Phillipe d'Everard (paleontologist): Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary Tag: 2017 source edit |

Tag: 2017 source edit |

||

| Line 133: | Line 133: | ||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

* [[House d'Everard]] | |||

* [[Thibault d'Avignon]] | * [[Thibault d'Avignon]] | ||

* [[Paleontology in Yonderre]] | * [[Paleontology in Yonderre]] | ||

* [[History of paleontology]] | * [[History of paleontology]] | ||

* [[Greater Levantine Formation]] | * [[Greater Levantine Formation]] | ||

* [[Joanusaurid]] | |||

* ''[[Caphirosaurus]]'' | * ''[[Caphirosaurus]]'' | ||

* ''[[Joanusaurus]]'' | * ''[[Joanusaurus]]'' | ||

Revision as of 14:39, 30 October 2023

Professor Doctor Baron Phillipe Edmond d'Everard | |

|---|---|

d'Everard in 1918 | |

| Born | October 22, 1865 |

| Died | February 2, 1938 (aged 72) |

| Cause of death | Complications associated with pneumonia |

| Nationality | Yonderian |

| Alma mater | University of Collinebourg |

| Occupation | Paleontology, zoology, herpetology |

| Years active | 1884-1938 |

| Spouse(s) | Hedvig d'Everard (née Schmidt) (1876–1962) |

| Children | Rachet d'Everard (1903–1997) Sophie d'Everard (1907–2002) |

| Parent(s) | Rachet d'Everard (physicist) (1838–1922) Louise d'Everard (1843–1940) |

| Relatives | See d'Everard family |

| Awards | Order of the Kestrel |

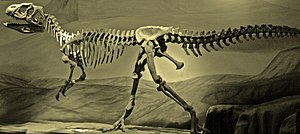

Professor Doctor Baron Phillipe Edmond d'Everard OC (October 22, 1865 – February 2, 1938) was a highly influential Yonderian paleontologist of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He became world-famous after excavating and describing the first recognized remains of the Caphirosaurus in 1900 in Belactrum, Caphiria, elevating the world of paleontology from the world of academia to the public eye. His further discoveries and categorisation of more than 200 species of extinct lifeforms has earned him the moniker "Father of paleontology", complimenting Thibaut d'Avignon's moniker "Grandfather of paleontology".

d'Everard was a prodigious writer, with 1,400 papers published over his lifetime. A lifelong and highly dedicated field worker, d'Everard died suddenly from complications associated with pneumonia 72 years old on February 2, 1938 in Lariana, Talionia, while leading a paleontological expedition. His proposal for the origin of mammalian molars is notable among his theoretical contributions. "d'Everard's rule", however, the hypothesis that mammalian lineages gradually grow larger over geologic time, while named after him, is "neither explicit nor implicit" in his work.[1]

The joanusaurid dinosaur Everardtadens and ceratopsian dinosaur Everardceratops are both named in honour of d'Everard. Phillipe d'Everard was head of the House d'Everard from his father Rachet d'Everard's death in 1922 until his own in 1938. His son was the Marshal of Yonderre Rachet d'Everard (1903-1997) and his only daughter the acclaimed ballet dancer Sophie d'Everard (1907-2002).

Biography

Early life, education and first expeditions

Phillipe Edmond d'Everard was born on October 22, 1865, as the eldest son of famed physicist Rachet d'Everard (1838–1922) and his wife Louise, née d'Auguste (1843–1940). Phillipe harboured a strong interest in natural science from an early age and kept several exotic animals as pets. He attended a private Catholic boys school in Sainte-Catherine operated by the Order of St. Prokop. He explored pits and quarries in the surrounding areas, discovering ammonites, shells of sea urchins, fish bones, coral, and worn-out remains of dead animals. Reaching 18 years of age, d'Everard served his conscription with the 11th Infantry Division of the Yonderian Army from 1883-84 during which time he was known to his comrades as "Eddie" due to there being five men named Phillipe in his company.

