Arunid Empire

The Arunid Empire was a powerful Fravarti-Zoroastrian empire in the Daria region of Audonia during Classical Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages(~372BC-884 CE), following the collapse of the Umaronid Empire of Daria in 738CE and the Banner Wars. It dominated the trade networks of the Aab-e-Farus and its provinces stretched from modern day Kandara all the way to northern Battganuur. The state's founding background as part of a zealous religious movement led by the communitarian 4th Century prophet Fravarti led to later disastrous campaigns by its founding Padishah Aadesh The Conqueror to expropriate the lands of the Erezu class and to liquidate the Barsom Armies and directly centralize administration around the Crown. These campaigns, continuing under his successors, led to marked decline of Darian civilization, and its conquest by the Oduniyyad Caliphate after scarcely more than a century of existence.

Arunid Empire Demāna Arun | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 372 BC–884 CE | |||||||||

|

Flag | |||||||||

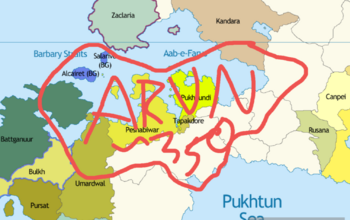

The maximum extent of the Arunid Empire in ~350 CE | |||||||||

| Capital | Sayendag | ||||||||

| Religion | Zoroastrian, Hindi, Mazdak, Manichean | ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Aruni | ||||||||

| Government | Empire | ||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||

| Historical era | Classical antiquity | ||||||||

• Established | 372 BC | ||||||||

• Capture and destruction of the Citadel of Sayendag by the Oduniyyad Caliphate | 884 CE | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

| |||||||||

Its origin, wartime capital, and powerbase was in what is now Pukhgundi, where the vestiges of its legacy can still be most obviously seen. While it was a very cosmopolitan empire made up of thousands of ethnic groups, religions, and languages, the ruling clans were from the Bisht region from modern Pukhgundi.

History

The power base of the Arunid Empire was formed during the anarchic period following the collapse of the Umaronid Empire when the control of the Erezu class's 6th-8th century nominal control over the regional Banner Armies under the Zardari dynasty disintegrated, Arun, leader of the Tripathee clan and commander of the Pukhgandi Barsom (Avestan for "Collection", "Bundle"), quickly established control over the Pukhto Barsom after his father-in-law died and he pressed his claim to headship of his wife's clan in 372 BCE. The pseudo-Kingdom carved out by the combined banner armies of Arun quickly became a powerhouse in the region and Arun's son.

The Arunid dynasty was ruthless and shrewd. Fathers and mothers teaching the art of cunning and guile to their children, punishing sloth and greed to ensure that ambition was a key factor of every new generation. There were 500 years of continuous expansion both through military conquest and through trade and diplomacy. They were to Daria what Cao was to Dolong. In fact, these empires were strong trading partners and military allies against the Huns of northern Dolong.

One of the most revered rulers in Arunid history was Emperor Ashoka, who ascended to the throne in 268 BCE. Known for his conversion to Buddhism after witnessing the horrors of war, Ashoka pursued a policy of non-violence and religious tolerance. His reign marked a golden age for the empire, with the spread of Buddhism throughout the region and the construction of the famous Ashoka Pillars. The Arunid Empire experienced a period of cultural flourishing during this era. Its cosmopolitan cities, such as Peshawar and Taxila, became centers of learning and trade, attracting scholars and merchants from across the known world. Art, literature, and philosophy thrived, with the synthesis of Pukhti, Persian, and Istroyan influences.

In 324 CE, Aadesh (later known as The Conqueror) courted the Zoroastrian scholar and mystic Fravarti, who espoused a radical revision of traditional Darian Zoroastrian doctrine. According to Fravarti, God had originally placed the means of subsistence on earth so that people should divide them among themselves equally, but the strong had coerced the weak, seeking domination and causing the contemporary inequality. This in turn empowered the "Five Demons" that turned men from Righteousness—these were Envy, Wrath, Vengeance, Need and Greed. To prevail over these evils, justice had to be restored and everybody should share excess possessions with his fellow men. Aadesh, shrewd as he was, realigned Fravarti's teachings towards his own aims, reimagining his communitarian vision as a statist one, and using the influence of loyal clergy, he established Fravartism as a doctrine of Rigid Centralization of State, Religious, and Social bodies around the person of Aadesh, who was given a special theological role akin to the role of the Imperator-Pope in later Caphirian Catholicism. The religious fervor caused by the spread of Fravartism across Daria led to the heightening of civil strife in the region, with legions of fanatics often fighting alongside Aadesh in his campaigns against the other 10 remaining Barsom Armies.

With each new confrontation with the Barsom Armies, he was ruthless in their total liquidation, with mass executions of their clan leaders being commonplace. A notable exception to this rule, which later would prove to be key to the Arunid Empire's downfall, was Aadesh's sole defeat at the battle of Qandagozar at the hands of Ardafravash of the Khadem Clan, leader of the Adunishan Banner Army, who, after his retreat into the deserts of the interior would be the progenitor of the ruling family of the Oduniyyad Caliphate.

