Government of Urcea

The Government of the Apostolic Kingdom of Urcea is a type of dual federalist hierarchy and dual-sovereignty system. The Urcean Government is organized through a system of documents, edicts, and precedents called the Constitution of Urcea, which was largely formed through the twin ideological impulses of Catholic social teaching and Crown Liberalism. Urcea's form of government, as well as its Constitution, developed over a period of more than a millennia.

At all levels of state, the Apostolic King-Elector is the central organizing Constitutional basis for authority, and all who live in the Kingdom are legally understood to be “subjects”, rather than “citizens”, though the concept applies equally and the terminology is used interchangeably. The King is constrained by a series of written and unwritten constitutional precedents. The system can best be described as something of a constitutional monarchy with a semi-presidential system below the Crown.

The country employs a type of fusion legal system that has been trending more towards the side of common law since the turn of the 20th century; Royal Proclamations, Decrees, Bulls and canon law as interpreted by Royal courts form the basis of a majority of historical statute in the Kingdom, but the primary legislation in the country is determined by the Conshilía Daoni, which is the national legislature. Local governments, provinces, and the semi-autonomous regions have home rule ability to pass their own legislation, which forms the remainder of the body of statutes within the country. Existing somewhere between these is the rule making authority of the various Royal ministries, part of the Conshilía Purpháidhe, who not only issue their own rules and regulations but ensure a uniform legal-economic system throughout the country. The Conshilía Purpháidhe, which serves as a quasi-executive ministry, is chaired and directed by the nationally elected Procurator, whose office has its origins in the Royal Steward.

The Conshilía Daoni serves as the lower house and primary body of the national legislature, and it is variously controlled by organized national political parties which exist and contest elections that occur throughout the country, including local and provincial elections. The Conshilía Purpháidhe, serves as the executive ministry and is appointed by the Chancellor and Temporary President, the majority leader of the Daoni. There also exists a separate chamber sometimes called an upper house, called the Gildertach, which represents Urcea's guilds and holds limited authority and can legislate primarily on trade but also on various regulations for the guilds.

Legal Structure of the Kingdom

The Apostolic King of Urcea serves as Head of State and is the unifying legal basis for the country as a whole and the National Government in particular. Legally speaking, the provinces owe their allegiance to him as King, as the provinces are constituent parts of the Kingdom itself. The King rules in the crownlands according to their individual tradition and precedents; in the Urceopolis he rules as Archduke, in Harren as Grand Duke, in Canaery as Prince-Elector, and the autonomous states as Prince-Sovereign, though in practical terms and common parlance he is hailed as Apostolic King in all his realms. The Apostolic Kingdom, however, is not a confederate collection of holdings; many legal and administrative reforms implemented since the end of the 16th century has gradually integrated all of the Apostolic King's holdings into a single legal federal polity, which allows the Royal Courts jurisdiction over the entirety of the realm and the authority of the two Concilium to extend over the entire country.

The Apostolic Kingdom is said to have a "dual-sovereignty" system, because the Apostolic King of Urcea is sovereign and is the central Constitutional organ by which the state functions, but the Conshilía Daoni is sovereign insofar at is an expression of the people of Urcea and functionally holds supreme lawmaking authority within the Kingdom. Some observers have noted that the strength of Urcea's federalist system provides that the Kingdom should actually be referred to as "triple-sovereign", given the relationship between the federal and provincial governments. In this context, the Apostolic Kingdom is often referred to in some contexts as a "federal union", best summarized by P.G.W. Gelema as "the union...of the whole people with the Apostolic King, bonded to each other through the provinces which themselves are bound to the Kingdom in perpetual allegiance to both the Kingdom as legal entity and to the King as a man."

In terms of legal theory, the Kingdom is considered to be subject to the Holy Levantine Empire by the merit of that institution being coterminous in the person of the Apostolic King himself. Due to the position of the Apostolic King within the Constitution, his personal role as Emperor of the Levantines would potentially require the Urcean government's laws and statutes to be secondary to that of the Imperial Diet, the terms of the Treaty of Corcra left the dictates of the Diet non-enforceable. Additionally, the Diet has not met since the early 1930s and was functionally dissolved with the Treaty of Corcra, making the distinction of Urcea's participation within the Empire purely nominal. The primary legacy of this participation is the nomenclature of the nation's army and titles of the Apostolic King; the Royal and Imperial Army reflects the King's status as Emperor of the Levantines.

