Battganuur

Republic of Battganuur | |

|---|---|

|

Flag | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Alihijan |

| Official languages Recognised minority languages | Umardi, Burgoignesc |

| Demonym(s) | Battganuuri |

| Government | |

• Chief of Ministers | Faisal-Jallal Asayesh Aslani |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,525,943.29 km2 (589,170.00 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2025 estimate | 204,504,300 |

• Density | 134.018/km2 (347.1/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal) | 3,748,972,827,600 estimate |

• Per capita | 18,332 |

| Time zone | UTC- |

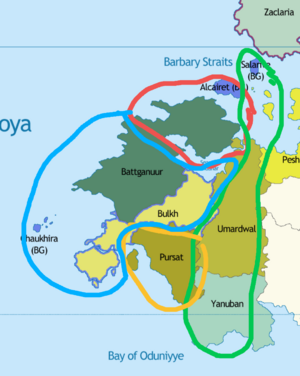

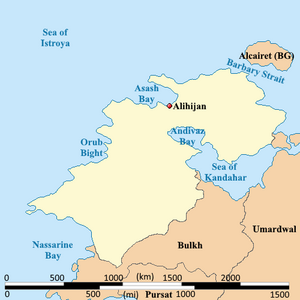

Battganuur is an industrialized and modern nation in western Audonia, stratling the coasts of the eastern Sea of Istroya, the southern coast of the Barbary Strait, the western coast of the Sea of Kandahar, with a small land boarder with Umardwal in the north east, and a long southeastern border with Bulkh. Its coastal areas are heavily urbanized with its interior being largely rural.

Battganuur has a bicameral legislature, a supreme court, and an executive, the Chief of Ministers who acts in the same capacity as a president.

It is a member of the League of Nations, the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, and many other international organizations.

It is a market economy focused on exports, under the watchful eye of Burgundie whose companies have a massive stake in the country's economic activity. It specializes in the assembly of microprocessors and cellphones, as well as the cultivation of tropical hard woods, fishing, and rubber, which also constitutes its major exports. It is an active leader in the Middle seas region's economic activity.

Many scholars have criticized its economic governance and politics, arguing that it is merely a client of the Burgoignesc thalattocracy's economic and cultural might.

The people of Battganuur are predominantly culturally Persian, speak Umardi, and most practice Shia Islam.

Geography

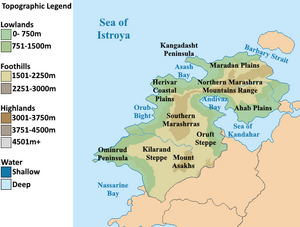

The Marashrra Mountain Range dominates Battganuur's central landscape, running north-south and dividing the country into eastern and western halves. This imposing range reaches elevations of over 4500 meters in Mount Asakhs, its highest peak. The mountains serve as a natural barrier, influencing weather patterns and creating distinct microclimates. The slopes of the Marashrras are forested, providing valuable timber resources and serving as a refuge for diverse flora and fauna. To the east of the Marashrra Mountains lie the fertile plains of Ahab and Maradan. These vast expanses of flatland, watered by numerous rivers and streams, are the agricultural heartland of Battganuur. The rich alluvial soils and abundant water resources support the cultivation of rice, the nation's staple crop, as well as other agricultural products. Battganuur boasts a long and diverse coastline, stretching along the Sea of Istroya to the west, the Barbary Strait to the north, and the Sea of Kandahar to the east. The coastline is dotted with numerous bays, inlets, and peninsulas, providing natural harbors and access to marine resources. The Kangadasht Peninsula, jutting out into the Sea of Istroya, is a region of rugged beauty, with steep cliffs, secluded beaches, and picturesque fishing villages. The Herivar Coastal Plains, bordering the Sea of Istroya, are a fertile region known for its agricultural productivity and tourism potential. The Oruft Steppe, bordering the Sea of Kandahar, is a vast expanse of arid grasslands, used for grazing livestock and supporting a unique ecosystem adapted to the harsh environment. The Oruft Steppe and the Kilarand Steppe, located in the southeastern part of the country, are characterized by arid grasslands and semi-desert conditions. These regions receive limited rainfall and are prone to drought. However, they support a unique ecosystem adapted to the harsh environment, including hardy grasses, shrubs, and various species of wildlife. Battganuur is blessed with numerous rivers and streams, originating in the Marashrra Mountains and flowing towards the seas. These rivers provide water for irrigation, transportation, and hydroelectric power generation. The Aab-e-Farus, the largest river in the region, flows along Battganuur's northern border, forming a natural boundary with Umardwal. Battganuur's diverse geography has shaped its history, culture, and economy in profound ways. The mountains have served as natural barriers, protecting the country from invasions and influencing weather patterns. The fertile plains have supported a thriving agricultural sector, while the coastlines have provided access to marine resources and facilitated trade and cultural exchange. The arid steppes, though challenging environments, have supported nomadic pastoralism and unique ecosystems. The rivers and water resources have been crucial for irrigation, transportation, and energy production. This geographic diversity has also created distinct regional identities, with each region possessing its own unique cultural traditions, economic activities, and social structures. The mountainous north, with its rugged terrain and isolated communities, has developed a culture of resilience and self-reliance. The fertile plains, with their agricultural abundance, have fostered a more settled and community-oriented way of life. The coastal regions, exposed to external influences, have developed a more cosmopolitan outlook.

Climate and environment

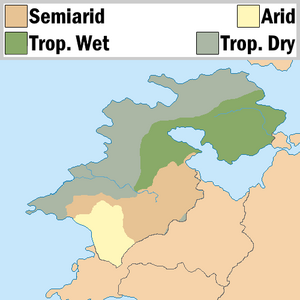

The tradewinds bring moisture from the Aab-e-Farus and the Sea of Kandahar to the northern interior of Battganuur. In the nation's coast picks up residual moisture from the Sea of Istroya but the tradewinds keep it from having a sever rainy season. The southern third of the country, predominantly Nahaqqez State, is dominated by the Great Kavir. The prevailing winds pushing moisture off of the Sea of Kandahar keeps the northern portion of the southern third semi-arid.

History

Prehistory

Battganuur was originally settled by Indo-Aryan peoples who likewise settled areas from Zaclaria to Pukhgundi. These people shared languages with common roots, the Indo-Aryan languages which later diverged into Proto-Umardonian (west of the Sindhus River) and proto-Sindhus (east of the Sindhus River).

