Arco Polar Expeditions: Difference between revisions

m Text replacement - "Category: 2022 Award winning pages" to "{{Template:Award winning article}} Category:2022 Award winning pages Category:IXWB" |

|||

| (2 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

[[category:Arcerion]] | [[category:Arcerion]] | ||

[[Category:IXWB]] | [[Category:IXWB]] | ||

[[Category: Award winning pages]] | {{Template:Award winning article}} | ||

[[Category:2022 Award winning pages]] | |||

[[Category:IXWB]] | |||

[[Category:Arcer History]] | |||

Latest revision as of 10:30, 10 August 2023

The history of Arco Polar Expeditions was a period spanning from 1891-1918 (27 years) during which the Arctic was explored by different Arcer explorers. This period was a massive expansion of Arcer naval influence outside of the Malentine and Songun Seas, and much of these travels were sponsored by the Arcerion Naval Service as part of its ongoing efforts to expand its ability to conduct blue-water operations.

During this time period, the Arctic became the focus as it held a great amount of scientific and geographical importance to the Arcer community. As most of Crona was Indigenous, there was few maritime-based opportunities for Acers to explore or venture beyond the South Cronan Peninsula. Therefore, with the initial state-sponsored expedition of 1891, Arcer explorers, navigators, geographers, and officers ventured North through the Odoneru to stake their claim to the frozen expanses of the Arctic Circle. There was 10 major expeditions, although smaller, privately-funded ones also occurred throughout this period but were not as intensely logged or chronicled.

The primary focus of many of the early expeditions were the use of new or novel technologies that expanded the limits of human endurance and physical stamina due to the exceedingly harsh conditions. As well, the Arco climate, mostly plains and warm in nature, did not immediately outfit or set up the explorers for success, and the initial exposure/frostbite casualties of the 1891 and 1893 expeditions reflect this. Although official estimates vary between public and private sources, somewhere between two and three dozen Arcers died during these forays North.

The expeditions also claimed several important achievements for Arcerion, notably being the first nation to have a citizen reach the North Pole, both geographic and magnetic. Previously, nomadic indigenous locals were assumed to have reached it, this was the first time a modern nation state had achieved the accomplishment. Additionally, much of the Arctic coastline was mapped during the first three expeditions, with John Howland's expedition accomplishing not only the survey task, but also the successful mission to the North Pole. The expeditions all generated a fair amount of scientific data for the greater Cronan scientific community, much of which became a focal point for inviting Arcer explorers and scientists to Levantia and Sarpedon for conferences and university tours to give lectures and share results with newer explorers.

Origins

Expeditions 1891-1918

Expedition of 1891

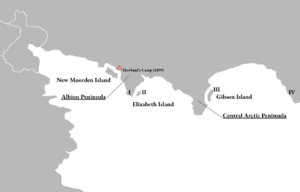

This was the first expedition undertaken by Arcerion to the Arctic, leaving in February of 1891 from the Songun port of Chester-on-Moore, the voyage not being entirely completed until late 1892. Led by Walter Hetherington, assisted by the soon-to-be-famous John Howland, it was primarily aimed at an initial survey and geographic mapping of the Arctic peninsulas to the East of Northern Crona, jutting out into the Albion Sea. During this expedition, Hetherington and Howland performed the first full oceanographic and coastal surveys of the Northern Albion Sea. It also discovered two islands Elizabeth Island and Gibson Island. Elizabeth Island, named for Hetherington's first daughter, was discovered during the initial entrance into the Northern reaches of the Albion Sea. Gibson Island was named after a member of the expedition who died after succumbing to cold-weather exposure injuries sustained while exploring the island. During the 1891 expedition, four separate landings and explorations were made by John Howland, the two aforementioned islands, as well as a pair of shore trips onto two separate peninsulas. The expeditions themselves were marked by harsh conditions due to the Arctic weather.