Executive Branch

The Urcean executive branch is legally and nominally led by the Apostolic King, who serves as Chief Executive and Head of State. Under the terms of the Constitution of Urcea, his powers are not that of Absolute Monarch and the constitutional tradition will limit his direct interference in the day-to-day affairs of the national government in addition to the affairs of subsidiary and local governments. The King wields a considerable amount of political influence and can constitutionally arbitrate deadlocks between the Procurator and Conshilía Purpháidhe, giving the King a major role in the governance of the Kingdom at various points. The King, critically, has the authority to declare war, though his declarations must be ratified by the Conshilía Daoni by a majority vote. According to case law, the position of Apostolic King is not a public office but rather an "indelible quality" of the man seated on the Julian Throne.

In addition to the power of the King to settle disputes between the Procurator and the Conshilía Purpháidhe, the King has several other domestic powers based on his own prerogative. The most commonly used power is that of appointment; all of the officers of the Armed Forces are appointed by the King himself, usually through his Household Office for Commissions, and the King also selects some members of the Urcean judiciary through the appropriate Household Office. Most importantly, the King nominates a list of candidates for Censor to be narrowed down by the Urcean Conference of Catholic Bishops. The King also, on consultation with the Procurator, appoints Governors-General of the royal holds and Rectors of overseas territories. The King also has the power, in the event of budget impasses between the Procurator and the Daoni, to unilaterally extend Royal budgets in order to prevent Government shutdowns. The King's Budgets cannot substantially alter the previous year's budget being extended, but he can change the funding amount in any line by five percent in either direction, giving the King's Budgets flexibility in the event of recessions and severe shortfalls. The King has a very exclusive veto authority, restricted entirely to bills in which both Censors have issued a formal objection to.

Within the executive branch, the King enacts laws and policies upon the advice of the Procurator. The Procurator, who is directly elected by the nation at large following a national party primary system, serves in many ways as the functional Head of Government as the “right hand of the King”; he or she serves as the presiding officer over meetings of the Conshilía Purpháidhe, has direct oversight of all its ministers and ministries. The Procurator determines the government's official program of policies that it will implement, although members of the Purpháidhe are under no obligation to follow the policies. The Procurator also serves as First Lord of the Treasury, giving them the authority to create and issue Royal Budgets for the Kingdom in the name of the King that must be approved by the Conshilía Daoni. The Procurator has no formal ministry under them but is responsible for the nomination of the Lord Marshal, who serves as both the military and civilian head of the Ministry for the Armed Services. The Procurator also serves as the Lord Regent of the Apostolic Kingdom in the event of the absence or minority of a King. Since the time of the Great Interregnum, the Procurator has also served as the Magister Militum of the Armed Forces of the Apostolic Kingdom of Urcea, giving him or her effective supreme command and control over the military. Elections for the Procurator are held every five years on the first Tuesday in November, and Procurators take office on the first of January following the date of the election. There are no term limits on the office of Procurator. The Procurator may veto legislation passed by the Conshilía Daoni, though he does not sign legislation into law. The Procurator is also responsible for appointment of Rectors of overseas territories through the person of the King, though unlike other appointments on constitutional advice the King has greater influence in the appointment of Rectors.

The Royal Treasury is chartered by the King and functionally serves as the central organ within the national bureaucracy, coordinating with the various Ministries and other Royal organizations to implement programs and policies via budget lines and supplemental appropriations. The Royal Treasury is funded through various mechanisms which the Kingdom uses to tax. As noted above, the Procurator is First Lord of the Treasury and controls broad policy directives for the Treasury, but the day to day operations of the Treasury are under the purview of the Chancellor of the Treasury, although nothing precludes the Procurator and Chancellor from being the same individual.

