Administrative divisions of Cartadania and Yonderian Peasants' War: Difference between pages

Tag: 2017 source edit |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ | For other peasant revolts, see [[List of peasant revolts]]. | ||

The | {{Infobox military conflict | ||

| conflict = Yonderian Peasants' War | |||

| width = | |||

| partof = | |||

| image = File:Wandering Bands of Insurgents during the German Peasants War.jpg | |||

| image_size = | |||

| alt = | |||

| caption = The Peasant Army marching past the burning city Carre | |||

| date = 1641-1643 | |||

| place = Parts of [[Yonderre]], especially the counties [[Amarre]], [[Donne]] and [[Kubagne]] | |||

| coordinates = <!--Use the {{coord}} template --> | |||

| map_type = | |||

| map_relief = | |||

| map_size = | |||

| map_marksize = | |||

| map_caption = | |||

| map_label = | |||

| territory = | |||

| result = Suppression of revolt and execution of its leaders | |||

| status = | |||

| combatants_header = | |||

| combatant1 = Peasant Army | |||

| combatant2 = [[Knight of the Realm|Knights of the Realm]]<br>Raised levies | |||

| combatant3 = | |||

| commander1 = [[Fabian Löwenschiold]] '''†''' <br>[[Michael von Bromstadt]] '''†''' <br>[[Erich von der Heydte]] '''†''' <br>[[Sören Vergelter]] {{Executed}} <br>[[Richard de Blaise]] {{Executed}} | |||

| commander2 = [[Auguste II de Houicourt]]<br>[[Louis d'Arconne]]<br>[[Florian von Bromstadt]] | |||

| commander3 = | |||

| units1 = | |||

| units2 = | |||

| units3 = | |||

| strength1 = 300,000 | |||

| strength2 = 4,500 (initially)<br>12,500 - 16,000 | |||

| strength3 = | |||

| casualties1 = >100,000 | |||

| casualties2 = Minimal | |||

| casualties3 = | |||

| notes = | |||

| campaignbox = | |||

}} | |||

The '''Yonderian Peasants' War''' ([[Burgoignesc language|Burgoignesc]]: ''Guerre des Paysans Yonderre'', East Gothic: ''Yondersche Bauernkrieg''), '''Great Peasants' War''' or '''Great Peasants' Revolt''' was a widespread popular revolt led by disgruntled [[Knight of the Realm|Knights of the Realm]] against the [[Yonderre|Yonderian]] nobility. The leader of the revolt, [[Knight of the Realm]] [[Fabian Löwenschiold]] dreamed of founding a democratic republic in the area, envisaging the abolition of the [[Catholic Church]] and its rituals, replaced by a faith based on a direct contact with God through the personal interpretation of Scripture. He also envisioned a utopian elimination of titles of nobility, the nationalization of land and mines, the establishment of schools, hospitals and old people’s homes. | |||

The war began with separate insurrections in [[Donne]] and [[Kubagne]] and soon spread to [[Amarre]]. In mounting their insurrection, the peasants faced insurmountable obstacles. The democratic nature of their movement left them without a command structure and they lacked artillery and cavalry. Most of them had little, if any, military experience. In combat they often turned and fled, and were massacred by their pursuers. Their opposition had experienced military leaders as well as well-equipped and disciplined soldiers. | |||

The revolt incorporated some principles and rhetoric from the Protestant Reformation through which the peasants sought influence and freedom, and much of the conflict echoed the [[Great Confessional War]]. Historians have interpreted the economic aspects of the Yonderian Peasants' War differently, and social and cultural historians continue to disagree on its causes and nature. | |||

== Background == | |||

[[File:Gustav Adolf Closs Ritter 1896.jpg|thumb|left|Mustering of the [[Knight of the Realm|Knights of the Realm]]]] | |||

The revolt happened in a time of great social and ethnic inequality in [[Yonderre]]. The mostly [[East Goths|Gothic]] peasants felt disconnected from their mostly [[Bergendii]] rulers and were growing discontent with their serfdom. An element of the conflict drew simply on resentment toward the nobility. A band of [[Knight of the Realm|Knights of the Realm]], lead by [[Fabian Löwenschiold]], took the side of the peasants. The conflict echoed the [[Great Confessional War]] in many aspects, with much shared in principles and rhetoric. | |||