The government sponsored expeditionary research in much of the Cronan Interior for safari-style forays into the continent, however serious maritime navigational exercises and missions had not been accomplished at this point by any Cronan nations. As such, the government contacted the Geography and Survey Department at the Carnish Anglican University in Kurst, Arcerion for a proposal on how they could feasibly explore the Arctic Circle. The head of the department at the time, Walter Hetherington, began recruiting from several sources. Scientific expertise was acquired from the university as well as several architecture and engineering firms in Kinnaird and Kurst. For experience in colder climates and experts on mountaineering and long-distance patrolling, he requested volunteers from Chester Fusliers and Arcerion Easthampton Borderers, a pair of infantry regiments that had particular expertise fighting rebel and guerilla forces in Arcerion's Southeastern mountains. Of these was a former Captain with the Easthampton Borderers, John Howland, By far the most important selection however was the maritime and naval experience, of which Arcerion had limited beyond the Malentine and Songun Seas. Several merchantmen saw profitable opportunities, and career naval officers themselves saw this as a way to stake their claim and make their mark in the annals of the Arcerion Naval Service. As such, dozens of sailors and seamen from Chester-on-Moore and Kurst volunteered for the task. With the personnel assembled and beginning preparations in Chester-on-Moore, the government purchased a pair of sailing ships had to be procured. The Navy had no suitable ships for cold-weather sailing, and as such a pair of ships that had already been commissioned for the Navy were retrofitted during the construction and converted to Arctic exploration vessels. The three-masted Barquentines, named Chester and Emily, would each host a compliment of forty men and the requisite supplies for travel to the Arctic circle. Training and supplies continued to be procured and conducted until February of 1891, when the expedition set off. With an initial stop in Cape Town, the expedition then set off for the Kiravian port of Sirana, following this with a resupply stop in the Republic of New Archduchy. By this point, the journey had been ongoing for several months, with the final pre-Arctic resupply stop made at the Kiravian colony of Xepramonta. Arrival approximately three months after they had set out for the journey, the two ships first sighted the Arctic Coast on the 2nd of May, 1891. With average temperatures at night around -10°C, and during the day around 5°C, the ships were frequently coated with ice. Considering the average temperature in Arcerion at its coldest is roughly the same, many of the more experienced mountaineers found this familiar, but the sailors on the Malentine and Songun Seas had not thus experienced temperatures like this so far. The first foray ashore was made by John Howland on the 6th of May, 1891 and conducted initial surveys and took some rock and soil samples. He was accompanied by three members of the Emily's crew, one of who would later perish due to exposure injuries sustained later in the expedition.

After the Albion Peninsula expedition, which lasted several days, the Chester and Emily both set off to what Hetherington would name Elizabeth Island. On Elizabeth Island, Howland found some signs of human life in the form of rock sculptures and carvings into the rocks on the Northern shore, and the limited cave exploration in the area, and assessed it was from some of the first Indigenous peoples that would have migrated to Crona during the pre-historic era. Upon preparations to leave Elizabeth Island, the Emily struck an iceberg and required repairs, and the crews remained moored off the North Shore for an extra four days while the sailors repaired the damaged hull enough to permit continuing travel.

Setting off at the end of May, the expedition made it around another peninsula and discovered another island. It was here that Nathan Gibson would become the first Arcer to die in the Arctic. John Howland again led an expedition ashore onto the island, but on their second night a snowstorm destroyed much of their camp and supplies. Over a day's travel away from the moored ships, they struggled back across rocky and snow-swept terrain back to the Chester, many of the members suffering from frostbite and hypothermia. Nathan Gibson passed away the next day, which greatly affected morale. Walter Hetherington named the island in his honour, and they conducted a burial on the shore nearby, the gravesite which is still there to this day, constructed of local rocks and with a large cross hewn out of stone and secured with rope. The expedition continued, moving across the sea to the final part of the coastline where they sent another shore party for a longer stint, Howland leading one of two parties, both returning within a week to the coast to be recovered.

