Prehistory of Great Kirav

According to all known laws of anthropology, there is no way that Great Kirav should ever have been settled. The odds of modern man a) reaching and b) surviving in Great Kirav during the time periods currently deemed reasonable by the scholarly community, much less prospering there to the degree now believed, are beyond astronomical and require a suspension of disbelief too great for most Occidental scientists to even approach the topic. Kiravia, of course, exists anyway, because Kiravians don't care what Menquoi think is impossible.

— B. Kinoflixin, Towards Ethnohistory - An Interdisciplinary Approach to Boreal Prehistory

The distant past of Great Kirav is steeped in mythology and remains obscure. Archæological evidence suggest that the region may have been inhabited by modern man as early as 22,000 years ago, and subsequently beset with multiple waves of migration that have left enduring genetic, archæological, and cultural imprints on the island continent. The bulk of the genetic heritage of Kiravian peoples is attributable to an Ice Age migration from Levantia made possible by lower sea levels and dense floes of pack ice, with later contributions from the Ʒ-Q transoceanic migration and the still-unaccounted for progenitors of Haplogroup Ȼ.

Unravelling the truth of Kiravian prehistory and dark history is complicated by Coscivian culture's schizo-sacramentalist conception of reality (which does not clearly distinguish between what Occidental cultures would regard as the symbolic and the real) and its unique approach to time (which is often reflected in non-linear narratives and the confounding expression of temporal processes in spatial or virtual terms). This article will present the best current scientific understandings of Kiravian prehistory, contextualised by Kiravian traditional narratives and the research of dark philologists.

Pre-Human Times

Palaeozoic Era

Much of Great Kirav's plant biodiversity dates from clades attested from the Carboniferous through Permian periods.

Mesozoic Era

The Mesozoic Era of Great Kiravia, defined as an era as encompassing the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous Periods on the continent of Great Kiravia, lasted from about 252 to 66 million years ago.[1] Often referred to as the "Age of Reptiles",[2] it is characterized by the dominance of archosaurian reptiles such as the dinosaurs, an abundance of gymnosperms (such as ginkgoales, bennettitales) and ferns, a hot greenhouse climate and the tectonic break-up of Pangaea. The period is defined geologically as beginning with the first appearance of the Conodont Hindeodus parvus and ending with an Iridium enriched layer associated with a major meteorite impact in modern-day Daxia and subsequent K-Pg extinction event. It is also sometimes referred to as the "Age of Conifers" in Great Kiravia due to the abundance of fossilized material from coniferous trees.[3]

Great Kiravia is unique in the Mesozoic for being an island continent with only very little outside contact following the Pangaea-Kiravia split at the end of the Triassic period.[4] With basal clades of pterosauromorphs, theropods, sauropodomorphs and ornithischians already inhabiting Great Kiravia at the time of the split however, these were able to evolve and diversify independently of archosauromorphs elsewhere, resulting in numerous examples of convergent evolution with otherwise very distantly related genera but also many examples of island gigantism, island dwarfism and notably of Bergmann's rule.[5] Evolution on the continent of Great Kiravia was heavily influenced by its three distinct biomes; a volcanic nearly arctic climate in the far north, a temperate highly arboreal climate in the south and a major riparian border zone in-between the two characterized by rolling plains and river deltas.[6]

Despite a relatively limited number of clades of synapsids, dinosauromorphs and pterosauromorphs occupying Great Kiravia following the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event, the paleobiological diversity of Great Kiravia appears to be only slightly weaker than that of Sarpolevantia in the advent of the Cretaceous, suggesting a rapid and diverse evolutionary process had taken place during the Jurassic to fill all the niches left open by the T-J event.[7] At least one clade of small Kiravian theropods appear to have evolved powered flight independently of their Sarpolevantine counterparts during the late Jurassic period; there is also physical paleontological evidence of feathers in many theropods of various sizes in Great Kiravia, lending further evidence to the theory that feathers are ancestral to archosaurian reptiles.[8] Like the rest of the world, the Cretaceous period ended when the K-Pg extinction event occured following a major meteor striking central Daxia, causing the mass extinction of all non-avian dinosaurs and most other tetrapods weighing more than 25 kilograms (55 pounds).

