Almadaria

This article or section contains future lore that is not canon yet - but someday might be. Stay tuned. |

Almadarian Republic (1846–1875) República Almadariense United Almadarian States (1875–1907) Estados Unidos Almadarienses Almadarian Confederation (1907–1938) Confederación Almadariense Osmian Republic of Almadaria (1938-1963) República Osmiana de Almadaria Federated States of Almadaria (1963-1995) Estados Federados de Almadaria Democratic Republic of Almadaria {1995-2036} República Democrática de Almadaría Valverdian State of Almadaria (2036-204X) Estado valverdiense de Almadaria | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1846-204X | |||||||||

Motto: Por la pluma o la espada ("By pen or by sword") | |||||||||

Anthem: La Guerra que Luchamos Fuertemente | |||||||||

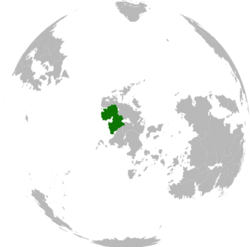

Location of Almadaria (dark green) In Vallos (gray) | |||||||||

| Capital and largest city | Piedratorres | ||||||||

| Official languages | Pelaxian | ||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Almadarian | ||||||||

| Government | Unitary presidential republic (1846-1875; 1995-2036)

(1875-1907) Confederal parliamentary republic with an executive presidency (1907-1938) Semi-unitary presidential republic under a one-party authoritarian personalist dictatorship (1938-1963) Federal presidential republic (1963-1995) Unitary Valverdist one-party state under a totalitarian dictatorship (2036-204X) | ||||||||

| Hernan de Osma (first) Ernesto Allende (last) | |||||||||

| Guillermo de Pardo (first) None (last) | |||||||||

| Vito Sanchez (first) None (last} | |||||||||

| Legislature | National Congress | ||||||||

| Chamber of Councillors | |||||||||

| Chamber of Deputies | |||||||||

| Establishment | |||||||||

• Almadarian Republic | 3 March 1846 | ||||||||

• United States | 16 August 1875 | ||||||||

• Confederation | 1 January 1907 | ||||||||

• Osmian Republic | 13 April 1938 | ||||||||

• Federated States | 6 May 1963 | ||||||||

• Democratic Republic | 14 September 1995 | ||||||||

• Civil war | 2036 | ||||||||

• Central Vallosi War | 2037 | ||||||||

• Fall of Piedratorres | 204X | ||||||||

| Currency | Valverde (ALV) | ||||||||

| Driving side | right | ||||||||

| Internet TLD | .al | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Almadaria, officially the Democratic Republic of Almadaria (Pelaxian: República Democrática de Almadaría) from 1995 until its fall to the Revenant Valverdia Vanguard in 2036, was a sovereign country located in central Vallos, a subcontinent within Sarpedon. It was formed in 1846 at the beginning of the Almadarian War of Independence when it declared independence from the Viceroyalty of Loa Rumas, and lasted until 204X after its defeat and annexation by Castadilla after the Central Vallosi War. It was the second country to have declared independence from the Pelaxian Crown after Vallejar and before Delepasia, and had went through multiple government structures throughout its almost two hundred years of existence.

After the end of the War of Independence in 1846, the first republican government was a unitary presidential republic governed by aristocrat and war leader Hernan de Osma who was primarily opposed by a sizeable faction who wished to organise Almadaria as a more decentralised and federal state, and another faction that believed that the presidential powers were too strong and that it needed to be lessened for fears of a potential dictatorship. Disputes between these three factions would result in a brief state of civil war between the three factions after de Osma's assassination in 1870 which saw the anti-presidential and federalist factions winning in 1875.

The new republican government empowered the position of vice president to an authority similar to that of a head of government despite not necessarily being one as well as empowering the power of the states by delegating certain powers to them. It was much more stable than the preceding centralist republic, mostly due to its stricter adherence to the rule of law as well as the rise in political pluralism. It was soon further decentralised in 1907 after a referendum, with the offices and president and vice president being merged and the new position being dependent upon the confidence of the National Congress. During its time as a confederation, Almadaria was lauded as being one of the most democratic states in Vallos, with some of the subcontinent's most well-known intellectuals having being influenced by some Almadarian ideologies even if indirectly. However, with the onset of the Second Great War, the confederal republic was becoming less and less popular due to fears of a possible invasion by the Delepasians and soon the people called for a stronger central government to be put in place.

The elections of 1938 saw the populist United Almadarians Party winning a supermajority and were thus allowed to pass sweeping reforms which saw the presidency gain independence from legislative confidence, the state being centralised albeit with a certain degree of devolution, and the legislature losing power overall. The new regime, centred heavily around its leader Diego Arnez, was noted for being very dictatorial which had made relations between it and the rest of Vallos, particularly the Delepasian Estadi Social which had seen the new Almadarian regime as a threat to the safety and security and of the subcontinent, and had designated itself as being the rightful heir to de Osma's ideology. The Osmian regime would only last for about twenty-five years before ultimately being overthrown in a popular revolt in 1963 shortly after Arnez's death. The new constitution had restored the old presidential republic, but retained a degree of federalism which wound up contributing to its instability due to numerous disagreements between the states, which in turn made democratisation much slower, before being eventually modified to centralise the state.

