Almadaria: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary Tag: 2017 source edit |

Early modern history |

||

| Line 125: | Line 125: | ||

Riding the boom in prosperity in the early half of the 1500s, the Kingdom of Septemontes set its sights to Vallos as a whole. Near-modern [[Oustec|Oustecian]] ships loaned in exchange for Septemontes textiles and cattle bolstered the navy of the Kingdom, giving them an edge against what was perceived to be the most logical route for expansion; the Polynesians. The extent of the so-called 'Polynesian Kingdoms' as they were homogenously called, stretched south beyond the territory of the [[Neo-Tainean Empire]] and the Gulf of Natsolea which until that point had been the foremost barrier to invasion, and with the land also came cash crops, more mineral wealth, and labor (which beyond the economic benefit, also lay a reward in converting the heathens). The 'Polynesian Kingdoms' were primarily the Riiti Kingdom in the north, the Poutu Kingdoms in the east, and Whakaparu Kingdom in the southwest; the first came under attack in 1553, starting the [[Polynesian Wars]] (1553-1668). Unlike earlier conquests of Septemontes, the cultural and religious differences led to a drastically different result. The soldiery were not only warriors, but explorers and proponents of Catholicism; conversion and massacre went hand in hand. The Royal Army of Septemontes sent heavily armed raiders that easily overwhelmed their southern neighbors, weakened from lack of trade and the Septemontes advantage of gunpowder and horses, as a vanguard for the settlers, missionaries, and administrators that followed. | Riding the boom in prosperity in the early half of the 1500s, the Kingdom of Septemontes set its sights to Vallos as a whole. Near-modern [[Oustec|Oustecian]] ships loaned in exchange for Septemontes textiles and cattle bolstered the navy of the Kingdom, giving them an edge against what was perceived to be the most logical route for expansion; the Polynesians. The extent of the so-called 'Polynesian Kingdoms' as they were homogenously called, stretched south beyond the territory of the [[Neo-Tainean Empire]] and the Gulf of Natsolea which until that point had been the foremost barrier to invasion, and with the land also came cash crops, more mineral wealth, and labor (which beyond the economic benefit, also lay a reward in converting the heathens). The 'Polynesian Kingdoms' were primarily the Riiti Kingdom in the north, the Poutu Kingdoms in the east, and Whakaparu Kingdom in the southwest; the first came under attack in 1553, starting the [[Polynesian Wars]] (1553-1668). Unlike earlier conquests of Septemontes, the cultural and religious differences led to a drastically different result. The soldiery were not only warriors, but explorers and proponents of Catholicism; conversion and massacre went hand in hand. The Royal Army of Septemontes sent heavily armed raiders that easily overwhelmed their southern neighbors, weakened from lack of trade and the Septemontes advantage of gunpowder and horses, as a vanguard for the settlers, missionaries, and administrators that followed. | ||

The relative success of the Polynesian Wars bolstered the image of the Kingdom of Septemontes, allowing ''Rei'' Asunción Duque II to incorporate the Neo-Tainean Empire under their tutelage and expand their influence over Vallos subcontinent. Meanwhile, many monarchs of the House of Duque chose to look inward. | The relative success of the Polynesian Wars bolstered the image of the Kingdom of Septemontes, allowing ''Rei'' Asunción Duque II to incorporate the Neo-Tainean Empire under their tutelage through the Barrienda Compact of 1588 and expand their influence over Vallos subcontinent. Riding this wave of power and influence, the Reis of Septemontes rapidly involved themselves, mostly in conflicts, in the affairs of Vallos as a whole, ranging from interventions on behalf of the Kingdom of Oustec to participation in the Southern Route, often selling Polynesians conquered during war to depopulate and remove resistance to Septemontes settlement. | ||

Meanwhile, many monarchs of the House of Duque chose to look inward. Against the backdrop of expansionism and prosperity, Catholicism became more of a driving force in Septemontes. In order to bridge the divide between the Tainean and ex-Latin populations, the Catholic Church of Almadaria in full support with the House of Duque sought to embrace the hybrid culture of the two living in Septemontes lands; this new force, compacted around the Church, became ‘cuasliatino’. The Decree of Asunción Duque I of 1538 made Latino-Tainean the language of the royal court and that of the land, though often pidgins between Latin and Tainean languages were used in day-to-day life. Developing in tandem, however, with the cultural programs and movements of Cuasilatino-ism and the ethnic alliance between Tainean and Latin was a more volatile racial supremacist ideology predicating itself on Cuasilatino– in this view, Cuasilatinos were bestowed the right to rule over the stretch of Undecimvirate-controlled Vallos (as there were no direct, ‘pure’ descendents of the Latin invaders), the evidence of this being the success of rapidly-unifying Septemontes over all other groups in Vallos with the rise of the pirate kingdoms. Moreover, the ''Rei'' of Septemontes, by the workings of the court, was not necessarily a privilege afforded to royal heritage but rather on ethnic grounds– hence the usage of common names in their rulers. This worked to further solidify the Kingdom by legitimizing itself not only on religious but racial grounds. | |||

This is not to say that, despite the outgrouping of all others, that the ethnic alliance that fell under the umbrella ‘Cuasilatino’ was by any means on even ground. ''Rei'' Godofredo Velasquez (1619-1649) instituted a system of ''Herasure'', or ‘Fairness’, which is to mean a system of preferentially appointing fair-skinned (typically those that fall more on the ‘Latin’ side of the Cuasilatino spectrum) denizens over their more Tainean counterparts. This policy, eventually turned ''de facto'' law of the land, extended towards even provincial administrators and bureaucrats, reserving most government positions for Latin-passing subjects. This pressed many Taineans, mixed Cuasilatinos, and long-since naturalized Polynesians to the bottom of the social hierarchy that extended from the royal gardens to agricultural settlements. This system of discrimination was especially prominent in the unification of the Neo-Tainean Empire, where many Neotaineans saw their lands seized and their status lower than even the Kingdom of Septemontes’ Taineans. | |||