Historians disagree on the nature of the revolt and its causes, whether it grew out of the emerging religious controversy centered on protestantism; whether a wealthy tier of peasants saw their own wealth and rights slipping away, and sought to weave them into the legal, social and religious fabric of society; or whether peasants objected to the emergence of a modernizing, centralizing nation state. | |||

One view is that the origins of the Yonderian Peasants' War lay partly in the unusual power dynamic caused by the agricultural and economic dynamism of the previous decades. Labor shortages in the last half of the sixteenth century had allowed peasants to sell their labor for a higher price; food and goods shortages had allowed them to sell their products for a higher price as well. Consequently, some peasants, particularly those who had limited allodial requirements, were able to accrue significant economic, social, and legal advantages. Peasants were more concerned to protect the social, economic and legal gains they had made than about seeking further gains. | |||

Communist thinker [[Thibaut de Berre]] interpreted the war as a case in which an emerging proletariat urban class failed to assert a sense of its own autonomy in the face of dukely power and left the rural classes to their fate. | |||

== Outbreak == | |||

Several smaller revolts broke out simultaneously but seperately in [[Donne]] and [[Kubagne]] in the late Summer of 1641. These soon banded together under Fabian Löwenschiold, an ethnically [[East Goths|Gothic]] [[Knight of the Realm]] from Donnebourg. Some other Knights of the Realm also joined [[Löwenschiold]] army that became known as "the Black Host" ([[Burgoignesc language|Burgoignesc]]: ''la Foule Noire'', East Gothic: ''der Schwarze Haufen'') for the black banner carried by Löwenschiold. | |||

{{ | == Course of the war == | ||

=== Sacking of Carre === | |||

{{main|Sacking of Carre}} | |||

The first action of the newly assembled Black Host was to sack the town of [[Carre]] in Eastern [[Kubagne]] in October of 1641. Carre was the seat of a bishopric and home to Carre Church. The Black Host burnt the church and pillaged the town, raping and killing countless innocent people, much to the dismay of their leadership. Löwenschiold, who had given the order to march to Carre but had stayed outside the town was reportedly devastated when he he recieved the news and galloped into town to reinstill discipline. When news broke of the fate of Carre it became a turning point in the general public's view of the revolt, with many who were previously sympathetic to the rebels now turning their backs on them. | |||

== | === Siege of Toubourg === | ||

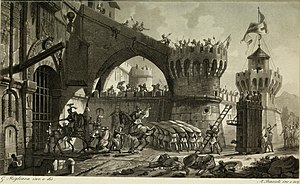

[[File:Storia ed analisi degli antichi romanzi di cavalleria e dei poemi romanzeschi d'Italia - con dissertazioni sull'origine, sugl'istituti, sulle cerimonie de' cavalieri, sulle corti d'amore, sui tornei, (14783615993).jpg|thumb|The Black Host attempting to storm Toubourg]] | |||

{{main|Siege of Toubourg}} | |||

The Black Host laid siege to Toubourg over the winter of 1641/1642. The walled city of Toubourg was rich in gold and arms, both of which the Black Host lacked. Because they lacked artillery, the Black Host had little choice but to attempt to starve the town, and so they camped around the town until early spring. They had arrived too late however as the year's harvest had already been secured by the Toubourgers who were able to hunker down safely behind their walls. Toubourg's defending force was modestly sized compared to the large rebel army at their doorstep but their strength was multiplied greatly by the protective walls of the city that denied the Black Host entry. | |||

Sensing that his army was becoming restless and fearing the probable arrival of reinforcements for the Toubourgers, [[Löwenschiold]] ordered that the town be stormed on February 18th. The assault was unsuccesful however and the Black Host had to abandon the siege, marching west towards [[Kubagne]] to meet with volunteers to bolster their numbers. | |||

=== Massacre at Breitenfeld === | |||

[[File:Rohrbach-verbrennung-1525.jpg|thumb|Rebel leader [[Sören Vergelter]] is burnt at the stake]] | |||

