Agriculture in Great Kirav: Difference between revisions

m →Tinav |

|||

| (15 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

====''Allium''==== | ====''Allium''==== | ||

Vegetable crops belonging to the genus ''Allium'', such as {{wp|onion}}, {{wp|garlic}}, {{wp|scallion}}, {{wp|shallot}}, {{wp|leek}}, and {{wp|chives}}, are a highly important crop in Kiravian cuisine, and have been so since [[Prehistory of Great Kirav|prehistoric times]]. These crops are, as appropriate to each species, grown throughout the arable regions of Great Kirav. The most productive ''Allium''-growing regions, however, are [[Kaviska]], the interior plains surrounding the [[Lake Belt]], and [[Farravonia]]. Farravonia is also the main garlic, shallot, and chive-growing region. Under the traditional caste-based economy, most onion and leek production in the Kir-majority regions was undertaken by ethnic minorities, namely the [[Ĥeiran Coscivians|Kempans and Kyrnans]]. Leeks grow exceptionally well in the upper-middle latitudes of the continent on account of their preference for cooler climatic conditions. | |||

The artisanal gathering of {{wp|wild onions}} for soup and other cooking is still widely practised in rural Kirav, and as a hobby in suburban areas. | |||

===Hops=== | ===Hops=== | ||

| Line 100: | Line 103: | ||

Also [[sheep]]. | Also [[sheep]]. | ||

===Tinav=== | |||

The ''tinav'' is a {{wp|camelid}} similar to the {{wp|llama}}, {{wp|guanaco}}, or {{wp|alpaca}}. Its wild-type variant, no longer extant, was native to the alpine grasslands of West Kirav and was domesticated by the time of the Chalcolithic. Stock-raising of the ''tinav'' was a transformative event in Kiravian history, enabling the establishment of regular long-range overland trade networks and the geographic extension of political structures such as states and tribute networks. This made possible the Verticalist mode of production under the Emperald Emperors. In addition to its use as a draught animal, the ''tinav'' is raised for {{wp|wool}}, meat, and...maybe milk? | |||

The ''tinav'' has been used as a plough animal in certain marginal (mainly mountainous) lands where larger animals were unavailable or inappropriate. Its use for this purpose was more widespread before the introduction of oxen. | |||

===Swine=== | ===Swine=== | ||

[[File:Vildsvinssugga som boar.jpg|thumb|A pig foraging in the [[Trinatria]]n piedmont]] | [[File:Vildsvinssugga som boar.jpg|thumb|A pig foraging in the [[Trinatria]]n piedmont]] | ||

Suids were likely the first large mammals domesticated by prehistoric Kiravians. The Old Kiravian hog is a domestic variant of the native {{wp|Sus strozzi|Nearctic bearded boar}}, | Suids were likely the first large mammals domesticated by prehistoric Kiravians. The Old Kiravian hog is a domestic variant of the native {{wp|Sus strozzi|Nearctic bearded boar}}, which is likely extinct since the Kiravian Iron Age, though efforts to {{wp|Breeding back|breed back}} the Nearctic boar phenotype from Old Kiravian hogs are in progress. Modern swine stocks in Kiravia are generally of mixed ancestry, descending mainly from the Levanto-Sarpic common hog and with a substantial (though gradually declining) share of Nearctic boar heritage. Pure-bred Old Kiravian hogs are raised as a heritage breed, mostly by smaller farms as a specialty product. | ||

For most of recorded Kiravian history, swine were the primary source of meat. Pork and pork products remain the most widely consumed form of meat in the country (fish and fowl excluded), though beef has been steadily gaining ground since the end of Kirosocialism. The swine industry in Great Kirav has been steadily growing since the market reforms of the 1980s AD. Improved access to technology and capital has contributed greatly to this success. For example; Kiravian winters can be harsh, especially in the North and interior, and as such, many swine farmers have developed insulated and climate-controlled facilities to regulate indoor temperatures during extreme weather conditions.The construction of high-capacity climate-controlled swine shelters has greatly improved herd health and meat yields. Improved antibiotics and other inputs have similarly reduced losses and widened profit margins for farmers. | For most of recorded Kiravian history, swine were the primary source of meat. Pork and pork products remain the most widely consumed form of meat in the country (fish and fowl excluded), though beef has been steadily gaining ground since the end of Kirosocialism. The swine industry in Great Kirav has been steadily growing since the market reforms of the 1980s AD. Improved access to technology and capital has contributed greatly to this success. For example; Kiravian winters can be harsh, especially in the North and interior, and as such, many swine farmers have developed insulated and climate-controlled facilities to regulate indoor temperatures during extreme weather conditions.The construction of high-capacity climate-controlled swine shelters has greatly improved herd health and meat yields. Improved antibiotics and other inputs have similarly reduced losses and widened profit margins for farmers. | ||