====Oustec Entanglements==== | ====Oustec Entanglements==== | ||

Arona | The positive relationship between the Kings of Oustec and the Reis of Septemontes was important to both, but it necessarily demanded compromise on both sides. Security on their southern and northern frontiers respectively was a mutual goal; in 1598 the Kingdom of Septemontes lended portions of its Royal Army to the capture and handoff of Arona. Once this was completed, and Septemontes looked beyond its Polynesian borderlands, the tax instituted by Oustec on their foreign policy became their agricultural support for their ally and involvement in their wars. In 1601, the Kingdom of Septemontes entered the long-running Levantine Resistance War (1598-1684), a low-intensity conflict against encroaching Burgundii groups on the side of the Kingdom of Oustec. Meanwhile, | ||

====Barrienda Compact and Unification==== | ====Barrienda Compact and Unification==== | ||

Revision as of 23:27, 21 November 2023

Democratic Republic of Almadaria La República Democrática de Almadaría | |

|---|---|

|

Flag | |

Motto: Un Pueblo Unificado ("A Unified People") | |

Anthem: La Guerra que Luchamos Fuertemente | |

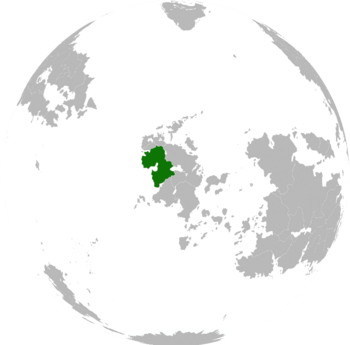

Location of XXX (dark green) In XXX (gray) | |

| Capital and largest city | Piedratórres |

| Official languages | Almadarian Reformed Tainean |

| Ethnic groups | 45.9% Latin or mixed 35% Tainean 16.4% Polynesian 2.7% Other |

| Religion | 64% Catholicism 32.1% Protestant 3.9% Other |

| Demonym(s) | Almadarian (noun) Almadarian (adjective) |

| Government | Unitary Presidential Republic |

• President | Arturo Nuñez |

• Vice President | Graciela Parra |

• Council Governor | Javier Becerra |

| Legislature | National Legislative Council |

| Establishment | |

• Kingdom of Septemontes | 1170s |

• Almadarian Republic | 3 March 1846 |

• Current constitution - Democratic Republic | 14 September 1995 |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,060,263 km2 (409,370 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• Estimate | 48,820,210 |

| GDP (nominal) | estimate |

• Total | $2.023 trillion (2032) |

• Per capita | $41,440 (2032) |

| Gini | 31.6 medium |

| HDI (2024) | very high |

| Currency | Almadarian Valverde (AVA) |

| Driving side | right |

| Internet TLD | .al |

Almadaria, officially the Democratic Republic of Almadaria, is a sovereign country in Vallos, a subcontinent of Sarpedon. It is neighbored by Arona and Vespera to the north, Rumahoki to the east, and Takatta Loa to the south. Its shoreline extends against primarily the Polynesian Sea, though its eastern border includes a shared freshwater body of water with its western neighbor. The Democratic Republic is a megadiverse nation, with one of the highest biodiversity per square kilometer across its rainforest, highland, grassland, and desert zones. The economy of Almadaria has significant government intervention, with most public services resources (water, electricity, transport, telecommunications, healthcare, etc.) being controlled or funded by the government. Nevertheless, private industries, including foreign ones, flourish in established free trade zones which benefit all involved from tax incentives and domestic investment. Almadaria has a high rate of literacy, and an equally high level of higher education attendance; this has contributed to both the growth of the economy as well as the standard of living. The tourism, financial sectors are the two major contributors to Almadaria’s GDP. The government of Almadaria is a semi-presidential, representative democratic republic with a multi-party system. Based on Cartadanian practice, it is broken into three branches (Executive, Legislative, and Judicial), though the legislative exercises significantly more power over the executive, primarily by having no ability to be vetoed by the President and being able to set the government budget.

Almadaria underwent intense political instability in the later twentieth century, its primary cause being decades of political repression under President Sergio Arbelaez. Despite Arbelaez leaving office in 1996 and sweeping political reform thereafter, a low-intensity conflict against fringe guerilla and criminal groups exists to this day.

Almadaria is a member of the League of Nations. Though nominally non-interventionalist, the government does willingly lend its armed forces to the peacekeeping efforts of the organization.

Etymology

Almadaria originates from a loan word from ninth-century Caphirian observers to describe the region of Vallos that had a ‘soul of its own’, possibly referring to its incongruity to the rest of the Undecimvirate’s territories and increased combativeness of the Kings with one another. Other speculation suggests that the divided nature of the land, with indigenous groups and Taineans split on either side of the Undecimvirate’s southern borders, created a interminable friction with the Caphirian-placed Kings. ‘Almadaria’ went on to describe primarily the northern half of the modern-day nation, though centuries of cultural diffusion and political interdependence– though no particular demographic diffusion took place– had roped the southern part under the Almadarian umbrella.

History

Ancient Era

The first accounts of the native inhabitants of Almadaria, the Vallosi, came from southerly-migrating Taineans after 500 BCE which later reported the complete disappearance of those very same Vallosi. It is suspected that the the Cronan-Vallosi hybrid peoples, originating from the north, and the later limited Polynesian advances northward, displaced or assimilated the Vallosi. Little remains of the Vallosi save for genetics and relics of their material culture-- notably shark pottery, which had been particularly advanced in the Gulf of Natosolea, utilizing high-fired ceramics and earthenware with ash glazes as early as 1700 BCE. Particular to Vallosi living in the Marcete Bay area were beads with a unique green glazing made presumably from tree sap.