{{main|Massacre at Breitenfeld}} | |||

In early March of 1642 the army under [[Grand Duke of Yonderre|Grand Duke]] [[Auguste II de Houicourt]] caught up with the Black Host on the wide fields of Breitenfeld. The [[Grand Duke of Yonderre|Grand Duke]]'s army dealt the Black Host a catastrophic blow in the battle that followed on the 9th of March. The [[Grand Duke of Yonderre|Grand Duke]]'s troops included close to 6,000 [[Knight of the Realm|Knights of the Realm]]. As such they were experienced, well-equipped, well-trained and of good morale. The peasants, on the other hand, had poor, if any, equipment, and many had neither experience nor training. Many of the peasants disagreed over whether to fight or negotiate. | |||

de Hoicourt's army started a heavy combined infantry, cavalry and artillery attack at midday. The peasants were caught off-guard and fled in panic to the town, followed and continuously attacked by the [[Grand Duke of Yonderre|Grand Duke]]'s forces. Many of the rebels present were slain in what turned out to be a massacre. Casualty figures are unreliable but estimates range from 3,000 to 10,000 while the casualties of the Knights were as few as six, two of whom were only wounded. [[Sören Vergelter]], one of the leaders of the uprising, was captured, tortured and executed at [[Toubourg]] on the 12th of March. | |||

The Massacre at Breitenfeld was a disastrous defeat for the Peasant army, whose morale deteriorated to such a point that the Black Host largely dissolved following the battle. [[Löwenschiold]] fled in shame with the remains of his army to the [[Black Forest]] from where they would mount periodic raids on nearby towns. | |||

=== Battle of Stonne === | |||

[[File:Lovis Corinth 009.jpg|thumb|''Last stand of Fabian Löwenschiold'', oil on canvas by [[Louen d'Everard]]]] | |||

{{main|Battle of Stonne}} | |||

In February of 1643, almost a year after the Massacre at Breitenfeld, the army under [[Grand Duke of Yonderre|Grand Duke]] Auguste II de Houicourt caught up with the Black Host once more in the [[Black Forest]]. After brief skirmishes in the woods themselves the peasants withdrew to the nearby town of [[Stonne]] wherein they occupied several buildings, fortifying them with what they had at hand. de Hoicourt's army surrounded the village and sent in to negotiate Florian von Bromstadt, [[Knight of the Realm]] and brother to Michael von Bromstadt, one of the rebel leaders. The peacemaking went nowhere however and Florian von Bromstadt returned to his camp empty-handed. de Hoicourt decided to storm the town the next day and laid the plans to do so with his commander Louis d'Arconne. | |||

== | The peasant force, no stronger than a thousand, had holed up in several buildings in Stonne including its church and manor. The peasants were split on what to do. Some saw their inevitable defeat at the hands of de Houicourt's army as a form of martyrdom, while others saw it as needless and hopeless. Some deserted, voluntarily walking into captivity, while others tried to sneak out under the cover of night. | ||

=== | |||

=== | The assault began in the morning hours, with de Houicourt's men fighting house to house and room to room to evict the peasants. Fabian Löwenschiold, the figurehead of the revolution, refused several pleas to surrender and fought his last stand in the town manor, holding the tattered banner of his revolution with one hand as he fought with the other. After fighting off and killing several foes [[Löwenschiold]] was finally felled by his old friend Louis d'Arconne personally. Richard de Blaise, final leader of the rebellion, surrendered along with his men in the church. de Blaise was hanged in Donnebourg five weeks later, in April of 1643. | ||

[[Category: | == Ultimate failure of the rebellion == | ||

[[Category: | [[File:The story history of France from the reign of Clovis, 481 A.D., to the signing of the armistice, November, 1918 (1919) (14753795186).jpg|thumb|The hanging of [[Richard de Blaise]]]] | ||

[[Category: | The main causes of the failure of the rebellion was the lack of communication between the peasant bands because of territorial divisions, and because of their military inferiority. While some [[Knight of the Realm|Knights of the Realm]] and professional soldiers joined the peasants, the armies of the [[Grand Duke of Yonderre|Grand Duke]] had a better grasp of military technology, strategy and more experience. The aftermath of the Yonderian Peasants' War led to an overall reduction of rights and freedoms of the peasant class, effectively pushing them out of Yonderre's political life. The overall goals of change for these peasants had failed to come to pass and would remain largely stagnant until the [[Yonderian Golden Age]]. | ||

== Legacy == | |||

=== Formation of the Grand Ducal Army and Custodes Yonderre === | |||

The Peasants' War highlighted several issues with the [[Yonderre|Yonderian]] system of [[Knight of the Realm|Knights of the Realm]]. The reliance on a relatively small but elite standing army was still viewed as a sufficient deterent to foreign invaders but had proven to be wholly inadequate in stopping a large scale internal revolt that saw the Knights spread too thin to cover everything. It was also highly problematic that the majority of the rebel leadership had come from the ranks of the [[Knight of the Realm|Knights of the Realm]]. | |||

