Pursat: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

mNo edit summary Tag: 2017 source edit |

||

| Line 317: | Line 317: | ||

==Government and politics== | ==Government and politics== | ||

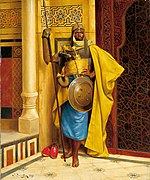

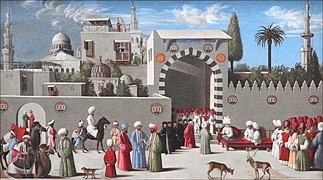

[[File:Bukhara by Pouria Afkhami aka pixoos 05.jpg| | [[File:Bukhara by Pouria Afkhami aka pixoos 05.jpg|thumb|left|The Great Fort, the capital complex of Pursat]] | ||

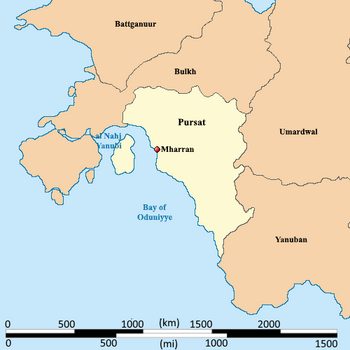

[[File:PursatPoliticalMap.png|thumb|right|Political map of Pursat.]] | |||

The central government of Pursat is in its capital city Mharran, home to around 4.2 million people. The government's complex known as "The Great Fort" is the ancient citadel of the city and currently hosts both branches of the government. | The central government of Pursat is in its capital city Mharran, home to around 4.2 million people. The government's complex known as "The Great Fort" is the ancient citadel of the city and currently hosts both branches of the government. | ||

===Executive and judicial branch=== | ===Executive and judicial branch=== | ||

Revision as of 09:24, 24 July 2024

Muwahhidnn State of Pursat Pursat | |

|---|---|

|

Flag | |

Motto: I enjoin you to safeguard your fellow men. In safeguarding them your faith reaches perfection. Passage from the Epistles of Wisdom | |

Map of Pursat | |

| Capital and | Mharran |

| Official languages | Pursi |

| Recognised national languages | Arabic, Burgoignesc |

| Ethnic groups | Pursi, Kemeti, and Ebidi |

| Demonym(s) | Pursatnieen |

| Government | Theocracy |

• Supreme Professor | Amin al-Atrash |

| Establishment | |

• Independence from the BRTC | 1795 |

| Area | |

• | 610,667.397 km2 (235,780.000 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• Estimate | 161,058,500 |

• Density | 263.741/km2 (683.1/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal) | estimate |

• Total | $2,029,498,158,500 |

• Per capita | $12,601 |

| Currency | Pursatni Taler (PT) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+0 |

| Date format | dd-mm-yy |

| Driving side | right side |

| ISO 3166 code' | P₮ |

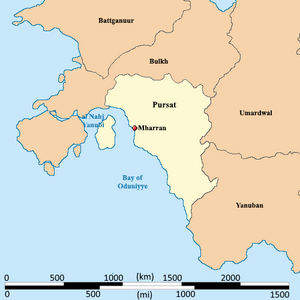

The Muwahhidnn State of Pursat, often just called Pursat, is a rapidly modernizing nation in southwestern Daria region of Audonia bordered by the Bay of Oduniyye in the west, Bulkh in the north, Umardwal and Yanuban in the east and south. It was massively urbanized in the 1980s and 90s and has a very high population for its landmass. Its executive is a president for life, but it does hold democratic elections for its legislative branch and local offices.

Pursat is a member of many international organizations like the League of Nations, the ISO, Red Crescent International, etc. and many other regulatory and economic bodies.

It is a market economy focused on exports, under the watchful eye of Burgundie, whose companies have a massive stake in the country's economic activity. It specializes in the assembly of microprocessors and cellphones, as well as the cultivation of tropical hard woods, fishing, and rubber, which also constitutes its major exports.

