Myanga Ayil Khanate

| This article is a stub. You can help IxWiki by expanding it. |

Myanga Ayil Khanate | |

|---|---|

| 1206-1668 | |

|

Banner of the late Khanate | |

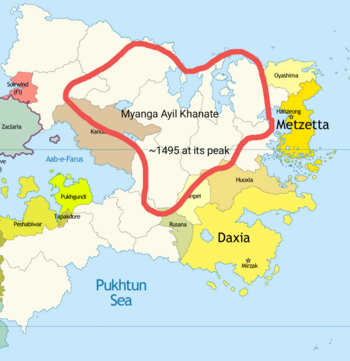

Myanga Ayil Khanate at its peak 1495 | |

| Great Khan | |

| Historical era | Late Medieval Occidental Renaissance Early Modern |

The Myanga Ayil Khanate was a significant empire that thrived in Central Audonia, eastern Al'Qarra and northern Dolong in particular, for over four centuries. It left an ineradicable mark on those region's history, culture, and geopolitics. Founded in 1206, it endured through numerous challenges, only to meet its ultimate demise in 1668 at the hands of the Burgoignesc colonial forces in the Battle of Telmen-Uul.

Founding and Early Khanate

1206-1303 The Myanga Ayil Khanate had its roots in the 13th century, a time marked by shifting power dynamics in central Audonia. In 1206, a charismatic leader named Myanga Ayil united several nomadic tribes under his rule, laying the foundation for the future Khanate. The early years of the Khanate were characterized by both military campaigns and administrative reforms aimed at governing the diverse territories.

Peak Khanate

1303-1495 The 14th and 15th centuries marked the zenith of the Khanate's power. During this period, the Khanate's territory extended across central Audonia, reaching as far as the Capelan Sea in the north and the Aab-e-Farus in the south. It was a time of relative stability, as the Khanate established diplomatic relations with neighboring empires like the Oduniyyad Caliphate and the Zhong dynasty.

The Myanga Ayil Khanate's economy flourished through trade, with the Silk Road playing a pivotal role in connecting the Khanate to the broader world. The capital city, Myangal, became a thriving center of commerce, culture, and learning, attracting scholars, artisans, and merchants from various parts of Audonia.

Economy

The Myanga Ayil Khanate was strategically located along the northern tributaries of the Silk Road. This geographical advantage allowed it to become a vibrant center of commerce. In the late 14th century, the Khans began to mint their own currency, based in the influx of precious metals such as gold and silver. Trade in textiles, spices, precious metals, and luxury goods flourished. Merchants from various parts of Audonia and beyond converged in the Khanate's cities, contributing to its economic prosperity. Major trade hubs became cities, bustling marketplaces and centers of economic activity. Throughout the 14th century the nomadism that characterized all of Myanga Ayil culture became only a portion of society as the hordes of the Khan began to urbanize. A system of regular taxation developed as the power of the Khans expanded and networks of customs officials and tax collectors, loyal to the Khan formalized the ultimate power of the monarch. These taxes funded the expansion of the warband as well as the creation of infrastructure projects, including the construction of roads, bridges, and caravanserais (rest stops for travelers and traders), facilitated further trade and more taxes being collected.

As urbanization occurred there was a need for food and relying on trade alone was not sufficient. In the late 14th and early 15th century the Khanate went through something of an agricultural revolution, and it became a foundational sector of the Khanate's economy. The fertile lands along major rivers were ripe for cultivation. Crops included wheat, barley, rice, millet, and various fruits and vegetables. The cultivation of drought-resistant grains, particularly wheat and barley, was vital to ensure food security. Sophisticated irrigation systems, including qanats (underground canals), were developed to harness water resources for agriculture.

Nomadic pastoralism continued to played a significant role in the Khanate's economy. These pastoralists herded livestock such as horses, camels, cattle, sheep, and goats. Livestock served as a source of food, transportation, and wealth. The Khanate's leaders and elites often possessed large herds of animals, and livestock products like wool, leather, and dairy were valuable commodities.

Urbanization also gave rise a class of craftsmen and artisans, especially in the 15th century. They produced a wide range of goods, including textiles, ceramics, metalwork, and jewelry. Artisans of the Khanate were known for their intricate carpet weaving, tilework, and calligraphy.

Religion and society

In the early 14th century the Khans embraced Islam and throughout the century the religion spread throughout the lands of the Khanate. Sharia law governed the Khanate by the turn of the 15th century. Wealthy individuals, including rulers and merchants, often engaged in philanthropic activities, contributing to the construction of mosques, madrasas, and other public works.