The primary makeup of political life was small communities, often agricultural, harvesting rice and raíva, a starchy root vegetable. Most evidence of the Vallosi, and later Tainean peoples that merged shows that they were sophisticated fishermen, using nets and large canoes to bring in even deep-sea fish.

As Adonerii Latins swept across the continent from 650 BCE to 100 BCE in their concentrated and infrequent settlements, larger political formations began to emerge. These typically were no larger than the city-states they emulated, but the increased concentration of population was paired with the consolidation and exportation of culture and trade. Routes through the jungles and over the tropical grasslands enabled a flourish of Tainean and Latinized indigenous written languages, and commodities such as rice and textiles flowed in bulk, as well as a burgeoning spice trade.

By the end of the 2nd Century BCE the Cakai Kingdom, heavily inspired by Latin tradition and practice, had organized efficient and ubiquitous trade, becoming an economic heart of antiquity Almadaria. Its reach became so wide that Cakai ships travelled along the eastern coast of Vallos seeking new trade routes and partners.

With the coming millenium, increased instability in other parts of Vallos paired with resentful Tainean-majority polities led to a collapse of the community around the Cakai Kingdom, as its trade dwindled and influence waned.

First Vallosian Warring Period and Tainean Predominance

In the power vacuum left the Cakai Kingdom in 18 BCE, widespread conflict ensued between numerous city-states over the duration of centuries. Though the fighting was typically omnidirectional, there were many instances recorded by the historian Pendongeng of conflicts being fought along clear Tainean-Latin lines, such as the Pont Wars (130-154 CE). A consequence of this period of turmoil was the loss of earlier periods' artistic faculty, with most creative works-- beyond cheaper reproductions of the bona fide-- diminished to funerary works, such as unglazed earthenware pots.

However as the period of intense disorder grew to a close, many of the coastal societies that dwelled on what was once the seat of the Cakai Kingdom were shattered and reeling from the destruction to their lands; droves immigrated to the north and south, looking for stability and prosperity. The former lands of the Cakai Kingdom would never know the same level of prosperity and would remain in obscure villages for the following centuries.

As the region stabilized, it became clear that there was a new power to answer to; that of the Tainean Empire. The Tainean Empire grew from the conflict, at which it fortunately was stationed at the periphery, by having warfighting experience at navigating the dense inland jungles. While this staved off most adversaries, what truly caused the Empire's rise to power was its connections over Lake Remenau, which facilitated trade between other Vallosian polities. A strategy of piggybacking the newborn Lake Remenau slave trade and cunning pragmatism with their neighbors allowed the Tainean Empire to flourish. Traded frequently through the Empire was gold and spices, bringing the Empire into prominence. Even word of the Tainean Empire's prosperity reached the annals of the Caphirian Imperium, from which delegations were later cordially dispatched.

The Tainean Empire also saw social upheaval; the Taineans, traditionally found in subservient roles, found themselves elevated to merchant and administrators. Surprisingly, even with a Tainean-majority government, most records point towards the Tainean Kings having an even hand with its denizens of Latin, and even Polynesian, descent. This attitude, at the end of a bloody period in history, is claimed by many to have shaped the modern world by not splitting Vallos down racial lines.

Caphiric Undecimvirate

Soon, the calls of lesser kingdoms in Vallos became too much to ignore for the Caphirian First Imperium. Despite the relative calm of the region at that point in time, Caphirian Legions overwhelmed the recovering landscape of Vallos. In a series of decisive engagements, even the Tainean Empire was in full retreat, its crown and remainder of its forces fleeing south of the Gulf of Natsolea.

The Undecimvirate was not entirely Caphirian; though tributaries of the Imperium, the eleven kings that ruled over their respective fiefs all over Vallos were given a great degree of latitude over their agendas, so long as the tributes were on time (and as it often was, overloaded). Nevertheless, the Undecimvirate implemented a social order distinct and entirely exclusive to the former powers that reeled in the south, licking their wounds from the Caphirian invasion. While the Caphirian policies and organization revolutionized society in the north just as the Adonerii Latins had, indigenous and Tainean powers were left sidelined or left behind entirely.

Significant infighting, to a degree, became the status quo of the Undecimvirate. Each King, with their own armies and own agenda, fought petty wars to plunder one another. Among the most successful was the Portana Undecimvirate, whose pragmaticism and strategic decision-making helped to keep them always at the top of the tributaries.

Second Warring Period

With the waning of the Second Imperium came increased uncertainty among the Caphiric kings. As the threat of Caphirian intervention to enforce the terms of their agreement subsided, so did the unwritten rule of self-conquest among the Undecimvirate. When the Second Imperium finally collapsed in 1172 CE, Caphirian Vallos was already in a quagmire of internal conflicts, and the death knell of their administrators was the final straw.

With no divinely-inspired armada and legions behind their back, the Kings of the Undecimvirate quickly lost legitimacy, falling into a desperate civil war that mimicked the one happening on mainland Sarpedon. Adding to this was the rump Tainean Empire, in conjunction with other marginalized groups in face of the Undecimvirate, taking advantage of the instability and annihilating any hope of such a united Vallos, taking up around half the land area of the subcontinent, forming ever again.

The Neo-Tainean Empire, formed out of the altered territories and renewed by plundering the classical marble-and-limestone cities of a greater empire than them, quickly took back much of its former territory. With the pressure of Caphirian influence gone, many of the more southerly Polynesian states began to organize, forming prominent Kingdoms to oppose their Tainean-majority neighbor. Tainean kingdoms emerged in the north, too, taking inspiration from indigenous cultures, becoming the Manaqids and Lipipiqs, which persisted for hundreds of years until the end of the 2nd Warring States Period.

