caphiria]]. Pelaxia was the first country to revolt against Caphirian rule in the early 1620s, followed by Caridonia at around the same time, with the former greatly aiding in the latter's fight for independence. Due to the starkly different political cultures of the two newly-independent nations, the resulting state that had emerged carried elements of both monarchism and republicanism in an effort to please both nations. | |||

The | The Commonwealth had possessed numerous features that were, and often still are, considered unique amongst contemporary and modern states. There was a strict system of checks and balances upon the [[Carto-Pelaxian Emperor|Emperor]] which were enforced by the {{wp|tricameralism|tricameral}} [[Royal Courts of Carto-Pelaxia|Royal Courts]] which consisted of the [[Supreme Court of Carto-Pelaxia|Supreme Court]], which was a {{wp|privy council}} that consisted of senior government officials and members of the clergy, the [[Grand Court of Carto-Pelaxia|Grand Court]], which consisted of junior government officials and members of the clergy, and the [[General Court of Carto-Pelaxia|General Court]], which consisted of the nascent merchant class and generals of the armed forces. The Royal Courts also had the responsibility to elect a new Emperor from the House de Pardo should the previous one pass away, though ultimately only the Supreme and Grand Courts held sway over the election, with the General Court holding only purely advisory powers. This system of government has served as a precursor to modern {{wp|constitutional monarchy}} and {{wp|liberal democracy}} due to its high enfranchisement. Constitutionally, the nations of the Commonwealth were supposed to be equal, but in actuality successive Emperors have more often than not favoured Cartadania (Caridonia pre-1710) despite it being officially a republic. | ||

The | The overall multi-ethnic makeup of the Commonwealth gave it a high level of ethnic and religious tolerance as was guaranteed by the [[Constitution of the Two Crowns]]. Pelaxianisation and caridonisation (cartadanisation) and conversions to [[Catholic Church|Catholicism]] were voluntary throughout the Commonwealth's history despite the Catholic Church holding official status. | ||

After | After nearly a century of prosperity and stability, the Commonwealth would enter a period of rapid decline with the sudden death of Emperor Sebastian II in 1723 without any living relatives, thus extinguishing the de Pardo lineage. Because there was no provisions to elect a new royal house in the event that the de Pardo line died off, the Royal Courts decided to govern the country without an Emperor and thus entered into a fifty-year-long {{wp|interregnum}} period, effectively becoming an aristocratic republic. Without a royal figurehead to keep the nobility more or less in line, the inherent flaws of the Carto-Pelaxian system began to emerge. Although semi-democratic, there were no formal political factions or parties which meant that the enfranchised nobility, which went up well into the hundreds, were largely independent from one another. This became especially egregious whenever legislative or executive actions were put up to a vote as legislation that had a clear majority of support were often killed by a single noble who would constantly add on frivolous and often unpopular amendments, things that would have been vetoed by the Emperor, which would either stall the passage of the proposed legislature or even defeat it outright. As a result, the Commonwealth quickly became unstable with its enemies more than eager to take advantage. | ||

=Name= | |||

The chaos and lack of significant progress during the interregnum would culminate in the First Calamity in 1772 when the Commonwealth lost territories to a resurgent Caphiria and neighbouring Slavic realms. The traumatic loss would finally force the Royal and Grand Courts to finally elect a new Emperor, hastily electing [[Felipe I of Carto-Pelaxia|Emperor Felipe I]] of the [[House of Girojon]]. However, the election of Felipe I failed to keep the Commonwealth from collapsing. The Second Calamity in 1793 saw even further southern lands being lost as well as a viral outbreak which eliminated three-quarters of the nobility that further plunged the realm into instability. Despite various reforms being passed in an effort to rationalise the overly complicated political system, the Third Calamity in 1795 would see Carto-Pelaxia dissolve with the Girojon monarchy, now demoted to a royal family instead of an imperial family, retaining control over [[Kingdom of Pelaxia (1795)|Pelaxia]] and the republican government retaining control over Cartadania. The lingering trauma from the collapse of the Commonwealth would serve as one of the causes behind the [[Pelaxian Revolution]] in 1803 and the establishment of the [[First Pelaxian Republic]]. | |||

