Southern slave trade

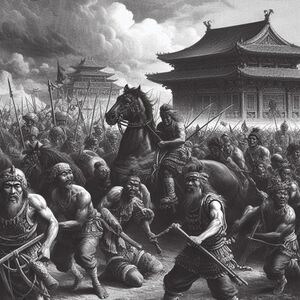

17th century depiction of Qian slavers with captured Polynesians. The face deformities shown are typical of Qian era artwork depicting humans. | |

| Date | 16th to 19th century |

|---|---|

| Duration | Roughly 300 years |

| Location | Audonia, Sarpedon, Crona, Australis |

| Type | Slavery |

| Motive | Profit |

| Organised by | Qian dynasty |

| Casualties | |

| est. 3 million dead from disease and mistreatment | |

| Displaced | 18 million slaves deported to Sarpedon |

The Southern slave trade also called the Cathay slave routes refers to the capture and enslavement of people mainly from the regions of Crona, Peratra and Audonia and their transportation across the vastness of the Ocean of Cathay to Sarpedon. The trade was regulated by the Qian dynasty and the main participants and executors of it were the South Seas Trading Company and other large Daxian slave cartels. The institution of slavery had existed in Daxia and its adjacent territories for centuries; the United Cities had been a state entirely based around the slave trade. But it was not until the territorial campaigns of overseas expansion of the Qian dynasty that slavery got official sanction. Concurrently with this territorial expansion were the first contacts with 'Western' explorers from Sarpedon and the establishment of the Southern route as a viable sea trade corridor to Sarpedon. The Imperium of Caphiria had a prodigious need for slaves that far outstripped the reserves of people susceptible to being enslaved in its imperial periphery. The growing economic relation between both powers based on the aforementioned sea route would feed the slave trade for centuries. The profits from the slave trade would grow to such an enormity that the Qian would start wars of aggression in northern Crona merely to round up more slaves. The operation was not without cost for Daxia, a number of great slave revolts erupted in various parts of the empire, draining the resources of the Qian in costly internal suppression and in lost economic activity. The Great slave revolt of Peratra of 1845 lasted for four years before finally being put down by force, and even then thousands of slaves managed to free themselves.

Not even the outbreak of the Daxian Polynesian Wars would interrupt the flow of slaves to Sarpedon, powerful economic interests on both sides lobbied for immunity for ships carrying slaves from being boarded or hindered. The flow of slaves began to slow down in the late 18th century as sentiment in the Imperium began to sour on slaves of foreign origin; various new policies were enacted that made it easier and cheaper to possess Caphirian-born and educated slaves, even the middle classes had access to Volonian slaves and Slavic servants from the south. As the flow became a trickle, it eventually made less economic sense to export slaves over great distances; internal trading of slaves on the Audonian mainland continued to happen but the margins of profit were far smaller. Growing international distaste for the institution of slavery coupled with the financial collapse of the South Seas Trading Company had the Qian bureaucracy considering moving away from the practice, but this did not happen; slave labor was still in use during the Second Great War and continued to exist until the end of the dynasty; the new republican government under Dai Hanjian finally banned the practice in 1949. The troubled legacy of the southern slave trade and Daxia's role in it continues to cast a dark pall in relations between Daxia and many countries in Crona and elsewhere. Daxian governments have repeatedly refused to issue any apologies or any type of compensation; in their view the matter is only a subject for historians to discuss.