Many new kingdoms formed in the ashes of the Undecimvirate, made up of a completely new cultural force than what had existed in their place in 700 CE: the Cuasilatinos, their societies heavily imprinted on their Caphirian forebears.

Those that remained in the image of what had been were exiled and rapidly receding. The Kingdom of the Ossanids (1172-1530), and short-lived Latinic Kingdom attempted to hold onto the Caphirian stability they had once known, but found themselves embroiled on all sides with hostile native Vallsian kingdoms, trained in the same style of warfare as they, and eager to conquer those who had once represented power.

In the meantime, the power imbalance would soon stabilize; in the north, the Kingdom of Septemontes, the east, the Neo-Tainean Empire, and in the south, the increasingly organized and Polynesian kingdoms.

Free Kingdom Era

During this time, it became increasingly apparent that through a series of alliance-building, selective conquest, and upward progress recaptured from the Caphirian Undecimvirate, the Kingdom of Septemontes became a power in what would be northern Almadaria. The Kingdom, made up of Cuasilatinos, largely adopted the structure not of the Undecimvirate but of the Imperium ; an absolute power resting in the monarch while the Christian faith was enshrined as part and parcel of government. With its streamlined hierarchy, efficient government, and ambitious leaders, the Kingdom of Septemontes fostered a period of western Almadarian prosperity with its rebuilding and maintenance of durable limestone aggregate roads and beneficial relations and profitable trade agreements with its neighbors, such as the Principality of Auctodoria of which it was suzerain, or the city-state of Mareterra.

While the Neo-Taineans and the Cuasilatinos maintained an uneasy truce with a buffer zone between them, the Kingdom of Septemontes picked off its adversaries one by one. Beginning with the Manaqid Wars (1353), the Kingdom methodically conquered the Manaqids, culminating in the Battle of La Cancha (1354). The Treaty of Avevalles (1361) further reduced resistance to the gathering power of the Kingdom of Septemontes by promising non-interference to the closed Ossanid Kingdom. The expansionist Latinic Wars (1410-82 CE) reduced the holdover Latinic Kingdom to broken, shattered tribes. By 1400, the Latinic Kingdoms had become further weakend and divided than they were at the start of the century.

In the court of Septemontes, amidst Manaqid insurrections and other trivial matters of state, the King, or Rei, Fernando Olmedo III, inheriting the Kingdom from the nearly-150 year-long line of the Olmedian dynasty, set his eyes across the waters of the Gulf of Natosolea. The former Undecimvirate had already been well-plundered and its rulers established, but those that had escaped the clutches of the Caphirians were considerably weaker, less developed than the Cuasilatino societies that had formed. Rei Olmedo III sent the first surveyors across Vallos to document the south that the north had seemingly left untouched since the days of the Cakai Kingdom. However, his reign was devoted primarily to managing its subjects and muddling through the messy remains of first the Lipipiqs, then the Latinic Kingdoms.

Across Vallos, the absence of the Undecimvirate and its strict, necessarily vicious infighting became internalized. In time, policy and inter-Vallosian violence cultivated by incessant tributary conflict and two Warring Periods was directed both outwards for the first time and further inwards. The formation of Piratocracies essentially represented the first native Vallosian expression of foreign policy; the interception and self-enrichment off of another nation's trade. Meanwhile, as pirate kingdoms formed in the north and south of Vallos up to 1600 at their peak, it had a stifling effect on coastal civilizations across the board. For those left out of the pirate trade, it produced an opposite effect; inter-Vallosian trade through land routes were established, to circumvent the threat of pirate attacks as well as build up inland economies and urban centers, producing more pirate-resilient societies.

During this time, however hostile the interchange was between Vallos, Sarpedon, Levantia, then Crona, Catholicism spread south and became in some places the primary religion overnight. In 1566, Asunción Duque II (Or Asunción the Catholic) baptized themselves a Catholic and pressured subject and ally alike, although Christian, to convert. When the Kingdom of Oustec was founded in 1566 and quickly established itself as one of the foremost northern Vallosian powers, Catholicism found itself as having paved the way for close relations between Oustec and the Kingdom of Septemontes. The two were strange bedfellows, considering the thoroughly illegitimate basis of the Oustec crown, but the maritime power of Oustec I and the manpower and minerals of Septemontes made the two prosper together. The Congress of Lacusentia (1570) formalized relations between the two Kingdoms, and from then on their fates would be roughly linked.

Early Modern

The turn of the 14th century established the Kingdom of Septemontes as a major component of western Almadaria; the turn of the 16th century established it as a major power of Vallos. Bolstered by a close and bordering on parternalistic relationship with the Vagercatores, or Merchant Kingdoms, and itself under the maritime umbrella of the Oustec, the Kingdom of Septemontes traded along the western shores of Vallos, reaching even far enough to access the sophisticated luxury resources of mainland Sarpedon. Silver, limes and spices, and leathers from the burgeoning rancher culture forming in the Astol Plains were loaded onto indigenously-built trade ships, sent across the sea in exchange for luxury textiles, new crops, and ideas readily taken in by the advantage-seeking Kingdom of Septemontes. The dogma of the Kingdom was changed, and with the Catholic Church and increasing sophistication of the monarchy, the newly-coronated House of Duque seemingly embraced the example of the de Welutas. The Kingdom of Septemontes, under Asunción Duque I and Asunción Duque II, underwent reform to streamline royal authority within the Kingdom and amalgamate its constituents, including the Kingdom of Auctodoria, the Vagercatores, and more recent territorial additions.