The expedition concluded as the ships sailed South, successful in their voyage despite the loss of one of their members. They made the same ports of call upon their return, and upon their return to Arcerion, stopped for brief respite in Chester-on-Moore before a receiving parade in Kurst. The scientific data and navigational charts were methodically studied and used to plan the expedition of 1893, which was again to be led by Walter Hetherington. The impact culturally was incredibly significant. Walter Hentherington and John Howland became household names in Arcerion, and the Carnish Royal Family send a letter of congratulations to the Arcer Parliament congratulating the nation on its expedition, even going so far as extending the invitation to Hetherington to visit Carna to be received by the Crown Regent.

Expedition of 1893

Capitalizing on the success of the 1891 expedition, the Confederate Parliament authorized the raising of a second expedition to take place the following year. Preparations however, were considerably more rushed and this would result in catastrophe. The schooner Emily, still not fully repaired, was not chosen to again participate as one of the ships in the expedition. Chester was to be accompanied a new schooner, Forthright, as well as one of the Naval Service's new frigates, Archer. The Navy was keen on testing the frigate's ability to operate far beyond the Songun as if this was successful it could use it as precedent for additional ships to be constructed. The ships finished preparations not even a full year after the 1891 expedition's return, departing in the summer of 1893.

They followed a similar route, making resupply stops at ports of call in the Cape, Kiravian colonies, and the New Archuchy, but instead of focusing on the Northern Albion Sea, the expedition intended to head farther East, closer to Kiravia, as this stretch of coastline had limited survey and geographical assessments done by even the Kiravians. The main miscalculation here was the poor lack of accountability for the weather's impact. Previosuly, the departure with the turn of Spring in the Northern Hemisphere meant that the temperature was more permissive to the explorers upon their arrival in April/May of 1891. For this expedition however, the summer departure as well as farther distance meant that the October/November arrival brought with it considerable storms and seas which the Forthright struggled in. After a storm in October South of Gibson Island whilst transiting Eastwards, the Forthright lost a mast, its fall crushing two members to death. The loss in propulsion and confusion during the storm required a stop, not too far from the fourth landing in the 1891 expedition, until the mast could be repaired. The hard seas and this delay mean that the expedition arrived at their survey locations in mid-November. With the daily average temperature around -10°C. Only two landings were conducted, one by Hetherington himself for three days, and a second, longer expedition by Howland for nine days. During this time Howland made use of his previous military experience to lead a dozen men the furthest inland at that point that any non-indigenous person had ever went into the Arctic. Using sleds and snowshoes, they made it 46km inland before reaching a halfway point they determined was sufficient and heading back to the Chester. By this point on the return, the late November temperatures began coating the ships rigging and superstructures with a considerable amount of ice. A lack of de-icing equipment, as well as many of the new volunteers who were not veterans of the 1891 expedition lacking proper winter clothing meant that problems stemming from the initial rush for another successful expedition began to be seen. Disaster struck during another winter storm off the coast of the Albion Peninsula in the last week of November, 1893. Severe icing on the Forthright's rigging had caused her to become overly top heavy. Howland, then leading the land expeditionary contingent on the Archer, as the Emily was undergoing repairs, watched as the Forthright took on a serious list to starboard, and took on water. With waves as high as 25 feet, the ship went under shortly after, with no ability to launch lifeboats, life rafts, etc. The heavy sea state and freezing conditions above and below surface meant that the ability to rescue survivors, if any, was limited. This represented the first serious loss of life on an expedition, the Forthright having 27 souls aboard when she sank.

The return to Arcerion was considerably less enthusiastic as the brave adventurers had lost so many of their own, and the government was incredibly hesitant to now continue funding these expeditions. However the Arco Transpolar Investigatory Commission was setup by the Foreign Office in conjunction with the Naval Service to investigate the sinking of the Forthright, and found that rushed preparations, poorly trained and equipped crew, and a lack of experienced Arctic sailors had led to the demise of the Forthright. However, from this, the government began to work on codifying the requirements for future expeditions should the appetite arise again, and recommended that much more time and effort be invested into future expeditions in order to minimize unnecessary loss of life. Hetherington, in his memoirs, stated that the loss of the Forthright was entirely preventable, and only a mad frenzy to foster another successful expedition had led to the deaths of almost thirty men.