As the 7th century dawned, the Arunid Empire faced growing external pressures. The emergence of the Oduniyyad Caliphate brought a new force into the region, driven by religious zeal and military might. Caliphal forces began encroaching on Arunid territories, sparking a series of conflicts that would culminate in a decisive battle in 884 CE. The Battle of Neshapur in 884 CE marked the end of the Arunid Empire. Caliphal forces, led by General Al-Abbas, proved too formidable, and the Arunid capital fell. The empire was dissolved, and its territories were gradually absorbed into the expanding Oduniyyad Caliphate.

Government

The Arunid Empire was characterized by a strong centralized monarchy, provincial administration also dominated by a professional, court-educated bureaucracy, and a legal framework that promoted religious tolerance and social welfare. The empire's rulers, as preached by their Fravarti religion, played a significant role in fostering a rich cultural heritage and supporting the well-being of their subjects.

At its core, the Arunid Empire was a monarchy, with an emperor (King of Great Kings) at its head. The empire was led throughout its history by members of the Arunid Dynasty. The emperor held absolute authority over the empire, making key decisions related to governance, military, and foreign affairs. The line of succession was typically primogeniture, passing from father to son, although there were exceptions, occasional power struggles, and a few instances of non-familial regencies. The empire was divided into provinces and kingdoms, each governed by a king, and prince, governor, or viceroy appointed by the emperor. These provincial rulers were responsible for maintaining law and order, collecting taxes, and implementing imperial policies within their territories. Local customs and traditions were often respected to some extent, allowing for a degree of cultural autonomy within the provinces. To assist in the administration of the vast empire, a bureaucratic system was developed. This bureaucracy included professionals who managed various aspects of governance, such as taxation, justice, and public works. Prominent bureaucrats often served as advisers to the emperor and played key roles in policy formulation. The empire had a well-developed legal system with codified laws and regulations. Emperor Ashoka, in particular, is known for his edicts, which were inscribed on stone pillars and rock surfaces throughout the empire. These edicts promoted principles of justice, morality, and religious tolerance, and they provided a legal framework for the governance of the empire in its last days.

Economy

The economy of the Arunid Empire was a complex and evolving system that developed over the course of its 1300-year history. It encompassed a vast and well connected network of sectors spanning the whole of Daria, the Aab-e-Farus, and at its peak some of the sea lanes in the Sea of Istroya. The Empire witnessed significant technological transformations, reflecting the empire's priority on investing in great thinkers from all across the known world. Because the Empire was strategically located at the crossroads of important trade routes, it facilitated, and taxed, the exchange of goods and ideas between the East and West. The empire's cities, such as Peshawar, Taxila, and Multan, emerged as major trade hubs, connecting merchants from as far as Coa and Great Levantia. Valuable commodities like spices, textiles, gemstones, and precious metals were traded, contributing to the empire's wealth, but it was the taxation of the movement of these goods on Arunid roads and ships that made the Empire rich beyond measure.

Agriculture formed the backbone of the Arunid economy. The fertile lands of the Darian coastal plains and mountain sides and the agricultural innovations of the time allowed for the cultivation of a wide variety of crops, including rice, wheat, barley, and various fruits and vegetables. The Empires investment in extensive irrigation systems, such as canals and wells, played a crucial role in boosting agricultural productivity throughout all of its provinces. The surplus food production supported both a growing urban population, thinkers, craftsmen, manufactories, and trade.

Artisans and craftsmen played a pivotal role in the Arunid economy. Skilled workers produced high-quality textiles, ceramics, metalwork, and jewelry, which were in demand not only within the empire but also in international trade. Craftsmanship reached impressive heights, as seen in the intricate construction and decoration of grand temples and palaces. In levels not seen in many other ancient civilizations these manufactories were maintained as part of a uniquely complex but regular economic network. These required a steady supply of consistent materials to be supplied to them and there is strong evidence that villages and towns were built around maintaining supply lines to various points throughout the empire to ensure this happened.

Taxes were collected in the form of agricultural produce, land revenue, and trade tariffs, the most lucrative form of taxation. The revenue collected was used to maintain the empire's infrastructure, support the military, and fund ambitious works projects. Emperor Ashoka, in particular, is renowned for his emphasis on social welfare and public projects, such as the construction of roads, hospitals, irrigation works in semi-arid zones, and education centers. Ashoka was also the first to bring in scholars from the Ancient Istroyan civilization to join him at court. This became en vogue for provincial kings and princes to also have minor Istroyan scholars and philosopher on their advisory councils.

Over time, the Empire faced various economic challenges. External pressures, including invasions and the expansion of the Oduniyyad Caliphate, disrupted trade routes and contributed to economic decline. Inefficient governance and overexpansion also strained the empire's resources. Despite its economic achievements, these factors ultimately weakened the empire's economic foundations.

See also