Very shortly after the war [[Grand Duke of Yonderre|Grand Duke]] [[Auguste II de Houicourt]] set about drawing up the plan for a new system of armed forces for [[Yonderre]] alongside his commander Louis d'Arconne. The [[Custodes Yonderre]] was formed in 1643 as a police force to maintain law and order in major cities, while the plans for a new system of armed forces were finalized the next Summer. Thus on the 10th of June 1644, on what would have been the 208th birthday of Yonderre's first Grand Count [[Joanus de Martigueux]], the [[Yonderian Defence Force#Grand Ducal Army|Grand Ducal Army]] was sworn in with the reorganization of the [[Knight of the Realm|Knights of the Realm]] into the [[Guard Cuirassier Division#Ducal%20Lifeguard%20of%20Horse|Ducal Lifeguard of Horse]] and the raising of several infantry, cavalry and artillery regiments. | |||

=== In culture === | |||

The Yonderian Peasants' War has featured heavily in Yonderian culture, particularly after the advent of Yonderian national romanticism in the nineteenth century. The marching songs of the rebels remain popular drinking songs in Gothic-speaking [[Yonderre]] in particular. Notably, [[Dom Martinez]] recorded ''Don Martinez sings rebel songs of the Peasants' War'' in 1953 which became a cultural phenomenon in [[Yonderre]] and rekindled interest in the conflict in the general public. Many films and TV series have been made about the Yonderian Peasants' War. The rebel leaders and particularly [[Fabian Löwenschiold]] are paradoxically revered as martyrs to the causes of both the far left Yonderian Workers' Party and the far right Gothic People's Party. Playwright [[Hieronymus d'Olbourg]] wrote ''Löwenschiold'' in 1835 during the [[Yonderian Golden Age]], a play centred on the events of the Yonderian Peasants' War with Löwenschiold as the protagonist. | |||

Communist thinker [[Thibaut de Berre]] interpreted the war as a case in which an emerging proletariat urban class failed to assert a sense of its own autonomy in the face of dukely power and left the rural classes to their fate. From this he extrapolated that the war was in fact a very early example of a communist uprising, albeit a failed one and one that caused great damage to the cause. | |||

== See also == | |||

* [[Great Confessional War]] | |||

* [[List of peasant revolts]] | |||

* [[Knight of the Realm]] | |||

[[Category:Yonderre]] | |||

[[Category:Wars]] | |||

[[Category:Canonical Article]] | |||

Latest revision as of 15:56, 3 October 2023

For other peasant revolts, see List of peasant revolts.

| Yonderian Peasants' War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The Peasant Army marching past the burning city Carre | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Peasant Army |

Knights of the Realm Raised levies | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Fabian Löwenschiold † Michael von Bromstadt † Erich von der Heydte † Sören Vergelter Richard de Blaise |

Auguste II de Houicourt Louis d'Arconne Florian von Bromstadt | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 300,000 |

4,500 (initially) 12,500 - 16,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| >100,000 | Minimal | ||||||

The Yonderian Peasants' War (Burgoignesc: Guerre des Paysans Yonderre, East Gothic: Yondersche Bauernkrieg), Great Peasants' War or Great Peasants' Revolt was a widespread popular revolt led by disgruntled Knights of the Realm against the Yonderian nobility. The leader of the revolt, Knight of the Realm Fabian Löwenschiold dreamed of founding a democratic republic in the area, envisaging the abolition of the Catholic Church and its rituals, replaced by a faith based on a direct contact with God through the personal interpretation of Scripture. He also envisioned a utopian elimination of titles of nobility, the nationalization of land and mines, the establishment of schools, hospitals and old people’s homes.

The war began with separate insurrections in Donne and Kubagne and soon spread to Amarre. In mounting their insurrection, the peasants faced insurmountable obstacles. The democratic nature of their movement left them without a command structure and they lacked artillery and cavalry. Most of them had little, if any, military experience. In combat they often turned and fled, and were massacred by their pursuers. Their opposition had experienced military leaders as well as well-equipped and disciplined soldiers.

The revolt incorporated some principles and rhetoric from the Protestant Reformation through which the peasants sought influence and freedom, and much of the conflict echoed the Great Confessional War. Historians have interpreted the economic aspects of the Yonderian Peasants' War differently, and social and cultural historians continue to disagree on its causes and nature.