The people of Pursat are predominantly culturally Pursi, Kemeti, and Ebidi, the official language is Pursi, with Arabic and Burgoignesc being secondary languages, and most practice Druzism.

Etymology

Pursat is a transliteration of the Aramaic word pirsa meaning lust with the tay merbutah the final "t" sound meaning the place lusted after. It was referred to as such because of its beautiful landscape and rich resources. Some scholars have postulated that it could have been the location of the real life inspiration for the Biblical Garden of Eden.

Geography

Pursat is bordered by Bulkh to the northwest, Umardwal to the east, Yanuban to the southeast and Umardwal and the Great Kavir desert to the north. Pursat's borders are marked by several significant rivers. The Iteru and Lilu Rivers form the country's northwestern border with Bulkh, while the al-Firat River delineates its eastern border with Umardwal. Off the northwestern coast of Pursat, in the Bay of Oduniyye, lies the low-laying island province of Fapimunein, which is semi-arid. The most prominent geographical feature of mainland Pursat is its expansive coastal plain, stretching along the country's northwestern to southeastern coastline. This plain is characterized by a gradual slope, rising from the sea level towards the interior. The plain is predominantly semi-arid, with limited rainfall supporting scrub vegetation and scattered oases. Two mountain ranges, the Zagrin Mountains in the northwest and the Baqunah Mountains in the southeast, define the boundaries of the coastal plain. These ranges create a natural barrier, influencing the climate and providing a source of water for the surrounding regions. The Zagrin Mountains, particularly, offer a more temperate climate, contrasting with the aridity of the coastal plain. To the north of the coastal plain lies the Great Kavir desert, a vast expanse of arid land characterized by sand dunes, salt flats, and extreme temperatures that spans Battganuur, Bulkh, Pursat, and Umardwal. The desert, through desertification, has continued to push southward, reducing the semi-arid coastal plain by 35% in the last 300 years, but 14 percent of the total was in just the last 75 years.

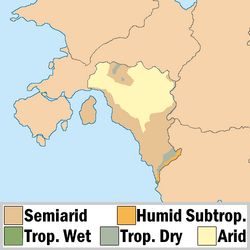

Climate

Pursat's climate has a semi-arid climate in the coastal plain, with hot summers and mild winters. The Great Kavir desert to the north amplifies the aridity, with extreme temperatures and minimal rainfall. The Zagrin and Baqunah Mountains, the countries northwestern and southeastern regions respectively, provide a more temperate environment, with cooler temperatures and higher precipitation compared to the surrounding areas.

Annual precipitation varies from 500 to 900 mm (19.7 to 35.4 in) depending on the region with an average of 590 mm (23.2 in). Cyclones are also common during the wet season. Average temperature ranges in Mharran are from 13 to 24 °C (55.4 to 75.2 °F) in July to 22 to 31 °C (71.6 to 87.8 °F) in February.

| Climate data for Mharran | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 29.9 (85.8) |