==Name== | |||

The official name of the state was the United Kingdom of Cartadania and Pelaxia (Cartadanian: Reino Unido de Cartadania e Pelaxia, Pelaxian: Reino Unido de Cartadania y Pelaxia, Latin: Regnum Unitum Cartadanium Pelagium) and the Latin term was usually used in international treaties and diplomacy. | The official name of the state was the United Kingdom of Cartadania and Pelaxia (Cartadanian: Reino Unido de Cartadania e Pelaxia, Pelaxian: Reino Unido de Cartadania y Pelaxia, Latin: Regnum Unitum Cartadanium Pelagium) and the Latin term was usually used in international treaties and diplomacy. | ||

| Line 68: | Line 91: | ||

Other informal names include the 'Republic of Nobles' and the 'First Commonwealth of Sarpedon.' | Other informal names include the 'Republic of Nobles' and the 'First Commonwealth of Sarpedon.' | ||

=History= | ==History== | ||

==Prelude (1283–1618)== | ===Prelude (1283–1618)=== | ||

The Province of Pelaxia and the Province of Cartadania underwent an alternating series of wars and alliances across the 13th and 14th centuries. The relations between the two states differed at times as each strived and competed for political, economic or military dominance of the region. In turn, Pelaxia had remained a staunch ally of its northern ruler, Caphiria. | The Province of Pelaxia and the Province of Cartadania underwent an alternating series of wars and alliances across the 13th and 14th centuries. The relations between the two states differed at times as each strived and competed for political, economic or military dominance of the region. In turn, Pelaxia had remained a staunch ally of its northern ruler, Caphiria. | ||

| Line 88: | Line 111: | ||

The intention of the union was to create a common state under Albalitorian law, with the support of the ruling oligarchy in the Montian Confederacy. Castrillón would gain access to the trade passes through the Picos into the Dominate of Caphiria, while the Confederates would gain access to Albalitorian ports and sea routes. Thus, in the Jeronimian period, Pelaxia developed as a feudal state with a predominantly agricultural economy and an increasingly dominant mercantile nobility. | The intention of the union was to create a common state under Albalitorian law, with the support of the ruling oligarchy in the Montian Confederacy. Castrillón would gain access to the trade passes through the Picos into the Dominate of Caphiria, while the Confederates would gain access to Albalitorian ports and sea routes. Thus, in the Jeronimian period, Pelaxia developed as a feudal state with a predominantly agricultural economy and an increasingly dominant mercantile nobility. | ||

==Union of Alahuela (1632)== | ===Union of Alahuela (1632)=== | ||

==Apex and the Golden Age ( | |||

== | <gallery mode="packed" widths="250" heights="250"> | ||

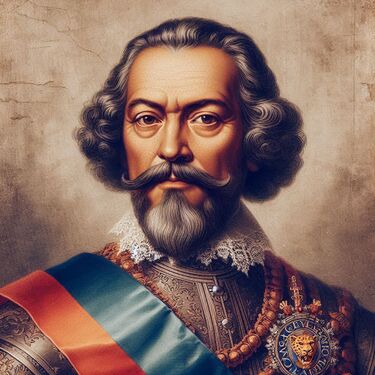

== | File:31de2a7d-5319-45fc-a253-ed2edda2e9b7.jpeg|Emperor Jerónimo III, Despote of Pelaxia and Cartadania, King of Savria and Lord Protector of the Jusonias. | ||

== | File:63322b6c-0781-4f84-8309-71fcbd61356c.jpeg|Braçayda de Fonseca, Plenipentontial Minister of the States of Cartadania | ||

=State organization and politics= | File:1a05a447-2d73-4782-8487-a0815c465bac.jpeg|Hipólito Francisco de Huerva, Royal Chancellor of Pelaxia. | ||