History

Background

Slavery has been practiced in mainland Daxia for thousands of years, early use of slavery is understood to have been reserved for criminals, the average citizen could not be subject to the practice . There are copious archeological records and fragments that point to the widespread keeping of slaves by the elites of the Wa Hegemony and older polities. The fifteen tablets of Wa contain among them a royal edict from king Panshu condemning fourty convicted rapists to lifelong servitude to their victims as castrated slaves. The Xie dynasty first codified the use of slavery in the year 2350 BC during the reign of emperor Heise. This first code contained provisions that allowed local governments to sell prisoners of grave crimes such as murder, sodomy, treason and rape in the slave markets. The Code of Heise also allowed all citizens of the country to freely enslave any barbarians, if they could lay their hands on them and paid a fixed tax for every slave they had, every year. The code also allowed for the enslavement of people who were linguistically very similar to the Daxian people to the point they could be considered branches of one another, namely the Qifu and Tuang peoples were ancient peoples who lived closed to the Xie dynasty heartlands. When the Xie expanded at the expense of these ethnic cousins and their states, there erupted at court great debates about what should be done with the populations. One side argued that as non-Daxians they could be turned into slaves and put to work. The other side countered that being so similar to themselves it would be a great crime to make slaves of them, a crime akin to making a Daxian in good standing a slave himself. On this occasion the latter opinion won out and the Qifu and the Tuang were in the end not enslaved, they do fade from historical record eventually, subsumed into the greater whole of the Daxian nation long before the end of the Xie dynasty.

During the era of strife that began with the fall of the Xie dynasty and its implosion into dozens of statelets fighting for survival, the temporary shattering of Daxian identity into regional ones led to a widening of the use of slavery. To a citizen of the state Hua someone from the state of Zhao was no more Daxian than was a barbarian from beyond the White Waste, even if they looked the same and spoke the same tongue. The attitude varied by states and also over time, for example the state of Cao that would eventually triumph over all others did not enslave other Daxians but instead chose to cajole them into service; this policy decision was of pivotal importance to its eventual triumph as it was able to attract talented people from other states into its ranks without fear of enslavement or humilliation.

By the end of the era of strife and the inauguration of the Shang dynasty, the emperor Cao Kun decreed the restoration of the Code of Heise with several amendments prohibiting the type of excesses seen during the era of strife. The overall number of slaves decreased during the Shang period as internal sources were limited by law and the power of the Degei Confederation waxed; the Shang had no wish to antagonize it needlessly simply to acquire slaves. The one sure entity providing slaves to the Shang was its tributary state of Nasrad, which either bought them or captured them from raids into the Arunid Empire. The Shang dynasty and its scholars held these brown skinned people to be potentially superlative warriors(that they had been captured in the first place was due to Nasrid trickery), the Shang would train them to serve as slave-soldiers. An institution known as the Puren Zhijia, which very roughly translates to the House of the Servants, drilled the slaves in formation fighting as spearmen. The dynasty was interested in lowering its reliance on peasant infantrymen who had to be taken away from their duties as farmers during the harvest season, poor harvests quickly led to instability. If the slaves could take their place on the battlefield, this situation could be easily prevented. In any case the supply of slaves available to the Shang dynasty never reached the levels needed for it to truly replace all of its infantry with trained slaves.

It was the Qian dynasty that began in the 1500's CE that really made the use of slavery a cornerstone of its economic policies. Qian seafaring exploration took them first to the north of Crona and the gates of the Nysdra Sea. The island of Cao had been captured by the predecessors of the Qian, the Zhong, who had left most of the native population in place. The Qian decided to uproot the vast majority, almost eighty percent of the non-Daxian islanders were taken as slaves to be sold in the mainland. Qian pirates and raiders took to capturing slaves from all around the Nysdra south coast and taking them to Cao which became a prominent slave market on its own. The slave trade led to skirmishes with Varshan but their inadequate power at sea ensured these did not escalate into open war, very often the Zurgs were simply paid off to look the other way. The rulers of the Chimoche and Ixa'Taka also routinely engaged in the trade and sold their own 'excess' or troublesome subjects to Daxia, in time the contacts would expand and give the Qian their first foothold in what would eventually become Xisheng. The Daxian colonization of Australis opened new, untapped sources of manual labor. Compared to the strong, centralized states of Crona, the tribe kingdoms of Peratra were technologically backward and not strong enough to resist. The Qian colonies in Peratra became the premier recruitment grounds for slaves. The discovery and establishment of the southern route between Audonia and Sarpedon and regular contacts between the Qian in Peratra and other white 'Easterners' led to an explosion in the number of slaves changing hands. A curious facet of the Qian dynasty's involvement in the slave trade was its policy in regard to slaves afflicted with Dwarfism. Dwarfs who happened to be captured by one of the slaving partners of the empire were usually sold at a premium to government agents and taken to the palace school in Daguo to be educated and serve the dynasty in various capacities; while not exactly free to leave they no longer had the status of slaves. In certain provinces of the empire, officials made it so that not turning over dwarfs to the government was a crime and people caught keeping dwarfs as slaves could be imprisoned for it.