Umaronid Empire

The Umaronid Empire, a Bronze Age civilization that thrived in western Audonia from approximately 3300 to 1300 BCE. Renowned for their meticulous urban planning, the Umaronids constructed sprawling cities like Harappa and Mohenjo-daro, characterized by grid-like layouts, multi-story houses, and sophisticated drainage and water supply systems. This meticulous attention to detail extended to their economic practices, evident in their standardized weights and measures that facilitated trade and commerce across the empire. The Umaronids demonstrated exceptional craftsmanship and technological ingenuity. Their mastery of metallurgy is evident in the production of bronze tools and weapons, while their artistry is showcased in intricate seals, pottery, and figurines. Notably, the empire developed a unique script, yet to be deciphered, which tantalizingly hints at a complex language and potentially rich literary traditions. Despite its advancements, the Umaronid Empire eventually declined. While the precise reasons remain unclear, factors such as climate change, shifting river courses, and migrations likely played a role. Nevertheless, the legacy of the Umaronids endures, providing valuable insights into the social, economic, and cultural dynamics of early Audonian civilizations. The empire's contributions to urban planning, metallurgy, and artistic expression continue to inspire and inform contemporary understanding of the region's history.

Classical Antiquity

Northern Battganuur, under the dominion of the Arunid Empire, experienced a profound agricultural revolution, the burgeoning of a lucrative timber industry, and a dynamic cultural exchange that left an enduring legacy on the region's identity. Meanwhile, southern Battganuur, witnessed the rise and fall of empires, the fusion of Istroyan and Persian cultures, and the establishment of a vibrant Christian realm, the Ashrafinid Empire. While the coastal regions flourished under Istroyan influence, the interior of southern Battganuur remained a realm of tribal societies. These tribes, such as the Parthians and the Elamites, maintained their traditional nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyles, herding livestock, cultivating crops, and engaging in trade with neighboring regions. The decentralized nature of tribal power structures made it difficult for a single dominant entity to emerge. Instead, the interior was characterized by a patchwork of alliances, rivalries, and shifting power dynamics. This political fragmentation, while fostering a degree of autonomy for individual tribes, also made the region vulnerable to external incursions and conquest.

Kingdom of Eshel

The Kingdom of Eshel was a Jewish ethnoreligious state formed round 500 BC under King Adud I on the Ominrud Peninsula. It was a regional powerhouse in the eastern Sea of Istroya during the late Classical Period with a strong trade network with the Ancient Istroyan civilization. It remained staunchly independent despite many attempts to subjugate them by the Ashrafinid Empire to the north. It is notable that Eshel fought on the side of the Christians in the Crusades in Audonia from 1167–1428. In fact, the end of the Crusades was a contributing factor to the decimation of the Kingdom by the Oduniyyad Caliphate in 1486.

Arunid Empire

The Arunid Empire's dominion over northern Battganuur, encompassing the present-day provinces of Ahabijan, Andivaz, Takand, Maradan, and Malarand, represents a pivotal epoch in the region's history. The empire's vast reach and influence brought about profound transformations, leaving an enduring legacy that continues to shape Battganuur's identity and development. The Arunid Empire, recognizing the fertile potential of northern Battganuur's plains, initiated a comprehensive agricultural development program. Extensive irrigation systems, including canals and reservoirs, were constructed to harness the waters of the Aab-e-Farus and its tributaries. This led to a significant increase in rice cultivation, transforming the region into a breadbasket for the empire. The surplus rice production not only sustained the empire's burgeoning population but also became a valuable commodity in regional trade networks. Alongside rice, the cultivation of other crops such as wheat, barley, fruits, and vegetables was also promoted, ensuring a diverse and resilient agricultural base. This agricultural revolution not only boosted the region's economic prosperity but also fostered social stability by ensuring food security. Northern Battganuur's lush forests, teeming with valuable hardwoods like teak, mahogany, ebony, rosewood, and padauk, attracted the attention of the Arunid Empire. Recognizing the potential of this resource, the empire established logging operations and implemented sustainable forestry practices. These woods were highly prized for their durability, beauty, and versatility, and were used in the construction of grand palaces, temples, and ships. The timber trade became a lucrative source of revenue for the empire, contributing to its economic power and influence. The demand for Battganuuri hardwoods spurred the development of infrastructure, including roads and ports, further integrating the region into the empire's vast economic network.

The Arunid Empire's dominion over northern Battganuur was not solely an economic endeavor. It also entailed a significant cultural and spiritual exchange. The Fravarti-Zoroastrian faith, with its emphasis on righteousness, social justice, and communal harmony, found fertile ground in the region. While it did not completely supplant existing religious practices, it gained a significant following and left a lasting imprint on the region's spiritual landscape. The empire's cosmopolitan cities, renowned centers of learning and commerce, attracted scholars, artisans, and merchants from across the known world. This influx of diverse cultures led to a vibrant cultural fusion, with elements of Persian, Indian, and Istroyan traditions intermingling with local customs. The adoption of the Umardi language, the lingua franca of the empire, facilitated communication and trade, further cementing the region's integration into the Arunid realm.

Istroyan city states

Beginning in the 6th century BCE, Istroyan mariners, hailing from the bustling city-states of northeastern Sarpedon, embarked on exploratory voyages across the Sea of Istroya. Drawn by tales of fertile lands, exotic spices, and lucrative trade opportunities, they established a series of colonies along the southern coast of Battganuur. These colonies, such as Alexandropolis (modern-day Bandar Abbas) and Seleucia ad Mare (modern-day Bushehr), quickly grew into thriving centers of commerce, culture, and learning. The Istroyans brought with them their language, philosophy, art, and architectural traditions, which deeply influenced the local Persi populations. Over time, a unique fusion of Istroyan and Persian cultures emerged, evident in the syncretic religious practices, the adoption of Istroyan architectural styles, and the widespread use of the Istroyan language in trade and administration. This cultural exchange left an enduring legacy, shaping the distinct identity of southern Battganuur for centuries to come.

Ashrafinid Empire

Audonian Christianity Ruled most of Battganuur and the Alcairet. The dawn of Christianity in the 1st century CE brought about a significant shift in the religious and political landscape of southern Battganuur. The new faith, with its message of salvation and universal brotherhood, resonated with many in the region, particularly among the urban populations who had already been exposed to Istroyan ideas and philosophies. In the 4th century CE, a charismatic leader named Ashrafi rose to prominence. He united the disparate Christian communities of southern Battganuur under his banner, establishing the Ashrafinid Empire. This empire, with its capital at Ctesiphon (modern-day Salman Pak), quickly expanded its influence, encompassing the entire southern region and even challenging the Arunid Empire for control of the Sea of Kandahar. The Ashrafinid Empire was a period of cultural flowering and economic prosperity. Ctesiphon became a center of Christian learning and scholarship, attracting theologians, philosophers, and artists from across the Audonian world. The empire's economy thrived on trade, agriculture, and the production of luxury goods, such as textiles, spices, and precious metals. The rise of the Oduniyyad Caliphate in the 7th century CE marked a turning point in the history of southern Battganuur. The Caliphate's expansionist policies brought it into conflict with the Ashrafinid Empire, leading to a series of bloody wars. In 762 CE, after a prolonged siege, Ctesiphon fell to the Oduniyyad forces, marking the end of the Ashrafinid Empire. The region was incorporated into the Caliphate, and Islam gradually replaced Christianity as the dominant religion. Many of the Ashrafinid aristocracy, refusing to renounce their faith, fled to Levantia, where they established the kingdom of Hištanšahr, preserving their cultural and religious heritage.