| Line 112: | Line 121: | ||

===Cattle=== | ===Cattle=== | ||

[[File:Dende a Garita de Erbeira 02.JPG|thumb|'Farrvonian Blonde' cattle in Metrea]] | |||

The first attempt to introduce cattle to inland Kirav was made in 25XD4+2Q [[Coscivian calendar|CC]] by Oranibur Kaisthev, chancellor to the King of the Antarans. Kaisthev purchased some 400 head of Urcean longhorn cattle to increase the king’s revenues from montane pasturelands. However, upon their delivery to what is now County Upśur in [[Verakośa]], the cattle were immediately slaughtered by terrified locals, who recognised them as the Devil’s hounds. Subsequent attempts were foiled along the same lines. | The first attempt to introduce cattle to inland Kirav was made in 25XD4+2Q [[Coscivian calendar|CC]] by Oranibur Kaisthev, chancellor to the King of the Antarans. Kaisthev purchased some 400 head of Urcean longhorn cattle to increase the king’s revenues from montane pasturelands. However, upon their delivery to what is now County Upśur in [[Verakośa]], the cattle were immediately slaughtered by terrified locals, who recognised them as the Devil’s hounds. Subsequent attempts were foiled along the same lines. | ||

[[Korlēdan]] is the leading beef-producing state in Great Kirav. In recent years, beef enterprises in Korlēdan have been consolidating under a local affiliate of the [[Federation of Daxian Beef Producers]]. | A strong majority of cattle in Great Kirav are {{wp|dairy cattle}}. Dairying is an important activity in the Far Northeast, Upper Kirav (especially [[Vôtaska]], where dairy giant [[Banya Sēora SAK]] is based), and upland meadows of the Eastern Highlands and Central Massif. Since 2012 AD, most Kiravian dairy products are sold abroad with the assistance of the [[Kiravian Dairy Board]], and the industry as a whole is now increasingly re-gearing towards an export orientation. Dairy yields have greatly increased in the post-reunification era, while domestic demand remains constrained by the fact that only a minority (~28-36%) of Kiravians are {{wp|Lactase persistence|lactose-tolerant}}.<ref>Lactose tolerance is highest among the [[Celtic-Kiravians|Celtic-Kiravian]] and [[Levantine-Kiravians|Levantine-Kiravian]] minorities; among Coscivians it is highest in [[Ĥeiran Coscivians|Ĥeiran]] populations and is indicative of historical Levantine (mainly Celtic) admixture.</ref> | ||

[[File: | |||

Beef rearing is a smaller but nonetheless significant subsector of the livestock industry. From the introduction of cattle to the island continent until Kiravian reunification, most Kiravian beef was destined to be {{wp|Corned beef|corned}} or otherwise {{wp|Salt-cured meat|cured}}. Nationwide distribution of domestic fresh beef did not arise until after the end of Kirosocialism, under which all beef was requisitioned by the government to supply the Kiravian People's Army and supplement [[Kiravian_Union#Rations|the Social Ration]]. [[Korlēdan]] is the leading beef-producing state in Great Kirav. In recent years, beef enterprises in Korlēdan have been consolidating under a local affiliate of the [[Federation of Daxian Beef Producers]]. | |||

===Other Bovids=== | |||

[[File:Muskus.jpg|thumb|A muskox in [[Lataskia]] ]] | |||

Some communities native to the the {{wp|tundra}} areas of the North Coast, montane Northwest, and Ximantav Mountains have a tradition of herding {{wp|Muskox|muskoxen}}. It is believed that this practice originated in the northern highlands during the late Neolithic, when hunter-gatherers learned to drive the animals into small, dead-end {{wp|Hollow (landform)|hollows}} where herds could be contained and more easily harvested. Over time, practitioners developed the capability to fence the muskoxen in, allowing the practice to be applied to shallower {{wp|dell (landform)|dells}} and spread into the lowlands, and eventually enabling a limited degree of selective breeding. Originally hunted and herded for their wool, milk, and meat, much later generations of selectively-bred muskox derivatives were (when neutered) marginally suitable for use as draught animals, specifically plough animals, a purpose for which they were employed and continued to be bred in Upper Kirav south of the Ximantav Mountains and as far south as [[Sēora]] and the northwestern Kirish Plain. | |||

