Crusades

This page is currently undergoing major reconstruction in accordance with broader lore changes. |

The Crusades were a series of religious wars sanctioned by the Catholic Church in the medieval period. The most commonly known Crusades are the campaigns on the continent of Sarpedon aimed at restoring Christian Istroya, but the term "Crusades" is also applied to other church-sanctioned campaigns. These were fought for a variety of reasons including the suppression of paganism and heresy, the resolution of conflict among rival Levantine Catholic groups, or for political and territorial advantage.

Background

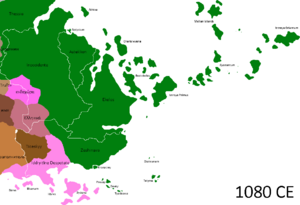

From the 7th to the 11th century, the Oduniyyad Caliphate, which unified Audonia under the banner of Islam, spread across the known world. The Melian Islands were taken by the Caliphate in 728 which lead to a century of large scale invasions into eastern Sarpedon, followed by subsequent campaigns by individual adventurers to establish their own Caliphate-tributary realms in Sarpedon. The collapsing authority of Caphiria during this period made the continent especially vulnerable. Due to the strategic location of the islands in the Sea of Istroya and prevailing winds, Caliphal campaigns were waged with relative logistic ease. By the middle of the 11th century, the entire ancient Istroyan world and eastern Sarpedon had been conquered by the Caliphate. The dynastic feuding and civil wars of the Caliphate beginning in the 11th century lead to the destruction of Christian holy sites in the Melian Islands, enraging the Christian world and leading to social and political calls for retaliation.

Istroyan Crusades (1084–1314)

First Crusade (1084)

Pope Gregory VII first preached the Reconquest of Sarpedon's lost lands in 1084 as a "Christian emergency." One of the first to answer the call of arms was the Emperor of the Levantines, Carles II. His recruiting and campaigning efforts resulted in his canonization and veneration as a Catholic saint in 1297. The initial Crusades included large scale campaigns on Sarpedon's mainland which were largely unsuccessful but victorious in taking the Odouneru Ocean and Sea of Istroya islands which connected the Caliphate to its possessions and dependencies in Sarpedon. The primary success was in the Crusade's preliminary operation. Emperor Carles II dispatched the crusader Guy of Idalè to take the island of Halfway which would serve as a staging ground for the full Crusader force from Levantia. Accordingly, Count Guy invaded Halfway in mid 1084 and, following a yearlong campaign, subdued the island and established the Principality of Halfway in 1085. The crusader army then began to gather on the island and, after some logistical difficulties, crossed over to Sarpedon in 1086. The army failed to defeat a Caliphal army but nonetheless took enough major cities and garrisons in Thessia and Herciana to secure a favorable peace. Though the peace was far short of resolving the "Christian emergency" and liberating the continent from the Caliphate, it nonetheless proved the viability of the crusading idea and provided a staging point for future conflicts.

Some of the lands taken during the first Crusade included Halfway, Herciana, and parts of modern Thessia, though Caliphal armies were undefeated in the field and these lands were largely possessions of independent adventurers and were Caliphal tributaries. Several Crusader states were established in these lands, most prominently the Principality of Halfway. Despite being inherited by House de Weluta of Urcea in 1474, the Principality was mostly left to govern its own affairs until it was folded into the Kingdom of Crotona in 1660. Existing for nearly half a millennia, the Principality's legacy survives through today; the title of the heir to the Apostolic King of Urcea is Prince of Halfway, indicating the high esteem placed on the long lasting Crusader state.

Second Crusade (1113)

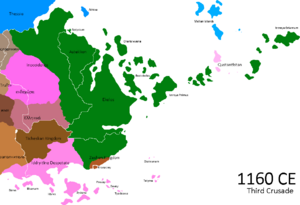

The Second Crusade saw the Melian Islands attacked by the Crusaders, but the offensive bogged down in a long siege that was ultimately unsuccessful. Some minor islands in the Sea of Istroya were taken by the Crusaders, but its overall mission of cutting the Audonia-Sarpedon connection failed. It was the last time the Caliphate was able to launch a major campaign using Audonian resources in Sarpedon.