Cenozoic Era

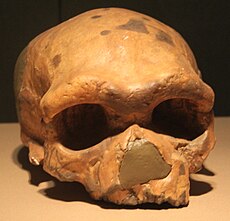

Earliest Homonids

During the late 20th century AD, palæontologists unearthed skeletal remains of archæic humans present in Great Kirav during the middle Pleistocene, which were eventually concluded to represent two distinct species. The more anatomically archæic of the two, Homo vetus montanus, appear to have been sluggish, shuffling creatures; dull but hardy tundra-dwellers with a robust physique and limited cognitive and linguistic capabilities compared to the more anatomically "modern" H. darudensis. Although direct evidence is lacking, most palæontologists find it probable that both species were more hirsute than modern man, with ample body hair aiding their survival in the glaciated conditions of Pleistocene Kirav.

|

|

Deep Prehistory

First Humans - Ice Bridges from Demomap

The present accepted consensus regarding the colonisation of Great Kirav by Homo sapiens sapiens maintains that the island continent was first peopled by a founder population of marine mammal hunters originating from the north-central Levantine mainland who migrated across pack ice in pursuit of prey until eventually reaching pockets of unglaciated land (now likely submerged) along the ancient southern and southwestern shores of Great Kirav. This theory is colloquially known as the "iceberg-hopping thesis" (Coscivian: xistoīoribakursa). This migration is believed to have occurred sometime between 19,500 BC and 18,500 BC, though the lower bound of this window is not definite and the upper bound could be as late as the first abrupt rise in global sea levels around 18,000-17,500 BC.

Dark historians generally identify the homeland of the Ice Age Levantine migrants with the mythological concept of Demomap. Although variously interpretable from the oral traditions of Coscivian and Urom communities as a place, time, or abstract state of being, Kapuśitic and Cuomo-Passaic-speaking peoples present Demomap as the intermediate location of their ancestors between their emergence from the Shadow Realm and their arrival in Kam, interpretable either as the physical world at large or Great Kirav specifically.[9] As such, the hypothesised pre-migration prehistory of the proto-Kiravians is known as the 'Demomappic Period'. The proto-Kiravians of the Demomappic Period are associated with a particular lithic technique (examples of which are portrayed here) with examples known from both Ilánova and finds in Kubagne, Yonderre and [LOCATION], Caergwynn, cited as the strongest archæological evidence of the iceberg-hopping hypothesis. During the Demomappic Period, the proto-Kiravians are currently believed to have interacted economically and reproductively with the Packer Culture of the Vandarch Basin but remained culturally distinct therefrom.

Primitive Period - Cold and also Dark

The era of human habitation of Great Kirav from initial migration to the the commencement of the last glacial retreat around the middle of the 12th millennium BC, a range of roughly seven thousand years, is known as the Primitive Period, and is largely synonymous with the Kiravian Palæolithic. The human population of Great Kirav during this era is presumed to have been extremely sparse. Some studies from the 1980s-90s AD suggested that the Archæo-Cronan and Archæo-Levantine founder populations may have numbered as few as 70 and 100 people respectively. More recent works accept figures higher up in the hundreds or even low thousands as plausible, with the caveat that the vast majority of migrants' genetic lineages became extinct during the Primitive Period and are not ancestral to modern Kiravians. Whatever its size, almost the entirety of this population would have lived on lands that are now submerged, severely limiting what can be gleaned about this earliest phase of Kiravian prehistory from archæological remains. As such, almost nothing is known about this period from modern science, and almost all that is comes from a handful of excavations in Ilánova and South Kirav.

Environmental conditions during the Primitive Period are believed to have been exceedingly harsh. The island continent was almost entirely glaciated during this time, and prehistoric Kiravian populations would have clung to its habitable coastal fringes, eking out a marginal living from hunting, gathering, and fishing.

Convoīon Culture

The next archæological culture to develop out of the Demomappic, appearing by 17,600 BC, was the Convoīon Culture, known from a handful of sites in Ilánova. Convoīon exhibits a much more diversified toolmaking repertoire, utilising a wider range of materials than the stone-prone Demomappic to include hematite, worked animal bones, and other naturally-occuring substances. The dramatically more sophisticated tool inventories found at so few dig sites suggests a society much more advanced in its economy and comfortable in its surroundings than its Demomappic predecessors, migrating less frequently and availing themselves of more thitherto untapped food sources. The Convoīon Culture appears to have employed more specialized hunting, fishing, and collecting techniques, in contrast to the post-migration Demomappic generalist hunters. It is also the Convoīon culture that left the first unambiguous examples of rock art in Kiravia.

Society I (ca. 12,500 BC - ca. 9600 BC) - We Live in This

Come the Late Ice Age, glacial retreat and gradual warming of the climate allowed Kiravians to break out from their highly constrained High Ice Age mode of production, enabling population growth and the formation of societies beyond the scale of primitive bands.