After the introduction of true cattle from Levantia, true oxen rapidly replaced muskoxen and muskbullocks as the dominant plough and draught animal. The domesticated muskox derivative remains in very limited use in some traditional communities of Upper Kirav and the Northwest Territories. Muskox herding, on the other hand, is an important economic activity in the far north of the island continent and the [[Coscivian Sea]] islands in the present day. Competition over pastureland has at times been a cause of communal violence between muskox-herding peoples and reindeer-herding peoples. | |||

===Dogs=== | ===Dogs=== | ||

A pygmy dog breed known in Ænglish as the {{wp|Chihuahua|Kirish game hound}} is raised for meat, mainly in the interior and parts of the Baylands. Dogmeat was historically regarded as poor man's fare, but has recently undergone something of a lobster effect and become fashionable among the élite. Consumption of dogmeat was on the decline for much of the modern era, but rapidly expanded during the latter half of the Kirosocialist period due to food scarcity caused by the command economy. As dogs were outside the scope of government planning and not regulated as livestock, they could be raised for sale on the {{wp|black market}} without fear of criminal penalty. Contemporary production is mainly for the domestic market, due to low foreign demand and legal prohibitions in many countries. | A pygmy dog breed known in Ænglish as the {{wp|Chihuahua|Kirish game hound}} is raised for meat, mainly in the interior and parts of the Baylands. Dogmeat was historically regarded as poor man's fare, but has recently undergone something of a lobster effect and become fashionable among the élite. Consumption of dogmeat was on the decline for much of the modern era, but rapidly expanded during the latter half of the Kirosocialist period due to food scarcity caused by the command economy. As dogs were outside the scope of government planning and not regulated as livestock, they could be raised for sale on the {{wp|black market}} without fear of criminal penalty. Contemporary production is mainly for the domestic market, due to low foreign demand and legal prohibitions in many countries. | ||

==Paludiculture== | |||

Great Kirav and [[Faneria]] are the world's leading centres of {{wp|paludiculture}}. {{wp|Peat}} remains an important energy source in Great Kirav and other parts of [[Kiroborea]]. | |||

Traditional paludiculture went into decline during the industrial revolution, as growing demand for energy caused the value of bulk peat and peat fuel briquettes to vastly outstrip that of other peatland products. Intact peatlands were previously used for fishing, hunting, grazing, and gathering, as well as the non-intensive cultivation of sod and other minor products supplemental to the traditional peasant household. Paludiculture is currently being revived in the 212th century with support from provincial peat ministries to promote more sustainable use and conservation of the great Kiravian peatlands. | |||

==Aquaculture== | |||

==Apiculture== | |||

==Economics== | ==Economics== | ||

| Line 146: | Line 172: | ||

*[[Agrarian paramilitarism in Kiravia]] | *[[Agrarian paramilitarism in Kiravia]] | ||

*[[Forestry in Kiravia]] | *[[Forestry in Kiravia]] | ||

*[[Drabbage]] | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 153: | Line 180: | ||

[[Category:2023 Award winning pages]] | [[Category:2023 Award winning pages]] | ||

[[Category:IXWB]] | [[Category:IXWB]] | ||

{{Template:Featured article}} | |||

Latest revision as of 13:48, 26 August 2024

Agriculture in Great Kirav is a major economic activity underpinning local and regional economies across most of the island continent's land area.

As a result of its natural history, the agricultural endowment of the island continent includes both Old World and New World species, and has been supplemented by crops and animals introduced from other continents, such as wheat and cattle.

Even with modern improvements in agronomy, Mainland Kiravian agriculture is insufficiently productive to satisfy enormous domestic demand, and most of the island continent’s food supply is imported, mainly from Levantia, Sarpedon, and South Crona.

Agriculture in Æonara and in other parts of the Kiravian Federacy and Collectivity, such as Sydona, are covered separately.

Crops

Potato

Eat the potato now, or ferment it for later? This is the perpetual dilemma of our People.