The Conshilía Purpháidhe, known as the "Purpháidhe", serves as a practical executive branch and Cabinet, though its original function was that of privy council. The members of the Purpháidhe are members of the Conshilía Daoni (known as the “Common Council”) nominated by the Chancellor and Temporary President through his or position as head of the Conshilía Daoni with the exception of the Ministry for the Armed Services and Ministry for the Church in Urcea, who have special appointment rules. The various Ministers of the Concilium serve as the head of various Ministries that are akin to executive agencies, and the national bureaucracy is organized through them. Much of the nation's national policymaking comes through the regulatory rule-making power statutorily authorized to the various Ministries of the Purpháidhe; these regulations, rules, and pseudo-laws do not require Royal or Daoni assent if they have statutory basis but rather require the imprimatur of the Procurator. If a member does not follow official directives of the Procurator, called "Treasury Orders", the Procurator may issue a formal request to the King for an order of compliance. Members of the Purpháidhe can also ask the King for arbitration in the event that the Procurator refuses to issue an imprimatur for their proposed course of action. The King may take three options: he can issue a "Writ of Compliance", ordering the Purpháidhe member to follow the Procurator's direction; he can issue a "Writ of Correction", in which the Procurator must withdraw his Treasury Order, allowing the Purpháidhe member to proceed on their own proposed course of action submitted to the King; or, the King can issue a "Writ of Dismissal", in which neither the Purpháidhe member's proposal nor the policy designed by the Procurator may be followed and that an entirely new policy must be devised. Constitutionally speaking, the King may issue a narrowly tailored suggestion following a Writ of Dismissal, but neither the Purpháidhe member nor the Procurator are under any legal obligation to follow or implement the King's suggestion, though the King's word is normally considered to be very influential and, politically speaking, the King's suggestions are rarely refused in these circumstances. Due to the sensitive nature of foreign policy, the Procurator retains a small corps of ambassadors known as the Treasury Ambassador Service which can conduct foreign policy on the Procurator's behalf in the event of an impasse between the Ministry of State and Procurator.

Sitting on the Purpháidhe are the two Censors, who are responsible for maintaining the census and supervising public morality. Besides the administrative necessities of the decennial census, the Censors issue regulations for content censorship in the media, and additionally must issue a report on impacts on morality and public virtue of a proposed piece of legislation before the Conshilía Daoni. The Censors do not have full veto power, but rather lodge formal "Objections", which by themselves are influential enough to halt a bill or bring about an amendment. Both Censors, in concurrence, can issue a suspensive veto for a bill, forbidding the legislation from being voted on for the remainder of the year unless more than eighty percent of the members of the Daoni vote to override. When both Censors issue an objection, the Apostolic King of Urcea can also legally veto a bill, though in those circumstances the Procurator typically vetoes the legislation rather than the King in order to preserve perceived democratic legitimacy. The Apostolic King of Urcea selects a list of potential candidates from among a list of self-declared candidates for the office, and from this list the Urcean Conference of Catholic Bishops selects four candidates who are elected by the nation as a whole. Censors can run for reelection provided the Conference of Catholic Bishops include the incumbent on their list of candidates, and it is highly unusual for the Bishops to refuse ballot access to an incumbent.

Legislative Branch

Urcea's legislative branch consists of two chambers. The primary body, called the Conshilía Daoni or Common Council, traces its lineage back to the tribal assembly of Great Levantia. The Procurator is the nominal president of the Common Council, but the primary leader of the Council is the Chancellor and Temporary President as detailed below. The Conshilía Daoni is the primary legislative chamber, having authority over nearly all aspects of governance besides that of trade, the guild law, and matters pertaining to the Estates of Urcea; those matters are handled by the Gildertach and King, respectively. The Gildertach is sometimes referred to as Urcea's upper chamber, and it is the representative of Urcea's guild system, with each guild equally represented with voting membership.