29.6 (85.3) |

29.3 (84.7) |

27.8 (82.0) |

26.4 (79.5) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.4 (75.9) |

25.3 (77.5) |

26.1 (79.0) |

26.5 (79.7) |

27.4 (81.3) |

29.1 (84.4) |

27.2 (81.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.3 (79.3) |

26.2 (79.2) |

25.6 (78.1) |

23.5 (74.3) |

21.4 (70.5) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.8 (65.8) |

20.0 (68.0) |

21.5 (70.7) |

22.4 (72.3) |

23.8 (74.8) |

25.5 (77.9) |

22.8 (73.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 22.3 (72.1) |

22.3 (72.1) |

21.5 (70.7) |

19.4 (66.9) |

16.9 (62.4) |

14.4 (57.9) |

14.2 (57.6) |

15.4 (59.7) |

17.2 (63.0) |

18.3 (64.9) |

19.7 (67.5) |

21.4 (70.5) |

18.6 (65.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 171.1 (6.74) |

130.5 (5.14) |

105.6 (4.16) |

56.5 (2.22) |

31.9 (1.26) |

17.6 (0.69) |

19.6 (0.77) |

15.0 (0.59) |

44.4 (1.75) |

54.7 (2.15) |

81.7 (3.22) |

85.0 (3.35) |

813.6 (32.04) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 8.1 | 7.6 | 7.0 | 4.4 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 3.2 | 5.5 | 7.9 | 7.5 | 60.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76 | 76 | 77 | 76 | 74 | 73 | 72 | 71 | 73 | 75 | 75 | 74 | 74 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 223 | 210 | 225 | 229 | 253 | 246 | 256 | 252 | 228 | 210 | 198 | 220 | 2,750 |

| Source: ur mom | |||||||||||||

History

Prehistory

The earliest human settlements in modern-day Pursat trace back to the Paleolithic era, evidenced by rudimentary stone tools found near the fertile banks of the local rivers. As agriculture emerged during the Neolithic period, the inhabitants established small villages and began cultivating grains (wheat and pulse is attested in the archeological record) and domesticating animals, namely dogs and several types of water fowl. By the early Bronze Age, a distinct culture began to take shape, characterized by its unique pottery and jewelry. Throughout this epoch, the people in Pursat experienced gradual cultural and technological advancements, laying the foundation for the emergence of a future complex civilization.

Classical Antiquity

-

The Great Stones

-

Remnants of the Great Library of Kussaipis

-

Ruins of the power naval city Aknosheh

-

Kemeti ropework

In the 9th century BCE, the Kemeti people rose to prominence as a regional power, establishing trade networks with neighboring civilizations and developing a sophisticated system of writing based on hieroglyphs. The Kemeti pantheon, featuring gods like Re, the sun god, and Isus, the goddess of fertility, became central to Kemeti religious life. During this era, monumental structures like the Great Stones and the Temple of Amin were constructed, showcasing the Kemeti's architectural prowess. They were great slavers and traders of fine goods all along the Bay of Oduniyyad and they were also connected into the Sea of Istroya trade network. As desertification of the Great Kavir pushed some closer to the coast, the Kemeti became war-like and centralized capturing most of modern Bulkh, Pursat, Yanuban, parts of southern Umardwal, and Syliria. The Kemeti dominated the local Arabs and Pursi people.

In 42 AD, the Coptic Christian faith was founded in Pursat and local Arabs and Pursi adopted it very quickly despite violent pushback from the Kemetis.

By the 7th century AD, the once-mighty Kemeti civilization had endured millennia of prosperity and dominance. However, internal strife, political instability, and the pressure of neighboring empires had gradually weakened the Pharaonic state. The final dynasty, the Pe-ankh-em-tanenids, weakened by corruption and economic decline, struggled to maintain control over its vast territory. In 739, the armies of the Oduniyyad Caliphate, set their sights on the Kemetis. Led by the brilliant general 'Amr ibn al-'As, the Arab Muslim forces swiftly crossed the frontier and engaged the Kemeti army at the Battle of Fapohdet. Despite their valiant efforts, the Kemeti forces were no match for the disciplined and highly motivated Arab Muslim army. The defeat at Fapohdet marked the beginning of the end for the Kemeti civilization.The Oduniyyad Caliphate forces continued their advance, capturing major cities and fortresses across the . In 842 AD, the cultural and intellectual heart of the Kemeti civilization, Medvasut, fell to the invaders. The Great Library of Kussaipis was burned down by the rampaging Caliphal forces marking the end of the Kemeti civilization, at least as a centralized state. Remnants of the Pharaonic retinue and army fight for three more years but they were never victorious and the Pharaoh Atemu III died, alone in the streets, in 843, his family and heirs all killed by the Oduniyyad Caliphate.