This is a time of dramatic (but mostly good) change for Kiravians, whose material culture advanced considerably into what is known as the Lower Kiravian Epipalæolithic or the Society I Culture in response to major environmental shifts, beginning with a second abrupt rise in sea levels around 12,475 BC. This rise in sea levels effected the submersal of what were presumably the most heavily populated coastal areas of Kirav, but the glacial retreat responsible for it also opened up more inland areas to ecological colonisation and subsequent human habitation.

During the Late Ice Age, the continental ice sheet that had previously covered most of the continent contracted to the island continent's central basin, flanked by the Aterandic, Ximantav, and West Highlands ranges.

The people of the Society I culture formed somewhat larger social groups than their predecessors, and many communities lived as (at least seasonally-)sedentary food collectors, using markedly more sophisticated social organisation and lithic tools to extract sustenance from a wide variety of sources. Evidence of semi-permanent settlements and specialised tools disappears around the time of the Pleistocene-Holocene transition, suggesting that the Society I culture collapsed under pressure from major environmental changes, reverting to a smaller-scale hunter-gatherer lifestyle for several centuries.

[The Glacier and its lasting psychic effects]

Pleistocene-Holocene Collapse

The Kiravian Epipalæolithic or Gameritic Upheaval was a time of dramatic (and mostly bad) change for Kiravians.

Natural cataclysms and their secondary environmental effects, namely disease and the disruption of essential food sources, caused the collapse of Society I and the abandonment of its characteristic permanent settlements. Most dark historians are of the opinion that the psychological and cultural impact of the Pleistocene-Holocene transition was incredibly traumatic, leaving a lasting impact on the Kiravian worldview.

Society II (ca. 9300 BC - ca. 8000 BC)

A second period of technological progress began during the late 9th millennium BC, giving rise to the Society II culture, another pre-agricultural culture of sedentary food collectors. Society II communities were larger and more permanently settled than those of Society I, exhibiter better adaptations for survival in more inland areas, and may have practised primitive forms of horticulture at later stages. Society II appears to have collapsed abruptly around 8300 BC, for reasons still unknown. The period during which Society II emerged is known as the First Kiravian Mesolithic.

Some dark historians believe that the first incarnation of the Coscivian Empire, a tribal confederation referred to in modern texts as the Lawful Commonwealth, arose during the latter half of Society II. Others believe it arose during Society I, whereas Occidental scholars and Coscivians of a more scientific bent hold that the Lawful Commonwealth (if historical at all) could not have formed before the Neolithic consolidation of simple farming societies.

Using their arcane ability to divine fully-fledged visions of lost civilisations from examination of pottery shards, archæologists have theorised that Society II settlements exhibited a remarkably high degree of social stratification for a pre-agricultural society, perhaps even practising slavery.

Akai Collapse (ca. 8000 BC)

See also: Kiravo-Akhai Origins Conspiracy Theory

The Akai Collapse, by convention, marks the beginning of the end of Deep Prehistory and the beginning of the beginning of Near Prehistory. This distinction is mainly of significance to dark philologists who place certain foundational events in Coscivian history, such as the formation of the Lawful Commonwealth at a much greater time depth than Occidental archæology permits, toward contemporaneity with Society I and/or Society II. For archæologists, it marks the boundary between two superiodisations of the Kiravian Mesolithic: the comparatively rapid growth and development period of Society II prior to the Akai Collapse, and the slower, more gradual period of material redevelopment thereafter, which is dubbed the Second Kiravian Mesolithic and lasts until the inception of true agriculture.

Near Prehistory (ca. 8000 BC - 3200 BC)

Archæic Era (8000 BC - 5700 BC)

The Archæic Era is demarcated from the conclusion of the Akai Collapse to the beginning of the Formative Era ca. 5700 BC, spanning the cusp of the upper Mesolithic and lower Neolithic. It is characterised by the gradual adoption and proliferation of agriculture and pastoralism among the simple tribal groups that would remain the most consequential socio-political entities on the continent for millennia to come. Tribes in the most advanced regions of the island continent would develop robust agrarian economies and corresponding cultural systems during this time, while those in the most laggard regions progressed only modestly beyond the Mesolithic baseline.