Expedition of 1899

After the loss of the Forthright in 1893, John Howland had been determined to take another expedition North and set up a long-term survey and research camp dedicated to providing that Arctic expeditions were still feasible. Howland entreated the Arco Transpolar Investigatory Commission twice unsuccessfully, in both 1894, and 1896 for a new expedition of this sort to be made. Finally, the decision was made to permit the sailing of a single ship and crew to minimize the fallout should it be lost after the Forthright loss. Howland during this time had kept up his academic research and preparations, leading a pair of mountaineering expeditions to Mount Carter in Moorden in 1895 and 1896. From this, he had cultivated an experienced team of civilian and military explorers. However, with the turn of the century and a renewed effort to cement Arco national identity, Prime Minister Daniel Hayes approved a limited expedition of a single ship to the Arctic, with the caveat it was led by Howland and was comprised of experienced volunteers. Concurrent to this, oversight from the Arco Transpolar Investigatory Commission for preparation based off of their 1893 report on the previous expedition's shortcomings and failures leading to disaster were mandated.

Howland accepted the terms and in the summer of 1897 began a two-year plan to prepare his teams for what they would experience. He recruited his land contingent from not only the mountaineers and alpine experts of Moorden, but he specifically targeted his maritime and naval contingent from a mixture of 1891/93 veteran sailors, augmenting them with whalers from Burgundie as best he could. Howland felt they brought rough sea experience that was lacking in 1893, that would make the difference for the longer, more difficult expedition of 1899. The maritime contingent specifically focused on sailing in rough seas, going through drills, procedures, and contingencies that would help them excel. In this instance, a twin Arco-Burgoignesc pair would set the conditions for a successful maritime navigation to the Arctic. Douglas Shaw, and Ensign of 28 and descendant of a blockade runner from the Cronan Beaver Wars, he had made a name for himself in the Navy for his emphasis on what would eventually become known as "blue-water" (open sea) operations. He had taken a small sloop from Chester-on-Moore, and in 1894 sailed to the Pelaxian capital of Albalitor in record time, and the first time an Arcer sailor had done this with only a two-masted sloop made for Songun Sea travels exclusively. Shaw would be complemented by Lucien Boissieu, a whaler from Burgundie who had recently travelled to the New Archduchy to begin whaling in the Odoneru Ocean. His experience with the type of long-distance, expeditionary sailing, combined with Shaw's emphasis on preparation and robust training combined to create a solid naval complement for the journey.

Howland tasked both Shaw and Boissieu together to find a ship suitable for the journey. In this instance, they found in the port of Kinnaird the Defiance, a three-masted schooner, that was being refit as a whaler. Upon a petition by the Arcer government, it was purchased for £19,000 Arcer Pounds and sailed to Chester-on-Moore to undergo retrofitting for Polar exploration in 1888. The land contingent procured sleds, cold-weather clothing, and the requisite equipment they would need for an extended stay on the Arctic shores. In January of 1899, the Defiance left the port of Chester-on-Moore. With a complement of fifty six, it had nearly half a complement more than it had been designed for, and living conditions were increasingly cramped. However, between Howland, Shaw, and Boissieu, the voyage North was made in record time, and they arrived in the Albion Sea after roughly two and a half months travel, skipping the Cape's port and transiting the Songun Straits without the need for a resupply stop.