Conshilía Daoni

The Common Council (also known as the Conshilía Daoni) is a popularly elected body that serves as the lower chamber and primary house of the national legislature of the Apostolic Kingdom. Originally constituted as a meeting of the commons to approve or disapprove tax levies by the King, the Daoni has taken on broad legal powers in all policy areas. Members of the Daoni are called Delegates, and the members are organized into party conferences, with each party having its own leader. Though the Procurator is the legal and nominal presiding officer of the Council, Constitutional precedent calls for the election of a Temporary President. Since the middle of the 19th century, the Temporary President has served in the role of Chancellor of the Royal Treasury and has had the ability to nominate the members of the Purpháidhe, giving rise to the office of Chancellor and Temporary President, who serves as the head of the legislative branch. The Chancellor and Temporary President also usually serves as leader of their party, and as a consequence, typically holds the title of Majority Leader of the Conshilía Daoni. The leader of the largest minority party serves as Leader of His Most Christian Majesty's Loyal Opposition.

Like the Procurator, elections for Delegate are held every five years on the first Tuesday in November, and new sessions of the Conshilía Daoni begin on the first of January following the date of the election and last for five years. Election districts, called Delegations, are single-member and first-past-the-post, and boundaries of each Delegation are determined decenially following each decade's census. The number of Delegations has been set at 500 since the Second Great War.

The Conshilía Daoni is organized into committees corresponding to the different Conshilía Purpháidhe ministries, with each minister also serving as Chair of the respective committee they are Minister of. Each committee also has a ranking minority member from the largest minority party, and the role of ranking member doubles as shadow minister. Given the workload of serving as head of a Ministry, Ministers very rarely get involved on a more than superficial level in the affairs of their respective committees, with staff or other Delegates doing much of the work.

Besides considering and passing legislation, the Conshilía Daoni has several important functions. Filling the role of Chancellor and Temporary President is necessary for the functioning of government given the role the Chancellor plays in filling the Conshilía Purpháidhe, so the election of a Chancellor and Temporary President is often the first item of business considered by a session of the Conshilía Daoni. The Conshilía Daoni is responsible for approving any international treaties to which Urcea is a signatory. In addition, the Conshilía Daoni is responsible for passage of a Royal Budget every fiscal year, which begins on April 1st. The Procurator must propose a budget to the Daoni by January 15th each year, and negotiations proceed from there. Constitutionally, the Daoni may not add language to the budget, but may change funding lines or remove language. If negotiations between the Chancellor and Temporary President and Procurator break down, the King has the authority to extend the previous year's budget, as noted above. If an agreement is reached, the Conshilía Daoni considers and votes on the budget bills as modified by any negotiations or agreements since the Procurator first proposed them.

Though defunct, the Imperial Diet, the legislative body of the Holy Levantine Empire which created trade conditions and regulations throughout the Empire, served as a critically important legislative institution in the Urcean government. The King, as both King and as Elector, functionally had the right to nullify proposed laws, and beginning with the ostracization of Urcea following the Second Caroline War, most of the dictates of the Diet were nullified in Urcea, giving rise to the need for a stronger Conshilía Daoni to take its place.

Gildertach

The Gildertach is a body sometimes referred to as the upper chamber of the legislature, and is made up of five elected representatives from each guild in Urcea. The Gildertach's membership is non-partisan, and its meetings are presided over by the Apostolic King of Urcea, or, more regularly, a designee of the King. Its primary responsibility is twofold; it considers proposals from the Conshilía Daoni and Ministry of Commerce with regards to trade deals, and it is responsible for amending the guild law which governs its members and the way that guilds function. Much of the business of the Gildertach primarily consists of deliberations on establishing new guilds or splitting existing ones based on technological advancement or economic diversification. With such a limited mandate, the Gildertach does not meet regularly, and it is possible (though rare) that the Gildertach will not meet at all during a five-year electoral cycle. Consequently, it's heavily debated among political scientists whether or not the Gildertach truly qualifies as a legislative chamber or not, and in common parlance it is often claimed and believed that the Conshilía Daoni is the only part of the national legislature.