Medieval period

-

Mamluking good

-

Kemeti papermaking

The medieval period in Pursat was marked by the wars with and eventual occupation by the Oduniyyad Caliphate. During this time, Pursat became a crossroads of cultures and religions, while Islam was the state religion, the Beys of Pursat, as the Caliphal province was called, allowed some dhimmi, with Coptic Christianity and traditional Kemeti beliefs allowed in the province, but active conversion efforts throughout the tenure of the Caliphate meaning that over 80% of the province were reported as Sunni Muslims by 1150. Intellectual pursuits flourished under Arab rule, with Pursat's scholars making significant contributions to fields like mathematics, astronomy, and medicine. Pursati architecture also underwent a transformation, incorporating Islamic influences into its designs. The Beys of Pursat were very wealthy and respected among the Caliphal court.

It was during this time that the Druze faith was founded in Pursat and many of the Coptic Christians converted as it was most aligned with Islam and therefore more tolerated by the Arab Beys.

Early modern history

Eloillette colony was a colonial holding administered by the Bourgondii Royal Trading Company from 1526 until 1795.

The first Burgoignesc permanent settlement in the area of Eloillette was a factory in modern-day city of Cusmarna, called Port d'Ostroise, in the Burgoignesc language, in 1526. Port d'Ostroise had become a massive hub for the export of Eloillettien cordage, line, paper, and legumes by the 1600s. The Duchy of Bourgondia and the Principality of Faramount expanded their presence in the area following the conclusion of the Great Confessional War by awarding Patroonships to loyal Catholic vassals. These patroonships in the 1610s constitute the first formal colonization of modern Eloillette by Levantines.

In the 1630s silver was discovered in the east and a rapid expansion took the small, coastal settlements deep into the heartland. The silver mining villages were sprawling, under-policed, and full of people of all ethnicities and origins. It also raised the colony's profile and ultimately led to its demise. Accounting was rudimentary at best, and corruption and theft were commonplace. Based on modern geological estimates, only about 57% of the silver mined in Eloillette made its way to Levantia through official channels. The Duchy of Bourgondi bought out the Principality of Faramount's colonial shares and started a desperate and authoritarian effort to extract all of the silver from Eloillette. This caused massive inflation in the Duchy of Bourgondi as massive amounts of silver poured in in the late 1680s through 1720s. The 40-year period of inflation weakened the Occidental purchasing power of the Duchy of Bourgondi but saw massive investment in its colonial empire as it tried to spread out the silver to reduce inflation. During this time the need for workers in the mines led to a massive slave trade into the colony. 340,000 peopled were transported to or within Eloillette between 1650 and 1795. The endless silver mining meant that, in essence, there was an insatiable feedback loop of silver to buy slaves to mine more silver, to buy more slaves. This demand for slaves went beyond religious or political boundaries and many colonies from other Maritime Dericanian states were happy to sell slaves in exchange for Eloilletten silver.

Eloillette was unique in the Audonian Burgoignesc_colonial_empire in that it was, in so far as the Occidentals present, a majority Catholic colony, instead of majority Protestant. This did lead so some conflicts with the surrounding Istroya Oriental and Kandahari-Pukhtun colonies with sectarian violence breaking out on the borders in 1639, 1654, 1679, and 1748. These clashes were typically localized and only between the Occidental inhabitants of frontier settlements. They were typically after a drought or over the discovery of a gold deposit, which were typically small.

In 1775, there was a slave revolt that killed 5,406 Occidentals, mostly women and children, and was brutally suppressed. 2,400 slaves being reported as killed during the revolt and the retributions thereafter. The event decimated an entire generation of the Occidental-class and in the coming years the lack of a young administrative class was felt and the men, many of whom were becoming more and more despondent, were unable or unwilling to effectively manage the mining operations. Alcoholism and violent became commonplace and in 1778 a second slave revolt occured and entire towns worth of people were killed because the men were too drunk to protect them. As the coastally based administration failed to understand the full scope of the problem, they were slow to react and by the summer of 1779 the slaves had full control of the mines and had fortified a number of mining towns. In a disastrous military campaign, the colonial administrators sent 500 troops to try to regain control of the region but over the next three months the troops were caught in a battle of attrition and the Colonel in charge refused to report the poor showing for fear he would be perceived as ridiculous.