Riding the boom in prosperity in the early half of the 1500s, the Kingdom of Septemontes set its sights to Vallos as a whole. Near-modern Oustecian ships loaned in exchange for Septemontes textiles and cattle bolstered the navy of the Kingdom, giving them an edge against what was perceived to be the most logical route for expansion; the Polynesians. The extent of the so-called 'Polynesian Kingdoms' as they were homogenously called, stretched south beyond the territory of the Neo-Tainean Empire and the Gulf of Natsolea which until that point had been the foremost barrier to invasion, and with the land also came cash crops, more mineral wealth, and labor (which beyond the economic benefit, also lay a reward in converting the heathens). The 'Polynesian Kingdoms' were primarily the Riiti Kingdom in the north, the Poutu Kingdoms in the east, and Whakaparu Kingdom in the southwest; the first came under attack in 1553, starting the Polynesian Wars (1553-1668). Unlike earlier conquests of Septemontes, the cultural and religious differences led to a drastically different result. The soldiery were not only warriors, but explorers and proponents of Catholicism; conversion and massacre went hand in hand. The Royal Army of Septemontes sent heavily armed raiders that easily overwhelmed their southern neighbors, weakened from lack of trade and the Septemontes advantage of gunpowder and horses, as a vanguard for the settlers, missionaries, and administrators that followed.

The relative success of the Polynesian Wars bolstered the image of the Kingdom of Septemontes, allowing Rei Asunción Duque II to incorporate the Neo-Tainean Empire under their tutelage through the Barrienda Compact of 1588 and expand their influence over Vallos subcontinent. Riding this wave of power and influence, the Reis of Septemontes rapidly involved themselves, mostly in conflicts, in the affairs of Vallos as a whole, ranging from interventions on behalf of the Kingdom of Oustec to participation in the Southern Route, often selling Polynesians conquered during war to depopulate and remove resistance to Septemontes settlement.

Meanwhile, many monarchs of the House of Duque chose to look inward. Against the backdrop of expansionism and prosperity, Catholicism became more of a driving force in Septemontes. In order to bridge the divide between the Tainean and ex-Latin populations, the Catholic Church of Almadaria in full support with the House of Duque sought to embrace the hybrid culture of the two living in Septemontes lands; this new force, compacted around the Church, became ‘cuasliatino’. The Decree of Asunción Duque I of 1538 made Latino-Tainean the language of the royal court and that of the land, though often pidgins between Latin and Tainean languages were used in day-to-day life. Developing in tandem, however, with the cultural programs and movements of Cuasilatino-ism and the ethnic alliance between Tainean and Latin was a more volatile racial supremacist ideology predicating itself on Cuasilatino– in this view, Cuasilatinos were bestowed the right to rule over the stretch of Undecimvirate-controlled Vallos (as there were no direct, ‘pure’ descendents of the Latin invaders), the evidence of this being the success of rapidly-unifying Septemontes over all other groups in Vallos with the rise of the pirate kingdoms. Moreover, the Rei of Septemontes, by the workings of the court, was not necessarily a privilege afforded to royal heritage but rather on ethnic grounds– hence the usage of common names in their rulers. This worked to further solidify the Kingdom by legitimizing itself not only on religious but racial grounds.

This is not to say that, despite the outgrouping of all others, that the ethnic alliance that fell under the umbrella ‘Cuasilatino’ was by any means on even ground. Rei Godofredo Velasquez (1619-1649) instituted a system of Herasure, or ‘Fairness’, which is to mean a system of preferentially appointing fair-skinned (typically those that fall more on the ‘Latin’ side of the Cuasilatino spectrum) denizens over their more Tainean counterparts. This policy, eventually turned de facto law of the land, extended towards even provincial administrators and bureaucrats, reserving most government positions for Latin-passing subjects. This pressed many Taineans, mixed Cuasilatinos, and long-since naturalized Polynesians to the bottom of the social hierarchy that extended from the royal gardens to agricultural settlements. This system of discrimination was especially prominent in the unification of the Neo-Tainean Empire, where many Neotaineans saw their lands seized and their status lower than even the Kingdom of Septemontes’ Taineans.

Oustec Entanglements

The positive relationship between the Kings of Oustec and the Reis of Septemontes was important to both, but it necessarily demanded compromise on both sides. Security on their southern and northern frontiers respectively was a mutual goal; in 1598 the Kingdom of Septemontes lended portions of its Royal Army to the capture and handoff of Arona. Once this was completed, and Septemontes looked beyond its Polynesian borderlands, the tax instituted by Oustec on their foreign policy became their agricultural support for their ally and involvement in their wars. In 1601, the Kingdom of Septemontes entered the long-running Levantine Resistance War (1598-1684), a low-intensity conflict against encroaching Burgundii groups on the side of the Kingdom of Oustec. Meanwhile,

Barrienda Compact and Unification

Meridonial War and Collapse of the House of Duque

New Republic

Modernity

Geography

-

Tropical grasslands of the Astol Plains

-

Western foothills of the Niscamanta mountain range

-

Meridional beach

-

View from the Castila River

-

Shot of Piedratorres from Communa 9

-

Dam #2 in the Remenau River Valley

Almadaria is situated with the Polynesian Sea to its west, and bordered by several freshwater bodies of water, such as Lake Remenau, which is shared between the borders of Almadaria and Rumahoki. Almadaria has land borders with Arona, Vespera, Rumahoki, and Takatta Loa, and shares maritime limits with Arona and Takatta Loa. Defining much of the central and southern topography of the nation is the Niscamanta Range to the east, enclosing the Remenau River Valley, and the milder Chapi Range to the south. The highest point is Cerro Vigorito, at 3,244 meters (10,643 ft) above sea level. The largest lake (entirely within national borders) is Lake Musgo, located in the Meridional region.