The centralisation of Almadaria in 1995 allowed for the country to stabilise and begin to re-democratise in earnest before its turn towards democracy came to an end after the Social Unity Party, which had been the main party that was democratising Almadaria, collapsed due to a series of scandals and corruption charges pertaining to president Pedro Montillo who was subsequently removed from office. This incident largely turn most Almadarians away from liberal democracy and instead support the cultural nationalist and statist Valverdian Popular Front and its presidential candidate for the 2000 elections Arturo Nuñez, allowing for the FPV to win. Under the presidency of Nuñez, Almadaria has experienced a period of democratic backsliding, increasing authoritarianism, and even a rise in an extreme form of Almadarian nationalism which is seen by many international observers as being highly chauvinistic; the Taineans and the Loa minorities have complained about the rise in active discrimination and cultural erasure.

In 2036, Almadaria came under a civil war after Nuñez was overthrown by the Revenant Valverdia Vanguard which soon re-branded itself into the Revenant Valverdia Party under the leadership of Ernesto Allende. The civil war, which was between the PVR and pro-democracy forces, lasted for about a year and resulted in the PVR winning and the pro-democracy forces fleeing to neighbouring Castadilla while Allende's regime began to invade Arona in the name of irredentism which saw the protectorate collapse quickly due to lack of preparedness. An international coalition was formed in response to this invasion, with Castadilla as the main liberating force against Almadaria, thus beginning the Central Vallosi War, the first major conflict in the Vallosi subcontinent since the 19th Century. A subsequent counterattack led by both Castadilla and international forces primarily led by Urcea would establish a provisional Castadillaan government on Almadarian territory before eventually liberating Arona about a week before the fall of Piedratorres to Castadillaan forces in 204X, thus ending Almadaria as an independent country. The provisional Castadillaan government in the former Almadaria would start off as a military occupation being put in place to ensure that any and all forms of armed resistance from remnant PVR forces are eliminated before the military can relinquish control over the newly-acquired territories to civilian administrators appointed by the People's Democratic Party.

Etymology

The name Almadaria originates from a loan word from 9th Century Caphiric observers to describe the region of Vallos that was said to have had a "soul of its own", possibly referring to its incongruity with the rest of the Undecimvirate’s territories and increased combativeness of the vassal kings with one another. Another acceptable speculation suggests that the divided nature of the land, with both indigenous groups and Taineans having been split on either side of the Undecimvirate’s southern borders, created a interminable friction with the vassal kings of the Undecimvirate. Almadaria went on to describe primarily the northern half of the nation, particularly the region that comprised of the Kingdom of Septemontes, though the centuries of cultural diffusion and political interdependence, despite there being no particular demographic diffusion took place, had soon made the southern part of the nation also be referred to as a part of the region of Almadaria. The fall of Almadaria after its defeat in the Central Vallosi War in 204X and the subsequent occupation and integration into Castadilla has largely led to the name Almadaria fall into disuse as a symbol of the former nation's chauvinism.

History

War of independence

After the restoration of the Pelaxian monarchy and the return of the Viceroyalty of Los Rumas in 1814, the recently-restored viceroy was not interested in maintaining the noble titles held by the Cuasilatins of the western provinces, and thus passed a law which forcibly stripped all Cuasilatin aristocrats of their titles by reason of treachery, the sole exception to this law were the Duques who were largely loyal to the Viceroyalty and were eventually forced to flee to the eastern provinces in 1843. Although this was met with great outrage from the former Cuasilatin aristocracy, many of whom had had their titles dating back to the days of the Undecimvirate, it was met with jubilation from the lower classes of the western provinces who were often mistreated by their aristocrats who have abused the fact that they were nobles to assert their authority as well as the Delepasian aristocracy who have largely disliked the Cuasilatin aristocracy for their snobbery and entitlement. The stripping of these titles have, however, led to the aristocracy to embrace their Cuasilatin heritage to distance themselves from the highly-Occidental Delepasians as well as to boycott the viceregal government which in turn led to the viceregal military to attempt to suppress the aristocracy's insubordination. This would culminate in 1846 when the former Cuasilatin aristocracy, in protest to the passage of a new law that would have removed Cuasilatin as a distinct group from the Delepasians, declared the western provinces of the Viceroyalty to be an independent republic. The viceroy responded by launching an attack against the new republic.

In an effort to garner the support of the lower classes, the new republic took on certain elements of Delepasianism, mostly the principles of liberty, popular sovereignty, the rejection of monarchy, and embracing the market economy of capitalism. By ostensibly acting upon the interest of a meritocratic society, the leaders of Almadaria were able to secure much-need popular support in favour of the new republic. The subsequent viceregal interventions were thus able to be repelled quickly and allowed for the republic to enter into negotiations with the viceroy. By securing their independence, Almadaria wished to secure a treaty of non-intervention that would be in effect for a century to allow the new republic to legitimise itself without any further action from the Viceroyalty. Of course, there were some Almadarians who wished to go even further than just a non-intervention treaty; they also wanted to make demands such as taking some of the Viceroyalty that borders Lake Remenau which were ultimately ignored by Hernan de Osma who just wanted to secure Almadarian independence and nothing more and thus the treaty was signed with no amendments.

An intense constitutional convention would follow shortly after the signing of the treaty, primarily being a struggle between the centralists who wished for a strong central government with a powerful executive and the federalists who wished for a more decentralised and federated form of government as well as a third faction that emerged that was largely neutral on centralisation but preferred a bigger emphasis on constitutionalism out of fear that a powerful executive presidency would simply risk turning the nascent republic into a dictatorship. Ultimately, de Osma chose to side with the centralists under the belief that Almadaria was simply not stable enough to handle federalism at this time, and that a powerful executive presidency would serve as a safeguard against the dangers of partisan politics at a time when the republic needs to consolidate and garner further legitimacy. Thanks to de Osma's support, the centralists were able to push through their constitutional principles and pass the first Almadarian constitution, thus officialising the so-called "imperial presidency".