For the next 10 years the slaves and colonial troops fought over the territory of the silver mines with reinforcements being sent from the Duchy of Burgoundi and then from the Kandahari-Pukhtun colony but the slaves worked with local tribes and independentists to bolster their numbers. In 1793, the colonial administration was struck by a typhoid epidemic that crippled the colonial leadership and the Bourgoignesc crown took direct control, establishing a viceroyalty. The colony limped along for 3 more years but, devoid of the cash flow of the silver mines and a growing and violent independence movement, the colonists were repatriated back to the Duchy of Burgoundi at great expense to the Duke. This repatriation would become a sticking point as other slave revolts and crises forced the settler stock to abandon more and more colonies through the early 19th century and their metropoles refused to take them back in.

The newly abandoned lands formed a number of ethnically based tribal factions that were nominally united under the banners of the Emirate of Apfumhat on the north and the Sultanate of Pursat in the north. These states, surrounded by the [Istroya Oriental colony|Istroya Oriental]] and Kandahari-Pukhtun colonies were largely cut off from the world, but they, particularly the Sultanate of Pursat, created a network of spies, agitators, and most importantly communicators that would incite and coordinate anti-colonial movements throughout that period. Pursat became a haven for runaway slaves from the Kandahari-Pukhtun colony and formed an army of these runaways to invade the colony in 1803 which exacerbated the existing issues of the colony.

After the collapse of the Burgoignesc colonial empire in southern Daria, Pursat and Apfumhat exercised broad control of the maritime trade routes and pushed their interests across the region for the remainder of the century. The Sultanate of Pursat controlled the silver mines and continued to deal in that trade.

Emirati War

In 1868, a series of passing Burgoignesc clippers were attacked by pirates on the Bay of Oduniyye and blamed the Emirate of Apfumhat. The Navy of Burgundie's Far East Squadron was dispatched to extract reparations but they were refused by the Emir Jafari Al Nasr. The squadron bombarded three port cities and departed. In January 1871, three more clippers were attacked by ships carrying the banner of Apfumhat and the Far East Squadron was once again dispatched. This time they destroyed all of the port infrastructure of the ancient Aknosheh naval station. And landed a company of marines to fill in the harbor. Al Nasr sent a war band to attack the marines and after three nights of fighting, the marines departed to the ships who bombarded the port once more. The Emir's troops suffered heavy losses, but they did not have any artillery support and retired. The Squadron disembarked an entire battalion of marines and occupied the port. In March the Army of Burgundie arrived to conduct a punitive expedition. The ensuing war from March 18th 1871, through May 19th, 1887 was called the Emirati War and featured a series of punitive expedition first in the Emirate of Apfumhat, but by 1879 expanded to include the Sultanate of Pursat. In the 1880s the Army of Burgundie began using its newly established Observation Balloon Corps. It was during this war that the first recorded use of a lighter than air vehicle to drop a weapon occured when a signals color sergeant dropped a fused grenade on a group of Apfumhati warriors as his ballon lost altitude over their position.

The war concluded with the decimation of the Emirate of Apfumhat, Burgundie recognizing and enforcing Pursatni dominance over the lands of Apfumhati, Pursat having to pay T80 million to Burgundie in silver over 30 years, and a permanent naval station and concession port for Burgundie in the city of Konyet. These conditions were initially accepted, but would lead to confrontation between the two countries during the Frist Great War when Pursat cancelled the dept and tried to evict the Burgoigniacs from Konyet.

