St. Nicholas Colony: Difference between revisions

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

||

| Line 97: | Line 97: | ||

==Economy== | ==Economy== | ||

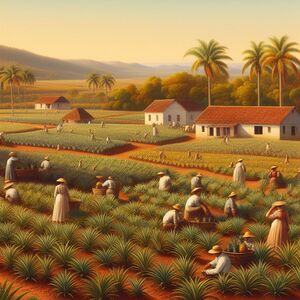

[[File:St.NickColonyPineappleLatifundia.jpeg|thumb|right|Pineapple Latifundia in St. Nicholas Colony, [[1743]].]] | |||

The colony was heavily reliant on the cultivation of sugar cane and pineapples, primarily for export. It acted as a vital intermediary trading post between the Martillien colonies of [[Veraise colony]], [[Credesia colony]], and the Bourgondii colony of [[Equatorial Ostiecia]]. St. Nicholas Colony was deeply embroiled in the slave trade, utilizing enslaved labor for the cultivation of crops. | The colony was heavily reliant on the cultivation of sugar cane and pineapples, primarily for export. It acted as a vital intermediary trading post between the Martillien colonies of [[Veraise colony]], [[Credesia colony]], and the Bourgondii colony of [[Equatorial Ostiecia]]. St. Nicholas Colony was deeply embroiled in the slave trade, utilizing enslaved labor for the cultivation of crops. | ||

Under the dominance of the ethnically [[Bergendii]] Martilliens, the native population and slaves were subject to harsh, oppressive rule. St. Nicholas Colony's capital and primary port Havre de Grace, served as a critical port for ships to dock for necessary replenishments and repairs, enhancing its strategic importance in the colonial trade network of the era. | Under the dominance of the ethnically [[Bergendii]] Martilliens, the native population and slaves were subject to harsh, oppressive rule. St. Nicholas Colony's capital and primary port Havre de Grace, served as a critical port for ships to dock for necessary replenishments and repairs, enhancing its strategic importance in the colonial trade network of the era. | ||

Revision as of 09:11, 23 October 2023

| This article is a stub. You can help IxWiki by expanding it. |

St. Nicholas Colony Colonie St. Nicholas | |

|---|---|

| 1654-1899 | |

|

Flag | |

| Status | Colony of the Duchy of Bourgondi |

| Official language | Burgoignesc |

| Religion | Calvinism, Lutheranism, Presbyterianism |

| Government | Constitutional monarchy |

| Historical era | Age of Discovery, Age of Sail |

• Established | 1654 |

• Disestablished | 1899 |

| Today part of | |

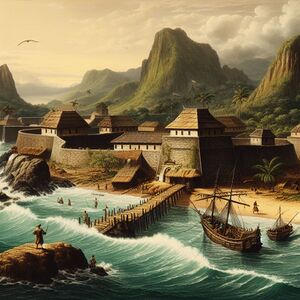

Seváronsa was visited by traders of various nationalities early in the Age of Exploration, though Bergendii and Kiravians were the most frequent callers. The Bergendii navigator Jean-Zechariah Gullouing deLoreanne purchased the area enclosing a commodious natural harbour on Great Seváronsa from the native chief Bumi the Duped in exchange for an assortment of Levantine manufactures, including 11 leather boots (5 pairs and 1 lone right boot), four ear spoons, and two hats. There deLoreanne established a trading post and way station which he dubbed Havre de Grace. Burgundie achieved suzerainty over Great Seváronsa in 1654 and called it St. Nicholas Colony, which was later extended to the other two islands, which were collectively absorbed into the Burgoignesc Thalattocracy in 1876 after the unification of Burgundie following the First Fratricide.

Establishment

The founding of St. Nicholas Colony was intricately tied to the influx of Presbyterian settlers seeking refuge following the Expulsion of the Protestants triggered by the tumultuous Great Confessional War in the Holy Levantine Empire. Driven by religious persecution and the desire for religious autonomy, these Presbyterian refugees established the colony as a haven for their faith and a sanctuary from the religious conflicts that plagued their homeland.

The early days of the colony were heavily influenced by the tenants of their Presbyterian faith, which emphasized principles such as self-governance, individual liberty, and egalitarianism within the context of their communal structure. The settlers, having recently experienced the trauma of religious persecution and forced displacement, fostered a strong sense of community resilience and solidarity, anchoring their governance principles in the ethos of mutual support and shared responsibility.