Returning from the army, d'Everard enrolled with the University of Collinebourg studying biology from 1884-89. One of d'Everard's courses was taught by paleontologist Thibaut d'Avignon who had described Joanusaurus a few years prior. d'Everard was invited to partake in digs in the field seasons of 1887-92 under d'Avignon's supervision. d'Everard partook in the 1891 and 1892 excavations in Vollardie that led to the discovery of the most complete Vollardisaurus skeletons known at the time. d'Everard returned to the University of Collinebourg in 1892 to work on his thesis, published in 1895 as "Evolutionary development and traits in derived Joanusaurids".[2]

Discovery of Caphirosaurus, First Great War and professorate

In May of 1900, d'Everard led an expedition to Caphiria, the first such undertaken since the beginning of the First Great War. Funded in part by his family fortune and in part by the University of Collinebourg, the expedition conducted digs in eastern Belactrum. While excavating, d'Everard's expedition excavated the most complete partial skeleton of C. imperator yet. Writing at the time d'Everard said "Quarry No. 1 contains the lower jaw, femur, pubes, humerus, three vertebrae and two undetermined bones of a large Carnivorous Dinosaur not described by d'Avignon... I have never seen anything like it from the Cretaceous". d'Everard mailed sketches and photo negatives of the bones to d'Avignon in Collinebourg, who concurred that d'Everard had indeed discovered a new species.

d'Everard returned to Collinebourg with his discoveries in September of 1900 and began describing his findings. Due to developments in the First Great War, d'Everard's planned field expedition to return to Belactrum had to be postponed to the following year. In the meantime, d'Everard took up a lecturate at the University of Collinebourg, and while there named and described several fossilized amphibians including Belactrobatrachus that he had excavated from Caphiria. It was also around this time d'Everard began his work on what would eventually become his description of the Caphirosaurus. In May of 1902 d'Everard once more mounted an expedition to Caphiria, excavating in and around Serracene, Meceria. d'Everard's team uncovered a more complete partial skeleton of Caphirosaurus outside Serracene in 1902, comprising approximately 36 fossilized bones including a premaxilla and complete lower jaw, both with teeth in situ.

Based on his newest finds from Serracene, d'Everard was able to complete and publish his description of the new theropod which he named Caphirosaurus imperator. Based on his finds from 1900 and 1902, d'Everard also reclassified shed teeth discovered by d'Avignon in 1874 and Krankos' post cranial elements from 1894 as being Caphirosaurus remains. The generic name is derived from the name of the country in which it was discovered, Caphiria, and the Istroyan word σαῦρος (sauros, meaning "lizard"). d'Everard used the Latin word imperator, meaning "emperor", for the specific name. The full binomial therefore translates to "Caphirian lizard emperor" or "Emperor Lizard of Caphiria", emphasizing the animal's size and perceived dominance over other species of the time.[3] The paper and subsequent press conference and lectures received substantial press coverage, much more so than before seen in paleontology, and is credited by many to have elevated the world of paleontology from academia to the public eye.[4]

d'Everard continued to teach extinct zoology at the University of Collinebourg, giving lectures, teaching classes and performing presentations of new species he described. d'Everard organized several student digs in Yonderre throughout the 1900s and 10s, particularly to the mountains of Vollardie, from which numerous extinct species of amphibians and fish were discovered as well as some new dinosaurs like the Compsognathid Coopgnathus and early ceratopsian Avonceratops.