Late modern period

-

Burgoingesc gunboat in the Bay of Oduniyye during the First Great War

-

Burgoignesc troops entering Mharran during the First Great War

-

Pukhgoignesc Gorkhas of the Burgoignesc Foreign Legion manning artillery in the Great Kavir

-

Pursatni troops in an anti-tank gun hunting for Umardi tanks in the Second Great War

During the First Great War, in 1899, Pursat cancelled the reparations debt it owed to Burgundie in the treaty resolving the Emirati War. Burgundie sent a navy flotilla to urge the Pursatni's to reconsider, but they refused to meet with the emissary. The Army of Burgundie formed a punitive expedition, mostly consisting of Pukhgoignesc Gorkhas of the Burgoignesc Foreign Legion. They Ghorkas were vicious, and the campaign was swift. 6,490 Pursatnieen were killed, three major settlements were taken or destroyed and the government of Pursat was humiliated. They tried to evict the Burgoigniacs from their concession part and naval station in Konyet in 1901, but a subsequent punitive expedition forced them to keep the pre-war status quo and accept a new reparations agreement. In the interbellum years, Pursat set about a rapid modernization and Occidentalization of itself with foreign advisors brought in from countries like Burgundie, Arcerion and Yonderre. From 1901-1936 the country embarked on a peaceful modernization with heavy investment from Burgundie who gradually reduced the war reparations in exchange for modernization contracts for its companies. Ancient cities were rebuilt or demolished, and entirely new cities were built along new roadway, rail, and canal infrastructure. The population of Pursat skyrocketed as medicine improved and peasant families were moved into the cities to work at new factories which reduced infant mortality rates by over 50%. During the second Great War percent and Umar dwal waged a bitter war over a series of oases that they both claimed as they expanded their rail infrastructure across the Great kivir desert. This war called the desert war in percent was part of the larger adonian campaign waged by burgundy. The seasonal nature of the combat between Prasad and Umar dual meant that fighting typically only occurred three months a year when the weather was not so hot. The nascent nature of engine and mechanical technology meant that while Umar dwal had tanks and the persatney military was fairly mechanized neither armies were able to make significant breakthroughs or maneuvers using these technologies in the shifting sands of the Great cavier. By the end of the war the border had remained mostly the same however Umar dwal had exhausted many of prasades manufacturing and financial capabilities and so it is often recorded in the history books that Prasad lost this war.

Contemporary period

After the second Great War Prasad continued its rampant modernization efforts which was widely disliked by the nomadic populations who were forcibly saddles settled in the 1950s and '60s. This led to a series of low intensity bush war conflicts in the '60s and '70s against modernization and occidentalization that compiled into the greater operation Kipling. Burgundy supported the theocratic government throughout this time and many of the previous wrongs and conflicts between the countries were settled and the two became closer and closer. Burgundy continued throughout this period to invest heavily in person both as a way to bolster the theocratic government but also as a way to build goodwill with the people. And increasing number of bringing yes companies were hiring personny employees to do much of the work, but also by investing in schools at all levels but particularly in tertiary education burgundy was investing in the creation of a professional class in Prasad which had never existed before. In the 1980s and '90s croissants standard of living increased considerably as wages rose and sustainable business ventures were transferred over to persantine ownership. They are continued to be massive migration into the cities as the information technology industry and factories became a much larger part of the personny economy. Higher paying jobs were more abundant as well as the opportunity to go to hire forms of education as well as access to health care meaning that the population was getting richer and growing faster. In the 21st century Prasad continues to become more urban and has adopted a more post-industrial economic model with services and information sectors growing exponentially between 1999 and 2028.

Government and politics

The central government of Pursat is in its capital city Mharran, home to around 4.2 million people. The government's complex known as "The Great Fort" is the ancient citadel of the city and currently hosts both branches of the government.