The Ministry of Environmental and Resource Concerns of Almadaria classified the nation as having six distinct natural regions: the northern tropical grasslands of the Astol Plains which it shares with Arona, the Golfo which forms itself around the Gulf of Natsolea, the Meridional region with dense tropical forests, the narrow highland Niscamanta region nestled in the east which is shared with Rumahoki, the river delta region, historically contested with the southern Polynesian neighbors, of Capiraso, and the continental interior equivalent of Capiraso in Remenau.

The Astol is the tropical grassland surrounding and encompassed by the northern and southern Astol Rivers, which builds into highlands towards the Niscamanta Range. The Astol, combined with the Golfo, contains more than half of the Almadarian population. The Golfo region is formed around the Gulf of Natosolea, which is headed off by the commercially important Mareterra Strait.

Climate and environment

Almadaria broadly experiences a tropical climate, regardless of the time of year, though geographical nuances allows for a diverse number of range of climate zones. The Niscamanta Range presents a pronounced mountain/alpine climate, while the Golfo, Capiraso, and the Meridional regions are hot, humid tropical rainforests. The forested and riverine Remenau valley is a tropical savanna, receiving less rainfall on average than the rest of the country.

As it is just south of the equator, temperatures remain relatively constant year-round, with average highs of 28 degrees Celsius and average lows of 19 degrees Celsius. Generally, the distinguishing feature of the different natural regions is not the temperature but rainfall.

Colloquially, springtime and autumn do not functionally exist in Almadaria; instead, there is the dry season, verano (summer), and the wet season, called invierno (winter). The amount of rain defines the seasons; these seasons tend to coincide with typhoon season in the Kindred and Tainean Seas. The wet season, spanning from May to December, can see an average precipitation of 340 mm; the dry season can see as few as 6 millimeters. The Golfo and Meridional regions receive the most rainfall on an annual basis.

Government and Politics

The Democratic Republic is a semi-presidential representative democracy, sourcing its constitutional principles and and general framework from the venerable legacy of participatory government of Cartadania. The nation's first constitution, fully ratified in 1847, outlined three branches of government in accordance with the principle of separation of powers, dividing it into executive, legislative, and judicial branches. Following the 1995 Constitutional Plebiscite, reform lessened the power of the executive in its authority to manage clandestine or secretive operations, as well as setting up measures for increased government accountability, including several extragovernmental oversight institutions such as the Office Inspectorate of Almadaria (Oficina Inspectorado de Almadaría).

The government of Almadaria, sometimes styled as 'GRDA' (Alm: Gobierno Republicana Democratica de Almadaría) in informal internal documents, is touted as the first successful indigenous Vallosian democracy, with a strong democratic traditions that persevered in face of international conflict and internal crises. Its multi-party legislature, well-established judicial, and kept-in-check executive branch are at the heart of Almadaria's democratic institutions. Its conversion in 1995 towards more legislative power brings in line with a parliamentary systems

Almadaria is known for its distinct constitutionally-enshrined election process, known as 'rat cage elections' among the population, which pits all candidates against one another in a primary election, regardless of party affiliation, and generally the highest four candidates in votes go on to a secondary election. This nonpartisan election process has kept any one party from gaining superiority over one another, diversifying and increasing representation of otherwise marginalized groups. This practice extends from the national government to local governments, though with some variation.

Though the Democratic Republic currently notionally stands as a stable democracy, the reality is far from utopic. Since the Constitutional Plebiscite of 1995 in which inter-branch relations were altered and new checks on executive power were introduced, the government of Almadaria has suffered a personnel crisis involving persistent low-level corruption and unwillingness on most wings of government to accede to the new watchdog measures. Despite many of the checks and balances now levied against the President, the bureaucratic complexity of their branch of government hinders comprehensive oversight, particularly areas of off-the-book interactions or especially 'grey campaigns'. Grey Campaigns are particularly topical in Almadarian constitutional thought, mainly due to the analysis between their moral or ethical shortcomings (or violations) and their necessity for national security.

Executive

The 1995 Constitution of Almadaria re-establishes the Executive Branch as headed by a popularly elected President, who selects their Vice President and cabinet. As a balance to the judicial branch, the Ministry of Justice (clearly delineated under the executive branch), responsible for areas of national law enforcement and administration of law, is headed by the Attorney General, answers to and represents the First Court of Almadaria in Presidential affairs. The Executive Branch exists in a state of dual legitimacy with the Legislative branch, both having democratic features and the ability to shape policy. The constitutional amendments caused by the 1995 Constitutional Plebiscite shaped this relationship to have the President be more subservient to the National Legislative Council, largely removing the veto power of the President for bills, creating a need for the President to form close relationships with their opposite, the Council Governor, and thereby preventing large divisions in government. Despite this, the President is still solely responsible for forming government, though as previously mentioned, unapproved Cabinet choices or policy decisions would lead to the CLN severely limiting the power of the Executive, reducing the position's powers to stalling actions.

The President of Almadaria, serving as head of state and head of government, is elected by popular vote in a nonpartisan 'rat-cage' election to serve a single five-term term, a precedent established in the so-called 'stripping down' of the executive. At the regional level, executive power is vested in Provincial Governors (Almadarian: prefecto), then municipal alcaldes (mayors).

The Cabinet of Almadaria is made up of nine ministries, whose heads are selected, without Legislative veto, by the President. The Ministries and their senior official serve not only as administrators of their respective national focuses, but in an advisory role to the President and Vice President in implementing policy. Subject to frequent government restructuring, the members of the Cabinet as of 2032 are: the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Trade, the Ministry of Environmental and Resource Concerns, the Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of Science and Technology, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, the Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of Education, and the Ministry of the Interior.