==Magnate oligarchy== | </gallery> | ||

==Late reforms== | |||

=Economy= | ===Apex and the Golden Age (1673–1723)=== | ||

=Military= | |||

=Culture= | ====Kindred Wars==== | ||

=Science and literature= | |||

=Art and music= | ===Interregnum (1723–1772)=== | ||

=Architecture= | |||

=Demographics= | ===First Calamity and Girojons enthroned (1772-1773)=== | ||

=Religion= | |||

=Languages= | ===Further calamities (1773–1795)=== | ||

=Legacy= | |||

=Notable people= | ==State organization and politics== | ||

===Magnate oligarchy=== | |||

===Late reforms=== | |||

==Economy== | |||

The economy of the Commonwealth was predominantly based on agricultural output and overseas trade through the southern route into Audonia, though there was an abundance of artisan workshops and manufactories — notably paper mills, leather tanneries, ironworks, glassworks and brickyards. Some major cities were home to craftsmen, jewellers and clockmakers. | | |||

The majority of industries and trades were concentrated in the Kingdom of Pelaxia; the Republic of Cartadania was more rural and its economy was driven by farming and clothmaking. Mining developed in the north-east region of Pelaxia which was rich in natural resources such as lead, coal, copper, iron ore, gold. The currency used in Carto-Pelaxia was the (xxxx) and its subunit, the (xxxx) Foreign coins in the form of (xxxxx) were widely accepted and exchanged. | |||

The country played a significant role in the supply of Levantia and Caphiria by the export of grain (rye), cattle (oxen), exotic fruits, furs, timber, linen, coffee, peanuts, coconut oil, palm oil, poultry meat, corn and cotton. Cereals, coffee, cattle and fur amounted to nearly 90% of the country's exports to Levantine markets by maritime trade in the 16th century. From Albalitor, ships carried cargo to the major ports of the (XXXX), such as (XXXX) and (XXXXX).The land routes, mostly to the Caphirian provinces of the such as the cities of (XXXXX) and (XXXXX), were used for the export of live cattle (herds of around 50,000 head) hides, salt, tobacco, hemp and cotton from the Cartadania. In turn, the Commonwealth imported wine, beer, fruit, luxury goods (e.g. tapestries), furniture, fabrics as well as industrial products like steel and tools. Much of the product variety and commercial capacity of the Commonwealth was deeply dependent on the trade with Audonia through the southern route. Most of the Commonwealth production is exclusively based on slave labor supplied by Daxian traders in special enclaves in the far east continent. | |||

The slave system was inherited from the Caphiric socio-economic structure of the Carto-Pelaxian provinces. Though much of it has had extensive reforms from the local nobility through the drafting of feudal law codes that evolved slavery into serf status regimes especially associated with a noble. The increasing demands for tropical products from the Levantine economies increased the need for efficient and cheap labor, which was quickly supplemented through the dominance of overseas territories such as Vallos or trade with Daxia. | |||

Slave labor was the driving force behind the growth of the sugar and coffee economy in Carto-Pelaxia, and coffee was the primary export of the Cartadania from 1600 to 1650. Gold and diamond deposits were discovered in Pelaxia in 1690, which sparked an increase in the importation of enslaved Alshari people to power this newly profitable mining. Transportation systems were developed for the mining infrastructure, and population boomed from Levantine immigrants seeking to take part in gold and diamond mining. Demand for enslaved Audonian did not wane after the decline of the mining industry in the second half of the 18th century. Cattle ranching and foodstuff production proliferated after the population growth, both of which relied heavily on slave labor. 1.7 million slaves were imported to Pelaxia from Daxia from 1700 to 1800. | |||

==Military== | |||

==Culture== | |||

==Science and literature== | |||

==Art and music== | |||

==Architecture== | |||

==Demographics== | |||

==Religion== | |||

==Languages== | |||

==Legacy== | |||

==Notable people== | |||

==See also== | |||

[[Category:Historical countries]] | [[Category:Historical countries]] | ||

[[Category:History]] | [[Category:History]] | ||

| Line 112: | Line 173: | ||

[[Category:Sarpedon]] | [[Category:Sarpedon]] | ||

[[Category:IXWB]] | [[Category:IXWB]] | ||

{{Template:Award winning article}} | |||

[[Category:2024 Award winning pages]] | |||

Latest revision as of 08:21, 11 March 2025

Westlands Republic of the Two Nations República de las Dos Naciones de las Tierras Occidentales (Pelaxian) República das Duas Nações das Terras Ocidentais (Cartadanian) Res Publica Utriusque Nationis Terras Occidentales (Latin) | |