Thusly, the memory of their recent exile shaped the colony's approach to governance, fostering a cautious yet resolute attitude toward external threats and reinforcing a commitment to protecting their newfound haven from potential incursions or religious conflicts. This collective experience of displacement and persecution contributed to the development of a strong communal identity and a determined spirit of perseverance within the early days of the colony, serving as the bedrock for the formation of a distinct Presbyterian cultural legacy within the St. Nicholas Colony.

Conflicts with Kiravia

St. Nicholas Colony was attacked by Kiravian naval forces and privateers several times during the Kiro-Burgoignesc Wars, but was never captured or occupied. It was, however, offered as a bargaining chip during peace negotiations to end War of St. Brendan's Strait and ceded to Kiravian control under the terms of the resulting Treaty of Kurst.

In July 1698, Kiravian navy attempted a surprise attack on St. Nicholas Colony's secondary port, Coral Bay. However, the colonial military, prepared for the assault, launched a fierce defense, utilizing coastal artillery and expert marksmanship to repel the Kiravian forces. Despite a prolonged naval bombardment, the defenders effectively thwarted the invasion, but had no maritime ability to molest the enemy to make them withdraw. However, after a two month siege and blockade, the Kiravians grew bored and left. This battle prompted the colony to establish a small naval militia to harass siegeing or invading forces.

In December of 1745, the Kiravians returned and attacked the stronghold of Fort St. Nicholas. Their heavy guns leveled two key western bastions of the fort and this allowed them to land three companies of Marines. They stormed the fort through the ruined bastions but the naval militia arrived and no additional Marines were sent. The battle lasted two days before the Kiravian Marines had expended all of their ammunition and were forced to surrender. The Bergendii sued for peace and randomeo the Marines back to the fleet in return for the withdrawal of the fleet from colonial waters.

Facing a surprise amphibious assault on the unprotected pineapple latifundia of Ananas Grove, which soon became both an invasion and a slave rebellion in 1842 the colonial military swiftly organized a nimble defense, leveraging the dense tropical foliage and the advantage of local knowledge to attack the Kiravian forces and the revolting slaves that had joined their cause. Through a combination of ambush tactics and strategic positioning, the defenders managed to inflict significant casualties upon the enemy, compelling the Kiravian navy and marines to withdraw. A massive public execution of the slaves who had rebelled was held but their were many latifundia owners who sued the colony for recompense and this ended the practice of state-ordained slave executions.

War of St. Brendan's Strait and the lose of the colony...

Economy

The colony was heavily reliant on the cultivation of sugar cane and pineapples, primarily for export. It acted as a vital intermediary trading post between the Martillien colonies of Veraise colony, Credesia colony, and the Bourgondii colony of Equatorial Ostiecia. St. Nicholas Colony was deeply embroiled in the slave trade, utilizing enslaved labor for the cultivation of crops. Under the dominance of the ethnically Bergendii Martilliens, the native population and slaves were subject to harsh, oppressive rule. St. Nicholas Colony's capital and primary port Havre de Grace, served as a critical port for ships to dock for necessary replenishments and repairs, enhancing its strategic importance in the colonial trade network of the era.

The pineapple and sugar cane cultivation economy in St. Nicholas Colony revolved around the establishment of large-scale latifundia-style plantations, owned by Bergendii Martilliens, and worked by slaves imported from all across the Burgoignesc colonial empire. These latifundia, characterized by their extensive land holdings and centralized control, with an emphasis on maximizing productivity and profits, but also with a strong emphasis on health, in particular mosquito and malaria mitigation measures, like those practiced in coastal Dericania.

The pineapple and sugar cane cultivation economy in St. Nicholas Colony flourished, contributing significantly to the colony's economic prosperity and reinforcing its pivotal role in the global trade of tropical commodities during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Governance

The colonial administrator, an appointed ducal viceroy, was tasked with overseeing the implementation of policies and directives established by the General Assembly and other governing bodies. This included ensuring that the laws and regulations were enforced consistently and in accordance with the values and priorities of the colony. These administrators were required to live in St. Nicholas Colony and to be of good standing in the community. When a new ducal viceroy needed to be appointed candidates would put themselves before the General Assembly and petition for a nomination. Those nominated would travel to the Duchy of Bourgondi to be presented to the Duke, who would choose one among them to rule in his stead.