Medieval period

The Oduniyyad Caliphate's six centuries of rule left an indelible mark on Battganuur. The spread of Islam transformed the region's religious and cultural landscape, while the Caliphate's patronage of scholarship and the arts fostered a vibrant intellectual atmosphere. Battganuur's strategic location made it a crossroads for trade and cultural exchange, contributing to its unique identity. The Crusades, though a period of conflict and instability, also stimulated cultural exchange and intellectual curiosity. The legacy of this era continues to resonate in Battganuur's diverse cultural heritage, its architectural treasures, and its vibrant intellectual traditions.

The Oduniyyad Caliphate's dominion over Battganuur marked a significant chapter in the region's history, characterized by a confluence of religious fervor, cultural exchange, and geopolitical conflict. This period witnessed the spread of Islam, the flourishing of intellectual and artistic pursuits, and the challenges posed by external forces, particularly the Crusades. Following the collapse of the Arunid Empire and then the Ashrafinid Empire, the Oduniyyad Caliphate swiftly extended its influence over Battganuur. The introduction of Islam, a monotheistic faith with a strong emphasis on social justice and community, profoundly reshaped Battganuuri society. Mosques sprang up across the land, replacing or coexisting with Zoroastrian fire temples and Buddhist monasteries. The Arabic language, the lingua franca of the Caliphate, gained prominence in administration, trade, and scholarship. While the initial spread of Islam was often accompanied by military conquest, it gradually became a process of cultural assimilation and religious conversion. The Caliphate's emphasis on education and social welfare attracted many Battganuuri to the new faith, leading to a gradual but significant shift in the religious landscape. The Oduniyyad period was marked by a remarkable flourishing of intellectual and artistic pursuits in Battganuur. The Caliphate's patronage of scholarship and the arts created a vibrant intellectual atmosphere, attracting scholars, poets, and artists from across the Islamic world. Cities like Alihijan and Isfahan became centers of learning, where renowned scholars and scientists made significant contributions to fields such as mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and philosophy. Battganuuri artisans excelled in producing exquisite textiles, ceramics, metalwork, and calligraphy, which were highly prized throughout the Caliphate. Battganuur's strategic location, straddling the Sea of Kandahar and bordering the Sea of Istroya, made it a vital crossroads for trade and cultural exchange. The Caliphate's vast network of roads and maritime routes connected Battganuur to distant lands, facilitating the flow of goods, ideas, and people.

The Oduniyyad Caliphate's expansion into Sarpedon brought it into conflict with Christian kingdoms, leading to a series of religious wars known as the Crusades in Audonia (1167– 1428CE). Battganuur, as a frontier region of the Caliphate, became a battleground for these conflicts. The Crusades had a profound impact on Battganuur, disrupting trade routes, causing economic instability, and exacerbating religious tensions. The region witnessed the construction of fortified castles and cities, as well as the emergence of military orders dedicated to defending the Christian faith. Despite the immense human and economic cost, the Crusades also fostered cultural exchange and intellectual curiosity. The encounter with Western ideas and technologies stimulated new developments in Battganuuri science, philosophy, and art.

Warring century

The Warring Century spanned the 15th and 16th centuries in the Daria region of Audonia. This era was marked by the tumultuous unraveling of the Oduniyyad Caliphate, factionalism, sectarian and ethnic violence, and ultimately weakened Daria making it prone to colonization by the duchies of Maritime Dericania.

Internal strife, stemming from political dissent and struggles for succession, economic stagnation and corruption progressively eroded the Caliphate's authority. The Caliphate's collapse ripped apart the fragile web of religious and ethnic cohesion that had existed under its rule. Long-simmering tensions between various groups, both religious and ethnic, flared up in the absence of a strong central authority. Communities with distinct cultural and belief systems, previously held together under the Caliphate's umbrella, found themselves at odds. This sectarian discord, coupled with competition for limited resources, fueled a period of widespread tribal and sectarian conflicts.

The power vacuum created by the Caliphate's disintegration paved the way for the rise of warlords. These opportunistic individuals, capitalizing on the prevailing chaos, carved out their own domains in strategic locations, often around cities or fortresses built by the former Caliphate. However, the reach of these warlords was limited due to the lack of a centralized tax system and the constant threat of rival factions. Their control often extended only to their immediate vicinity, creating a patchwork of small, feuding kingdoms.

The economic consequences of the Warring Century were far-reaching. The once-flourishing Silk Road became choked by rampant banditry and instability. The movement of goods became increasingly expensive and perilous. This disruption forced eastern nations, namely Daxia, to hire larger and more expensive caravan guards, some eventually became their own armies, which when coupled with Dericanian colonial expansion ism led to the establishment of the Southern Route, which bypassed the volatile Daria region altogether.

The Warring Century, spanning the 15th and 16th centuries, cast a long and ominous shadow over Battganuur, marking a period of unprecedented upheaval, fragmentation, and social unrest. The once-unified realm, held together by the Oduniyyad Caliphate, crumbled under the weight of internal strife, religious discord, and economic decline, leaving the region vulnerable to external forces and setting the stage for future colonial interventions. The seeds of Battganuur's descent into chaos were sown in the waning years of the Oduniyyad Caliphate. Political infighting, economic mismanagement, and rampant corruption eroded the Caliphate's authority, creating a power vacuum that was quickly filled by ambitious warlords and opportunistic factions. The once-vibrant cities of Battganuur, centers of trade and learning, became battlegrounds for rival groups vying for control. The collapse of the Caliphate unleashed long-suppressed religious and ethnic tensions. Shia and Sunni communities, previously coexisting under the Caliphate's umbrella, turned against each other in a bitter struggle for dominance. The Zoroastrian minority, once tolerated, faced persecution and marginalization. This sectarian strife further fragmented Battganuuri society, creating deep-seated divisions that would haunt the region for centuries. The Warring Century wreaked havoc on Battganuur's economy. Trade routes, once vital arteries of commerce, were disrupted by banditry and conflict. Agricultural production declined as fields were abandoned and irrigation systems fell into disrepair. The once-flourishing cities, symbols of Battganuur's prosperity, became impoverished and depopulated.

In the absence of a central authority, warlords emerged as the de facto rulers of various regions. These local strongmen, often backed by private armies, established their own fiefdoms, imposing their own laws and taxes. Their rule was often arbitrary and brutal, further exacerbating the suffering of the common people.

The Warring Century's devastating impact on Battganuur left the region vulnerable to external intervention. The economic decline, social unrest, and political fragmentation made Battganuur an attractive target for the expansionist ambitions of the Maritime Dericanian duchies. These maritime powers, seeking new markets and resources, gradually extended their influence over Battganuur, establishing trading posts, fortresses, and ultimately, colonial administrations. The Warring Century thus laid the groundwork for Battganuur's colonization, a process that would profoundly shape the region's destiny in the centuries to come. The legacy of this tumultuous period continues to resonate in Battganuur's complex social fabric, its diverse religious landscape, and its ongoing struggle for unity and stability.