Iscastan expeditions and 1920s

d'Everard finally returned to Caphiria in 1919 to continue his field work in Sarpedon. In June of 1919, the expedition led by d'Everard uncovered remains of Joanusaurus in the Aravera mountains of the Caphirian province Iscasta, the first find of Joannusaurus outside Levantia. d'Everard initially viewed the specimen as a subadult J. davignoni, but upon closer inspection it was recategorized as a new subspecies, J. iscastae. J. iscastae differs from J. davignoni by its longer snout and smaller physical stature, findings that d'Everard published in his December of 1919 monograph "Caphirian Joanusaurs".[5] Based on scholarly consensus and the somewhat limited knowledge of paleobiology and paleodiversity in late-Jurassic and early Cretaceous Sarpedon (as part of Sarpolevantia), d'Everard surmised that Joanusaurs were probably apex predators in present day Caphiria such as they had been shown to be in and around the Greater Levantine Formation.

d'Everard fielded several further expeditions to Iscasta throughout the 1920s, excavating numerous new species of dinosaurs, fish and reptillians. d'Everard took part in the 1925 expedition to Cesindes led by paleontologist duo Jour & Leon, which uncovered another partial Caphirosaurus skeleton, about 25% complete. Initially described as a new genus with the name Imperatorsaurus, it was soon recognized as a subspecies of Caphirosaurus with the aid of d'Everard and given the name C. caesar.[6] d'Everard began alternating annually between field seasons and lecturing at the University of Collinebourg from the late 1920s until his death.

Final expeditions and death

Despite the on-going Second Great War and against his wife's wishes, d'Everard hired a team and funded an expedition to Talionia out of his own pocket in 1937. After lengthy negotiations with the local government, d'Everard's team was permitted to dig north of Lariana in June of 1937. Initial finds were mostly of crocodillomorphs, the description of one of which, Larianasuchops, was published posthumously, written mostly by d'Everard.[7] Traces fossils of Caphirosaurus including footprints were discovered in July, while most of a femur and some vertebrae of a Caphirosaurus were found in early August. The team continued to excavate fossils of small mammals and amphibians throughout the field season. A partial Testudosaurus was discovered by chance in a hillside, discovered to be nearly 60% complete once excavated by the middle of September.

Due to the on-going war however, d'Everard's team was unable to return to Yonderre for the time being and forced to remain in Talionia for the winter. The fossil haul was stored away under armed guard in Lariana and d'Everard and his team set up temporary offices in a hotel downtown to begin describing the specimens. d'Everard fell ill with pneumonia in December of 1937 and became at times delirious. He continued his work however, aided by his team, and continued to describe and categorize specimens. d'Everard started experiencing lucid fever dreams in January of 1938. When he read in a letter in late January that his son Rachet had been wounded fighting for the Burgoignesc Foreign Legion, d'Everard muttered that it was preposterous that the Burgoignesc would allow boys as young as Rachet to fight.[8] The bedridden Phillipe d'Everard died in his sleep and was found by his aide in the morning of Februaury 2nd, 1938. His still body still clutched a half-full glass of Burgoignesc Xerie in the left hand, d'Arvinne's On the Origin of Species was open on his stomach and he was still wearing reading glasses.

d'Everard's body was prepared by a local mortician and shipped home to Yonderre in April of 1938. His wife had been informed by letter of condolence from d'Everard's aide in the middle of February as well as the Rector of the University of Collinebourg Joanus Lavreau. For his contributions to science throughout the last half-century, d'Everard was granted a state funeral held in Collinebourg attended by thousands including Grand Duke of Yonderre Joanus X de Martigueux. d'Everard was buried in Sainte-Catherine, Kubagne. Most of his personal collection of fossils and knick knacks was given away to the University of Collinebourg and museums around Yonderre following his death.

Personality and views

Personality and views on evolution

d'Everard was described by colleagues as a peerless if headstrong academic with a neverending appetite for discovery. His son Rachet d'Everard described him as "stern, but fair - a man dedicated to his work".[9] d'Everard smoked a pipe his entire adult life, a trait that became iconic to the public perception of him. d'Everard was prompted to do so by his Sergeant while serving with the Yonderian Army in 1884, on the grounds that the pipe was more gentlemanly than the cigarette. d'Everard's mentor Thibault d'Avignon described d'Everard in a letter to the former's cousin as "both genial and always interesting, easily approachable, and both kindly and helpful".