Background

The revolt happened in a time of great social and ethnic inequality in Yonderre. The mostly Gothic peasants felt disconnected from their mostly Bergendii rulers and were growing discontent with their serfdom. An element of the conflict drew simply on resentment toward the nobility. A band of Knights of the Realm, lead by Fabian Löwenschiold, took the side of the peasants. The conflict echoed the Great Confessional War in many aspects, with much shared in principles and rhetoric.

Historians disagree on the nature of the revolt and its causes, whether it grew out of the emerging religious controversy centered on protestantism; whether a wealthy tier of peasants saw their own wealth and rights slipping away, and sought to weave them into the legal, social and religious fabric of society; or whether peasants objected to the emergence of a modernizing, centralizing nation state.

One view is that the origins of the Yonderian Peasants' War lay partly in the unusual power dynamic caused by the agricultural and economic dynamism of the previous decades. Labor shortages in the last half of the sixteenth century had allowed peasants to sell their labor for a higher price; food and goods shortages had allowed them to sell their products for a higher price as well. Consequently, some peasants, particularly those who had limited allodial requirements, were able to accrue significant economic, social, and legal advantages. Peasants were more concerned to protect the social, economic and legal gains they had made than about seeking further gains.

Communist thinker Thibaut de Berre interpreted the war as a case in which an emerging proletariat urban class failed to assert a sense of its own autonomy in the face of dukely power and left the rural classes to their fate.

Outbreak

Several smaller revolts broke out simultaneously but seperately in Donne and Kubagne in the late Summer of 1641. These soon banded together under Fabian Löwenschiold, an ethnically Gothic Knight of the Realm from Donnebourg. Some other Knights of the Realm also joined Löwenschiold army that became known as "the Black Host" (Burgoignesc: la Foule Noire, East Gothic: der Schwarze Haufen) for the black banner carried by Löwenschiold.

Course of the war

Sacking of Carre

The first action of the newly assembled Black Host was to sack the town of Carre in Eastern Kubagne in October of 1641. Carre was the seat of a bishopric and home to Carre Church. The Black Host burnt the church and pillaged the town, raping and killing countless innocent people, much to the dismay of their leadership. Löwenschiold, who had given the order to march to Carre but had stayed outside the town was reportedly devastated when he he recieved the news and galloped into town to reinstill discipline. When news broke of the fate of Carre it became a turning point in the general public's view of the revolt, with many who were previously sympathetic to the rebels now turning their backs on them.

Siege of Toubourg

The Black Host laid siege to Toubourg over the winter of 1641/1642. The walled city of Toubourg was rich in gold and arms, both of which the Black Host lacked. Because they lacked artillery, the Black Host had little choice but to attempt to starve the town, and so they camped around the town until early spring. They had arrived too late however as the year's harvest had already been secured by the Toubourgers who were able to hunker down safely behind their walls. Toubourg's defending force was modestly sized compared to the large rebel army at their doorstep but their strength was multiplied greatly by the protective walls of the city that denied the Black Host entry.

Sensing that his army was becoming restless and fearing the probable arrival of reinforcements for the Toubourgers, Löwenschiold ordered that the town be stormed on February 18th. The assault was unsuccesful however and the Black Host had to abandon the siege, marching west towards Kubagne to meet with volunteers to bolster their numbers.

Massacre at Breitenfeld

In early March of 1642 the army under Grand Duke Auguste II de Houicourt caught up with the Black Host on the wide fields of Breitenfeld. The Grand Duke's army dealt the Black Host a catastrophic blow in the battle that followed on the 9th of March. The Grand Duke's troops included close to 6,000 Knights of the Realm. As such they were experienced, well-equipped, well-trained and of good morale. The peasants, on the other hand, had poor, if any, equipment, and many had neither experience nor training. Many of the peasants disagreed over whether to fight or negotiate.

de Hoicourt's army started a heavy combined infantry, cavalry and artillery attack at midday. The peasants were caught off-guard and fled in panic to the town, followed and continuously attacked by the Grand Duke's forces. Many of the rebels present were slain in what turned out to be a massacre. Casualty figures are unreliable but estimates range from 3,000 to 10,000 while the casualties of the Knights were as few as six, two of whom were only wounded. Sören Vergelter, one of the leaders of the uprising, was captured, tortured and executed at Toubourg on the 12th of March.

The Massacre at Breitenfeld was a disastrous defeat for the Peasant army, whose morale deteriorated to such a point that the Black Host largely dissolved following the battle. Löwenschiold fled in shame with the remains of his army to the Black Forest from where they would mount periodic raids on nearby towns.