Judicial branch

The Urcean judicial system is comprised of a three-tiered court system, and each tier of court is divided into appeals, civil, and criminal divisions which share the same physical infrastructure as well as some personnel and judges. In this system, appeals work in a hierarchical manner, with each higher tier up being the appellate division for the lower courts. The lowest tier are the Diocesan Courts, which serve the civil dioceses that divide the country. These courts are the most common and typically are responsible for overseeing civil disputes between individuals or firms. Diocesan courts also oversee prosecution of petty and local crimes. The next highest tier is the thirty four subdivision-wide courts, whose name varies based on the type of subdivision, but the most common title is "Provincial Court" or "Supreme Court". The provincial court tries grave crimes and civil cases where the parties are from different lower jurisdictions. The third tier of courts are called the "conrudimental courts", with conrudiments being comprised of two to three provinces. The conrudimental courts are responsible for trying violations of national crimes as well as civil cases with parties originating from different provinces; if a civil case involves parties from different conrudiments, the Ministry of Justice is responsible for choosing which conrudimental court will try the case. Within The two autonomous states have conrudimental courts entirely coterminous with the respective states. The Archducal Court of the Archduchy of Urceopolis serves as the nation's highest appeals court as a prime court and does not exist within any of the conrudiments.

National Politics

Typically, the political leadership of the Urcean Government can take four distinct forms. In the first, following an election, the Procurator and the Chancellor are the same individual or from the same party; same party candidacies are uncommon but not unheard of if a party's Conshilía Daoni leader does not have widespread popular appeal and electability. In this scenario, this party are in total control of the government and the Chancellor-Procurator controls the appointment of the members of the Conshilía Purpháidhe and the policies that the Purpháidhe follows, leading to the party's policy program and budget being implemented. The second scenario involves a Procurator and Chancellor of different parties who form what's called a "Purpháidhe Coalition", whereby a minority of members of the Purpháidhe are appointees of the Procurator's party in exchange for a mutually agreed upon policy program being established by the Procurator; in this scenario, the Chancellor is usually the more powerful of the coalition partners. The third scenario requires a hung Daoni, whereby the Procurator guides his party to form a coalition with another party to elect a Chancellor of the other party. This scenario is called a "Daoni Coalition", and the appointed membership of the Purpháidhe is typically an even split. In this scenario, the Procurator is typically the more powerful of the coalition partners. The final scenario involves a Chancellor and Procurator of different parties who cannot come to an agreement. In this scenario, the Procurator's program is often in conflict with members of the Purpháidhe, requiring constant intervention of the King over Treasury Orders, and many times in this scenario King's Budgets are implemented. This final scenario is often called "Royal Rule", because the King, in his role as arbitrator, is most accurately said to be the one governing the Kingdom.

During the 20th century, political power switched between the two largest parties - the National Pact, the dominant party of the 19th century, and the Commonwealth Union, formed in the midst of the Red Interregnum. This bi-partisan divide continued until the 2015 Urcean political realignment. Despite the predominance of the two major parties, other smaller parties such as the Julian Party and the Democratic Labor Party did hold office throughout the country in the era. In the 21st Century, the Commonwealth Union held a majority in the Daoni every session except for 2006-11, when the National Pact under the leadership of Michael Redder took a slim majority in the legislature. By contrast, the National Pact has held the Procuratorship for the whole of the 21st Century except from 2016-2025. After the dissolution of the Commonwealth Union in 2015, the Democratic Labor Party became the second largest party in the Conshilía Daoni with the National Pact surging to a majority in the 2015 Urcean elections. The Democratic Labor Party later reorganized the left into the united Social Labor Party in the wake of the 2015 Urcean political realignment and the Casanam Conference. Soon after, the Union for National Solidarity reformed out of the Wittonian-Reedian faction of the old Commonwealth Union. In 2025, the Union for National Solidarity and Julian Party merged to form the Solidarity Party, which became the largest party in Urcea upon its formation.