As a young man, d'Everard read d'Arvinne's On the Origin of Species which largely shaped his understanding of evolution, of which he published his own "Origin of the Fittest: Essays in Evolution" in 1914.[10] d'Everard was a lifelong proponent of the now-widely accepted theory that modern birds are derived theropod dinosaurs, a hotly debated topic in his lifetime. When asked during a lecture in 1912 if anything could be gleamed from evolution as the product of a Creator or indeed divine intervention, d'Everard surmised that "[t]he Creator must be inordinately fond of beetles", stating that "the earth is home to endless million different species of them".

Personal life

Phillipe d'Everard married the eleven years younger Hedvig Schmidt (1876-1962), a Toubourg native, in 1894. The couple had three children, Marshal of Yonderre Rachet d'Everard (1903-1997), ballet dancer Sophie d'Everard (1907-2002) and the stillborn Killian d'Everard (1909). When not on expeditions, the d'Everards lived chiefly in the d'Everard Bourg in Sainte-Catherine, although Phillipe frequently spent nights in dormitories provided by the University of Collinebourg during his professorate.

Legacy

In fewer than 55 years as a scientist, d'Everard published over 1,400 scientific papers, a record that is rivaled by few other scientists. Having discovered and described more than 200 extinct lifeforms, d'Everard bears the monicker "father of paleontology" in academic circles.[11][12] Although d'Everard is chiefly known as a paleontologist having discovered at least 56 new dinosaur species, his contributions extended to ichthyology and herpetology, in which he catalogued 300 species of fishes and described over 300 species of reptiles over three decades.

"d'Everard's rule", suggesting that mammalian lineages gradually grow larger over geologic time, while named after him, is "neither explicit nor implicit" in his work according to modern paleontologists.[13]

The joanusaurid dinosaur Everardtadens and ceratopsian dinosaur Everardceratops are both named in honour of d'Everard, as are the specific names of several species of salamanders and amphibians. The Testudosaurus discovered by d'Everard's team in Talionia in 1937 is nicknamed "Phillipe" after him.

The Primo Kino movie Swallowing Dust from 2008 is a dramatization of d'Everard's final expedition to Talionia, with Jean-Yves Forvert playing the role of d'Everard.

See also

- House d'Everard

- Thibault d'Avignon

- Paleontology in Yonderre

- History of paleontology

- Greater Levantine Formation

- Joanusaurid

- Caphirosaurus

- Joanusaurus

- Everardtadens

- Everardceratops

- Rattusfukus

Notes

- ↑ Fürster, Johann: Mammalian derivation of the Permian period, pg. 11-14. 1999.

- ↑ d'Everard, Phillipe E.: Evolutionary development and traits in derived Joanusaurids, University of Collinebourg. 1895.

- ↑ d'Everard, Phillipe E.: The Emperor Lizard of Caphiria - Caphirosaurus imperator, University of Collinebourg. 1902.

- ↑ Balboa, Maximus: A comprehensive history of paleontology, pg. 5-9 + 54-59. 2004.

- ↑ d'Everard, Phillipe E.: Caphirian Joanusaurs, University of Collinebourg. 1919.

- ↑ Jour & Leon et al.: Ave Caesar - C. caesar monograph, University of Gabion. 1925.

- ↑ d'Everard, Phillipe E.: Larianasuchops, University of Collinebourg. 1938.

- ↑ Rachet d'Everard was 34 years old at the time.

- ↑ Here is your life - Marshal of Yonderre d'Everard broadcast on Télévision 1 May 2, 1992.

- ↑ d'Everard, Phillipe E.: Origin of the Fittest: Essays in Evolution, University of Collinebourg. 1914.

- ↑ Critique of d'Everard's proposed taxonomy disputes his official total of 243.

- ↑ Balboa, Maximus: A comprehensive history of paleontology, pg. 3-6. 2004.

- ↑ Fürster, Johann: Mammalian derivation of the Permian period, pg. 11-14. 1999.