— Shafto, Analects of Shafto the Wise

The potato (Coscivian: ēln) is the most important food crop in Great Kirav, and has been since the dawn of agriculture. Potato began to be domesticated as early as 25,000 years ago in the central latitudes of the Western Highlands. The potato plant's remarkable ability to thrive in cool climates and subprime soil conditions made it indispensible to early Kiravian farmers and an enduring staple of the Kiravian diet. Indeed, the potato is credited with enabling sedentarisation of the proto-Coscivian tribes and, indirectly, the rise of Coscivian civilisation proper. Potato is grown throughout Great Kirav, but more so in the north and west. It is the dominant crop in the more marginal lands that make up much of the continent.

Potato planting season typically begins in early spring, depending on the temperature and soil conditions. Observance of the vernal equinox festival Élív includes traditions that celebrate a successful planting effort. Farmers prepare the soil by plowing, harrowing, and levelling it before planting the seed potatoes. The seed potatoes are placed in furrows, and then covered with a layer of soil. Manual cultivators accomplish this with the aid of a mattock. As the plants grow, they are hilled, meaning that more soil is piled around the base of the plant to support it and prevent the tubers from exposure to sunlight. This helps to prevent a green tinge that may affect the flavour and nutritional value of the potatoes. Most parts of Great Kirav regularly experience chilly and wet weather conditions, which can be challenging during the growing season. Frost poses a great danger to the crop in the critical periods just after planting and just before harvest. To protect the potato, farmers may install protective coverings, such as transparent films, over the fields. Harvest usually takes place in the autumn as the leaves start to turn yellow and die back. The potatoes are harvested with machines or by hand, then cleaned, graded, and sorted for distribution. After harvesting, the potato is stored in cool, dry conditions to preserve its quality. The harvest time is celebrated with festivals and fairs, where people can taste different varieties, buy fresh produce, and enjoy other cultural activities.

Potato is used in many dishes such as potato pancakes, potato soup, potato dumplings, and potato casseroles, and can also be milled into potato flour for baking. Beyond human consumption, the potato is also used to produce alcoholic spirits (thasstraśum) and industrial starches, and as fodder for pigs.

Saint Bran is the patron saint of potato farmers.

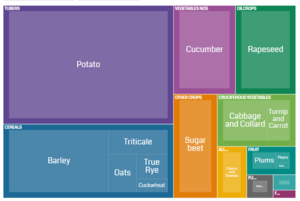

Cereals

|

|

|

The principal grain crops grown in Great Kirav are the Three Reliables: Rye and wildrye, Coscivian cuckwheat, and oats, along with barley, wheat, and triticale.

Coscivian cultures conflate two distinct cereal grasses - Secale cereale or "true rye" and Elymus borealis or "wildrye" - under the label of "rye" (Kiravic: dralm, South Coscivian: drallion). Numerous cultivars of Elymus borealis have been cultivated in different regions and microclimatic zones of Great Kirav for centuries. True rye was most likely introduced from what is now Faneria during the Second Empire. Kiravian farmers were early adopters of triticale, production of which continues to expand in traditionally rye-growing areas. Indeed, it has been proposed numerous times that federal agriculture subsidies be amended to include cash incentives for rye farmers to transition to triticale instead, though such proposals have not yet been adopted.

The best farmland, much of which is concentrated in South Kirav and the warmer latitudes of the Baylands and Farravonia, is dedicated mainly to wheat, barley, and (increasingly) maize, as far as cereals are concerned. Hard red winter wheat is grown in drier mesotemperate areas of the interior, while durum wheat and other varieties are grown mainly in the South. Rye cum wildrye cultivation is well-established the upper supratemperate, hemiboreal, and boreal zones of Great Kirav, on account of the climatic conditions that make it difficult to grow other grains. "Rye" (sensu lato) and oats are resilient crops that tolerate lower temperatures and require shorter growing seasons than other grains, and thus can grow well in the harsh North Kiravian climate, with some especially hardy wildrye cultivars, such as Irovasdra alpine wildrye, being viable on a subsistence scale even at the highest arable altitudes and in the northernmost mesoboreal regions on the Coscivian Sea. Rye is often planted in the fall and harvested the following summer. Kiravian cereal farmers often practice crop rotation, where they alternate rye/wildrye with other crops such as barley, oats, or potatoes. This helps maintain healthy soil and prevents disease vectors and pest populations from building up. As a short-season crop that requires little in the way of fertilisers and pesticides, cuckwheat is often planted between primary rotations. In a few regions, such as southern Kannur, it can be planted as a double crop. Coscivian cuckwheat is also prized as a pollen source to support apiculture.