Early modern history

-

Battganuuri boat in 1845

Starting with the fall of the Oduniyyad Caliphate in 1517 and lasting until the expulsion of the Marialanii Ularien Trading Company in 1836 and the Bourgondii Royal Trading Company in 1842, the early modern era in Battganuur was characterized by rapid development, and unprecedented resource and human exploitation.

Istroya Oriental colony

In the southern reaches of Battganuur, the Duchy of Bourgondi established the Istroya Oriental Colony in 1611. Driven by a quest for resources and strategic advantage, the Bourgondii Royal Trading Company, backed by royal decree, focused on the extraction of valuable minerals, timber, and other raw materials. The colony's administration, unlike its Marialanii counterpart, adopted a more laissez-faire approach, allowing local elites to maintain a degree of autonomy in exchange for cooperation and loyalty. This strategy, while pragmatic, also perpetuated existing social hierarchies and inequalities. The Istroya Oriental Colony, like its northern counterpart, relied heavily on slave labor. Slaves, often captured from neighboring regions were forced to work in mines, forests, and plantations, enduring harsh conditions and brutal treatment. Despite the exploitative nature of its economic system, the Istroya Oriental Colony played a crucial role in preserving the unique Istroyo-Persian culture of southern Battganuur. The Bourgondii administrators, recognizing the value of this cultural heritage, protected the Jewish communities of the former Kingdom of Eshel and promoted the use of the Istroyan language in education and administration.

Barbary Straits colony

In the wake of the Warring Century's turmoil, the Duchy of Marialanus, a rising maritime power, sought to expand its influence and commercial interests in Audonia. In 1577, the Marialanii Ularian Trading Company, armed with a royal charter, established the Barbary Straits Colony in northern Battganuur. This colony, strategically positioned at the western terminus of the Silk Road, aimed to revitalize the region's agricultural potential and capitalize on the lucrative trade routes that crisscrossed the continent. The company's administrators, drawing upon their Calvinist principles, implemented a rigid social hierarchy and a strict moral code. They invested heavily in infrastructure, constructing roads, canals, and ports to facilitate trade and transport. The colony's fertile plains were transformed into vast plantations, producing rice, cotton, and other cash crops for export. Audonian slaves, captured or purchased from neighboring regions, were forced to work on the plantations, fueling the colony's agricultural engine. The slave trade became a lucrative source of revenue for the company and its shareholders. Despite the harsh realities of colonial rule, the Barbary Straits Colony became a hub of economic activity and cultural exchange. Its port cities, such as Bandar Abbas and Bushehr, attracted merchants, missionaries, and adventurers from across Audonia and beyond. The colony's unique blend of Marialanii and Battganuuri traditions, though often fraught with tension, contributed to a vibrant and dynamic cultural landscape.

Barbary Wars

Amid the outbreak of the Barbary Wars, while much of the anti-piracy conflict was centered around the Barbary Straits between the Buroignesc Navy and corsairs hailing from what is modern Battganuur, the range of Barbary pirates stretched even further north reaching even the domain of Soirwind. Soirwind being at the time a colonial domain under what is modern day Fiannria, the spike in piracy interrupting crucial trade routes between Fiannria and Soirwind quickly drew the ire of the Levantine state. In ____ Fiannria sent a punitive expedition towards the region to combat the corsairs. Rebuffed from operating in the main combat zone and drawing too close to the Barbary Straits itself, the Fiannan war fleet set for the north towards the northern Sea of Istroya to hunt down Corsairs who broke through and expanded operations that more directly impacted Fiannria itself. The war fleet would operate between the Hezikian Isles and Soirwind for the next three years in its attempt to guard trade routes and eliminate pirate holdouts and outposts.

As the conflict in the Straits themselves raged on, the Fiannan central government would delegate more and more operational authority towards the holy orders which persisted as remants from the Crusaders and independent privateers in combating northern Barbary Piracy. This culminated in the year of _____ following the victory in the Barbary straits themselves, a large contingent of Barbary ships which survived the punitive Burgoignesc expeditions escaped to the north in order to flee arrest and execution and also find a new base of operations, instead off the southern coast of Soirwind, found a fleet of privateers and corsair chasers waiting between the coast and the island of Antilles. This fleet of holy orders, privateers and colonial defense ships from Soirwind, having gotten word of the coming fleet had gathered in the strait to attack and nip the bud of any continued corsair activity in the north. The resultant battle, the Battle in the Kamtague Narrows, saw the bulk of the remaining corsair force sunk or captured, and the remnants scattering, breaking any chance of a major Barbary incursion returning to operate in the north.

Independence, post-colonial era

The post-colonial era in Battganuur was a tumultuous period marked by political instability, economic hardship, and social upheaval. The withdrawal of Occidental powers in the late 19th century left a power vacuum, triggering a scramble for control among local elites, warlords, and religious factions. This power struggle, fueled by competing visions for the nation's future, plunged Battganuur into a protracted period of conflict and instability. This came at a pivotal time for the young Commonwealth of Fiannria. The fledgling Commonwealth of Fiannria, emerging from its own wars of independence, saw an opportunity in the nascent states of southern Battganuur. Desperate for resources and seeking to establish new trade routes, Fiannan merchants and military veterans found receptive audiences in the courts of newly independent emirs. These emirs, eager to modernize their armies and economies, welcomed the expertise and resources offered by the Fiannans. In exchange for Levantine manufactured goods, weaponry, and military training, Fiannan merchants gained access to Battganuur's vast natural resources, including oil, minerals, and agricultural products. This mutually beneficial relationship provided a crucial lifeline for both nations, allowing Fiannria to rebuild its economy and southern Battganuur to embark on a path towards modernization. The post-colonial landscape was a patchwork of competing power centers. In the north, the remnants of the Marialanii Ularian Trading Company's administration clung to power, seeking to maintain their economic interests and influence. In the south, the Bourgondii Royal Trading Company's departure left a void that was quickly filled by local leaders, many of whom were former collaborators with the colonial regime. The religious landscape was equally fragmented. Sunni and Shia Muslims, long divided by sectarian differences, clashed over political and economic power. The Zoroastrian minority, marginalized during the colonial era, sought to reassert their identity and reclaim their rightful place in society.

The collapse of colonial rule disrupted Battganuur's economy. The plantations and mines, once the backbone of the colonial economy, fell into disrepair. Trade routes, disrupted by conflict and insecurity, no longer brought the same level of prosperity. The sudden withdrawal of foreign capital and expertise left Battganuur's economy reeling. The economic hardship fueled social unrest. Peasants, burdened by high taxes and landlessness, revolted against their landlords. Workers, exploited by unscrupulous employers, organized strikes and protests. The urban poor, struggling to survive in overcrowded and unsanitary conditions, became fertile ground for radical ideologies.