First unitary republic

Styling himself as a national liberal, de Osma passed through various reforms via executive reforms which were met with a lot of controversy from both the federalists and the constitutionalists such as the dissolution of monasteries which especially impacted the new republic's Tainean minority which were highly religious and relied heavily on monastic-based education, the expulsion of the Jesuits which was highly unpopular amongst both aristocrats and lower classes due to the Jesuit's popularity through their humanitarian efforts, and the abolition of the death penalty because a bill that proposed such an idea was about to be defeated by the majority anti-de Osma National Congress. These reforms were largely seen as de Osma overexerting his executive authority to force through unpopular policies that were both anti-clerical and authoritarian. The first decade of the new republic was mostly dominated by constant struggles between the executive and the legislature.

On the tenth anniversary of Almadarian independence in 1856, a rebellion would break out against de Osma led by his own vice president Guillermo de Pardo who had harboured sympathies for the federalists. The rebellion lasted for about five years and the rebels had high support from just about every Almadarian citizen; the only reason why the rebellion was a failure was due to the military's loyalty to de Osma and not to the constitution and thus with their help the rebellions were eventually suppressed. In the aftermath, de Osma embarked on a series of wide-sweeping purges against government ministers and administrators who had supported the federalists or the constitutionalists prior to the rebellion, even replacing his vice president with a more loyal figure. The purge helped consolidate his power over the Almadarian government and put an end to the constant disputes he had to endure, effectively putting the state under an informal rule by decree. With his authority assured, de Osma could finally focus on passing through further reforms without fear of a second rebellion or the legislature strong-arming the executive through sympathetic elements.

These further reforms were passed in an effort to further democratise the republic, to make it so that de Osma could theoretically remain president for life through electoral means and that it would hopefully transfer to his designated successor. During the later years of de Osma's "imperial presidency", some scholars from neighbouring Delepasia have started to speculate if de Osma might be trying to establish a "Western Imperium", a concept that was last seen in Vallos during the Odurian civil war back in the Second Vallosi Warring States period. This speculation, although likely manufactured, did scare neighbouring nations out of the fear that Almadaria was going to attempt to conquer all of Vallos. Indeed, said fear even began to become quite common amongst Almadarians to the point that de Osma was assassinated in 1870 while in Las Joquis after entering his hotel room and getting into a fight with a gunman that had broke in. News of the assassination of the so-called "imperial president" would lead to Almadaria collapsing into a five-year-long civil war between the centralists, the federalists, and the constitutionalists with the latter two factions forming an alliance and defeating the centralists in 1875.

First federal republic

After the end of the civil war had resulted in a federalist-constitutionalist victory, a second constitutional convention was held. Using the 1846 constitution as a template for what not to include, the new constitution delegated a certain yet reasonably high degree of autonomy to the departments while limiting the powers of the president by empowering the vice president; the president still retained a degree of executive power, but now he was forced to share his position of executive with the vice president who was still appointed by the president, but the appointee now had to be approved by the National Congress before he was able to be officially made vice president though his retention remained independent of the legislature. This effectively made the first federal republic a semi-presidential system wherein the legislature enjoyed greater power than they did under de Osma's presidency. The main intent behind this new system was to avoid a repeat of the so-called "imperial presidency" which was increasingly becoming a common term used to refer to de Osma's presidency.

These changes allowed for the republic to stabilise and for partisan political plurality to flourish now that there was no longer a reason for a grand pro-democracy coalition to oppose what was looking to became a grand imperialist coalition which also helped ensure that there was a strict adherence to the rule of law. This also allowed for the republic's economy to enter into a period of consistent yet steady growth as neighbouring countries and the international community began to trade with Almadaria in earnest. The early years of the federalist and constitutionalist republic also coincided with the collapse of the Loa Empire which spurred a small series of expansionism between Almadaria and Delepasia which resulted in the emergence of a territorial dispute between the two countries over which of them held control over the part of the Lake Remenau area that was once a part of the former empire; Almadaria soon also expanded the dispute to the rest of the Lake Remenau area by reviving a dormant claim that was not push in 1846. However, this dispute did not lead to much conflict and both governments largely discouraged their citizens from engaging into conflicts with citizens of the neighbouring country, even sending in a joint military force to further discourage any form of escalation. The dispute was eventually decided in Delepasia's favour in 1904 on the basis that the claim was pretty much dropped when it was not pursued in 1846, thus splitting Lake Remenau between the two nations for the rest of their shared histories.

During the later years of the federal republic, and particularly after the end of the First Great War which Almadaria remained largely neutral throughout, there emerged a new political movement which takes some inspiration from liberal reformists in Delepasia but with certain changes to make it more palatable for Almadarian politics. This movement called for Almadaria to be decentralised even further than the current structure of federalisation according to the 1875 constitution while the offices of the president and the vice president would be merged albeit with some changes in an attempt to circumvent the chance of a particularly authoritarian president. This idea became very popular to the point that the National Congress agreed to hold a referendum in 1907 over whether or not Almadaria should pursue these changes. When the referendum results were finalised, the vast majority of all voting Almadarians had voted in favour of the proposed changes which gave the republic a mandate to begin pass through a series of reforms to bring the proposed form of government into fruition.