Executive and judicial branch

Pursat has a single branch that performs the functions of an executive and a judicial branch. The Council of Uqqāl (Aenglish: Enlightened) are a body of Druze legal and theological scholars and from among them is elected a Supreme Professor who serves as the head of state, the leader of the government, and the highest justice in the country. The Council of Uqqāl also reviews and adjudicates legal matters through a network of local Councils of Lesser Professors who also perform the functions of executive branch functionary employees.

Legislative branch

The legislative branch is a secular forum of tribal leaders whose job it is to consult with their clansmen and to draft and propose laws to the Council of Uqqāl. Its primary focus is on infrastructure, international politics, and defense over which it maintains almost complete autonomy.

Local governance

Local governance is relegated to traditional leaders, typically tribal or clan patriarchs/matriarchs in rural areas and to elected mayor-council regimes in urbanized regions. There is no intermediary form of state or provincial government as all government services are relegated to the executive branch's network of Councils of Lesser Professors.

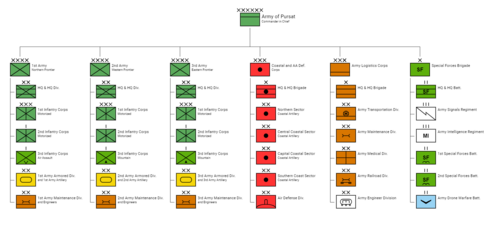

Military

Pursat as a large but underfunded, undertrained, and under-equipped military that primarily consists of the army at 1.2 million personnel, a small but professional air force of 120,000 personnel, a Littoral Defence a s Enforcement Fleet (equivalent to most nations coast guards but also with a strong defense mission) of 238,000 personnel, and a navy of 638,000 personnel. These forces suffer from a lack of centralization and have, in recent exercises conducted by Burgundie in 2018 and 2025, failed to coordinate and meet strategic objectives. The government has made considerable investments in modernizing the military but the high command is resistant to changing their ways which is impeding progress.

Because of its more liberal stance on women's rights, the Army of Pursat has, since the Islamic Revolution in Umardwal, had a contingent of Umardi women, which was formalized in 1994 as the 6th Infantry Regiment, Umardiennes (also known as the Women's Legion), of the 3rd Army, 2nd Infantry Corps. The unit is 2,740 strong and consists 70% of Umardieen, 25% Pursatnieen, and 5% other foreign nationals. The unit is used as a border guard unit on the Yanubi frontier.

-

Umardi woman in the 6th Infantry Regiment

Society

The Touareg are the largest ethnic group, comprising 38.5% of the populace. The Kemeti, primarily in the northeast of the country account for 24.6%. The Ebidi, make up 12.4%, most of them descendants of slaves brought during the colonial period. Occidentals, primarily of Bergendii descent and connected to historical colonial ties and economic partnerships, represent 9.3% of the population. The remaining 15.2% is a mix of various ethnicities. Pursi is the dominant native language, spoken by the majority. Burgoignesc is widely used in commerce, education, and government due to historical ties with Burgundie. Arabic holds significance as a liturgical language for both the Druze and Muslim faiths and is also used in local trade and cultural exchange. Druzism is the majority faith, deeply embedded in the social fabric. A significant minority practices Islam, primarily Sunni Islam, while a smaller population, mainly Occidental expatriates and converts, follow Christianity. The late 20th century saw rapid urbanization, resulting in high population density. Over 60% of the population lives in the cities, particularly in the capital city, Mharran and the coastal cities of Misherdaha, Al Darbara, Atarayya, Al Hajadad, Abu Kasna, Konyet, Senurish, Awlazig, Abu Tiyoum, and As-Sanzala.

Pursat's culture is an amalgam of native ancient Druze and Kemeti, medieval Arabic, and early-modern Occidental cultures that have layered on top of each othe over the last millennium. Druzism, the majority faith, permeates daily life with its unique rituals and beliefs, celebrated in festivals like Ziyarat al-Nabi Shu'ayb, where Druze pilgrims journey to the holy site of Nabi Shu'ayb. The Oddiyad Caliphate brought Islam and Muslim architecture and the observance of high holidays like Ramadan, during the medieval period.