The search began for an initial place from where to encamp and begin their surveys, studies, and observations in the Arctic. Secondary to this, Howland had begun to prepare for a petition to the Arcer Parliament for a longer expedition that would permit a single team to make the trip to the North Pole. Howland at this time discovered a new island, previously unmapped and what many had thought to be part of the Arctic mainland. New Moorden Island, the Westernmost of the three Arctic Albion Islands, was also the largest, and there was a brief two day expedition led by Howland inland while Shaw and Boissieu undertook necessary repairs and maintenance on the Defiance. On New Moorden, the highest point allowed Howland to gain a good vantage point, and from there using his telescope and survey equipment he was able to identify suitable future spots for expeditions on the island, as well as a small deep-water inlet he believed could serve as the basis for a future Carnish or Arco colony. Returning to the ship's company, they departed late April and arrived at the mainland shore, from where Howland set up their permanent encampment for the next months. The weather by now, in the summer, was far more permissible, but they knew they were in for a long tenure. By day, temperatures remained around 10°C, but at night they dropped just below zero. The warmest day recorded was in the last week of June with a daily high of 19°C. During the day, small expeditions and forays inland were made to try and discover new sights and conduct additional land and coastal surveys. A pair of biologists from the Carnish Anglican University also catalogued at least three species of bird, and several small land mammals, such as hares and marmots. The sailors themselves assisted with the aquatic portion of this, working with the scientists to fish and trap sea life on the shore, which also provided them with activities outside of the maintenance and repair of the Defiance and their camp routines. Inland, a pair of infantrymen from the Easthampton Borderers sighted the first large land mammal in the Arctic that an Arcerion expedition had seen, the Albion Wolf. Credited with the first successful hunt of one, LCpl Hamish Bailey, with 'G' Company, 3rd Battalion, the Arcerion Easthampton Borderers was noted to have shot it with a trapdoor rifle at a distance of approximately 320 yards. Its pelt is still on display in the Sergeant's and Warrant Officer's Mess at the Easthampton Garrison.

By late September, the weather had begun to turn and plans for the journey home began to solidify. Scientists were told that by New Year's Day, the Defiance would be setting sail to return to Arcerion. With final expeditions and samples taken, the scientific contingent was ready to go by Christmas Day 1899, on which the entire expedition's complement enjoyed salted fish, brandy, and marmot jerky with dried cranberries. Shaw and Boissieu set the departure date for December 29th based off of the limited weather data they had, and the expedition left Howland's Camp that morning.

The return faced a trio of brutal storms, the first keeping them in New Moorden Channel for several days, and once they had survived that and made it to the tip of the Albion Peninsula another forced them to shore where they moored near the site of Howland's first shore trip from 1891, eight years prior. The final storm caught them in open seas as they transited South back towards Crona, at one point nearly washing Shaw overboard, had he not been saved by a member of the ship's science company who grabbed him and held him on.

They arrived back in February of 1900, the expedition a resounding success. The scientific data gleaned, survey and navigational charts produced, as well as the prestige of the longest Arctic expedition to date a the cost of no lives lost heralded in a new era of government confidence in the journeys Northwards. Howland was lauded with scientific and exploratory awards, and his naval subordinates, Shaw and Boissieu each received service medals (Boissieu's an honorary one due to his civilian status). The Arco Transpolar Investigatory Commission report commended the expedition as one of the finest moments of Arcerion national achievement, and recommended that Howland be allowed to conduct additional, more lengthy expeditions in the future. Howland, who now felt he had to momentum and popular backing, petitioned Parliament in April of 1900 for a North Pole Expedition, and Parliament approved, giving him a discretionary budget of £250,000 to finance and fund the effort.