Second federal republic

Although historians have called this period in Almadarian history the "second federal republic", it would be more accurate to refer to Almadaria as a confederation as the departments were being given a lot more authority over their internal affairs. This was done because at this time it was considered that because federalism brought sincere democratic institutions to Almadaria, an Almadaria that is further decentralised would be even more democratic, especially as it was seen as a way to minimise the odds of there being an authoritarian presidency to the extent of de Osma's presidency. To further keep the president in line, the offices of president and vice president were merged together and the new presidential office was made to be dependent upon the legislative branch, thus turning the republic into a parliamentary system for the first and only time in Almadarian history, and it was seen as a golden age for the country because of it, and especially in comparison to preceding and subsequent governments as well as its longevity amongst historical periods in modern Almadarian history.

Throughout Almadaria's confederal experiment, the presidency was noted for being at its least authoritarian; being permanently tied to the confidence of the National Congress helped in ensuring that the president simply could not attempt to pass executive orders or even act on his own volition without legislative permission. It was also during this period in Almadarian history that rights for the Tainean and Loa minorities were enshrined for the first time in a Occidental Vallosi nation, very strict laws against hate speech were passed with widespread support, and the right to unionise and women's right to vote were both enshrined constitutional principles; Almadaria was one of the most socially progressive nations at that time, much to the fear of the neighbouring authoritarian conservative Estado Social which had feared that intellectuals might try and take inspiration from Almadaria. These fears were, however, largely unfounded as most Delepasian intellectuals have generally sided with the regime in the name of preserving their reputation and livelihoods.

Almadaria's reputation for being a torchbearer of democracy at this time was mostly due to it having remained a democracy at a time when both fascism and corporatist ultranationalism was on the rise in Sarpedon, particularly in Delepasia with the beginning of the Estado Social in 1924 as well as in Lucrecia when fascist rule began in earnest in 1923, but even then its reputation mostly came long after the end of the era of confederal government. The rise of the authoritarian, populist, and syncretic nationalist United Almadarians Party (PUA), led by Diego Arnez, happened after the beginning of the Second Great War as faith in democracy, although not necessarily shattered, had lessened due to fears of a possible Almadarian entry into the war; to most citizens the confederal system was seen as very vulnerable to invading armies, but they were willing to overlook it during peacetime. During wartime, however, this seemingly inherent flaw was becoming more and more obvious to the point that in the 1938 elections, the vast majority of previously-safe seats for the establishment parties had elected PUA members who in turn elected Arnez to become the new president.

Social-nationalist era

The new government wasted no time in passing a series of sweeping reforms which were designed to centralise both the nation as well as the executive. These changes were to align the government with a new ideology known as Osmianism. Developed in the early 1930s, Osmianism called for a populist and nationalist Almadaria in which executive power is consolidated in the person of the President, and specifically Diego Arnez himself, as well as centralising the structure of government, though as a compromise the departments were accorded a certain amount of devolution from the central government. Democracy was retained to an extent, though mostly in the form of an advisory poll in which it is the turnout that determines whether or not the results of the poll must be followed. High turnouts indicated that the proposed decision that the poll was made for was very popular, and low turnouts indicated that the proposed decision that the poll was made for was very unpopular; these polls were instrumental in securing a degree of accountability for the Osmian regime. Economic nationalism was also a major component in Osmianism, believing that an economy that is reliant on foreign firms would put the nation under control of said foreign firms.

Osmianism was a rather pragmatic ideology for the most part. It saw itself as more of a big-tent Almadarian nationalist movement which welcomed anyone who were in favour of a strong and sovereign Almadarian state regardless of their ideological beliefs; this meant that the PUA not only permitted integralists, corporatists, and traditionalist conservatives into the party, but also social democrats, socialists, and Marxists as well. This broad church approach towards politics was one of the main reasons why the Osmian regime, and the Arnez presidency overall, was about to hold onto power; with practically all Almadarian political ideologies being represented in the PUA, there was no single ideological group that was considered to be ineligible for possible membership in the PUA. It also helped in minimising the potential risks of revolts since most of the main leaders of each of the primary ideological groups in the country were members of the party, often with the more influential figures holding high-ranking positions in the government.

The biggest and no doubt most fatal flaw of the Osmian regime was that it was structured as an authoritarian personalist dictatorship. In most dictatorial regimes, the governing institutions are typically organised in such a way that they may continue to function normally even after the current dictator passes away and even in a scenario in which there are no successors. The Osmian regime, on the other hand, was organised in a manner that it could only survive so long as Diego Arnez lived; should he pass away there would be no one who could be deemed a proper successor of Arnez as almost all members of PUA were highly ideological and had only joined the party so as to gain and maintain influence. Indeed, when Arnez passed away in 1963 after getting struck by lightning. His successor was largely uncharismatic and rather disinterested in maintaining the broad church approach that Arnez had adhered to. This meant that the more ideologically-minded officials began to leave the party to instead establish their own political groups. The rapid decline in party membership also led to people becoming more and more dissatisfied with the regime, and by mid-1963 a coalition of pro-democracy advocates would revolt against and overthrow the Osmian regime.