Advent of Agriculture

As the massive ice sheets that had covered the interior and northern coast of the island continent diminished and finally disappeared, prehistoric Kiravian tribes fanned out across the full breadth of Great Kiravia and gradually began to embrace sedentism a third time. This time, however, the exit from hunting and gathering would be made permanent by the discovery of agriculture. It is currently believed that the domestication of plants was first achieved in South Kirav between 7700 and 7500 BC, where wild Echinochloa kiraviana was domesticated into a cereal crop now known as Kiravian millet (at best a cousin of true millet) and presently cultivated as a fodder crop. Due to its short growing season, drought-resistance, and general hardiness, Kiravian millet proved suitable for cultivation beyond the mild plains of South Kirav, and were found to be viable in a wide variety of environments further north and higher upland. The spread of primitive agricultural techniques across the southerly latitudes spurred several subsequent episodes of domestication, next in the form of the nutritious and delicious potato and crisp potato. The starchy tuber was first cultivated on the lower slopes of the south-western highlands between 7000 and 6000 BC. A separate farming culture centred on buckwheat cultivation and beekeeping emerged on the eastern coastal plain toward the end of that timespan. It is not yet definitively known when or where Elymus grasses began to be grown by Neolithic Kiravians, but cultivation was well underway in the Elegian Valley by 6900 BC.

The Nearctic bearded boar was the first mammal to be domesticated in Kiravia,[10] giving rise to the Old Kiravian hog that is partially ancestral to modern swine stocks in Kirav. While some sort of commensal relationship between man and boar may have existed among sedentary food-collector communities during Society II, with swine feeding off tidally deposited shellfish and algæ supplemented by human food waste from middens, true domestication occurred in multiple locations shortly after sedentary agriculture took root. Domestication of camelids, yielding the tinav, would take place in the Western Highlands much later, during the third millennium BC.

Archæic Society

At the dawn of agriculture, certain patterns of social organisation had already settled into prevailing norms across the island continent. Tribes, in the strict sense of the word, had replaced lower-level band societies in all but the most marginal and inhospitable locales. Kiravian tribes were structured according to segmentary lineages, most of which were already strictly patrilineal and patrilocal as all Coscivian peoples are today, though a minority (now conserved only in a few urom tribes) were matrilineal and/or matrilocal. At this stage it is presumed that all or most tribes permitted cross-cousin marriage, though the extent to which it may have been preferred (as in later stages of both Coscivian and urom societies) is not yet known. Due to the segmentary lineage reckoning of kinship, the demographic size of a typical Kiravian tribe during the early agricultural age is somewhat imprecise, but it can be estimated that during the Mature Archæic period the largest tribal orders of stable political (that is, military) significance claimed common descent no further back than five generations (to a single great-great-great-great-grandfather) and probably included between 1,000 and 3,000 people. However, the everyday lives of early agrarian Kiravians would have been lived largely within the confines of autonomous village communities within a larger tribe, with such villages comprising between 50 and 400 people. By this point, prehistoric Kiravians were actively cultivating potato and crisp-potato, and keeping swine, yet there is little evidence of major forest clearance for agriculture. Pollen analysis suggests mostly small-scale clearance to enlarge natural clearings in the primæval Kiravian forests. The short-term nature of the settlements suggested by a paucity of archæological remains of permanent structures comports with the lack of evidence for large-scale clearance, suggesting that during this period of Kiravian prehistory there were no communities large enough to require a large area of cleared cropland to satisfy their subsistence needs. It has been argued that the overall lack of houses points to a quite mobile society dominated by shifting cultivation. Later, Prehistoric Kiravians developed of slash-and-burn agriculture, using fire in controlled burns to fertilise the mediocre soil covering most of the continent with the rich nutrients accumulated in its thick forest cover. As such, villages would periodically migrate within a localised ambit in search of virgin land as the cinder-enriched soils of one area were depleted. Some anthropologists (mostly - though not entirely - in the Coscivian world) theorise that stress on the land and the contraction of these ambits due to growing populations and the generational fission of villages may have considerably increased the frequency of inter-tribal violence, which could be the historical basis for the Age of Blood described in Coscivian mythology.

Early agricultural Kiravians became embroiled in a state of endemic warfare, not unlike that which has been documented among other relatively high-density simple farming societies elsewhere. Oral literary sources speak little about the causes of this phenomenon, but comparative studies of tribal societies with high rates of endemic warfare at similar stages of development and with economies similar in scale and mode of production to those which have been reconstructed for early agricultural Kiravia (albeit located primarily in the tropics) suggest that swine raids and swine theft were major drivers of conflict, was well as the abduction of women and the imperative to exact revenge for such transgressions. Ecological anthropologists theorise that stress on the land from intensive slash-and-burn cultivation and the contraction of tribal ambits due to growing populations and the generational fission of villages was a key driver of conflict.