Subdivisions

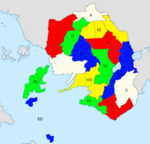

The federal subdivisions of Urcea take three distinct forms as defined by the Administrative Reorganization Act of 1892, a major reform implemented during the regency of Gréagóir FitzRex. Most of the country is organized into provinces, which are a basic federal unit considered constituent parts of the Kingdom. Besides the provinces, there are crownlands - lands held directly by the Apostolic King of Urcea by merit of his other titles - of which two are considered the only integral parts of the Kingdom, the Archduchy of Urceopolis and Grand Duchy of Harren as defined by the Golden Bull of 1098. The remaining crownland, the Electorate of Canaery, is not integral to Urcea but enjoys pride of place as the sole remaining electorate of the mostly defunct Holy Levantine Empire. The final form of government are states, which were created for two of the most prominent minority groups in Urcea - the Gassavelian people and the Ænglish people. Each of the three forms of government have different representative and administrative structures. Prior to the Royal and Provincial Tax Act of 2020, each of the three types of subdivisions paid a separate kind of tax to the central government, but all of these systems were replaced with a national income tax.

Crownland

Crownlands, sometimes also called "Royal Holds", are lands directly held by the Apostolic King of Urcea through some other title other than King. Two of these crownlands, the Archduchy of Urceopolis and There are three such crownlands, though several more - such as the Kingdom of Crotona - existed prior to the 1890s. Each crownland has a unicameral elected Royal Parliament. The Parliament functions as a de facto legislature for the crownland, though all proposals and laws are nominally issued in the name of the King. Each crownland has a Governor-General of the Realm, which are appointed by the King on the advice of the Purpháidhe, who serves as de facto executive officer within the crownland. Appointments are generally made factoring the individual needs of each crownland; each has its own tradition and precedent regarding the appointment of Governor-General, ranging from Urceopolis's non-partisan appointment to Canaery's parliamentary nomination model.

Province

Provinces are the most numerous of the three types of sub-national governance; there are twenty-nine provinces. These are considered to be general federal entities that are not directly held by the King as a separate title, but rather are tied to the Kingdom itself as a legal entity. The legal precedent has been established through successive rules and statutes that constitute a General Code for the Provinces, which creates for the provinces a representative form of government which is uniform throughout all of Urcea's provinces. Each province has an elected bicameral legislature (with the two houses generally called the Senate and Assembly) comprised of electoral districts determined decennially based on the decennial census, an elected Governor who serves as the province's chief executive, and a provincial Supreme Court under the purview of the Ministry of Justice, with some members appointed by the King as a "Royal Judge" and approved by the provincial legislature and with some members being appointed by the Governor. Each province exercises a degree of home rule and has somewhat wide latitude in implementing local legislation.

State

The third form of governance is the semi-autonomous state, the least numerous of the three types; there are two such states. Unlike the provinces and crownlands, states are generally free of the royal bureaucracy and are free to construct the confines of their state as applicable, and are also free to determine their own form of governance with consent from the King in the form of an issued charter. Despite their autonomy from many of Urcea's governmental functions, they are represented within the Conshilía Daoni. In practice, all of the states emulate the form of government as the provinces, though the Chief Executive is called Secretary-General rather than "Governor". The state is generally reserved for cultural enclaves within the Apostolic Kingdom; Ænglasmarch for the Ænglish people and Gassavelia for the Gassavelian people.

Local Government

Every province, crownland, and state is divided into dioceses which are coterminous with the episcopal diocese of the Catholic Church, though the so-called "civil diocese" have very little administrative or political function and have two main responsibilities. Primarily, diocesan division is a method by which judicial districts are determined; judicial responsibilities are not held at the municipal level and there are almost no municipal courts save for in Urceopolis. The second responsibility handled at the diocesan level is that of national elections, with Diocesan Boards of Election being responsible for the planning and execution of elections for Procurator, Censor, and members of the Conshilía Daoni; if municipalities use the "executive" model described below, the Diocesan Board of Election also oversees elections for those local offices. Below the diocesan level exists the three basic types of local government; the civil commune, the guild commune, and the executive polis. In each of these three systems, the school district is entirely coterminous with the municipality, though each of the three systems have a different method by which the local school district is administered. The entirety of the Apostolic Kingdom is thus divided into municipal boundaries with no unincorporated areas. This system was brought about largely during the regency of Gréagóir FitzRex, as dioceses replaced counties in the mid 1890s; under the previous system, most counties had no sitting count with authority devolving back to the Crown, though some counties had counts who retained hereditary political power. FitzRex also introduced the executive polis system and planned for it to be used for every locality in the country by 1905, but the Red Interregnum canceled implementation of that reform.