Third federal republic

The fall of the Osmian regime and the subsequent restoration of democracy would see the new government begin yet another constitutional convention. Learning from the perceived mistakes and weaknesses of the last two attempts at federalism, the draft for the 1963 constitution gave the new government much more powers and oversight than what was granted to the governments of the previous two federalist experiments. The draft also preserved the presidential system, but this time with some added checks and balances in an attempt to prevent further authoritarian measures from happening in the future. This new constitution was approved and was soon effective in 1964. Another major aspect of the constitution was that it was intended to essentially be a clean start for the republic, divorcing itself from the legacy of the previous constitutions and governments as well as to symbolise Almadaria's democratic rebirth after over a century of what was seen as a glorified back-and-forth between democratisation and democratic backsliding.

Because of the twenty-five years of being under the rule of a personalist dictatorship, the new constitution provided for the establishment of a committee to handle the re-democratisation of Almadaria through a process known as a "democratic tutelage" in which the people were to be taught about the democratic processes and the constitutional values of the rule of law. This period was slated to last for about a decade or two assuming that things were able to go smoothly without any issues. It was divided into three phases. The first phase was to educate the people on the legal system and the constitutional rule of law; this was to show that all citizens were equal before the law and there was to be no inherent distinction between individual citizens. The second phase was to educate the people on the structure of government; living in a federation, the citizens were to be taught that the departments had certain rights that the federal government could not unilaterally take away and that each levels of local government had their own administration. The third phase was to educate the people on the democratic process; all citizens age 18 and above were entitled to the right to vote regardless of gender, race, or religion, and they were also taught about the nation's electoral processes.

In theory, this period of "democratic tutelage" seemed like Almadaria was finally about to become a sincere constitutional republic once again. In practice, however, the departments were largely insubordinate and instead had their representatives engaging in very long filibusters which no only prevented the "democratic tutelage" period from working as planned it also tacked on additional phases which were ostensibly added in to make sure that all citizens were fully-educated in Almadarian civics, but in truth were merely long-winded history lessons and exceptionally difficult exams that made proceeding to the other phases very difficult if not outright impossible. The filibusters and constant lengthening of the "democratic tutelage" also ensured that there would be no more elections during the third federalist period as one of the requirements for holding a fresh election was for the tutelage period to be completed. As a result, Almadaria had no clean general elections in over fifty years thanks to the Osmian regime and the constant obstructionist efforts of the departments.

Second unitary republic

The provisional president of the third federalist republic, Raul Hernandez, having had enough of the constant stalling in the hands of the departments, consulted the justices of the First Court and was advised to pass an executive order with them guaranteeing that they would uphold it if it were to be question. Thus, in 1995, the third federalist republic was dissolved by executive order which made way for a new constitutional convention which made great use of the 1963 constitution, but this time the 1995 constitution would greatly centralise the government and put an end to the federalist experiment just so the republic could finally focus on the process of re-democratisation. Provisional president Hernandez would step down shortly afterward and the subsequent election would see the pro-democracy and christian democratic Social Unity Party (PUS), led by Pedro Montillo, winning a majority in the National Congress. Upon his inauguration, President Montillo began to seriously pursue the process of re-democratisation, but this time without the complex period of tutelages nor the fear of constant filibustering from the departments.

During the early years of the Montillo presidency, domestic support for the full and complete re-democratisation of Almadaria was at an all-time high with more people becoming politically-engaged and more active in the political sphere. Polls conducted during this "democratic honeymoon" period have indicated a sharp growth towards political pluralism and support for an Almadarian liberal democracy. Relations between Almadaria and the rest of Vallos also began to greatly improve, with the republic beginning the process of applying for a membership in the Vallosi Economic Association and a request for observation status until the membership process was completed and approved by all member states (Castadilla, Lucrecia, and Takatta Loa). By the year 1997, it was looking as if Almadaria was about to enter into the modern age as one of the subcontinent's finest democracies, and early polling indicators for the 2000 elections were predicting an electoral landslide for all pro-democracy parties, with Montillo's PUS being expected to win a supermajority.

The "democratic honeymoon" period would not last, however, as in 1998 President Montillo found himself embroiled in a massive corruption scandal with numerous bribes, some even dating back to the 1970s, being revealed. To make matters worse, several prominent PUS politicians were indicted for their role as being particularly brutal law enforcement agents during the latter years of the Osmian regime. These scandals, combined with the revelation that the PUS had its own slush fund, had contributed to not only the collapse of the PUS, but also a sudden reversal in public opinion towards re-democratisation in general. With fears that a liberal democracy would only further encourage additional corruption and scandals, many Almadarians began to seek alternative parties that were not so committed to re-democratisation, but were largely free of any significant scandals or corruption. Most would wind up supporting the Valverdian Popular Front (FPV) led by Arturo Nuñez for the 2000 elections.

Democratic backsliding

The 2000 elections in Almadaria were punctuated by the electoral victory of the Valverdian Popular Front in the legislative and the FPV candidate Arturo Nuñez in the presidential elections. Since his inauguration, President Nuñez had initially cultivated an image of being a "liberal nationalist" mostly to appease the remaining FPV members who adhered to the party's original liberal stances as well as to provide a sense of continuity between himself and Almadaria's first president Hernan de Osma. Much of his work during his first term was dedicated to tackling corruption which was one of his major campaign promises after the fall of PUS due to constant scandals in 1998, and to portray himself as a "law and order" leader whose stances align predominately with most Almadarians who wished for a president who was "tough on crime". Indeed, tougher sentencing and harsher punishments started to become more common in the Almadarian court system as focus started to trend towards punitive justice and away from rehabilitative justice, with Nuñez himself referring to the latter form of justice as being "highly misinformed; allows criminals to be let off with nothing more than a slap on the wrist".