— C.V. Telthaskiven, Condensed Scientific Defences of the Historicity of the Great Law Chant

Ʒ-Q Invasion

The Y-DNA haplogroups Ʒ and Q appear in the Kiravian gene pool around 7000 BC. Modern frequency distribution of these haplogroups correlates with two main variables: Proximity of subjects' ancestral home to the West Coast, and belonging to a traditionally Itaho-Atrassic-speaking ethnic group (such as Qihuxians, Ūtrans, West Coast Marine Coscivians). As such, the Ʒ-Q influx is most commonly attributed to a trans-oceanic migration from Crona or alternatively Vallos-Polynesia (a minority theory) as part of the wide-reaching dispersal of chiefly Audonian-origin peoples through the aforementioned regions beginning circa 8000 BC. Archæological and dark philological evidence points to this migration accelerating into a violent invasion of Kiravia by more advanced wandering Audonians that spread up and down the West Coast and inland therefrom until running up against early adoptors of potato-based agriculture, who were a closer match to the invaders militarily and enjoyed the advantage of highland geography in defending their homes.

Along with the Itaho-Atrassic language family, which is now generally accepted to descend from the language of the Ʒ-Q founder population, the most consequential known feature of these migrants' legacy is the introduction of the oceangoing canoe technology to Great Kirav.

Formative Era (5700 BC - 3200 BC)

The Formative Era encompasses the proto-historical phase from 5700 BC to the appearance of the oldest reliably dated narrative epigraphs around 3200 BC that mark the beginning of the Preclassic Era. Together with the Lower Preclassic, it constitutes the age studied as 'Deep History' (biþniaxira) in Kiravian academia. The Formative Era witnessed the rise of more complex agricultural societies with the requisite resources, labour specialisation, organisation, and cultural-religious sophistication to undertake large-scale construction of structures and monuments for the first time since Society II, leaving an impressive archæological footprint. All of the true civilisations that would feature in preclassical and classical history, including the Coscivian, have their roots in this period, which is why it is so named.

Mainland Antemegalithic

The early to middle fifth millennium BC saw the formation of more permanent settlements and larger-scale (though still thoroughly tribal) social organisation. Permanent settlements featuring stone structures reappeared in appreciable numbers for the first time since Society II. The causes of this mostly contemporaneous increase social and technical complexity across disparate regions of the island continent remain an active area of research, and a variety of theories proposing climatic, ecological, economic, and social-cultural factors enjoy some degree of acceptance among scholars. Traditional Coscivian historiography relates this process to the end of the Age of Blood described in Coscivian mythology[11], though scholars of a more scientific bent are reluctant to accept such a theory without a solid backing of material evidence. A significant camp rejects the premise of a sudden 'emergence' or 'break' from the Archæic to the Formative entirely, attributing the transition to the cumulative and compounding effects of millennia of incremental advancements.

The region of South Kirav, cradle of the millet-growing, hog-rearing Voskresen culture, had seen the rise of multi-crop agriculture as new crops and farming techniques diffused down into the region: Potato cultivation expanded southward down the Farravonian Central Valley via the Madar River, Elymus had spread down the Issyr, and honey-buckwheat agriculture had expanded southward across the eastern coastal plain. As crops grew more diverse and moved downstream, High Neolithic Southern farmers increasingly needed to collaborate at a greater scale in order to manage their increasingly complex agriculture. This need for higher-order collaboration to facilitate water management and seasonal crop rotation predictably invited the consolidation of larger settlements and more complex modes of social organisation resting on a more elabourate social contract than had previously existed among simpler farming societies. This multi-crop agriculture extended the growing season, bolstered yields, and reduced the frequency and devastation of crop failures, eventually resulting in surpluses and a takeoff in population growth.

Tribes in the more southerly latitudes and middle altitudes of the Western Highlands that relied on the potato as their staple crop experienced lower rates of endemic warfare during the Archæic Era than comparably intensively-agrarian lowland tribes, likely thanks to geographic barriers that encouraged the formation of stable communities in protected valleys. Variance of microclimatic and other agriculturally-relevant environmental conditions across different parts of the mountainous landscape encouraged intercommunity barter and allowed for the peaceful diffusion of pottery industries and lithic techniques across relatively long distances, forming an identifiable and cohesive material culture known as the Mount Alvarin Culture.

The oldest unambiguous examples of proto-writing in Kiravia, in the form of Moon runes, date to ca. 5500 BC and were unearthed in western Trinatria in 2007 AD. It is disputed whether Moon runes represent an instance of the independent invention of writing or the concept of abstract symbolic inscription was transmitted from the Levantine Fenni to Great Kirav via Éorsa.

Éorsan Antemegalithic and Coscivian Origins

The same conditions that had prevailed on the Kiravian mainland during the Archæic Era (constant endemic warfare between small, tribal groups practising shifting cultivation) were also the case on the offshore island known classically as Éorsa and now more commonly called by its Gaelic-derived name, Ilánova. However, sometime around 6000 BC, significant changes took place on Ilánova that allowed its inhabitants to break the cycle of endemic violence that plagued the mainland and advance to a higher stage of social and technological capability earlier than any mainland region.