Amidst the chaos and despair, a new spirit of nationalism emerged. Intellectuals, inspired by the ideals of self-determination and national unity, began to articulate a vision for an independent and unified Battganuur. They called for an end to sectarianism, an equitable distribution of resources, and a government that represented the interests of all Battganuurians. This nationalist movement, though initially fragmented and disorganized, gradually gained momentum. It drew support from diverse segments of society, including intellectuals, merchants, workers, and peasants. The shared experience of colonial exploitation and the desire for a better future united Battganuurians across religious and ethnic lines. The path towards unification was fraught with violence and setbacks. Warlords, unwilling to relinquish their power, resisted the nationalist movement, often resorting to brutal tactics to suppress dissent. Religious extremists, fueled by sectarian hatred, launched attacks on rival communities, further destabilizing the region. However, the nationalist movement persevered. Through a combination of armed struggle, political maneuvering, and diplomatic negotiation, it gradually gained the upper hand. The burgeoning alliance with Fiannria provided crucial support, both materially and ideologically, bolstering the nationalist cause and weakening the resolve of those who sought to maintain the status quo. In 1922, after decades of conflict, Battganuur was finally unified under a new government that promised to uphold the principles of democracy, equality, and justice. The Fiannan influence in this process would set the stage for a lasting relationship between the two nations, one that would continue to shape Battganuur's trajectory in the years to come.

Contemporary era

The unification of Battganuur in 1922 marked a turning point in the nation's history. The newly formed government, under the leadership of Faisal-Jallal Asayesh Aslani, embarked on an ambitious program of modernization and state-building. The scars of colonialism and the Warring Century were still fresh, but a new spirit of nationalism and optimism fueled Battganuur's aspirations for a brighter future. The early years of unified Battganuur were characterized by the consolidation of political power and the forging of a national identity. The government, though initially fragile, gradually established its authority over the vast and diverse territories of the nation. A new constitution, emphasizing unity, secularism, and the rule of law, was adopted. The Persian language, already widely spoken, was declared the official language, further solidifying the nation's cultural identity. The government invested heavily in education, establishing schools and universities across the country. The aim was to create a literate and informed citizenry capable of participating in the nation's development. The curriculum emphasized Battganuur's rich history and cultural heritage, fostering a sense of pride and belonging among the people. The government also focused on economic development, recognizing that prosperity was essential for national stability and progress. The agricultural sector, long the backbone of Battganuur's economy, was modernized through the introduction of new technologies and farming techniques. Irrigation projects were expanded, increasing agricultural productivity and ensuring food security. The discovery of oil reserves in the southern regions in the late 1920s provided a significant boost to the economy. The government, however, wary of foreign exploitation, nationalized the oil industry, ensuring that the profits would benefit the Battganuuri people. This bold move, though initially controversial, proved to be a wise decision, providing the government with the financial resources needed to invest in infrastructure, education, and healthcare. Industrialization was another key pillar of the government's economic strategy. Factories were established to produce textiles, machinery, and other manufactured goods. This drive towards industrialization not only created jobs and stimulated economic growth but also reduced Battganuur's dependence on imported goods.

Recognizing the importance of a strong military for national security, the government invested heavily in modernizing and expanding the armed forces. Battganuur's military, equipped with modern weapons (like the BP-30) and trained by foreign experts, quickly became a formidable force in the region. This military strength, coupled with Battganuur's growing economic clout, allowed it to project its influence in regional affairs. Battganuur played a key role in the formation of the League of Nations, an international organization dedicated to preventing future wars. It also actively participated in regional security alliances, seeking to maintain stability and deter potential aggressors. By 1943, Battganuur had emerged as a regional power, respected for its economic strength, military might, and cultural influence. The nation had overcome the challenges of colonialism and internal strife to forge a new path towards prosperity and progress.

The contemporary era in Battganuur has been marked by rapid modernization, urbanization, and economic transformation. The country's trajectory was significantly influenced by Operation Kipling, a series of covert operations conducted by Burgundie in the 1960s and 1970s. These operations, aimed at stabilizing Battganuur and securing its vast oil reserves, led to a close alliance between the two nations. Burgundie's investment in Battganuur's oil industry and infrastructure fueled an economic boom that lasted for several decades. New oil fields were discovered and developed, generating substantial revenue for the government. This newfound wealth was invested in infrastructure projects, including roads, railways, airports, and ports, further integrating Battganuur into the global economy. The economic boom also spurred rapid urbanization. Cities like Alihijan and Isfahan expanded rapidly, attracting migrants from rural areas seeking employment and a better life. The urban landscape was transformed by the construction of modern high-rises, shopping malls, and entertainment venues.

The rapid modernization and urbanization of Battganuur brought about significant social changes. Traditional social structures, based on kinship and community, were challenged by the rise of individualism and consumerism. The role of women in society also evolved, as more women entered the workforce and gained access to education. The cultural landscape was equally dynamic. Western cultural influences, introduced through television, movies, and music, became increasingly popular, especially among the younger generation. This led to a clash of values between traditionalists and modernists, as Battganuuri society grappled with the challenges of balancing its cultural heritage with the demands of the modern world.

Government and Politics

The Chief of Ministers, elected by the legislature, serves as the head of government and commander-in-chief of the armed forces. They are responsible for implementing policies, overseeing the executive branch, and representing Battganuur on the international stage. The Chief of Ministers' power is checked by the legislature and the supreme court, ensuring a system of checks and balances. Battganuur's legislature consists of two chambers: the Majlis (Council of Representatives) and the Senate. The Majlis, the lower house, is directly elected by the people and represents their interests. The Senate, the upper house, consists of members appointed by the Chief of Ministers and represents the various provinces and regions of Battganuur. The legislature is responsible for making laws, approving the budget, and overseeing the executive branch. The Supreme Court is the highest judicial authority in Battganuur. Its justices are appointed by the Chief of Ministers with the approval of the Senate. The Supreme Court's role is to interpret the constitution, uphold the rule of law, and ensure that the actions of the government are in accordance with the constitution.

Subdivisions

- Ahabijan

- Andivaz

- Takand

- Maradan

- Kangadasht

- Kamanikand

- Khoraz

- Malarand

- Salamnijan

- Oros

- Jirohriar

- Kiliam

- Kilarand

- Oruftijan

- Asakhs

- Bonadbar

- Nahaqqez

Alihijan Capital District

Capital city, most populated city in Battganuur.

Military

The Battganuuri Armed Forces (BAF), known as Artesh-e Battganuur in Persian, are a modern and well-equipped military organization entrusted with safeguarding the nation's sovereignty, maintaining internal security, and projecting power in the Middle seas region. With a rich history and a commitment to technological advancement, the BAF plays a crucial role in Battganuur's national defense strategy and its geopolitical aspirations.

The BAF is divided into four main branches:

- Artesh (Army): The largest branch, responsible for ground operations and territorial defense. It is organized into several corps, divisions, and brigades, equipped with a mix of domestically produced and imported weapons systems.

- Niruy-e Daryayi (Navy): Tasked with protecting Battganuur's extensive coastline and maritime interests. It operates a fleet of frigates, corvettes, submarines, and patrol vessels, supported by naval aviation and marine corps units.