Nuñez and FPV won the 2005 elections with a landslide supermajority. Emboldened by this huge electoral mandate, he began to distance himself and the FPV away from its liberal roots with most pre-Nuñez members being purged. Instead, the FPV would begin to embrace more socially conservative policies, with the president and his party beginning to replace most of the justices of Almadaria with FPV loyalists who would not only serve to act as a bastion of conservatism, but also to secure Nuñez's rule over Almadaria. The Nuñez also started to promote a highly statist form of Almadarian cultural nationalism, with much of the legal protections placed for the Loa and Taineans being slowly eroded away through justices striking down certain aspects of those protections. The FPV also passed a constitutional amendment which saw the Catholic Church be raised to a favoured position despite Almadaria officially remaining as a secular state during Nuñez's second term.

Through the establishment of a political machinery which made sure that anyone who delegated their votes to their administrator would have their votes counted as votes for Nuñez and the FPV, the president and his party were able to safely win not just a third term, but also a fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth term. During these next few terms, the trend of Almadaria's democratic backsliding was becoming more and more apparent as the FPV-controlled legislature began to bar certain opposition parties from being able to win representation in the National Congress if they have consistently opposed the Nuñez presidency; opposition parties which have consistently supporter the Nuñez presidency were instead given the privilege of being able to win representation in the National Congress which ensured a permanent FPV government for as long as the party existed. Further breakdown on the separation of church and state would see Catholicism become the state religion of Almadaria for the first time since before Almadaria became independent.

Almadarian Civil War

In 2036, after a period of mounting tensions between Almadaria and Castadilla, an ultranationalist terror group by the name of Revenant Valverdia Vanguard would emerge and begin coordinating a series of terror attacks across Almadaria. The Revenant Valverdia Vanguard (VVR) was first established in the mid-1970s as a pseudohistorical society which promoted the concept of Valverdism which claims that Almadaria was the successor state to the supposed Valverdian Empire, a claim which many accredited historians have debunked because the map used to claim the supposed existence of Valverdia was in fact a partial map of the Undecimvirate, particularly in western Vallos. Valverdism would soon evolve from a pseudohistorical concept to a syncretic political ideology which promoted a particularly extreme form of ultranationalism that called for a so-called "Valverdian cultural renaissance" while promoting a form of Almadarian irredentism that claims land from all of Arona, half of Castadilla, and parts of Takatta Loa. Other policies that the VVR supported included state atheism, mainly under the belief that organised religion was a distraction, as well as an extreme form of racial prejudice against Taineans and the Loa. All Vallosi people of Occidental ancestry were allowed to join unless they were Castadillaan citizens; Taineans and Loa were formally barred from joining.

These terror attacks were highly effective in destabilising the Nuñez presidency and soon the VVR was able to launch a coup d'état against the republic, a coup that enjoyed widespread popularity amongst the Almadarians as they had gotten tired of Nuñez's seeming incapability in waging war against Castadilla. With the Nuñez presidency overthrown and collapsed almost immediately after being removed from power, the only remaining group that stood in opposition to the VVR, which by then had rebranded itself as the Revenant Valverdia Party (PVR), was the independent opposition which had formed an alliance and moved to the south of Almadaria where it established a democratic opposition government before receiving recognition as the legitimate Almadarian government. The two governments would soon enter into a state of civil war against one another, with the democratic government initially making some gains due to the PVR's lack of preparedness, but when PVR forces started to get reinforcements from amongst the citizenry of Almadaria the tide of war would soon turn against the democratic opposition with the latter faction losing in early 2037.

To avoid possible capture and execution, the leadership of the Almadarian democratic opposition, alongside a few remaining units that did not fall to the PVR government, would flee to neighbouring Castadilla where they were permitted to set up a democratic government-in-exile. The government-in-exile was largely short-lived, however, and its governing council would wind up voting to integrate the Almadarian democratic opposition into the Castadillaan government, effectively uniting Almadaria with Castadilla and giving the latter country a legal claim over the lands of the former republic which was recognised as lawful by the League of Nations after it was verified that the council's vote to unite the exiled government with Castadilla was done fairly and without coercion; all former pro-democracy parties would merge with their Castadillaan counterparts, and Almadaria would cease to exist as an internationally-recognised sovereign nation while the PVR regime was declared by the League of Nations to be an unlawful rogue state and thus was kept under close watch by its neighbours just in case it tried to invade any of them.

Central Vallosi War

Although its neighbours were expecting the PVR government to attack any of them at one point, they did not expect them to launch an invasion of Arona so soon after their victory in the civil war. As part of their goal to restore the supposed borders of the pseudohistorical Valverdian Empire, the PVR government decided to attack Arona mostly due to its size and to wipe out the only independent Tainean nation state which it saw as a potential threat to its existence mostly due to the belief that it would somehow attempt to make the state's Tainean minority more insubordinate. The invasion was surprisingly fast thanks to the use of fast guerilla tactics to disable the Aronese nation's communication systems at the border followed by a campaign of lightning warfare. Not only did these two tactics work well against Arona they also ensured that it would fall relatively quickly, placing the Tainean nation under total occupation by the PVR government. This caused a huge refugee crisis as the Aronese Taineans fled to Equatorial Ostiecia, Vespera, or Castadilla for protection from possible persecution if not outright ethnic cleansing in the hands of the PVR.