Deep historians of the realist school relate the advances of the Éorsan Antemegalithic to politico-cultural changes described in Coscivian mythology, namely the rise of the Emperors, who imposed the Four Laws and Four Rites and forged a tribal confederacy capable of overwhelming any individual hostile tribe and - crucially - also capable of maintaining peace and cohesion within itself. Most such writers do not make a case for the historicity of Emperor Ĥ or his Pentorchid Dynasty, but rather argue that narratives about these legendary Emperors and their edicts served as a charter myth legitimising an actual, historic system of paramount chieftaincy and customary law that had developed organically among a subset of Éorsan tribes and would eventually hold sway over most of the island. According to them, the primitive form of collective security provided by this Lawful Commonwealth (as both the mythical and historic confederal structure are known) operated in a simple threat environment wherein numerical superiority was sufficient to guarantee victory. Lawful tribes (parties to the Commonwealth) were thus safer from attack than Lawless tribes because they could rely upon neighbouring Lawful tribes for defencive assistance or retaliation. This allowed for increased population growth among the Lawful tribes by sparing them from the extremely high death rates from warfare that afflicted the Lawless tribes, providing additional fighting-age men that galvanised the overall deterrent effect. Larger populations could muster numerically superior fighting forces, which allowed the Lawful tribes to expand territorially into larger (though still thoroughly tribal) political-territorial units, and enhanced the military strength of the Lawful Commonwealth as a whole. This school of throught credits the peace and stability brought about by the hegemony of the Lawful Commonwealth with enabling the advancements of the High Neolithic to take place earlier on Éorsa than on the mainland, including the erection of the first stone buildings since the collapse of Society II, the construction of permanent and extensive settlements and ritual complexes, the intensive cultivation of polycultures with crop rotation, and the undertaking of risky and logistically challenging ventures such as ocean voyages.

Éorsan Migrations

The maritime technology introduced to Kiravia by the Ʒ-Q Invasion (or Itaho-Atrassic invasion) spread fairly rapidly around and up the coasts of Great Kirav, with their adoption by littoral peoples continuing along the eastern seaboard and from there on to Éorsa. As there is no unmistakable evidence of successful outbound canoe voyages from any part of Kirav prior to those launched from Éorsa (hypothetical visits to Eusa nonwithstanding), it would appear that intangible assets associated with the Ʒ-Q founder population's oceangoing canoes, such as navigational techniques and understanding of currents, was not transmitted as readily as knowledge about constructing the canoes themselves, and may even have died out among Ʒ-Q descendant communities after their settlement in Kirav. In Éorsa, oceangoing canoes enabled large-scale (by the standards of the era), multi-directional outward migration - or more accurately, back-migration - from Éorsa in several waves. Some Éorsan seafarers rowed back toward the Kiravian mainland from whence the original settlers of the Éorsan had come many thousands of years before and made landfall at multiple points along the Great Kiravian seaboard, and a few rowed northward to Koskenkorva, where the remainder of their ancestors are now known to have originated. Others, however, set courses for (or simply had the good fortune to arrive in) northern Levantia (directed mainly toward what is now western Faneria, Covina, Suderavia, and {controversially} Wintergen), amounting to a resumption of contact between Kiravians and the lands from whence the pioneering Demomappic Ice Age settlers of Kirav had departed, quite likely for the first time since 18,500 BC.

Survivorship bias of archæological and non-archæological evidence leaves the failure rates of Éorsan canoe expeditions uncertain, but at some point proto-Coscivian mariners must have attained sufficient mastery of their craft to make permanent overseas settlements viable and maintain semi-regular intercourse between these colonies and the home island. Those who made the crossing were speakers of the Koskan phylum of the Cosco-Adratic languages, and the several modern branches of the Koskan languages (i.e. Mainlandic, Kasavic, Eridanic, Tholian, and Austro-Kiravian) are held to each correspond to a specific cluster of Éorsan settlement established sometime during the Formative Era. Such settlement clusters also correlate with the earliest centres of megalithic construction on the mainland (see below).