These ducal viceroys were given the title Regal Epistates and they carried out the will of the Duke in the colony. They oversaw the colonial Sergents della Marechaussee, a sort of proto-gendarmerie, to enforce the law, but most importantly they oversaw the Ducal Colonial Customs Officers. These officers enforced the taxation and free flow of goods in, out, and through the ports of the colony. The Regal Epistates also facilitated the development of critical infrastructure within the colony, including the construction of roads, ports, and public facilities. This involved strategic planning, budget allocation, and the coordination of various departments and agencies to ensure the completion of infrastructure projects.

Military presence

The colonial militia and military of the colony initially comprised a small, decentralized force, often consisting of local settlers and mercenaries to protect the interests of the Bergendii Martilliens. As the colony's economic significance grew, so did the need for a more organized defense system. Over time, the colonial militia transformed into a more structured and disciplined entity, trained in both conventional warfare and guerilla tactics to safeguard the colony's interests and suppress potential uprisings among the native and enslaved populations. The military's evolution saw the introduction of more sophisticated weaponry and defensive fortifications to protect the colony from rival Occidental (namely Kiravia) powers and hostile indigenous groups. This shift was accompanied by the imposition of stricter regulations and punitive measures to ensure the compliance of the local population and the enslaved labor force. The military's expansion and consolidation of power mirrored the colony's growing importance as a key trading hub and contributed to the perpetuation of the oppressive colonial regime.

The Battle of Coral Bay, in 1698, exposed the vulnerability of St. Nicholas Colony to naval attacks, emphasizing the necessity for a well-organized and robust colonial naval militia. Following the battle, the initial formation of the naval militia was marked by a chaotic and fragmented process, characterized by internal power struggles and competitive factions vying for influence and control within the nascent naval defense structure.

Initially, the lack of a unified command structure and conflicting visions for the role of the naval militia hindered its effectiveness. Various factions, comprising former privateers, local seafaring communities, and military leaders, operated independently, often leading to confusion and discord within the ranks. However, the continued threat of maritime aggression from rival powers, notably the Kiravian navy, eventually necessitated the collaboration and cooperation of these disparate factions.

Realizing the imperative for a consolidated defense strategy, key leaders within the colony's military hierarchy initiated efforts to bridge the divides and establish a coherent chain of command. Through a series of negotiations, compromises, and joint military exercises, the competitive factions gradually recognized the benefits of unified action and aligned their objectives to safeguard the colony's maritime interests.

Under the guidance of experienced Bergendii Bourgondi naval commanders, brought in from the Duchy of Bourgondi, the militia underwent rigorous training in navigation, naval combat tactics, and the operation of specialized coastal defense vessels. Equipped with a combination of refurbished privateer ships and newly constructed coastal patrol vessels designed in Equatorial Ostiecia, the naval militia exhibited an adept understanding of the region's treacherous waters and utilized their knowledge to effectively intercept and repel any incursions by hostile naval forces.

The naval militia assumed a multifaceted role in safeguarding the colony's maritime interests. Charged with the littoral defense of the colony, the naval militia deployed a network of coastal patrol vessels and lookout stations to monitor and intercept any hostile naval threats, effectively securing the colony's territorial waters and critical ports from potential incursions.

In addition to its primary defensive responsibilities, the militia played a pivotal role in combating piracy in the region. Captains of the militia were given remits to hunt down and neutralizing pirate vessels that posed a threat to colony's trade routes, the militia's swift and decisive actions helped to mitigate the risk of piracy and foster a more secure maritime environment for the colony's commercial activities.

One of its most important roles was to escort and enforce the edicts of the customs agents of the Bourgondii Royal Trading Company, working in tandem to enforce trade regulations, prevent smuggling, and ensure the smooth flow of goods through the colony's ports. Through coordinated efforts and effective communication, the naval militia assisted in the inspection of incoming and outgoing vessels, contributing to the maintenance of a well-regulated and prosperous trade economy within the purview of the colony.

With a focus on swift maneuverability and coastal defense strategies, the naval militia of St. Nicholas Colony played a crucial role in maintaining the colony's maritime sovereignty and securing its position as a key trading hub in the region, contributing significantly to the overall military prowess of the colony for about 115 yrs. After the colony became a colony of the newly unified country of Burgundie it suffered from neglect in general and the naval militia tradition in particular.