Legislative

The National Legislative Council is the sole national legislative body of Almadaria. As a unicameral entity, the National Legislative Council (CLN) consists of a frequently-held, XXX-seat convocation. The seats on the CLN are elected democratically from provincial districts every two years. Ideally a proportional representative system, the party makeup of the CLN is directly related to the winnings of those parties in provincial elections (as there are no legislative bodies in Departments); even against one another. For better or for worse, this 'rat-cage' electoral process prevents urban population buildup from overwhelming the legislature due to forced party infighting to make the first four candidates 'past-the-post'-- this also makes it more practical for elected parties to form ever-shifting coalitions in order to form government. Departments, having no organic legislature, source legal authority from the National Legislative Council while having vested executive power from the President.

The National Legislative Council is presided over by the Council Governor, voted into power by the unicameral body, in order to oversee the institution and the management of its numerous parasite agencies. In order to be eligible for Council Governor, one must have already been elected into the CLN. There are no term lengths. The Council Governor is held responsible by the larger legislature, ensuring flexible and responsive representation of the will of the chamber. The Council Governor is able to control the agenda of legislation, which is voted upon in assembly and then referred to the Executive to pass the bill. Prior to 1995, a 60% bill approval rate in the CLN was needed in order to override a presidential veto; now, the .

The large body of the National Legislative Council is only summoned in its entirety for major policy proposals; otherwise, it is not uncommon for handfuls of councilmen/women to meet in committees, smaller semi-permanent organizations to research and develop policy. Most of these committees are impermanent, although there are committees, named Popular Agencies, which are long-standing; many of these exist as oversight bodies and liaisons to their executive Ministry counterpart, though other concern standing issues, including ones such as anticorruption, intelligence oversight, and constitutional debate.

Judicial

The Judicial branch is made up of institutions present at every level of government-- at the national level, it is represented by the First Court of Almadaria. The First Court is headed by four high courts: consisting of the Civil High Court, for penal and civil matters; the Constitutional High Court, which weighs policy produced by the CLN against the principles of the Almadarian Constitution and established precedent thereof; the State High Court, which in turn manages the executive branch by establishing administrative law; and finally, the Auditor's Court, which is a self-regulating agency of the First Court.

Members of the the First Court of Almadaria are selected by the National Legislative Council and approved by the President. These judges serve terms no longer than twenty years.

Federal subdivisions

At the national level, Almadaria is divided into twelve Departments and one capital district, separate from the municipality it forms. The departments are divided into provinces, ran by prefects (Almadarian: prefectos). These are further divided into subnational entities of municipal districts, or municipalities. The Pardos Act of 1997 reformed the system in the cases of low-population municipalities to fit together in larger municipal systems in order to better distribute funds, leading to the derisive call, "Uno freno, doce caballos" (one bit, twelve horses).

Each of the levels has a local government with a governor (in provinces, prefects; municipalities, alcaldes), though deprived of legislative bodies. At sub-national levels, most positions are directly elected, unlike the President's Cabinet.

Politics

The voting age in Almadaria is set at 18, having traditionally been set at 25 until the mid-twentieth century. The existence of a unitary legislature simplifies and galvanizes voter participation around singular elections and candidates, where party politics largely come into play. The National Legislative Council is divided at any one time, necessitating the creation of coalitions to win a majority of the legislature, decisively choose a candidate for Council Governor with which to introduce and pass policy. The 1995 Constitutional Plebiscite revolutionized the political landscape of Almadaria, breaking the deadlock between the emplaced and traditionally conservative Valverdian Popular Front and the shackled and traditional opposition party of the Almadarian National Union. The changing of the electoral process signaled an end to the VPF domination of government and thrust the legislature into a multi-party democratic system. Forming into coalitions with similar-policy parties (such as the center-right Democratic Liberties Alliance) not only ensures smaller or similar parties a higher chance to win government office, but also serves to exclude extremes (such as the right-wing Liberal Party or the left-wing Civic National Party) from controlling significant portions of government.

The current state of affairs of the legislature shows the major poles of power; that being the big-tent left-wing Almadarian National Union facing off between the variable makeup of the Democratic Liberties Alliance coalition, optionally including the minority issues-focused Justice and Development party and swing Congress of Freedom party depending on policy focuses. With the founding of the Liberal Party in 1982 under the right-wing government and the increasingly extremist views enshrined by the party platform, it has created a debate in constitutional and legislative circles whether the government has the ability to ban political parties (even if members of that party have won local, and even Presidential office).

Foreign Affairs

Military

Established by the Constitution of Almadaria, the basis of national defense is embodied by the Armed Forces of Almadaria (FAA). Tracing its lineage from the twentieth-century Republican Army and the Royal Army of Septemontes, the Armed Forces of Almadaria comprises of the Almadarian Land Forces, the Navy, and the Air Forces as its main components. Control of the FAA lies under the jurisdiction of the President and the Ministry of Defense, though as an institution it is obliged to defend and protect the Constitution.

Demographics

What kind of people live in your country? Bad ones

Ethnicity

Self-reported ethnic origin in the XXX (20XX)

What ethnic groups make up your country?

Language

What language or languages do your country's people use? Are there any previously used languages no longer common? Are these languages native to your country or shared with another?

Religion

What do your country's people believe in religiously, if anything? How many groups are there?

Education

How many people in your country are educated?

Culture and Society

What do your people do, and what are they like?

Education

What is your country's education system like? How do the schools work? What do people think about education?

Attitudes and worldview

How do your country's people view life?

Kinship and family

How are families or kinship groups structured in your country?

Cuisine

What do your people eat?