Back-migration is estimated to have begun around 6750 BC and continued to trickle on thereafter, transferring important agricultural breakthroughs such as and buckwheat cultivation to the mainland, as well as advanced apicultural techniques adapted to Boreal bee species. It is evident that some, if not all, of the waves of back-migration from Éorsa must post-date the consolidation of the historical Lawful Commonwealth, because the emigrants carried the Four Laws and Four Precepts and the rudiments of the proto-ethnic Coscivian identity with them. In the Levantian colonies, this marks the beginning of the history of the Mainland Coscivians. With the arrival of the technologically sophisticated Fenni in the Vandarch 6000-5000 BC, semi-regular trading voyages between Great Kirav and the Mainland would eventually take place, and indeed would later accelerate as the Fenni became well-established in the region and the economies of mainland Kiravian societies (proto-Coscivian and otherwise) became more sophisticated.

Megalithic Societies

Sedentarism and proto-urbanisation allowed for burial practices and the understanding and practice of religion to become more developed. Earlier Kiravian burials were often marked with small stone cairns, but more permanent and sophisticated burial monuments than this would appear only in the latter half of the Kiravian neolithic in the form of standing stones and steles - some of these steles show traces of moon runes and other examples of proto-writing. Monumental works would truly come into their own with the emergence of the cross-Kilikas megalithic culture, during which time more sophisticated societies - hypothesised to chiefly be chiefdoms in terms of political development rather than mere tribes or true states - were able to organise the labour- and time-intensive construction of massive stone monuments in service to their increasingly complex economic and religious needs. These centres of megalithic construction appeared in relatively qucik succession in the Baylands and adjacent portions of the South, and pockets further up the eastern and western seaboards, from which their approach to social organisation and construction would spread over successive centuries, leaving behind a widely distributed body of menhirs, dolmens, stone circles, kistvaens passage graves, tumuli, and statues, as well as the remains of settlements.

Megalithic farming societies continued to depend upon potato and other root vegetables, Kiravian millet, buckwheat, Elymus, honey, and swine (Nearctic boar) for the agricultural foundation of their diets, engaging also in extensive fishing, hunting, and foraging activities.

Vertical Empire

By far the most advanced civilisation to arise during the Upper Formative was the Vertical Empire. Successors to the Mount Alvarin Culture of the Lower Formative, the Vertical Empire in its 'classical' form extended across most of the southern extent of the Western Highlands and possibly parts of the Coast Ranges. It was a centralised monarchical state - most anthropologists believe that the Vertical Emperor was worshipped as a living deity or similarly exalted figure - with a sophisticated administrative bureaucracy overseeing its unique command economy.

Despite being far outstripping its contemporaries in terms of size, population, wealth, and political capacity, the Vertical Empire did not survive beyond the Formative Era, instead rapidly collapsing around 4000 BC.

Megalithic Coscivians

The diffusion of megalithic technology took place chiefly in a coastwise manner, flowing outward from Éorsa with seaborne emigrants and establishing itself first in coastal beachheads before gradually extending into the hinterland, presumably through a mix of settler expansion and the adoption of megalithic techniques from the Éorsan settlers by neighbouring peoples. Present academic orthodoxy in Kiravia maintains that the emergence of megalithic building on Éorsa and its spread to the Éorsan diaspora overseas was made possible by the much greater social stability enjoyed by the Lawful tribes of the island, but made imperative by their particular religious system of Emperor-ancestor worship and Lunar Monotheism, which demanded monumental funerary structures and celestial timekeeping complexes-cum-temples in service to the Ancestors, the Ascended Emperor, and the Divine Moon.

The figure of the Emperor remained important in prehistoric Kiravian cultures, diffusing beyond the tribal and geographic bounds of the former Commonwealth. During the more mature Megalithic, the early Coscivians built giant stone sculptures representing the eternal Emperor as a religious figure from whom chieftains derived legitimacy and to whom they appealed for favour. The mythologies of most Coscivian groups today feature descent from one or more of the original Emperors, and it is believed that such myths date back to this period in the past when Emperor-worship became combined with preëxisting traditions of ancestor worship. Through this synthesis and the consummate sacralisation of the Emperor, the Four Laws and Four Precepts were cemented as religious laws and precepts (if they had not already been such for centuries), and a proper Coscivian macro-ethnic identity took shape as the legacy and laws of the Lawful Commonwealth became the patrimony of the Ancestors, embodied in the Emperor as the greatest among the Ancestors.

Importantly, the infusion of Itaho-Atrassic marine technology would facilitate back-migration from Éorsa to the Kiravian Mainland. It has been demonstrated that back-migrations from Éorsa sometime between 4500 BC and 3500 BC (though possibly earlier) were responsible for the spread of the Austro-Kiravian (Kuomo-Passaic + Kapushitic) languages to southern and western coastal Kirav on one hand and the spread of the Transkiravian languages to northeastern Kirav, Koskenkorva, and far northwestern Levantia on the other (see map). Indeed, back-migration to Levantia also continued during this process, carrying this nascent Coscivian identity to the existing Kiravian-descended communities of continental Levantia. There is every reason to believe that a common culture extended across the Macro-Koskenkorvan-speaking, megalith-builder cultures along this bicontinental maritime transmission belt.