- Niruy-e Havayi (Air Force): Provides air superiority, air defense, and ground support to the other branches. It operates a diverse fleet of fighter jets, bombers, transport aircraft, and helicopters, sourced from various countries.

- Niruy-e Vizheh (Special Forces): An elite unit trained for unconventional warfare, counter-terrorism, and special reconnaissance missions. Its operators are highly skilled and equipped with cutting-edge technology.

The BAF is an all-volunteer force, with a strong emphasis on professionalism and training. Conscription is not mandatory, but all citizens are encouraged to undergo basic military training as part of their civic duty. The BAF's training programs are rigorous and comprehensive, covering a wide range of skills, including combat tactics, weapons handling, logistics, and leadership. The BAF also places a high value on education, offering its personnel opportunities to pursue higher education and professional development. This commitment to education has fostered a highly skilled and adaptable workforce, capable of operating in a complex and rapidly changing security environment.

The BAF is equipped with a diverse range of modern weapons and technology, sourced from both domestic and foreign suppliers. The army's arsenal includes tanks, armored vehicles, artillery, and missile systems. The navy operates a mix of domestically produced and imported vessels, equipped with anti-ship missiles, torpedoes, and electronic warfare systems. The air force's fleet includes fighter jets, bombers, transport aircraft, and helicopters, sourced from various countries including Burgundie, Fiannria, and Levantian powers. Battganuur's defense industry has also grown significantly in recent years, producing a range of weapons systems and equipment for the BAF. This domestic production has reduced Battganuur's dependence on foreign suppliers and enhanced its strategic autonomy.

The BAF is a major player in the Middle seas region, projecting power and influence through its participation in regional security alliances and peacekeeping operations. It has also played a key role in combating terrorism and piracy in the region, contributing to regional stability. However, the BAF also faces several challenges. The ongoing tensions with neighboring countries, such as Bulkh and Umardwal, require a constant state of vigilance and preparedness. The threat of terrorism, both domestic and international, remains a major concern. The BAF must also adapt to the rapidly evolving nature of warfare, investing in new technologies and training to maintain its edge.

Society

Battganuur is a predominantly Muslim country, with the majority of the population adhering to Sunni Islam. However, significant Shia Muslim, Jewish, and Christian minorities also contribute to the nation's religious landscape. This religious diversity is reflected in the country's cultural practices, festivals, and traditions. Battganuur's cultural identity is deeply rooted in its Persian heritage. The Persian language, literature, and art have shaped the nation's cultural expression for centuries. The influence of Persian poetry, calligraphy, and architecture is evident in Battganuur's vibrant cultural scene. The Istroyan legacy, particularly in the southern regions, also plays a significant role in shaping Battganuuri culture. The coastal cities, with their distinct Istroyo-Persian architecture, cuisine, and cultural practices, bear witness to this historical influence. Battganuur's rapid modernization and urbanization have led to significant cultural shifts. Western cultural influences, introduced through media, education, and tourism, have become increasingly prevalent, particularly among the younger generation. This has led to a dynamic interplay between tradition and modernity, as Battganuuri society seeks to balance its cultural heritage with the demands of the modern world. Family and community remain central to Battganuuri society. The extended family unit plays a vital role in social support, providing emotional, financial, and practical assistance to its members. Community gatherings, festivals, and religious ceremonies are important occasions for social interaction and cultural expression. Traditional gender roles are still prevalent in Battganuur, with women often expected to focus on domestic responsibilities and men on breadwinning. However, this is changing as more women enter the workforce and pursue higher education. The government has also implemented policies aimed at promoting gender equality and empowering women. Battganuur faces several social challenges, including income inequality, poverty, and limited access to education and healthcare, particularly in rural areas. The government has implemented various social welfare programs to address these issues, but much work remains to be done. Despite these challenges, Battganuuri society is characterized by a strong sense of resilience, optimism, and a deep-rooted pride in its cultural heritage. The nation's young and dynamic population aspires to a better future, one that combines economic prosperity with social justice, cultural diversity, and environmental sustainability.

Battganuur has a rich tradition of arts and literature, encompassing music, dance, theater, cinema, and visual arts. Persian poetry, calligraphy, and miniature painting are highly regarded forms of artistic expression. Contemporary Battganuuri artists and writers are also gaining recognition on the international stage, exploring themes of identity, social change, and the challenges of modernity. Battganuuri cuisine is a delightful fusion of Persian, Arab, Turkish, and Indian influences. Rice is a staple food, served with a variety of curries, stews, and grilled meats. Spices, herbs, and dried fruits are used liberally, creating a symphony of flavors and aromas. Battganuuri desserts, such as baklava, halva, and saffron ice cream, are renowned for their sweetness and richness.

Architecture

Battganuur's architectural landscape is a captivating blend of ancient traditions, diverse cultural influences, and modern aspirations. From the intricate geometric patterns of Islamic mosques to the imposing grandeur of Occidental-inspired palaces, Battganuur's buildings tell a story of its rich history, diverse cultural heritage, and ongoing journey towards modernity. The remnants of ancient and classical civilizations can still be seen in various parts of Battganuur. In the northern regions, the ruins of Arunid Empire structures, such as the imposing fortresses and intricately carved stone pillars, stand as a testament to the empire's architectural prowess. The influence of ancient Persian architecture is also evident in the region's traditional houses, characterized by their mud-brick construction, courtyards, and wind towers for natural ventilation. In the southern coastal regions, the Istroyan influence is prominent, particularly in the cities of Bandar Abbas and Bushehr. Here, one can find the ruins of ancient Istroyan temples, theaters, and agorae, as well as later buildings that blend Istroyan and Persian styles. These structures often feature columns, arches, and domes, adorned with intricate mosaics and sculptures. The advent of Islam in the 7th century CE marked a significant turning point in Battganuur's architectural history. Mosques, with their distinctive minarets, domes, and geometric patterns, became prominent features of the urban landscape. The Jameh Mosque of Isfahan, a masterpiece of Islamic architecture, is a prime example of the intricate tilework, calligraphy, and geometric designs that characterize this style. Other notable examples of Islamic architecture in Battganuur include the Imam Reza shrine in Mashhad, the Vakil Mosque in Shiraz, and the Golestan Palace in Tehran. These buildings showcase the diverse regional styles of Islamic architecture, from the Seljuk and Safavid eras to the Qajar period. The colonial era, particularly in the southern regions, introduced Occidental architectural styles to Battganuur. The Bourgondii Royal Trading Company built imposing administrative buildings, palaces, and churches in a neoclassical style, reflecting the architectural trends of the time. These buildings, though often symbols of colonial power, also contributed to the diversity of Battganuur's architectural landscape. In the 20th century, with the rise of nationalism and modernization, Battganuur's architecture underwent a significant transformation. Modernist buildings, inspired by Occidental and American styles, began to appear in major cities. These buildings, often characterized by their clean lines, functional design, and use of concrete and steel, reflected the nation's aspirations for progress and modernity. In recent decades, Battganuur's architecture has become increasingly diverse and innovative. Contemporary architects are experimenting with new materials, technologies, and design concepts, creating buildings that are both functional and aesthetically pleasing. The Azadi Tower in Tehran, a monument to Iran's independence, is a prime example of this modern architectural vision. The development of family resorts, catering to both domestic and international tourists, has also spurred a new wave of architectural creativity. These resorts, often located on the coast or in scenic mountain regions, feature a variety of architectural styles, from traditional Battganuuri designs to modern minimalist villas. Battganuur's architectural landscape is a testament to its rich history, diverse cultural heritage, and ongoing journey towards modernity. It is a dynamic and evolving tapestry, reflecting the nation's aspirations, challenges, and creative spirit.