Howland's Expedition

Easthampton and Leo

In late April of 1900 Howland met with Ensign (is this still his rank?) Douglas Shaw and the Burgoignesc Captain Lucien Boissieu to discuss the particulars of outfitting a ship for this next expedition. The list was broad and encompassed: flexibility to handle the high seas, rigidity to handle the pack ice, a vast amount of storage (for both a commissary and the expeditionary equipment), and accommodations for the crew and pack animals. In the summer of 1900, Shaw and Boissieu set out on an expedition to find a pair of ships that would meet these new specifications. They were unsuccessful, specifically in their attempts to find a ship in the equatorial waters that was at the same time flexible and rigid. They reported back in the early autumn and requested to be dispatched further afield. They were given a small stipend and give another 6 months to find a ship that met all of the specifications. After a series of meetings across the Odoneru it became clear such a ship did not exist and would have to be built. Boissieu convinced Shaw to go to Burgundie and meet with the draughtsmen at Chantiers d'Aristide who specialized in high-endurance whaling and clipper ships. They arrived in early December and laid out their specifications. The draughtsmen worked for three weeks on the design. At one point Shaw became fed up with the waiting and the speed at which Boissieu was burning through their stipend that he began preparations to return.

The plans were for a wooden-hulled Barquentine, made of oak, cross-braced at every joint and fitting, with keel members of 4 pieces of solid oak, one above the other, adding up to a thickness of 85 in (2,200 mm), while her sides were between 30 in (760 mm) and 18 in (460 mm) thick, with twice as many frames as normal and the frames being of double thickness. The ship was to be built of planks of oak and Wintergenesc fir up to 30 in (760 mm) thick, sheathed in greenheart, an exceptionally strong and heavy wood. The bow, which was designed to meet the ice head-on, had been given special attention. Each timber had been made from a single oak tree chosen for its shape so that its natural shape followed the curve of the ship's design. When put together, these pieces had a thickness of 52 in (1,300 mm). A 350 hp (260 kW) coal-fired steam engine, making the ship capable of speeds up to 10.2 kn (18.9 km/h; 11.7 mph) was also to be installed. It was to be the strongest wooden ship ever built. Shaw and Boissieu were elated but Chantiers d'Aristide wanted £50,000 per ship which was too much. They purchased the plans for £500 and returned home dejected, but glad that they had made progress.

Upon their return, in late January, they showed the plans to Howland who became set on having the ships built. He authorized Shaw to return (without Boissieu) with £50,000 and an order to come home with two ships or £50,000. Shaw was halfway back to Burgundie when he discovered Boissieu stowed away on board. After a few days of chastizement, he resolved himself to Boissieu's presence. Shaw evaded Boissieu at port (brought him to a bar) and made his way to Chantiers d'Aristide to negotiate terms. After a day and a half he was able to get the price for both ships down to £70,000 but no further. Boissieu had finally tracked down Shaw and, upon discovering the shortage, challenged the owner of Chantiers d'Aristide to a game of dice. The terms: both ships for £50,000 if he won, one ship for £70,000 if he lost. Shaw was beside himself with rage. The literal die was cast among the draughtsmen tables and chairs, and Boissieu won. The owner began to scream and yell and declare that Boissieu was a cheat. Boissieu calmly asked for the owner's set of dice, cast the die among the clutter of the workshop and once again won. The owner called for the gendarme's to arrest Boissieu for cheating at dice. Upon arrival Boissieu produced a pair of weighted dice that he claimed had come from the owner, and the draughtsman swore them to be the owner's dice. The matter was brought to the magistrate and the deal was ordered to be upheld.

Work began on the twin sister ships, Easthampton and Leo, the former being a reference to the many men who came from the Eastern Arcer mining town in the mountains, and the latter referencing the Red Lion, one of Arcerion's most prominent national symbols, inherited from the Kingdom of Carna.

Howland-Rickett Expedition

Expedition of 1911

Expedition of 1914

Towley Expedition

Austin-Taylor Expedition

Expedition of 1918

Deaths and Shipwrecks

Casualties

- Nathan Gibson, 26, Expedition of 1891. Exposure. Buried on Gibson Island.

- Lochlan Robinson, 22, Expedition of 1893. Crushed to death by a falling mast. Buried at Sea.

- Cayden Hall, 29, Expedition of 1893. Crushed to death by a falling mast. Buried at Sea.

Shipwrecks

- Forthright, Schooner. Expedition of 1893. Lost with all hands (27) in the Albion Sea.

Cultural Impact

Modern Arcer Arctic Expeditions