The international response to the PVR government's invasion and conquest of Arona was almost immediate with Urcea, Arona's protector, assembling an international coalition against the PVR government with Castadilla as the coalition's main Vallosi leader. The coalition's first move was to perform a counterattack against the PVR's forces in Arona, with Castadilla invading the former Almadarian territory through the Astol Plains. The counterattack was slow at first due to constant attacks from the PVR government's so-called "vigilante forces", or Almadarian citizens who have taken up arms in support of the PVR, but these forces were easily defeated when coming up against the coalition forces and thus began to largely die down once Castadilla began to establish an occupation zone on former Almadarian territory; the Castadillaan government would then declare the occupation zone to be a provisional western Castadillaan sub-national government subject to further development once the counterattack is over. Eventually, Castadillaan forces would reach into Aronese territory where it would meet allied Urcean ground forces as they liberated the country from the PVR government's control. With the restoration of Arona after its liberation, direct Urcean participation in the conflict would finally end, but Urcean forces would remain in Arona to prevent a possible attempted second invasion.

With Arona liberated, Castadilla would finally begin to focus on its ultimate goal, conquering the former territories of Almadaria. By this point in the conflict, the primary motivation behind Castadilla's attacks was no longer to liberate Arona now that it had been liberated, but rather it became a mission to destroy Almadarian chauvinism once and for all, believing that if Almadaria were to be kept as an independent nation it would only attempt additional invasions in the future. Thus, to Castadilla if the Almadarians were to be trusted to enter into civilised society once more, then the very idea of Almadaria as well as an Almadarian culture would need to be completely deconstructed and removed altogether. It would not be until 204X when the PVR government would finally fall shortly before Castadillaan forces arrived in Piedratorres. With the conquest of Almadaria completed, the Castadillaan government would embark on a period of military occupation to pacify the region and eliminate any remaining PVR-affiliated cells. Once the former Almadarian lands are considered pacified, then the military will relinquish control over the former Almadarian territories to make way for a civilian administration governed by People's Democratic Party officials under which the former Almadarians will see their national identity and culture deconstructed and replaced with regional identities within the Castadillaan culture before they can be taught how the Castadillaan democratic system works before the new territories can be admitted as states under constitutional government.

Government and Politics

Almadaria was a unitary presidential republic, having sourced much of its constitutional principles as well as general framework from the venerable legacy of participatory government in Cartadania. The nation's first constitution, which was fully ratified in 1847, much like the current 1995 Almadarian constitution, outlined three branches of government as per the principle of separation of powers as well as a system of checks and balances. Subsequent constitutions between the 1846 and 1995 constitutions have experimented with both decentralisation and oftentimes even taking power away from the presidency with the sole exception being the highly centralised and dictatorial "Osmian system" which governed Almadaria from 1938 until 1963.

The Almadarian government was once touted and lauded as the first successful sovereign democracy in Vallos, having had strong democratic traditions and rule of law from its establishment in 1846 until 1938 when Almadarian democracy was largely dismantled in favour of a personalist dictatorship with the rise of the United Almadarians Party under Diego Arnez. Democracy would only be restored shortly after the death of Arnez in 1963 and his government was overthrown in a popular revolt; the new federal republic's attempts at re-democratisation was largely stifled by endless disagreements between the states and thus in 1995 federalism would be abolished. Almadaria's process of re-democratisation would be stifled again after the fall of the Social Unity Party and the rise of the Valverdian Popular Front in 2000.

Almadaria was known for its distinct constitutionally-enshrined election process, commonly known as "rat cage elections", which pitted all candidates against one another in a highly competitive primary election, regardless of party affiliation. Generally, the top four candidates were selected to move on to a secondary election. This nonpartisan election process had kept any one party from gaining superiority over one another, but when Arturo Nuñez was first elected president in 2000 this process was changed so that only the top two candidates would be able to go on to a secondary election, and had instituted an electoral machine in which people who opt to let their administrators to vote on their behalf will be counted as votes for himself. This ensured that he would comfortably win subsequent presidential elections without moving to far from the constitutional principles of Almadaria, thus turning a system that was designed to diversify and increase representation of otherwise marginalized groups into a system that would guarantee his reelection ad infinitum.

Executive

According to the 1995 constitution, the presidency was established as the head of the executive branch of the Almadarian government. The President of Almadaria was to be elected by popular vote, and selected who may serve as their Vice President and cabinet members upon their electoral victory. One of the cabinet ministries, the Ministry of Justice which was responsible for both national law enforcement and legal administration, was headed by the Attorney General and initially answered to the First Court of Almadaria as their executive representative in presidential affairs. The executive branch existed in a state of dual legitimacy with the legislative branch, both contained democratic features and abilities to shape policies. The 1995 constitution added additional checks and balances that were supposed to make the President be less independent of the National Congress such as limiting his veto power by adding method for the National Congress to override the veto, make the President form a collaborative relationship with the President of the Chamber of Deputies, and other measures which would have kept major divisions from happening within the government. Nonetheless, the President still held sole responsibility for forming his cabinet and was still allowed to sign executive orders.

Since the year 2000 and the rise of Nuñez and prior to the civil war, the powers of the President had increased in many different ways such as taking advantage of his legislative supermajority to remove most of the First Court justices and replacing them with loyalists, passing executive orders to bypass obligations to cooperate with the National Congress, install an electoral machinery to perpetuate his rule in subsequent elections, reduce the remaining vestiges of devolved regional power, and subvert the term limit by pushing through an amendment.