|---|---|

| 1632-1795 | |

Motto: "Vinculum Liberorum et Fidelium" (Bond of the Free and Loyal) | |

Anthem: None | |

| Capital and largest city | Albalitor |

| Official languages | |

| Common languages | |

| Religion | Catholicism (official) Imperial Catholicism Protestantism Judaism Islam |

| Demonym(s) | Pelaxian Cartadanian |

| Government | Federal parliamentary elective monarchy

|

| Emperor | |

• 1632-1661 | Jeronimo I & III |

• 1661-1699 | Sebastian I |

• 1699-1723 | Sebastian II |

• 1723-1773 | None (Interregnum) |

• 1773-1795 | Felipe I |

| High Commissioner (Pelaxia) | |

| High Commissioner (Cartadania; pre-1710) President (Cartadania; post-1710) | |

| Legislature | Royal Courts |

| Supreme Court | |

| Grand Court General Court | |

| Formation | |

| 1632 | |

• De Pardo line extinguished | 1723 |

• First Calamity | 1772 |

• Girojons enthroned | 1773 |

• Second Calamity | 1793 |

• Third Calamity | 1795 |

| Currency | Old Real |

The Carto-Pelaxian Commonwealth, formally known as the Westlands Republic of the Two Nations and often referred to as Carto-Pelaxia, the Pelaxian Empire, or simply as the Kindreds Republic, was a federative real union between the Kingdom of Pelaxia and the Caridon Federal Republic, which became the Federative Republic of Cartadania after the Luso Rebellion of 1710, that existed from the enactment of the Union of Alahuela in 1632 until its dissolution after the Third Calamity in 1795. This state represents the House de Pardo at its zenith and was among the largest and most populous countries in 17th-to-18th-Century Sarpedon. At its largest territorial extent, during the reign of Emperor Sebastian II, the Commonwealth covered nearly one million square kilometres, or about four-hundred thousand square miles, in territory and sustained a vast, multi-ethnic population of about twenty-two million subjects. It was an officially trilingual state with its official languages being Pelaxian, Cartadanian, and Latin.

Carto-Pelaxia was formed in July of 1632 with the signing and enactment of the Union of Alahuela by the aristocracies of Pelaxia and Caridonia which had liberated their respective lands from Caphiria as a result of religious disagreements which had emerged due to the Great Schism of 1615 and the subsequent establishment of the Imperial Church of Caphiria. Pelaxia was the first country to revolt against Caphirian rule in the early 1620s, followed by Caridonia at around the same time, with the former greatly aiding in the latter's fight for independence. Due to the starkly different political cultures of the two newly-independent nations, the resulting state that had emerged carried elements of both monarchism and republicanism in an effort to please both nations.

The Commonwealth had possessed numerous features that were, and often still are, considered unique amongst contemporary and modern states. There was a strict system of checks and balances upon the Emperor which were enforced by the tricameral Royal Courts which consisted of the Supreme Court, which was a privy council that consisted of senior government officials and members of the clergy, the Grand Court, which consisted of junior government officials and members of the clergy, and the General Court, which consisted of the nascent merchant class and generals of the armed forces. The Royal Courts also had the responsibility to elect a new Emperor from the House de Pardo should the previous one pass away, though ultimately only the Supreme and Grand Courts held sway over the election, with the General Court holding only purely advisory powers. This system of government has served as a precursor to modern constitutional monarchy and liberal democracy due to its high enfranchisement. Constitutionally, the nations of the Commonwealth were supposed to be equal, but in actuality successive Emperors have more often than not favoured Cartadania (Caridonia pre-1710) despite it being officially a republic.

The overall multi-ethnic makeup of the Commonwealth gave it a high level of ethnic and religious tolerance as was guaranteed by the Constitution of the Two Crowns. Pelaxianisation and caridonisation (cartadanisation) and conversions to Catholicism were voluntary throughout the Commonwealth's history despite the Catholic Church holding official status.