Economy and infrastructure

Standard of living and employment

Battganuur's standard of living has improved significantly in recent decades, driven by economic growth and government investment in social welfare programs. However, income inequality remains a significant challenge, with a large portion of the population still living in poverty. Access to education, healthcare, and basic infrastructure also varies widely across the country.

Tourism

Tourism is a burgeoning sector in Battganuur, attracting visitors with its diverse landscapes, rich cultural heritage, and modern amenities. The country's beautiful beaches, ancient ruins, and vibrant cities offer a unique blend of attractions. Family resorts, catering to both domestic and international (primarily Audonian) tourists, are a major draw, generating significant revenue for the economy.

Agriculture

-

Rice

-

Cattle

-

Cashews

-

Mangoe latifundia

Agriculture remains a cornerstone of Battganuur's economy, employing a significant portion of the population and contributing substantially to the nation's GDP. The fertile plains of the northeast are dominated by rice cultivation, with over 26 million hectares of paddy fields producing an average of 117 million tons of rice annually. Battganuur is a major rice exporter, with around 100 million tons shipped to international markets each year. Other important agricultural products include cashews, mangoes, bananas, plantains, and rubber. The drier western regions are ideal for cashew cultivation, while mangoes thrive in the west and bananas and plantains are grown in the northeast. Rubber plantations, located in the humid northeast, produce a significant amount of rubber for export. Livestock rearing, particularly cattle and goats, is also a significant agricultural activity, contributing to both domestic consumption and exports. The fishing industry, utilizing both modern fleets and traditional techniques, harvests a vast array of fish species from the surrounding waters, with a significant portion exported to international markets.

Rice: Around 26 million hectares of rice paddy land stretch across fertile plains of the northeastern provinces of Ahabijan, Andivaz, Takand, Maradan, and Malarand. Over 52 million people are employed in rice cultivation making it one of the largest employment sectors in the country. The rice sector yields an average 117 million tons annually, around 100 million tons, is exported, making it a critical pillar of the economy of the country.

Cashews: In the drier western part of the country, cashew trees thrive. Traditional methods prevail which involve hand-harvesting, sun-drying, and shelling the nuts, resulting in an export of around 200,000 tons each year.

Mangoes: Mangoes are grown in the country's west. Farmers utilize grafting techniques and careful water management to cultivate diverse varieties. An estimated 1 million tons of mangoes are produced annually, with around 700,000 tons exported.

Bananas and Plantains: Bananas and plantains grown in the northeast of Battganuur. Farmers employ sustainable practices like intercropping and organic fertilizers to cultivate around 2 million tons of bananas and plantains combined. Roughly 1 million tons find their way to international markets.

Rubber: Rubber latifundia thrive in the humid northeast. Skilled workers carefully extract latex using sustainable tapping methods, producing an estimated 300,000 tons of rubber annually. Around 250,000 tons are exported.

Cattle and Goats: Roaming freely across vast pastures in the west and southeast, cattle and goats are raised by herders. Traditional practices like rotational grazing and selective breeding ensure animal welfare and sustainability. Battganuur exports around 100,000 tons of beef and 50,000 tons of goat meat annually.

Fishing: The coastal waters surrounding Battganuur teem with diverse fish species. Modern fishing fleets and traditional techniques, maintain a catch of around 500,000 tons annually. Around 300,000 tons are exported.

Guar and guar gum: worlds largest producer

Tea

Battganuur is a major producer of tea.

Agrinergie

Main article: Agrivoltaics Battganuur began to embrace agrinergie in 2016 when the Agricultural University of Maradan State partnered with the Burgoignesc Gaia Energy Corporation, and the local utility company on a project to bring power to isolated communities in the Northern Marashrra Mountains. The project was a success and it expanded across the western and southern parts of the country. These agrivoltaic projects have been resource intensive because, starting in 2025, Battganuur required them to create or connect to a micro-grid. Since the existing grid was subpar in many rural areas this requirement meant that in many areas entirely new grids were created. While this has slowed the expansion of agrivoltaic projects across the country, it has created a much higher resiliency in the communities where they are install. Agrivoltaics cover 33.7 hectares of farmland and generate around 250MW of power for local communities who were previously underserved or not at all connected to the national power grid.

Battganuur is a pioneer in "vertical agrivoltaics" system, solar cells are oriented vertically on farmland. In 2022, Agricultural University of Maradan State partnered with the Burgoignesc Gaia Energy Corporation piloted a vertical agrivoltaics project with bifacial vertical solar panel (BVSP) array in a corporate latifundia. The pilot proved 3-4% more efficient than the standard horizontal array layout. They were also able to double the total amount of photovoltaic coverage of the of the same acreage. Between 2025-2032 14 hectares of BVSPs were installed representing over 40% of the total agrinergie arrays in Battganuur.

Logging/Mineral extraction

Battganuur is endowed with rich mineral resources, including diamonds and other precious stones. The mining sector, though relatively small, contributes significantly to the nation's export earnings. The forestry sector, concentrated in the northeast, is a major producer of tropical hardwoods such as teak, mahogany, ebony, rosewood, and padauk. These woods are in high demand for furniture, construction, and decorative purposes, and Battganuur is a leading exporter of these valuable commodities.

Logging

The tropical hardwood forestry is centered in the provinces of Ahabijan, Andivaz, Takand, Maradan, and Malarand. The primary woods cultivated and logged are teak, mahogany, ebony, rosewood, and padauk. Battganuur's timber industry is dominated by large companies employing advanced machinery in well planned plantations. In total, it employs around 320,000 people. Buttganuur logs 3 million tons of teak annually, around 2.5 million tons are exported. This sector employs an estimated 150,000 people directly in cultivation, logging, and processing. 2 million tons of mahogany are logged annually, Battganuur exports around 1.8 million tons. The mahogany sector employs an estimated 120,000 people across various stages of the industry. While Battganuur harvests around 300,000 tons of ebony annually, only 200,000 tons are exported due to strict regulations and conservation efforts. This sector employs approximately 25,000 people, with a focus on responsible harvesting and community involvement. Renowned for its intricate grain and vibrant colors, rosewood cultivation and logging are closely regulated in Battganuur. Large companies cultivate and harvest around 150,000 tons annually, exporting only 100,000 tons due to international restrictions on endangered species. This sector employs around 10,000 people, with a strong emphasis on sustainable practices and ethical sourcing. Known for its reddish-orange hue and durability, padauk cultivation remains limited due to its slower growth rate. Large companies manage smaller plantations, producing around 200,000 tons annually and exporting 150,000 tons. This sector employs around 15,000 people, focusing on research and development for faster-growing padauk varieties while maintaining responsible practices.