Third Crusade (1144)

The Third Crusade (1144) had significant and long-lasting effects on the balance of power between Sarpedon and Audonia. The Crusaders managed to capture the Melian Islands and supported an uprising of the Qustanti Muslims living in the southern islands, and their alliance completely severed the connection between the emirs of Sarpedon and the western Caliph to whom they owed allegiance. The Third Crusade began the era of the independent emirates, a situation which would become de jure with the destruction of the western Caliphate in 1153. On mainland Sarpedon, Islamic control was pushed back roughly to the modern eastern border of Caphiria.

Fourth Crusade (1180)

The Fourth Crusade made significant gains on mainland Sarpedon against the emirs and, critically, conquered all of the remaining islands in the Sea of Istroya, completely removing the Caliphate's influence in Sarpedon.

In Audonia (1167–1428)

Many scholars consider the Audonian Crusades as a continuation of the Crusades in Sarpedon, as its driving power was following up on the successes of the Levantine Catholic forces against Islamic holdings in southern Sarpedon. While largely ineffective, a remaining legacy was the establishment of a Catholic Crusader state in Antilles.

Crusades in Battganuur

Crusades in Umardwal

Between 1304 and 1416 there were 4 crusades in the Caliphate province of Umalia, in northern Umardwal. The once great port cities were sacked in 1304, 1354, and 1416. The 1373 crusade was a disaster for the Occidentals. The region was able to recover in 1304 and 1354 but the efforts taken to repel the crusaders in 1373 and a generally collapsing empire caused the Caliphate to give little aid to Umalia after 1381.

Khazan Crusade

Historians are divided on whether or not the Levantine campaign in Khaza could be considered part of the Crusades. Most correspondence indicates the intention of supporting the native Jewish rebellions as part of a broader strategic vision of creating a buffer zone against the Caliphate on the coast of the Sea of Istroya. As mentioned, these efforts were largely in support of Jewish rebels, and the creation of a longterm Crusader state in the region was deemed to be unfeasible and undesirable, which in part explains the lack of unity and motivation among the crusaders. A majority of historians do include the campaign within the Crusades because it supported the overall strategic efforts of the Crusade even if the establishment of Christian rule was not among its chief objectives.

Impacts

Sea of Istroya trade network

After 1291

Northern Crusades (1396–1574)

Conquest of Joanusterre (1458-1574)

In the mid 15th century the Knights of the Order of the Obsidian Sparrow, having missed its opportunity to prove itself as an order in the Audonian Crusades, sought their fortune in Northern Levantia. They convened in western Culfra with 1,800 knights under Knight Commander Joanus de Martigueux the third son of the Count of Estia. de Martigueux's army crossed into Ultmar, the general name for Northern Levantia that was not incorporated into the Holy Levantine Empire, and began a campaign to convert by "the Book or by their blood" the conquest and conversion of modern Yonderre. By 1464 they had established a minor crusader kingdom on the southern coast of the Vandrach. They established trade with the Kingdom of Magnia-Gabben in 1475 and solidified its position as an autonomous marcher kingdom in a treaty with the Holy Levantine Empire in 1494, known as the Treaty for the guarantee of Joanus' Land. Due to the varieties of languages spoken by the Knights of the Order of the Obsidian Sparrow, a variety of spellings of each name were utilized by the scribes of the Order. A common spelling of the Knight Commander's name was Yoanus and the Latin Joanusterrium used in the treaty language was later shortened to Yoansterre. In 1497, de Martigueux was made Knight Grand Cross and given the title Grand Officer-Count of Joanusterrium. Upon his death the title was given to his second in command, Knight Commander Mattius-Arnuald Egide de Houicourt. This investiture of the appointed deputy of the Grand Officer-Count was observed by the order until the county was raised to a duchy by the Pope in 1574 both for having increased in size but also for its proselytizing efforts in the region.

de Houicourt sought not only to expand the order's influence in the region but also to administer the conquered land. He established knights in fiefdoms and supported them in the construction of keeps. His rule was supported by an influx of additional knights and general adventurers in the mid 16th century. He also supported the admission of local Gothian leaders joining the order and promoting them equitably. The ranks of the Order of the Obsidian Sparrow swelled and eventually the Grand Magisterium was concerned that the "northern knights" were becoming more loyal to de Houicourt than the order and threatened to expel him and seek his excommunication if he did not resign. He resigned but wrote the Pope to implore that the "vainglorious ineptitude of the leadership of the Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John, that established the Order of the Obsidian Sparrow has infected the Sparrows and threatens Christ's work in Joanusterrium." The Pope came to de Houicourt's aid and had him reinstated and further conferred on him and the County the titles of Most Serene.