Civil commune

The most common type of local governance in Urcea is that of the civil commune, the oldest form of local government currently in place originating in the practices of cities in the Medieval period. The commune functions through town meeting, a form of direct democracy whereby the members of the locality vote on legislation and issues of local importance in addition to having authority to set budgets and adopt zoning plans. The commune's assembly also exercises total control over the local school district. In the civil commune, any citizen owning property or having a substantial financial stake, such as a job, within the commune ages 21 or older can vote at the town meeting. A moderator is typically elected at the first meeting of a calendar year and serves for the remainder of the year, and the moderator has no delineated powers other than maintaining the rules of order. Within the assembly, there are committees formed typically either by volunteers or by drawing names from a hat or bin, and members of committees serve for a calendar year Communes maintain small governments apart from the assembly, appointing permanent paid individuals to oversee areas such as highway and sewer maintenance. These hired individuals are usually subject to the authority of a committee within the commune's assembly relating to that area of governance, with the exception of police chiefs, who are subject to oversight only by the assembly as a whole. Civil communes are usually employed for rural municipalities, but are also the most common type of government employed in suburban areas of the country as well. By national law, communes can not be used for large municipalities and cities of over 220,000 people.

Executive polis

The second most common type of local government is that of the executive polis, which entails the fairly typical system used abroad employing a mayor and city council. This system was introduced with the Administrative Reorganization Act of 1892 by Gréagóir FitzRex, and previously had only been reserved for Urceopolis, which uses a similar system except the executive is entitled "Lord Prefect". These are now used only for the largest cities throughout the nation, including the cathedral city of each of Urcea's holds, provinces, and states. The executive mayor is responsible for the administration of the city and works with a municipal legislative branch, the city council, to handle the affairs of the city. The city council is elected by the all citizens of the city of voting age, and each city using this system is separated into election districts called wards. Under this system, separate zoning boards and boards of education are also elected to handle those respective areas. Elected officials under the executive polis serve five year terms that are coterminous with members of the Conshilía Daoni, and consequently these localities follow the electoral calendar of national elections. These cities have relatively large executive branches, with department heads nominated by the mayor and confirmed by the city council.

Guild commune

The third and most rare common type of local government is the guild commune. This system, like the civil commune, finds its origins in the medieval period, though they were very rare compared to civil communes and were more widely implemented during the industrial revolution by King Aedanicus VIII in the face of the inability of both communal and prefecture governments to properly govern growing cities. This system is very similar to the civil commune except it has a more restrictive, hierarchical approach to membership in the assembly. It employs an assembly of Guild members serving in a similar governing capacity as the civil commune, with every vested member of a guild entitled to a vote before the assembly in the commune. This system is considered to be pseudo-democratic and representative, as non-vested members of the guilds - the vast majority of individuals typically living in a guild commune city - have a responsibility to select who is vested within their respective guild. Like the civil commune, the guild assembly has the ability to hire permanent employees of the commune to oversee municipal affairs. Unlike the civil commune, the hired apparatus in a guild commune is often much larger than that in a civil commune, given the large size and scope of administering a city. Consequently, the guild commune is often viewed as something of a compromise between the executive polis, with a representation structure overseeing a large municipal bureaucracy, and the civil commune, with an assembly-oriented methodology of governance rather than a strictly composed legislature. Guild communes are typically concentrated in historic industrial centers where the influence of the guilds were in higher demand, and most guild communes were established during the industrial revolution. Many transitioned to the executive polis model during the mid-20th century.