Vegetables

The sugar beet is a Levantine crop introduced to Kiravia during the 19th century AD. It has naturalised exceedingly well and is cultivated in moderate concentrations, mainly in and around the Lake Belt, but also in parts of Farravonia and certain Western Highland valleys. Sugar beet accounts for about 70% of Kiravian domestic table sugar production, with the remainder from cane, grown mainly in Sarolasta.

[Cruciferous vegetables] [Allium]

Cucumbers

Kiravia is a leading producer of cucumbers, and the cultivation of this notoriously cool vegetable is widespread across various regions in Great Kirav, as well as overseas components of the Federacy and Collectivity. Cucumber cultivation in Great Kirav involves both open-field and greenhouse production. Open-field cultivation is predominant, particularly in the warmer months and climes, while greenhouses are utilised to extend the growing season and ensure a more consistent yield throughout the year, by sheltering the frost-susceptible cucumber plant from the often chilly weather of Kiravian springs and autumns. In addition to greenhouses, farmers in Great Kirav commonly employ other modern agricultural practices, including the use of advanced irrigation systems and high-quality seeds to optimise cucumber production. The cultivation cycle typically begins in spring, with planting and harvesting occurring at specific intervals depending on the cucumber variety and intended use. Both slicing and pickling cucumbers are grown in Kiravia,[1] and together they are the third-largest category of Great Kiravian produce by total annual production value, behind potato and cereals and just slightly ahead of rapeseed.

Allium

Vegetable crops belonging to the genus Allium, such as onion, garlic, scallion, shallot, leek, and chives, are a highly important crop in Kiravian cuisine, and have been so since prehistoric times. These crops are, as appropriate to each species, grown throughout the arable regions of Great Kirav. The most productive Allium-growing regions, however, are Kaviska, the interior plains surrounding the Lake Belt, and Farravonia. Farravonia is also the main garlic, shallot, and chive-growing region. Under the traditional caste-based economy, most onion and leek production in the Kir-majority regions was undertaken by ethnic minorities, namely the Kempans and Kyrnans. Leeks grow exceptionally well in the upper-middle latitudes of the continent on account of their preference for cooler climatic conditions.

The artisanal gathering of wild onions for soup and other cooking is still widely practised in rural Kirav, and as a hobby in suburban areas.

Hops

Hops are mainly grown in areas with an oceanic climate. Major hop-growing regions include the West Coast, South, and parts of the Eastern Highlands and Central Uplands. Kiravian hops supply the Kiravian brewing industry and are also exported.

Pre-mechanisation hop cultivation relied on a large seasonal labour force that migrated annually between hop-producing areas and areas of off-season employment. These workers came to regard themselves as distinct social groups known as the hop clans.

Fruit

Great Kirav has a considerable, if underappreciated, fruit output.

Blessed with enormous swathes of of cool, acidic bog land presenting ideal conditions for their cultivation, Great Kirav is a leading producer and exporter of cranberries, which are grown extensively in the wetlands of Niyaska, Ilánova, Knassania Northeast Kirav, and the Lake Belt provinces.

Feed and Forage

|

|

|

|

A sizeable share of Great Kirav's agricultural output goes toward sustaining its livestock industry. In addition to byproducts of crops harvested for human or industrial consumption, such as oilcake, there are several plant species grown largely or primarily for use as animal fodder and forage. Forage plants often predominate as groundcover on land too marginal to support intensive cultivation of food crops.

Industrial crops

Kiravia is a major producer of rapeseed, which by most measures is its most valuable non-food crop. In supratemperate or hemiboreal regions with oceanic or suboceanic climates, such as the maritime Northwest and certain parts of the Lake Belt, rapeseed is typically grown as a winter crop, sown in late summer or early autumn and harvested in late spring or early summer. However, it can also be cultivated as a spring crop, depending on the region and local weather conditions. The crop is typically sown by direct drilling or broadcasting, and requires regular fertilization and pest control. In supratemperate regions with a continental climate, rapeseed is typically grown as a spring crop, sown in early spring and harvested in late summer. The crop requires similar soil and climate conditions to those in oceanic regions, though farmers in continental climates are more reliant on conventional tillage methods and crop rotation to maintain soil fertility and improve crop yield.