After nearly a century of prosperity and stability, the Commonwealth would enter a period of rapid decline with the sudden death of Emperor Sebastian II in 1723 without any living relatives, thus extinguishing the de Pardo lineage. Because there was no provisions to elect a new royal house in the event that the de Pardo line died off, the Royal Courts decided to govern the country without an Emperor and thus entered into a fifty-year-long interregnum period, effectively becoming an aristocratic republic. Without a royal figurehead to keep the nobility more or less in line, the inherent flaws of the Carto-Pelaxian system began to emerge. Although semi-democratic, there were no formal political factions or parties which meant that the enfranchised nobility, which went up well into the hundreds, were largely independent from one another. This became especially egregious whenever legislative or executive actions were put up to a vote as legislation that had a clear majority of support were often killed by a single noble who would constantly add on frivolous and often unpopular amendments, things that would have been vetoed by the Emperor, which would either stall the passage of the proposed legislature or even defeat it outright. As a result, the Commonwealth quickly became unstable with its enemies more than eager to take advantage.

The chaos and lack of significant progress during the interregnum would culminate in the First Calamity in 1772 when the Commonwealth lost territories to a resurgent Caphiria and neighbouring Slavic realms. The traumatic loss would finally force the Royal and Grand Courts to finally elect a new Emperor, hastily electing Emperor Felipe I of the House of Girojon. However, the election of Felipe I failed to keep the Commonwealth from collapsing. The Second Calamity in 1793 saw even further southern lands being lost as well as a viral outbreak which eliminated three-quarters of the nobility that further plunged the realm into instability. Despite various reforms being passed in an effort to rationalise the overly complicated political system, the Third Calamity in 1795 would see Carto-Pelaxia dissolve with the Girojon monarchy, now demoted to a royal family instead of an imperial family, retaining control over Pelaxia and the republican government retaining control over Cartadania. The lingering trauma from the collapse of the Commonwealth would serve as one of the causes behind the Pelaxian Revolution in 1803 and the establishment of the First Pelaxian Republic.

Name

The official name of the state was the United Kingdom of Cartadania and Pelaxia (Cartadanian: Reino Unido de Cartadania e Pelaxia, Pelaxian: Reino Unido de Cartadania y Pelaxia, Latin: Regnum Unitum Cartadanium Pelagium) and the Latin term was usually used in international treaties and diplomacy.

In the 17th century and later it was also known as the 'Most Serene Commonwealth of Carto-Pelaxia'.

Levantines often simplified the name to 'Cartopelaxia' and in most past and modern sources it is referred to as the Kingdom of Pelaxia, or just Pelaxidania.The terms 'Commonwealth of Cartadania and Pelaxia' and 'Commonwealth of Two Nations' were used in the Reciprocal Guarantee of Two Nations.

Other informal names include the 'Republic of Nobles' and the 'First Commonwealth of Sarpedon.'

History

Prelude (1283–1618)

The Province of Pelaxia and the Province of Cartadania underwent an alternating series of wars and alliances across the 13th and 14th centuries. The relations between the two states differed at times as each strived and competed for political, economic or military dominance of the region. In turn, Pelaxia had remained a staunch ally of its northern ruler, Caphiria.

The Treaty of Agrila of 943 assigned the western part of modern Pelaxia to the House of Castrillón, ruled by Luciano II, and the eastern part to the eastern Agrilan Duke of Agrila. During the 12th century the counts of Santialche, vassals of Adolfo Duke of Agrila, founded many cities, the most important being Alimoche in 1120, Fatides in 1157, and Barcegas in 1191. The Santialche dynasty ended with the death of Balbino in 1218, and their cities subsequently thus became independent, while the dukes of Kazofort competed with the Albalitorian Warden house of Castrillón over control of the rural regions of the former Santialche territory.