Prefectures

Prior to the reform of 1892, there was another kind of local government in place, prefectures. Prefectures were extremely common and were employed for cities and areas that did not traditionally enjoy communal rights and privileges. Under these prefectures, the highest local hereditary authority would directly appoint a prefect to govern a region and create an administration under them. Prefects would serve as long as they had the confidence of whoever appointed them. Prior to the Great Confessional War, the local nobility typically appointed the prefects, but following the conflict the Apostolic King of Urcea assumed direct control over vast swaths of the country. Appointment of prefects became a time consuming affair for the Crown and the inability to oversee so many local prefects was the source of corruption and poor governance in many parts of the country. Many major industrial cities were transitioned from prefectures to guild communes during the 18th and 19th centuries. King Aedanicus VIII swept away most of the prefectures during his reign, granting communal rights to most areas and elevating some guild communes elsewhere, but a handful remained in place until the entire country was reorganized in by Gréagóir FitzRex in 1892. Prefectures were not always permanent institutions; oftentimes they would be used to organize new Ómestaderoi regions or reclaimed land until such time that a civil commune could be established. Prefectures in this manner were also used under the Rectory system for newly acquired territories in Levantia, most especially in the Kingdom of Crotona as pre-existing feudal units did not exist in the primarily city-state dotted islands.

Overseas Possessions

Overseas possessions of Urcea are organized under the supervision of a Rector and are consequently called "rectories", divided into "civil rectories" and "military rectories". Rectors were originally established as temporary governors of newly conquered territories, representing the Apostolic King of Urcea in a viceregal capacity until proper government could be established locally. This system was adapted for Urcea's overseas acquisitions on a permanent basis, and it remains the system presently in use. Rectors are appointed by the Apostolic King of Urcea in consultation with the Procurator, and the King exercises a fairly large degree of discretion on appointments of Rectors unlike some other positions in the government where he appoints using the constitutional advice of the Procurator or Chancellor and Temporary President. The precedent established in the Constitution of Urcea by various appointments beginning with Aedanicus VIII holds to the principle that Rectors govern overseas possessions in the King's name, so the King should retain input on who is governing in his name. This precedent survived through the years of the Red Interregnum and was firmly established by Patrick III, even as other government offices were becoming increasingly subject to the oversight of the Conshilía Daoni and Procurator.

Civil rectories, such as Medimeria, are civilian governments overseeing smaller territorial possessions such as overseas islands. Though the Rector is appointed by the Apostolic King of Urcea, the territory is organized into local governments like in the Urcean metropole. Typically, the rectory is small enough that there is no need for the creation of provinces or other districts between the rectory government and the local governments, so the former directly oversees the latter. In civil rectories, Rectors are given wide ranging authority to organize their own territorial government, though formal precedent has led to the "inheritance" of an established bureaucratic and governmental apparatus from one Rector to another. Civil rectories all have informal "island assemblies" made up of representatives from the various elected local governments within the rectory, and these island assemblies have wide-reaching if non-binding authority in the form of consultation with the Rector, whom typically defers to the cultural experience and knowledge of the local leaders. Outgoing Rectors often bring their prospective successors to these assemblies for their non-binding "ratification" and report the results back to Urceopolis; local opposition is often justification for pulling an appointment for Rector.

Military rectories, such as Cetsencalia during The Deluge, are military governments overseeing territories in transient political states or territories near combat or war or are the subject of a war. These territories are typically directly overseen by theater commanders of the Armed Forces of the Apostolic Kingdom of Urcea, though they typically delegate political authority to subordinate committees. Like civil rectories, local governments are either maintained or organized like those in Urcea, but the military oversees the affairs of local governments in a manner similar to marital law. Military rectories do not convene territorial assembles like the civil rectories do. Unlike any other organ of Urcean governance, military rectories are divided into districts overseen by a local commander. Unlike civil rectories, military rectories are always a temporary expedient that lasts the duration of a military or diplomatic crisis, such as occupied territories during the Second Great War, and are usually dissolved into civil rectories or regain sovereignty following the cessation of hostilities. Military rectors are usually the rank of Prafáti Princeps and are almost always members of the Royal and Imperial Army. Prior to 2027, Military Rectories were usually held by the theater commander. However, the significant amount of territories that fell under Urcean occupation during the Final War of the Deluge concentrated multiple territories under the command of Martin St. Clair, creating administrative issues. The Foreign Occupation Act of 2027 decoupled theater command from territorial governorships in certain cases and allowed the Procurator to directly appoint a military governor on the advice of military leaders.