Rapeseed oil has been used by Kiravians since time immemorial as a cooking oil, and was the predominant vegetable oil used in Kiravian cuisine before exposure to imported olive oil and other alternatives. In modern times, the oil is still in very high demand for a wide range of applications, most prominently for the production of biodiesel, as an ingredient in mass-produced margarine, mayonnaise, and other condiments, and for industrial use in paints, lubricants, and soaps. It is Great Kirav's most important agricultural export.

Minor oilcrops grown in Great Kirav include safflower (grown mainly in Îkodha) and sunflower, grown mainly in the South and in Kaviska.

Flax was once grown in large quantities in the South, inland Farravonian valleys, and the northern plains, from Kastera westward to Îkodha and Asperidan. It was valuable as animal fodder and as an oilcrop, but most of all as a textile fibre. A reliable domestic flax supply was once of strategic importance due to its use in weaving sailcloth. Although Great Kirav is still a significant flax producer, the value of this commodity has diminished under pressure from more cost-effective synthetic fibres and oils, and cultivation has contracted accordingly.

Horsetails are abundant in moist environments across the continent, and have been harvested by Kiravians since prehistoric times. Equisetum arvense was used for medicinal purposes and eaten boiled or grilled as a vegetable. In pre-industrial times, Equisetum hyemale was grown in kitchen gardens and its stems used for scouring pots and pans, as well as for sanding and polishing wood. Horsetails are still used for scullery work by many rural households, especially in Third Kirav. Some suburban households have taken to growing horsetails in drainage ditches and catchments in order to access provincial tax benefits.

Other Crops

Other important agricultural products include:

- Allium: Onion, garlic, scallion, shallot, leek, and chives

- Starch crops: Mountain vine, Crisp potato, Kirish moss

- Thanksgiving shit: Pumpkins, gourds, squash

- Deez Nuts: Hazelnut, Shagnut, Chestnut

The northernmost plant farm in Great Kirav (sensu lato) and in the Kiravian Federacy is located in County Kennard on the satellite island of Rhuon. The 60-hectare estate of rocky arctic meadowland grows Rhodiola_rosea for sale to herbal supplement companies. According to its owner, Oxus Ypsōdriv, the farm is "not profitable, but not much work either."

Stock

Stock rearing has always been important to sustaining the Kiravian way of life. Pastoralism is especially important in the numerous area of Great Kirav that are ill-suited to intensive arable farming, such as the upper boreal regions, alpine meadows and tundra, dry leeward mountain slopes, and inner-northwestern temperate grasslands. Kiravians rear animals for meat, milk, hide, horn, and other valuable products, such as insulin. Wool, from camelids and sheep alike, is a top agricultural export.

Many lowland pastoral regions of Great Kirav, such as Venèra and Harma, are characterised by a bocage landscape in which parcels of land are separated by dense (and often very old) hedgerows and wooded berms to facilitate herd management and protect crop fields from grazing livestock. In other regions, such as Vôtaska and Elegia, silvopasture is the norm. Open rangeland grazing is most common in Korlēdan, Îkodha, Enscirya, and the South.

Also sheep.

The tinav is a camelid similar to the llama, guanaco, or alpaca. Its wild-type variant, no longer extant, was native to the alpine grasslands of West Kirav and was domesticated by the time of the Chalcolithic. Stock-raising of the tinav was a transformative event in Kiravian history, enabling the establishment of regular long-range overland trade networks and the geographic extension of political structures such as states and tribute networks. This made possible the Verticalist mode of production under the Emperald Emperors. In addition to its use as a draught animal, the tinav is raised for wool, meat, and...maybe milk?

The tinav has been used as a plough animal in certain marginal (mainly mountainous) lands where larger animals were unavailable or inappropriate. Its use for this purpose was more widespread before the introduction of oxen.

Swine

Suids were likely the first large mammals domesticated by prehistoric Kiravians. The Old Kiravian hog is a domestic variant of the native Nearctic bearded boar, which is likely extinct since the Kiravian Iron Age, though efforts to breed back the Nearctic boar phenotype from Old Kiravian hogs are in progress. Modern swine stocks in Kiravia are generally of mixed ancestry, descending mainly from the Levanto-Sarpic common hog and with a substantial (though gradually declining) share of Nearctic boar heritage. Pure-bred Old Kiravian hogs are raised as a heritage breed, mostly by smaller farms as a specialty product.