The rise of the Castrillón dynasty gained momentum when their main local competitor, the Kazofort dynasty, died out and they could thus bring much of the territory south of the Rayado River under their control. Subsequently, they managed within only a few generations to extend their influence through Savria in south-eastern regions. Under the Horiz rule, the Picos passes in Montia and the San Alberto Pass gained importance. Especially the latter became an important direct route through the mountains. The construction of the "Devil’s Bridge" (Puente del Diablo) across the Picos Centrales in 1198 led to a marked increase in traffic on the mule track over the pass. While some of the "Free Communities" (Comunidades Libres, i.e. Montia, Cevedo, and Bajofort) were Imperolibertos the Castrillón still claimed authority over some villages and much of the surrounding land. While Cevedo was Imperoliberti in 1240, the castle of Nueva Brine was built in 1244 to help control Lake Lucrecia and restrict the neighboring Forest Communities. In 1273 the rights to the Comunidades were sold by a cadet branch of the Habsburgs to the head of the family, Laín II. Laín II was therefore the ruler of all the Imperoliberti communities as well as the lands that he ruled as a Castrillón

Laín II instituted a strict rule in his homelands and raised the taxes tremendously to finance wars and further territorial acquisitions. As king, he finally had also become the direct liege lord of the Comunidades Libres, which thus saw their previous independence curtailed. On the April 16, 1291 Laín bought all the rights over the town of Lucrecia and the abbey estates in Bajofort from Abbey. The Comunidades saw their trade route over Lake Lucrecia cut off and feared losing their independence. When Laín died on July 15, 1291 the Comunidades prepared to defend themselves. On August 1, 1291 a League was made between the Comunidades Libres for mutual defense against a common enemy.

With the opening of the Gastian Pass in the 13th century, the territory of Central Pelaxia, primarily the valleys of Montia, had gained great strategical importance and was granted Imperoliberti by the Horiz monarchs of Agrila. This became the nucleus of the Montian Confederacy, which during the 1330s to 1350s grew to incorporate its core of "eleven provinces"

The 14th century in the territory of modern Pelaxia was a time of transition from the old feudal order administrated by regional families of lower nobility (such as the houses of Babafort, Estreniche, Fegona, Fatides, Foronafort, Gouganaca, Huega, Tolefe, Terrafort, Rimiranol, Tarabefort, Santialche etc.) and the development of the powers of the late medieval period, primarily the first stage of the meteoric rise of the House of Castrillón, which was confronted with rivals in Agrila and Sebardoba. The free imperial cities, prince-bishoprics and monasteries were forced to look for allies in this unstable climate, and entered a series of pacts. Thus, the multi-polar order of the feudalism of the High Middle Ages, while still visible in documents of the first half of the 14th century such as the Codex Manesse or the Montia armorial gradually gave way to the politics of the Late Middle Ages, with the Montian Confederacy wedged between Castrillón Pelaxia, the Kingdom of Agrila, the Duchy of Sebardoba and the Duchy of Ficetia. Babafort had taken an unfortunate stand against Castrillón in the battle of Scafaleno in 1289, but recovered enough to confront Fatides and then to inflict a decisive defeat on a coalition force of Castrillón, Sebardoba and Abubilla in the battle of Lupita in 1339. At the same time, Castrillón attempted to gain influence over the cities of Lucrecia and Zaralava, with riots or attempted coups reported for the years 1343 and 1350 respectively. This situation led the cities of Lucrecia, Zaralva and Babafort to attach themselves to the Montian Confederacy in 1332, 1351, and 1353 respectively.

The catastrophic 1356 Abubilla earthquake which devastated a wide region, and the city of Abubilla was destroyed almost completely in the ensuing fire. The balance of power remained precarious during the 1350s to 1380s, with Castrillón trying to regain lost influence; Alberto II besieged Zaralva unsuccessfully, but imposed an unfavourable peace on the city in the treaty of Reifort. In 1375, Castrillón tried to regain control over the Savria with the help of Caphiric mercenaries. After a number of minor clashes, it was with the decisive Confederated victory at the battle of Campes in 1386 that this situation was resolved. Castrillón moved its focus westward and lost all possessions in its ancestral territory with the Confederated annexation of Brine in 1416, from which time the Montian Confederacy stood for the first time as a political entity controlling a contiguous territory. Meanwhile, in Abubilla, the citizenry was also divided into a pro-Castro and an anti-Castro faction.

In 1485, the Union of Termia was signed between Reginaldo Castrillón of Alabalitoria and Jerónimo De Pardo, the Grand Duke of Agrila, the Head Chancellor of the Montian Confederacy. The act arranged for Reignaldo's daughter Josefina to marry Jerónimo, which established the beginning of the Pelaxian Kingdom. The union strengthened both regions as self appointed protectors of Pelaxia, in their shared opposition to the newly formed Kingdom of Savria under King Didac l, self-appointed protector of the south.