Caphirian connection, inroads into Vallos and zenith of the trade

A relative newcomer to trade with Audonia, the Imperium of Caphiria had deeper pockets than the Carto-Pelaxian Commonwealth and soon eclipsed it in regards to trade with the Qian dynasty. Caphirian need for manual labor was nigh inexhaustible and continental sources were limited to greek and slavic populations of the imperial outskirts. While ordinarily Pelaxians and Cartadanians would have fulfilled the conditions to be enslaved by Caphiria, political expediency and tight economic relations might have meant they were not as readily taken into slavery. Slaves from the domains of the Qian dynasty were plentiful, relatively cheap and ethnically alien to the Caphirian masses, they could be readily dehumanized and exploited as their masters saw fit. The first batch of slaves from the Qian were thirty Muslim eunuchs given as a gift to the banker Ottorio Adelistian Malessar for his good diplomatic offices during the negotiations of 1628. He was given eunuchs so he could not breed them and make more slaves on his own, he would have to buy them from the Qian if he wanted more of the same quality. Soon flesh markets would sprout in disorderly manner all over Zhijun, Truk and Peratra. To firmly control the slave trade, the Qian empowered the nascent South Seas Trading Company to create its own mechanisms of control and taxation on behalf of the dynasty. The Company created the Central Divan of Control to manage the maintainment of standards in the flesh markets, the collection of taxes and duties on sold slaves, the insurance of slave batches and the organization of fleet detachments to provide protection to slave ship convoys. The Company would initially only serve as an administrative agent facilitating the trade but by 1640's it was profiting directly from it, and its control of the central divan made it an unequal competitor that began to dominate the trade. The Qian government was not unaware of this manipulation of its authority to profit but generous bribes were directed at key imperial bureaucrats, and it was seen as preferrable and more practical to deal with a single slaver interest than several.

The South Seas Trading Company employed many gangs of former pirates and bandits to conduct its operations in Peratra. It also hired members of the Kaua tribe, a native group that made slavery its primary activity and who in this manner became a Qian client group. It sourced slaves from Muslim Audonian nations through intermediaries, prominent among these were the Walid brothers who operated in 1660's Tabish. The Walid brothers were high ranking members of the Nasser tribe, one of the largest tribes of the territory that is now southern Rusana. The Nasser tribe were well known for being indiscriminate slavers, they would capture and sell even fellow Muslims. The Nasser tribe was an authority unto itself that could routinely challenge local emirs, their power and connections made them reliable partners in the slave market. Audonian Muslims were seen in Caphiria as capable and obedient breeds, very useful in higher positions such as guards and foremen over other slaves, they were also considered cruel and so even more well suited for keeping their fellow slaves submissive. These suppliers dealt with the Daxians initially in informal ways, deals often agreed upon with a simple handshake. The company introduced contracts that evolved over time and became more stringent and confusing, often with hidden clauses and penalties. Failure to deliver a batch of slaves in the agreed numbers, races and of the specific quality and training could be punished by company officials with punitive fines and seizure of other assets such as buildings and ships; the company often manipulated events in order to force some of its partners to inadvertently breach their contracts and this be able to seize a desired asset. This chicanery enabled the company to extend its tentacles in the principalities of Rusana seamlessly.