West dry tropical area: acacia, neem, and some sal varieties. Sustainable management and focus on value-added products like furniture and veneers would be key.

Southeast: mesquite or acacia, but small scale

Rubber is a key sector in Battganuur's economy. Located in the nation's humid northeast, the provinces of Ahabijan, Andivaz, Takand, Maradan, and Malarand, host massive rubber plantations, managed by both large-scale companies and smaller family farms, thrive under the monsoon rains. While Hevea brasiliensis, the Pará rubber tree, is the king shit. The annual production is 300,000 tons, Battganuur is one of the largest exporters in the global rubber market.

Manufacturing

The manufacturing sector has grown rapidly in recent years, driven by government investment and foreign direct investment. The military-industrial complex, producing a range of weapons systems and equipment for the Battganuuri Armed Forces, is a major player in this sector. Other important industries include textiles, food processing, and electronics.

Nuradaj MILCAR plant

In 2015, MILCAR opened a plant in Nuradaj, Battganuur. This plant builds the passenger variant Jornaleros used by many louage services in the Daria region of Audonia. They plant also includes repair facilities to maintain the buses they build. The plant employees about 1,000 people as is intentionally unautomated as a way to provide employment opportunities. Due to the wage differential between Pelaxia and Battganuur the plant is still profitable for the Pelaxian company.

Trade

Trade and exports play a pivotal role in Battganuur's economy, fueling its growth, generating revenue, and connecting it to the global marketplace. The nation's strategic location, diverse natural resources, and growing industrial base have positioned it as a major exporter of agricultural products, minerals, manufactured goods, and services. Battganuur's fertile lands and favorable climate make it an agricultural powerhouse. Rice, the country's most significant agricultural export, is cultivated on vast paddy fields in the northeast and shipped to markets across Audonia and beyond. Other major agricultural exports include cashews, mangoes, bananas, and plantains, which are grown in various regions of the country and prized for their quality and flavor. The rubber industry, concentrated in the humid northeast, is another major contributor to Battganuur's export earnings. The country is one of the world's largest producers of natural rubber, supplying global markets with this essential commodity. Battganuur's livestock sector, particularly cattle and goats, also contributes to export revenues. The country's vast pastures support a thriving livestock industry, producing high-quality beef and goat meat for both domestic consumption and export. The fishing industry, utilizing modern fleets and traditional techniques, harvests a wide variety of fish and seafood from the surrounding waters, further diversifying the country's export portfolio. Battganuur's rich mineral resources, including diamonds and other precious stones, are a significant source of export revenue. The mining sector, though relatively small, plays a crucial role in generating foreign exchange and boosting the country's economic growth. The forestry sector, concentrated in the northeast, is a major producer and exporter of tropical hardwoods. Teak, mahogany, ebony, rosewood, and padauk are highly sought-after for their durability, beauty, and versatility, commanding premium prices in international markets. Battganuur's manufacturing sector has grown rapidly in recent years, driven by government investment and foreign direct investment. The military-industrial complex, producing a range of weapons systems and equipment, is a major player in this sector. Other important industries include textiles, food processing, electronics, and pharmaceuticals. These manufactured goods are exported to a wide range of countries, contributing to Battganuur's economic diversification and resilience.

Battganuur's major trading partners include Burgundie, Fiannria, and other countries in the Middle seas region. The country has also signed several trade agreements with other nations, aimed at reducing trade barriers and promoting economic cooperation. These agreements have helped to boost Battganuur's exports and integrate its economy into the global marketplace.

Infrastructure

-

Louage station

The infrastructure of Battganuur is a mix of modern and developing systems, reflecting the country's emerging market status and its reliance on foreign investment. Significant improvements have been made in recent decades, particularly in the areas of transportation and telecommunications, due in part to investments from Burgundie during Operation Kipling in the 1960s-early 1980s.

Energy

Battganuur's energy sector is predominantly reliant on fossil fuels, particularly coal and natural gas, for power generation. However, there has been a growing trend towards renewable energy sources like hydropower, solar, and wind power, as well as biofuels, since the 1990s. The government has set targets to increase the share of renewables in the energy mix, but challenges remain in terms of financing and infrastructure development.

Transportation

- Railways: Battganuur uses Standard gauge, 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) as most of its rail infrastructure has been under the auspices of Burgundie and its sphere of influence in the Middle seas region, who all use that rail gauge. Its network connects major cities and industrial centers. The system is primarily used for freight transportation, especially for agricultural products and minerals. Passenger services are limited and primarily focused on intercity routes. The railway infrastructure is maintained by Battganuur Railways, which is owned by Tierradorian and Burgoignesc-funded Umardo-Tapakdori National Rail, which is responsible for maintaining 1,678 kilometers of Battganuur's extensive railway system.

- Highways: The country has a relatively extensive road network, connecting major urban areas and economic centers. However, the quality of roads varies significantly. While major highways are paved and well-maintained, many rural roads are unpaved and can become difficult to navigate during the monsoon season. The government has undertaken projects to improve and expand the road network, with funding from international donors.

- Ports: Battganuur has several ports along its coastline, which play a crucial role in the country's international trade. The main ports are located at Tarigar, the largest city, and at Sarkar, the capital. These ports handle a variety of cargo, including agricultural products, minerals, and manufactured goods.

- Airports: There are several airports in Battganuur, including international airports at Tarigar and Sarkar. These airports are served by both domestic and international airlines, providing connections to major cities in the region and beyond.

- Ferries: Ferries play an important role in domestic transportation, connecting the mainland with the various islands that make up the country. Passenger ferry services are primarily focused on domestic travel, but some routes extend to neighboring Tapakdore.

Louage

A louage is a minibus shared taxi in many parts of Daria that were colonized by Burgundie. In Burgoignesc, the name means "rental." Departing only when filled with passengers not at specific times, they can be hired at stations. Louage ply set routes, and fares are set by the government. In contrast to other share taxis in Audonia, louage are sparsely decorated. Louages use a color-coding system to show customers what type of transport they provide and the destination of the vehicle. Louages with red lettering travel from one state to another, blue travel from city to city within a state, and yellow serves rural locales. Fares are purchased from ticket agents who walk throughout the louage stations or stands. Typical vehicles include: the MILCAR Jornalero, the TerreRaubeuer Valliant 130, and the CTC M237-07.

Telecommunications

Battganuur's telecommunications infrastructure has seen significant development in recent years, with increasing mobile phone penetration and expanding internet access. The state-owned Battganuur Telecom is the largest provider, but there is growing competition from private operators. The government has launched initiatives to expand broadband access in rural areas and improve the overall quality of service.

See also