Battle of Stonne

In February of 1643, almost a year after the Massacre at Breitenfeld, the army under Grand Duke Auguste II de Houicourt caught up with the Black Host once more in the Black Forest. After brief skirmishes in the woods themselves the peasants withdrew to the nearby town of Stonne wherein they occupied several buildings, fortifying them with what they had at hand. de Hoicourt's army surrounded the village and sent in to negotiate Florian von Bromstadt, Knight of the Realm and brother to Michael von Bromstadt, one of the rebel leaders. The peacemaking went nowhere however and Florian von Bromstadt returned to his camp empty-handed. de Hoicourt decided to storm the town the next day and laid the plans to do so with his commander Louis d'Arconne.

The peasant force, no stronger than a thousand, had holed up in several buildings in Stonne including its church and manor. The peasants were split on what to do. Some saw their inevitable defeat at the hands of de Houicourt's army as a form of martyrdom, while others saw it as needless and hopeless. Some deserted, voluntarily walking into captivity, while others tried to sneak out under the cover of night.

The assault began in the morning hours, with de Houicourt's men fighting house to house and room to room to evict the peasants. Fabian Löwenschiold, the figurehead of the revolution, refused several pleas to surrender and fought his last stand in the town manor, holding the tattered banner of his revolution with one hand as he fought with the other. After fighting off and killing several foes Löwenschiold was finally felled by his old friend Louis d'Arconne personally. Richard de Blaise, final leader of the rebellion, surrendered along with his men in the church. de Blaise was hanged in Donnebourg five weeks later, in April of 1643.

Ultimate failure of the rebellion

The main causes of the failure of the rebellion was the lack of communication between the peasant bands because of territorial divisions, and because of their military inferiority. While some Knights of the Realm and professional soldiers joined the peasants, the armies of the Grand Duke had a better grasp of military technology, strategy and more experience. The aftermath of the Yonderian Peasants' War led to an overall reduction of rights and freedoms of the peasant class, effectively pushing them out of Yonderre's political life. The overall goals of change for these peasants had failed to come to pass and would remain largely stagnant until the Yonderian Golden Age.

Legacy

Formation of the Grand Ducal Army and Custodes Yonderre

The Peasants' War highlighted several issues with the Yonderian system of Knights of the Realm. The reliance on a relatively small but elite standing army was still viewed as a sufficient deterent to foreign invaders but had proven to be wholly inadequate in stopping a large scale internal revolt that saw the Knights spread too thin to cover everything. It was also highly problematic that the majority of the rebel leadership had come from the ranks of the Knights of the Realm.

Very shortly after the war Grand Duke Auguste II de Houicourt set about drawing up the plan for a new system of armed forces for Yonderre alongside his commander Louis d'Arconne. The Custodes Yonderre was formed in 1643 as a police force to maintain law and order in major cities, while the plans for a new system of armed forces were finalized the next Summer. Thus on the 10th of June 1644, on what would have been the 208th birthday of Yonderre's first Grand Count Joanus de Martigueux, the Grand Ducal Army was sworn in with the reorganization of the Knights of the Realm into the Ducal Lifeguard of Horse and the raising of several infantry, cavalry and artillery regiments.

In culture

The Yonderian Peasants' War has featured heavily in Yonderian culture, particularly after the advent of Yonderian national romanticism in the nineteenth century. The marching songs of the rebels remain popular drinking songs in Gothic-speaking Yonderre in particular. Notably, Dom Martinez recorded Don Martinez sings rebel songs of the Peasants' War in 1953 which became a cultural phenomenon in Yonderre and rekindled interest in the conflict in the general public. Many films and TV series have been made about the Yonderian Peasants' War. The rebel leaders and particularly Fabian Löwenschiold are paradoxically revered as martyrs to the causes of both the far left Yonderian Workers' Party and the far right Gothic People's Party. Playwright Hieronymus d'Olbourg wrote Löwenschiold in 1835 during the Yonderian Golden Age, a play centred on the events of the Yonderian Peasants' War with Löwenschiold as the protagonist.

Communist thinker Thibaut de Berre interpreted the war as a case in which an emerging proletariat urban class failed to assert a sense of its own autonomy in the face of dukely power and left the rural classes to their fate. From this he extrapolated that the war was in fact a very early example of a communist uprising, albeit a failed one and one that caused great damage to the cause.