In 1728, ambassadors from the South Seas Trading Company approached the Loa Empire to cement an agreement to provide it with slave labor. The empire's economy was heavily reliant on labor intensive sugar plantations and Káámarakatu Raiai'ikaokao was eager to acquire more slaves to maintain production and Kiravian tribute quotas. One particular stipulation of the contract was that no Polynesian slaves be sold to the empire as this would be seen as highly offensive to the Loa people. The empire in turn agreed to pay for the slave shipments with gold coins, ornate rifles and boxes of rare spices. The port city of Aetialo became the most important easternmost port of call to trade and rest for the slaver armadas traveling to Sarpedon. Another important customer was the Kingdom of Isekuende, a subunit of the empire; Isekuende imported mostly Muslim slaves. Of those bought, many thousands died under harsh and brutal conditions but those who survived were eventually assimilated and are today known as the Safa Loa. The slave trade served to increase contacts between Qian Daxia and the Loa in other areas, for example Raiai'ikaokao would acquire Daxian rocket weapons at ludicrous cost and use them to great effect in her territorial conquests and some Loa would migrate to the Daxian controlled island of Truk (these are different from the later waves who migrated during the Takatta civil war, the first are thus known as the Old Loa as opposed to the New Loa). Not all was seamless trade however, there were also isolated violent incidents such as Prince Mog's War during which the Prince Mog waged an unsanctioned war to try and capture the islands of xxx from the Loa. The indirect rule of the Loa Káámarakatu over several of the semi-independent kingdoms sometimes led to misunderstandings or hostility from various Daxian actors.

Slave uprisings and decline of demand

The demand and rationale for slave labor had its peak during the 17th and 18th centuries. Beginning in the 19th century, sociopolitical changes in the Imperium forced a rethinking of slavery and began to give way to a preference for local labor from among the indigeni and peregrini classes rather than relying on foreign chattel. The nations of Vallos were undergoing their own upheavals and in any case the size of their economies was not large enough to compensate from the marked decrease in Caphirian demand for slaves. Concurrently the spread of abolitionist ideas through the world resonated with individuals in bondage, uprisings and violent revolts became increasingly frequent. One such revolt erupted in Cao during the winter of 1831, quickly growing out of control and managing to overtake half of the island before being suppressed. Several uprisings in Xisheng took place with the covert support of Varshan. In 1845 the Great slave revolt of Peratra erupted, led by three brothers, tens of thousands of organized slaves in the countryside attacked their masters in organized fashion and broke free.

End of the slave trade

Participants

Qian dynasty

South Seas Trading Company

Nasser tribal confederation

Carto-Pelaxian Commonwealth

Loa Empire

Routes

The main historic route of the southern slave trade was grimly named as the Road of Flesh. It roughly coincided with the Southern route, it began in the south and east coasts of Daxia, continued on to Daxian Peratra to pick up cargo there and resupply and then headed on east towards Carto-Pelaxian and Caphirian ports in the Kindreds Sea. Slave ships traversing this route would usually make stops along the way in Zhijun, Truk, the Loa Empire and Maristella to pick up provisions and either buy or sell chattel slaves. The main ports in the Kindreds for the reception of slaves were Luvalagelia, Albalitor, Telenea and ____ in Suvera. The Road of Flesh was due to its length, variously considered safe and a death trap for ships due to piracy and fierce sea storms. The western part was routinely patrolled by the Qian navy but the eastern terminus past Truk was seldom so, vessels had to rely on their own armament and traveling in convoys for safety. By the mid 18th century the sharp decline of piracy made the entire voyage much safer, bringing increased profits to the slave cartels.

The second, ancillary route for the flow of slaves was called the Northern Stream, for it collected slaves from Crona and Thervala, turning south alongside the Audonian coast and making stops in Alstin and Metzetta before joining the main outflow from Daxia. This route was sometimes plagued by privateers from Alstin during the 19th century, who sought to disrupt the slave trade after their government had outlawed the practice in its domains.

Effects

Human toll

Diseases

Legacy

See also