For most of recorded Kiravian history, swine were the primary source of meat. Pork and pork products remain the most widely consumed form of meat in the country (fish and fowl excluded), though beef has been steadily gaining ground since the end of Kirosocialism. The swine industry in Great Kirav has been steadily growing since the market reforms of the 1980s AD. Improved access to technology and capital has contributed greatly to this success. For example; Kiravian winters can be harsh, especially in the North and interior, and as such, many swine farmers have developed insulated and climate-controlled facilities to regulate indoor temperatures during extreme weather conditions.The construction of high-capacity climate-controlled swine shelters has greatly improved herd health and meat yields. Improved antibiotics and other inputs have similarly reduced losses and widened profit margins for farmers.

Early urban centres in Kirav employed pigs for sanitation purposes, making use of pig latrines to process human excrement. Pig latrines are fairly rare today, but remain in use by some rural households and remote hamlets in less developed inland states. They are most common in Kyllera, where about a quarter of Coscivian households feed into pig-based waste management systems (PBWMS).

Pig farming is banned in some predominantly Muslim countyships in the Kiravian South.

Cattle

The first attempt to introduce cattle to inland Kirav was made in 25XD4+2Q CC by Oranibur Kaisthev, chancellor to the King of the Antarans. Kaisthev purchased some 400 head of Urcean longhorn cattle to increase the king’s revenues from montane pasturelands. However, upon their delivery to what is now County Upśur in Verakośa, the cattle were immediately slaughtered by terrified locals, who recognised them as the Devil’s hounds. Subsequent attempts were foiled along the same lines.

A strong majority of cattle in Great Kirav are dairy cattle. Dairying is an important activity in the Far Northeast, Upper Kirav (especially Vôtaska, where dairy giant Banya Sēora SAK is based), and upland meadows of the Eastern Highlands and Central Massif. Since 2012 AD, most Kiravian dairy products are sold abroad with the assistance of the Kiravian Dairy Board, and the industry as a whole is now increasingly re-gearing towards an export orientation. Dairy yields have greatly increased in the post-reunification era, while domestic demand remains constrained by the fact that only a minority (~28-36%) of Kiravians are lactose-tolerant.[2]

Beef rearing is a smaller but nonetheless significant subsector of the livestock industry. From the introduction of cattle to the island continent until Kiravian reunification, most Kiravian beef was destined to be corned or otherwise cured. Nationwide distribution of domestic fresh beef did not arise until after the end of Kirosocialism, under which all beef was requisitioned by the government to supply the Kiravian People's Army and supplement the Social Ration. Korlēdan is the leading beef-producing state in Great Kirav. In recent years, beef enterprises in Korlēdan have been consolidating under a local affiliate of the Federation of Daxian Beef Producers.

Other Bovids

Some communities native to the the tundra areas of the North Coast, montane Northwest, and Ximantav Mountains have a tradition of herding muskoxen. It is believed that this practice originated in the northern highlands during the late Neolithic, when hunter-gatherers learned to drive the animals into small, dead-end hollows where herds could be contained and more easily harvested. Over time, practitioners developed the capability to fence the muskoxen in, allowing the practice to be applied to shallower dells and spread into the lowlands, and eventually enabling a limited degree of selective breeding. Originally hunted and herded for their wool, milk, and meat, much later generations of selectively-bred muskox derivatives were (when neutered) marginally suitable for use as draught animals, specifically plough animals, a purpose for which they were employed and continued to be bred in Upper Kirav south of the Ximantav Mountains and as far south as Sēora and the northwestern Kirish Plain.

After the introduction of true cattle from Levantia, true oxen rapidly replaced muskoxen and muskbullocks as the dominant plough and draught animal. The domesticated muskox derivative remains in very limited use in some traditional communities of Upper Kirav and the Northwest Territories. Muskox herding, on the other hand, is an important economic activity in the far north of the island continent and the Coscivian Sea islands in the present day. Competition over pastureland has at times been a cause of communal violence between muskox-herding peoples and reindeer-herding peoples.