The intention of the union was to create a common state under Albalitorian law, with the support of the ruling oligarchy in the Montian Confederacy. Castrillón would gain access to the trade passes through the Picos into the Dominate of Caphiria, while the Confederates would gain access to Albalitorian ports and sea routes. Thus, in the Jeronimian period, Pelaxia developed as a feudal state with a predominantly agricultural economy and an increasingly dominant mercantile nobility.

Union of Alahuela (1632)

-

Emperor Jerónimo III, Despote of Pelaxia and Cartadania, King of Savria and Lord Protector of the Jusonias.

-

Braçayda de Fonseca, Plenipentontial Minister of the States of Cartadania

-

Hipólito Francisco de Huerva, Royal Chancellor of Pelaxia.

Apex and the Golden Age (1673–1723)

Kindred Wars

Interregnum (1723–1772)

First Calamity and Girojons enthroned (1772-1773)

Further calamities (1773–1795)

State organization and politics

Magnate oligarchy

Late reforms

Economy

The economy of the Commonwealth was predominantly based on agricultural output and overseas trade through the southern route into Audonia, though there was an abundance of artisan workshops and manufactories — notably paper mills, leather tanneries, ironworks, glassworks and brickyards. Some major cities were home to craftsmen, jewellers and clockmakers. |

The majority of industries and trades were concentrated in the Kingdom of Pelaxia; the Republic of Cartadania was more rural and its economy was driven by farming and clothmaking. Mining developed in the north-east region of Pelaxia which was rich in natural resources such as lead, coal, copper, iron ore, gold. The currency used in Carto-Pelaxia was the (xxxx) and its subunit, the (xxxx) Foreign coins in the form of (xxxxx) were widely accepted and exchanged.

The country played a significant role in the supply of Levantia and Caphiria by the export of grain (rye), cattle (oxen), exotic fruits, furs, timber, linen, coffee, peanuts, coconut oil, palm oil, poultry meat, corn and cotton. Cereals, coffee, cattle and fur amounted to nearly 90% of the country's exports to Levantine markets by maritime trade in the 16th century. From Albalitor, ships carried cargo to the major ports of the (XXXX), such as (XXXX) and (XXXXX).The land routes, mostly to the Caphirian provinces of the such as the cities of (XXXXX) and (XXXXX), were used for the export of live cattle (herds of around 50,000 head) hides, salt, tobacco, hemp and cotton from the Cartadania. In turn, the Commonwealth imported wine, beer, fruit, luxury goods (e.g. tapestries), furniture, fabrics as well as industrial products like steel and tools. Much of the product variety and commercial capacity of the Commonwealth was deeply dependent on the trade with Audonia through the southern route. Most of the Commonwealth production is exclusively based on slave labor supplied by Daxian traders in special enclaves in the far east continent.

The slave system was inherited from the Caphiric socio-economic structure of the Carto-Pelaxian provinces. Though much of it has had extensive reforms from the local nobility through the drafting of feudal law codes that evolved slavery into serf status regimes especially associated with a noble. The increasing demands for tropical products from the Levantine economies increased the need for efficient and cheap labor, which was quickly supplemented through the dominance of overseas territories such as Vallos or trade with Daxia.

Slave labor was the driving force behind the growth of the sugar and coffee economy in Carto-Pelaxia, and coffee was the primary export of the Cartadania from 1600 to 1650. Gold and diamond deposits were discovered in Pelaxia in 1690, which sparked an increase in the importation of enslaved Alshari people to power this newly profitable mining. Transportation systems were developed for the mining infrastructure, and population boomed from Levantine immigrants seeking to take part in gold and diamond mining. Demand for enslaved Audonian did not wane after the decline of the mining industry in the second half of the 18th century. Cattle ranching and foodstuff production proliferated after the population growth, both of which relied heavily on slave labor. 1.7 million slaves were imported to Pelaxia from Daxia from 1700 to 1800.

Military

Culture

Science and literature

Art and music

Architecture

Demographics

Religion

Languages

Legacy

Notable people

See also