With its elevation to Most Serene Duchy in 1574, the Most Serene Grand-Officer Duke Marcus Antonius was also elected as the Grand Master of the Order. This, lead to an almost 150 period of "northern knights" leading the Order. This also formally ended the "crusading" era in Joanusterrium and started the era of "administration".

Highland Crusades

Against Christians

Kurikilan Crusade

The Kurikilan Crusade was an extension of the First Princes' War in Faneria, and a direct defiance of the peace made afterwards by the Wydd-Màrtainn branch of the royal line. The First Princes' War was fought over religious tolerance of protestant sects in Faneria and its surrounds as much as over succession rights and noble privilege, and resulted in a large number of protestants surrounding a sect in the city of Kurikila attempting to create an independent holy state, refusing to accept rule by a Catholic monarch. In response, a several years-long siege of the region was undertaken, eventually resulting in a number of massacres of protestant congregations, a refugee crisis, and a brief period of the Wydd-Màrtainns reneging on their promises to protestant elements of the nobility followed by decades of tension. The region was later populated heavily with colonists from eastern Faneria, creating a large mixed culture in the west and blotting out Protestant remnants in the area.

Tonsure Wars

Considered a proto-Crusade, the Tonsure Wars were a series of doctrinal and military conflicts between Latinic Alvarians and the Gaelians in Northern Levantia in the 8th century. It was named for the style of monastic tonsure worn by the clergy of each ethnic group. Alvarians monks wearing the coronal tonsure espousing a direct and puritanical application of Catholic rites and the Gaelians monks wearing the Celtic tonsure and embracing a more colloquial form of Catholicism. At the insistence of the clergy in Alvaria, in 738 an edict was passed that all monastic orders in Gaelia must conform to the "regular traditions and trappings of the Papal orders" with specific language regarding the cutting of hair and the wearing of plain robes, not to be colored in the "patterns of the forest". The edict was largely ignored as the Alvarians had no interest in enforcing the ruling and the clerics had no jurisdiction. In 754, a group of monks and mercenaries set out from Marialanus to "implore" Gaelian monks along the border to conform to the edict. The mercenaries looted the monasteries and got drunk on the beer and wine causing havoc and the venture was called off. In 768, another party was formed, this time with the blessing of the Archbishop of Rabascall, and the monks themselves had been given dispensation to take up arms. Additionally, the Pope had declared Celtic Christianity a pagan and blasphemous church the year before. This gave the monks dispensation to convert or "dispatch to God's judgment" the monks of Gaelia. The warrior monks descended upon the border regions and attacked a number of churches. The King of Gaelia formed and army and dispatched the Alvarian monks quickly. The Pope saw this as the temporal kingdom taking arms against Catholic Church and the Alvarian and Fanerian armies were called to bring the Gaelians back into the fold. A series of battles ensued and Gaelia was greatly diminished to the benefit of Alvaria and Faneria. In 783, the edict of 738 was adopted across Gaelia and the practice of shaving the Celtic tonsure ended as a common practice. Some remote monasteries continued the practice into the 1200s but it eventually fell out of style. The practice reemerged in the 1830s after the Northern Levantine Mediatization War and continues in some places to this day. Celtic tonsure and other distinctively Celtic Christian practices would continue uninterrupted in the Kiravian lands under the auspices of the Insular Apostolic Church, which by virtue of its remoteness was able to defy the edict of 738 and welcomed Gaelian dissenters.

Venceian Crusade

From the 17th through the 20th century, a purportedly planned 13th century Venceian Crusade was widely believed throughout most of the Occident. The Crusade, intended to conquer the former Caphirian heartlands for Levantines, was most likely a post-Great Schism invention of Caphiric Church clerics. This Crusade became a central point in most histories of Levantine Creep.