Religion

What do your people believe? Rather than demographics, as above, think about how important religion is to your people and their view about their own and other religions. What is the relationship between the prevailing view and minority religious groups? Is it an official religion, and do any laws exist about free worship?

Arts and Literature

What type of art do your people make? Do they have a tradition of painted art, well-crafted television shows, or great music?

Sports

Does your country have any major sports leagues? What types of sports are played, both professionally and for fun by your country's people?"

Symbols

Are there any prominent symbols which are well known to represent your country?

Economy

Almadaria has an emerging, upper middle-income mixed-market economy, ranked as the 17th largest economy, or 19th largest by GDPPC. The Almadarian economy is highly developed, with an equally as high standard of living. This is helped in part by policy-minded government intervention by the Ministries of Trade and Ministry of Environmental and Resource Concerns. As well, due to the government's policy of courting foreign investment, the Almadarian currency sports a high PPP; since late 20th century, the Almadarian Valverde has been a competitive currency on the foreign exchange, hovering near or around the value of a Levantine Taler. Foreign investment is partly incentivized and partly kept under control through the International Trade Interest Regime (ITIR/RICI); this policy establishes laissez-faire geographic zones for foreign companies to operate, with the added benefits of exemption from value-added taxes, among others. This makes it possible for domestic businesses to operate without strangulation from their foreign competition. Almadaria scores well on the Human Development Index, is known for its inventive and internationally competitive financial services and banking, which operate in cooperation with both the Almadarian government as well as having influences in the Vallosian Economic Association.

A proponent of economic liberalism from its foundation, Almadaria has formed a cornerstone and historical anchor of the economic heart of Vallos when its primary peers suffered from instability. Almadaria's (formerly the Kingdom of Septemontes) lasting economic centrality to Vallos and sweeping development occurred in the 18th and 19th centuries as a result of the country's role in the Southern Route, the cause of many historical controversies. In the modern era, Almadaria has been a founding member of the Vallosian Economic Association (VEA), as well as signatories to PROSPER Program and other international initiatives.

A major controversy in the calculation of economic wellness of Almadaria is the inclusion of the Department of Capiraso, a political department located in the larger Carrediaz/Karetia'asu region. This region has historically experienced significant political and criminal turmoil and additionally a low-intensity conflict since the mid-2020's, largely in the wake of the start of the Akanatoa War. This instability, despite the intervention of state forces, has significantly degraded the economic well-being of the area compared to the rest of Almadaria. Many voices in legislature have called for its exclusion from official statistics, and even censuses -- others have called for its exclusion from the nation as a whole.

Employment, Growth Rate, and Inflation

The LFPR (labor force participation rate) since 2010 for Almadaria has hovered around 83.2%, or a labor pool of approximately 40,600,000, largely in part due to early employment (the average Almadarian typically acquires a job around age 16) and an abundant minimal-labor job market which suits itself for longer life and later retirement. Since the economic recovery from the 2018 recession, unemployment has maintained consistent around 11%, contributed to by expansive government-funded social networks, including healthcare. Inflation has historically been a problem of the Almadarian economy, afflicting the nation periodically in the 20th Century, but increased financialization and government regulation have minimized the variation in value of the Valverde, limiting inflation by 3.55% every year. Growth in the public sector of the economy typically trails behind the normally-successful private sector, due to government focus and investment being prioritized there.

A very small fraction of the Almadarian labor force works in the primary (agriculture, resource extraction) sector, due to increased mechanization paired with increased reliance on imports; as of 2030, only 7.4%. A larger proportion (27.1%) serves in the secondary (manufacturing) sector, while the majority (65.5%) works in the tertiary sector, reflective of the developed Almadarian service economy. Moreover, despite the large proportion of the labor force in the primary and secondary sectors of the economy, more than 87% of the GDP comes from the tertiary sector.

Industries and Sectors

The services sector of the Almadarian economy is its strongest, led first and foremost by its financial services industry, as well as the telecommunications industry and information technology industry, followed closely by a mature retail industry and real estate market. Initially agricultural, Almadaria experienced a brief period of industrialization before rapidly financializing in the later period of the 20th Century. The core of the sudden shift towards financialization lies in the early origins of the Almadarian banking system in the Vagercatores, or the Merchant Kingdoms, that emerged after the fall of the Caphirian Undecimvirate, with the first bank in Almadaria founded in Interumina in 1549. After the Second Great War, the Edmundo Virgen Administration (1948-58) led the charge towards increased financialization of the economy in an attempt to sidestep increasing agricultural and mineral preponderance of Almadaria's neighbors and the developed and first-class manufacturing economies of the Burgoignac Equatorial Ostiecia. This way, necessary political and societal reforms that made up President Virgen's administrative platform could be funded without being dependent on mineral, energy, or up-till-then uncompetitive industries. It was during this time the CLN passed several banking secrecy laws in the 1950's, which began to attract futures contracts for the real mineral resources of Almadaria. The increased investment was then used to double down on financial infrastructure, beginning the so-called cycle of a 'runaway' financial economy while the government used the dividends for small, sophisticated projects.

Agriculture and Fishing

Mining

Energy

Manufacturing

Construction

Financial Services

The financial services economy collects the lion's share of domestic and foreign investment, growth, and policy focus. There are more than 411 distinct financial firms and cooperatives in Almadaria, from which come seven of the ten richest Almadarian citizens. The financial services come primarily in the form of banking in its commercial and investment forms, as well as financial exports, insurance, foreign exchange brokerage, as well as advising and analysis. Grupo Caballero, an Almadarian firm worth 34.6 billion USD, provides accounting services to international organizations such as the Vallosian Economic Association.

Telecommunications

Information Technology

Retail

Real Estate

Education

Research and Development

Public Sector

Transportation, public health and healthcare