The Cabinet of Almadaria was made up of nine ministries, whose heads were selected, and were not subject to the approval of the National Congress, by the President. The cabinet ministries and their senior officials served not only as administrators of their respective subbranches of the executive branch, but also in an advisory role to the President and Vice President in implementing policy. Formerly subject to frequent government restructuring, the members of the Cabinet as of 2000 were: the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Trade, the Ministry of Environmental and Resource Concerns, the Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of Science and Technology, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, the Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of Education, and the Ministry of the Interior.

Legislative

The National Congress of Almadaria was the bicameral legislative body of Almadaria. The two chambers of the National Congress were the Chamber of Deputies, serving as the lower house, and the Chamber of Councillors, serving as the upper house. Elections for both houses were held at different intervals, with the 100-member Chamber of Councillors holding an election once every seven years, and the 600-member Chamber of Deputies holding an election once every five years; Councillors were elected by lower-level regional administrators and even Deputies through indirect elections, and the Deputies were directly elected in a two-round system of primaries. The fact that Councillors held their seats for seven years have often meant that the composition of the Chamber of Councillors may conflict with the composition of the Chamber of Deputies. This would often have resulted in bitter disagreements between both legislative houses prior to the Nuñez presidency.

Both chambers were presided over by their own presidents, both President of the Chamber of Deputies as well as the President of the Chamber of Councillors who were elected by members of their respective legislative bodies. Their purposes were to oversee their chambers and manage the numerous agencies that were interlinked with each legislative house. The presidencies of both chambers were not term-limited so long as they maintained the confidence of their respective chambers. This also meant that they were often the officers who introduce bills to their respective chambers before opening the floor up for debates and eventual voting.

Ever since the beginning of the Nuñez presidency in 2000 yet prior to the civil war, the National Congress had underwent a series of executive orders which made sure that not only would it remain in a subservient role in regards to its relationship with the presidency, but it was also rigged to ensure that the FPV would maintain a perpetual supermajority through taking advantage of non-voters and preventing prominent independent opposition members from being able to maintain their candidacies by manufacturing last-minute rules that removed them from the ballot so as to circumvent accusations of suppressing the opposition.

Judicial

Almadaria's judicial branch, according to the 1995 constitution, were made up of institutions that were present at each level of government. The highest court in the nation was the First Court of Almadaria which had jurisdiction on criminal matters, civil cases, the constitutionality of certain policies, administrative law, and even self-regulation. All justices of the First Court were nominated by the President and were subject to the approval of both houses of the National Congress. Justices that were approved generally stay on their positions for life except in cases when they were removed from power or decided to retire. The former case was used extensively during the early years of the Nuñez presidency as numerous justices were removed and replaced by justices who were aligned with the FPV thus ensuring that the FPV would be able to get their laws passed and upheld with little difficulty.

Federal subdivisions

Almadaria's primary subdivision was the departments, of which there were twelve of them, and one autonomous district which held the nation's capital. One the second level, the departments were divided into provinces, each led by prefectos ("prefects"). Lower levels of government divided the provinces into numerous municipal districts. The 1995 constitution gave less-populated municipalities the option to join up with larger municipalities to consolidate resources for more effective distribution, often resulting in the oft-quoted criticism Uno freno; doce caballos ("one bit; twelve horses"). All levels of government had their own governing authorities, each with their own leaders such as prefects for provinces, and alcaldes ("mayors") for municipalities. However, local government authorities do not have their own legislatures, instead most of their administrators were directly-elected.

The twelve departments of Almadaria, from north to south, are as follows:

- Lacusentia

- Portana

- Avevalles

- Septemontes

- Natsolea

- Interumina

- Astolia

- Mortures

- Yarrambo

- Mujulaste

- Rangiura

- Tainea

Politics

Ostensibly a multi-party system, Almadarian politics since the year 2000 were under the rule of the Valverdian Popular Front (FPV). Founded in 1995, the FPV was initially a liberal opposition party to the more popular christian democratic Social Unity Party, but when Arturo Nuñez was made leader of the FPV he began to turn the party away from its liberal roots and more heavily towards conservative statist cultural nationalism mixed in with populist rhetoric and overall hostility towards liberal democracy. Opposition parties since the beginning of the Nuñez presidency were divided into two groups, those being the official opposition, and the independent opposition. Official opposition parties were parties that often allied themselves with the FPV, and those included the Almadarian National Union (UNA), the Liberal Party of Almadaria (PLA), and the Democratic Liberties Alliance (ALD); these parties were largely a part of the political right and have held ultranationalist sympathies. The independent opposition referred to parties that were opposed to the FPV and were often suppressed or banned from participating in politics, and those included the Civic National Party, Congress of Freedom, and Justice and Development; these parties varied in ideology, but were opposed to the ultranationalism of the FPV and the official opposition parties.

Prior to the Almadarian Civil War, the FPV held the vast majority of positions in all three branches of government, effectively making the nation a dominant-party dictatorship with a controlled group of parties that served as the official opposition yet were effectively puppets of the FPV. Independent opposition parties had very little representation and when they did the winning candidate often referred to themselves as independent so as to ensure their political survival while doing everything they could to try and stop the Nuñez regime. All of Almadaria's political parties have either been dissolved, banned, or merged with their Castadillaan counterparts by the time the nation was annexed by Castadilla in 204X.

See also

- Grey Map of Almadaria, a common symbol of Almadarian irredentism

- West Vallos Districts, referring to the Castadillaan military occupation of the former Almadarian lands

- Almadarian vigilantes, Almadarian citizens serving as an unofficial military force