Old Adratic civilisation

A separate megalithic society, the Adratic, emerged in the inland Texta Valley around the same time as the proto-Coscivian megalith builders, though it would appear that the Adrates began megalithic construction independently of any contact with the coastal megalithic cultural centres. The old Adratic tongue and its Classical Adratic and Modern Adratic descendants (the latter of which is still spoken by small populations today) are currently classified under the Para-Koskan phylum of the Cosco-Adratic language stock. There is an abundance of archæological evidence demonstrating that the Old Adrates were proto-Sarostivist devotees of the Divine Moon, like many other Kiravian peoples of this time, including the Megalithic Coscivians. Unlike the Coscivians, however, the Adrates did not observe the Rites and Precepts and had not restructured their ancestor worship around the Emperor. It is known from later Classical Adratic writings that the Adrates believed that they were creations of the Divine Moon and had previously lived on the Moon, and descended directly from the Moon to Kam (either Earth or specifically Great Kirav).

Other early civilisations

Other, more isolated, pockets of relative civilisation would appear on the Mainland while Megalithic Coscivian civilisation made its inroads from the coasts and Adratic civilisation arose in the Texta Valley. The ancestors of the Demarești, for example, developed a parallel civilisation during this time, having independently emerged from the Age of Blood and apprised themselves of the social and technological advances necessary to produce large structures.

- Proto-Demarest - Demarest did not construct megalithic edifices, preferring instead to employ rammed earth in their construction efforts, but did achieve a comparable level of social complexity and stratification to the Megalithic Coscivians and the Adrates.

- Caoi - The isolated Caoi people of the Gypsum Plains had permanent stone settlements during the Coastwise Megalithic, remains of which are accessible for study outside of Restriction Zone 48, where the surviving modern Caoi colonies are located.

Transition to Ancient History

The transition to from prehistory to ancient history is marked by the emergence of the First Dynasties and their consolidation of the first true states, and culminates with the conquest of the Adratic civilisation by Emperor Xoagus I, beginning the First Empire. Methodological and academic justifications for this convention include the nature of predynastic proto-writing and writing: Although writing was known to the Coscivian and Celtic druids during the Megalithic, its use was ritual and monumental, and no long-form written texts suitable for use as historical rather than archæological source material have yet been recovered from this era.

Footnotes

- ↑ All times given by the Gregorian calendar unless otherwise stated.

- ↑ A term coined by Bergendii polymath Gideon-Raphael Mantelleaux in 1843.

- ↑ Balboa, Maximus: A comprehensive history of paleontology, pg. 3. 2004.

- ↑ The exception being marine reptiles and intercontinental ocean-going pterosaurs like Quetzalcoatlus.

- ↑ Bergmann's rule, named for Yonderian paleontologist Hieronymous Bergmann, states that populations and species of larger size are found in colder environments, while populations and species of smaller size are found in warmer regions.

- ↑ Konsaháken, Vurdhan: Paleogeology of Great Kiravia, University of Belarus, pg. 14-19. 2012.

- ↑ Lyukquar, Ansar: Kiravia and the Mesozoic, pg. 67-69. 2015.

- ↑ Balboa, Maximus: A comprehensive history of paleontology, pg. 104. 2004.

- ↑ In the narratives of Transkiravian-speaking peoples such as the Kir, Demomap is equated to Ixnaī, though the mythological significance of Ixnaī is somewhat different.

- ↑ Genetic evidence shows that canids accompanied the Ice Age pioneers over the ice and land bridges from Levantia.

- ↑ Orthodox deep history understands the transition from the Archæic Era to the Formative Era as part of the this to the diffusion of norms that had proven advantageous to the Lawful Commonwealth outward beyond its direct sphere of influence, even continuing after its demise, as the Great Law Chant states [link to section], enabling the formation of other higher-order tribal confederacies and the pacification of larger pockets of territory, as well as the gradual abandonment of ultraviolent practices by tribes outside of these confederacies. More critical historians question whether the Lawful Commonwealth was truly the originator of the Four Rites and Four Precepts, or merely one of many adoptor societies of constructive innovations that arose elsewhere. What is certain is that multiple neolithic polities would claim the legacy of the Lawful Commonwealth, adopting its foundational narratives to legitimise their own rule and absorbing its laws as part of their own culture and custom.