Dogs

A pygmy dog breed known in Ænglish as the Kirish game hound is raised for meat, mainly in the interior and parts of the Baylands. Dogmeat was historically regarded as poor man's fare, but has recently undergone something of a lobster effect and become fashionable among the élite. Consumption of dogmeat was on the decline for much of the modern era, but rapidly expanded during the latter half of the Kirosocialist period due to food scarcity caused by the command economy. As dogs were outside the scope of government planning and not regulated as livestock, they could be raised for sale on the black market without fear of criminal penalty. Contemporary production is mainly for the domestic market, due to low foreign demand and legal prohibitions in many countries.

Paludiculture

Great Kirav and Faneria are the world's leading centres of paludiculture. Peat remains an important energy source in Great Kirav and other parts of Kiroborea.

Traditional paludiculture went into decline during the industrial revolution, as growing demand for energy caused the value of bulk peat and peat fuel briquettes to vastly outstrip that of other peatland products. Intact peatlands were previously used for fishing, hunting, grazing, and gathering, as well as the non-intensive cultivation of sod and other minor products supplemental to the traditional peasant household. Paludiculture is currently being revived in the 212th century with support from provincial peat ministries to promote more sustainable use and conservation of the great Kiravian peatlands.

Aquaculture

Apiculture

Economics

Landholding, Enterprise Types, and Labour Relations

In premodern times, labour in the agrarian economy was closely tied to tuva, ethnicity, and caste. Cultivation of staple crops, such as potato and cereals, was generally undertaken by large caste groups who occupied the most fertile and level land, and the descendants of these people form the regional majority Coscivian subgroups recognisible today. In many regions, the cultivation of secondary crops, such as onions and other vegetables, was assigned to minority Coscivian groups.

Policy

Although the share of GDP and employment generated by agriculture has steadily declined since industrialisation, agriculture remains politically important in the Kiravian Federacy. Maintaining a robust agricultural sector in Great Kirav is seen as critical to building a distributed economy and improving regional balance, and for mitigating the island continent's food insecurity as a strategic vulnerability for the Federacy at large. Like many temperate industrialised countries, Kiravia generously subsidises its agricultural sector. Federal subsidies to agriculture in Great Kirav (both the Federation and the South) and Æonara are consolidated under a series of Triennial Agriculture Acts and administered by the Agricultural Executive. The federal subsidy programme covers all of the major food staples and cash crops discussed at length in this article; additional subsidies are extended by provincial governments, and often cover smaller-volume crops, emerging products, and regional specialties with a more limited geographic footprint. In addition to protection of the domestic agricultural sector, the Triennial Agricultural Acts address adjacent policy concerns, such as erosion and runoff mitigation, biosecurity, and the preservation of agricultural heritage. The Agricultural Executive also administers the Agricultural Reform Fund, which disburses payments to large landowners dispossessed by the Kiravian Union.

Markets

Agricultural futures and options are traded on several domestic exchanges. Exchanges whose soft-commodity contracts specify delivery points in Great Kirav are as follows:

- Escarda Grand Exchange - Potato, rye, elymus, cuckwheat, oats, triticale, feed clover, canola, milk, lean hogs, frozen pork bellies, broiler chickens, beet sugar, maple sugar,

- Silverda Mercantile Exchange - Potato, hops, crisp potato, Kirish seamoss starch, mountain vine starch,

- Primóra House of Trade - Barley, hops, wheat, kalir

- Xéulev Hall of Onions - Onions, leeks, cuckwheat, poultry preparations

Exports

Agricultural exports from Great Kirav, whether to the Kiravian colonies or foreign nations, are dwarfed by the massive scale of its imports and consist mainly of nonfood products. Key agricultural exports include hops and other brewing factors, canola and canola oil, dairy products, wool, kalir, flax fibre, potato-derived industrial starches, treenuts and treenut oils, and soaking herbs.

Since the return of capitalism, there have been efforts by the government and agricultural coöperatives such as the Kiravian Dairy Board to promote agricultural exports to foreign markets.

See Also

Notes

- ↑ Slicing cucumbers are often cultivated for fresh consumption, while pickling cucumbers are processed for the production of pickles.

- ↑ Lactose tolerance is highest among the Celtic-Kiravian and Levantine-Kiravian minorities; among Coscivians it is highest in Ĥeiran populations and is indicative of historical Levantine (mainly Celtic) admixture.