Decline and demise

1495-1668 Despite its earlier successes, the Myanga Ayil Khanate began to face significant challenges in the 16th century. Internal strife, including power struggles among tribal leaders, weakened the Khanate's unity. Economic challenges, including shifts in trade routes and the decline of the Silk Road, as the Oduniyyad Caliphate began to collapse in on itself, contributed to the Khanate's decline. This also destablized the border between the two empires and they were constantly in conflict. The Khanate struggled to adapt to these changing economic dynamics, which included the eventual redirection of trade to Burgoignesc colonial-controlled ports and the loss of revenue. This economic strain contributed to the Khanate's inability to maintain a strong military and administrative apparatus. Additionally, the Khanate's reliance on nomadic pastoralism and agriculture faced environmental challenges. Periodic droughts and changes in climate patterns disrupted food production and lead to scarcity in 1503, and 1513.

The central authority of the Khan weakened, and tribal and regional leaders gained more autonomy. The administrative structure became less cohesive, and the ability to levy taxes and maintain order diminished. Society also felt the effects of these challenges. Economic hardships could lead to social unrest, and tribal rivalries sometimes erupted into violence. The stability and cohesion that had characterized earlier periods of the Khanate's history eroded. As such, the authority of the central Khan was increasingly undermined by powerful tribal chieftains who sought greater power. These internal divisions weakened the Khanate's ability to maintain a unified front in the face of external threats, especially the rise of Occidental colonialism in Audonia, which set the stage for the Khanate's ultimate downfall.

Conflict with the Ularien Trading Company

The conflict that ultimately saw the end of the Khanate started in 1623 when colonial administrators in the Pharisedom of Cote d'Or (modern day Kandara), under the Ularien Trading Company (UTC) met with emissaries of the Khanate. There was immediately tension as both sides demanded tribute from the other and neither side was willing to recognize the traditions of the other. The Ayili emissaries became boastful and rolled out large maps of their realm and spoke of its infinite riches, which only excited the imaginations of the Bergendii colonial administrators. The parlay ended in a stalemate and no formal agreements had been made.

Initial encounters were marked by skirmishes and territorial disputes as both sides vied for control of key trade routes and borderlands. The UTC's colonial forces employed their superior weaponry, to gain an early advantage. Also, fresh off the Great Confessional War they had perfected the Tercio and were particularly adept at fighting the mounted archers of the Khanate with their pike and shot tactics.

As the campaign progressed, the UTC's colonial forces continued to push deeper into the Myanga Ayil Khanate's western territory. They established fortified outposts and trading posts along key routes of the Silk Road. This targeted expansion disrupted trade and strained the Khanate's economy, weakening its ability to resist further advances. In the 1650's colonial forces from the newly founded Far East Colony (modern day Oyashima), began to put pressure on the Khanate from the northeast.

During this period, the Khanate made efforts to seek alliances with neighboring powers, including the Qian, in the hopes of gaining support against the colonial threat. These diplomatic maneuvers, while occasionally providing temporary relief, could not halt the Bergendii's steady advance.

By the late 1650s, the conflict had escalated into a full-scale war. The colonial forces launched a series of major offensives in both the southwest and the northeast, capturing key cities and tightening their grip on the Khanate's territory. The Khanate's leadership faced internal divisions and struggled to mount an effective defense.

Battle of Telmen-Uul

The Battle of Telmen-Uul in 1668 was seminal conflict between the Myanga Ayil Khanate and the combined Burgoignesc colonial forces of the UTC's colonies of Cote d'Or (modern day Kandara) and the Far East Colony (modern day Oyashima), marking the Khanate's final stand against an overwhelming external adversary. This battle unfolded as a culmination of events that had been unfolding for decades, ultimately leading to the Khanate's defeat and the end of its independence.

The Battle of Telmen-Uul took place in the foothills of the Telmen Mountains, a strategically significant region that bordered the Khanate's territory. It was here that the Khanate made its last stand against the Burgoignesc colonial forces. The Khanate's forces, consisted of the shattered remains of the imperial army, a mix of cavalry and infantry, led by the Khan himself, along with myriad irregulars, slaves, and conscripts led by his trusted generals. The Burgoignesc colonial forces at this point were a disciplined, well-organized, well-supplied army equipped with modern muskets, all manner of mobile artillery, and engineers skilled in the rapid development of defensive earthworks. Their numerical superiority and superior firepower gave them a significant advantage. The battle was fierce and protracted. The Khanate's warriors displayed remarkable bravery, employing their traditional tactics and fighting with valor. However, the Burgoignesc forces' firepower proved decisive. Muskets and cannons decimated the Khanate's ranks, and the colonial forces steadily advanced. Despite the Khanate's determination, the battle ended in a crushing defeat. The Khan himself fell in battle, along with many of his generals and soldiers. The Burgoignesc colonial forces emerged victorious, establishing their dominance over the region on July 21, 1668.

In the aftermath of the battle the UTC's administrators did not seek to claim all of the lands of the Khanate, but established a network of spies, agents, and customs agents to ensure that no powerful leader would rise in the power vacuum and that all of the Silk Road trade in northern Dolong was directed through Bergendii customs houses.