Pursat's cuisine is based on Touareg staples like taguella stew. Ebidi dishes like fufu and peanut soup, brought by the colonial-era slavery network and Arabic spices and ingredients like cumin, coriander, and dates have also become regular aspects of Pursat cuisine.

Historically literature was not a major aspect of Pursatieen culture. Oral storytelling, passed down through generations of Touaregs and while they still remain an important cultural aspect of Pursatieen life, written works in Pursi, Arabic, and Burgoignesc became a part of the ouvre during the colonial-era. Pursatnieen literature often explores themes of identity, cultural preservation, and the challenges of modernization. Art in Pursat thrives with lots of government subsidization. Intricate Touareg jewelry, made of locally sourced gold and semi-precious stones are internationally recognized signs of Pursat. Attire in Pursat draws on Audonian traditionalism and Occidental modernity. Touareg men often wear the distinctive tagelmust, a blue veil that protects from the harsh desert sun, while women wear colorful headscarves and intricate silver jewelry. Ebidi women favor vibrant patterns and flowing fabrics, while men often wear dashikis or embroidered tunics. Western-style clothing is also common, particularly in urban areas.

Cuisine

Pursi cuisine

The main dishes that form Pursi cuisine are kibbeh, hummus, tabbouleh, fattoush, labneh, shawarma, mujaddara, shanklish, pastırma, sujuk and baklava. The Pursi often serve selections of appetizers, known as meze, before the main course. Za'atar, minced beef, and cheese manakish are popular hors d'œuvres. The Arabic flatbread khubz is always eaten together with meze. Drinks in Pursi culture vary, depending on the time of day and the occasion. Arabic coffee, a vestige of the Oduniyad Caliphate is the most well-known hot drink, usually prepared in the morning at breakfast or in the evening. It is usually served for guests or after food. Arak, an alcoholic drink, is a well-known beverage, served mostly on special occasions. Other Pursi beverages include ayran, jallab, white coffee, and a locally manufactured beer called Al Shark.

Kemeti cuisine

Kemeti cuisine relies heavily on legume and vegetable dishes. For most Kemetis there is a strong connection to food that is derived from ingredients that grow out of the ground as they see themselves as the Great and Ancient Agriculturalists of the region. As a result, a great number of vegetarian dishes have been developed that are the pride of the Kemeti people. Kushari (a mixture of rice, lentils, and macaroni) is the "national dish" of the Kemetis and it is served at all of the ceremonies and events of Kemeti life. It is prepared when guests are staying over, for birth, circumcisions, birthdays, weddings, and funerals. In addition, ful medames (mashed fava beans) is one of the most popular dishes. Fava bean is also used in making taʿmiya, also known as falafel, is a staple in many Darian cuisines, but originated in the culinary traditions of the Kemeti civilization. Garlic fried with coriander is added to molokhiya, a green soup made from finely chopped jute leaves, sometimes with chicken or rabbit for special occasions.

Sport

Football is the national sport of Pursat. At the highest levels, the national WAFF league soccer team of Pursat are the Pursatni Pangolins. They have never won the WAFF World Cup but they do well in the WAFF Audonian Cup most years. The country also has regional, provincial, and local leagues for professional, semi-professional, and amateur players. It is estimated that 48% of Pursatnieen play football recreationally. Pursat has sent players to every Istroyan Games since 1968. Squash and tennis are other popular sports. The Pursatni squash team has been competitive in international championships since the 1930s. Horseracing has long been a popular sport in the country, but accusations of poor treatment of horses have soured some with a more modern palate. The Pursatni fencing team has done well in international championships since the 1970s and some Pursatni fencers have been recruited to other national teams, like the Burgoignesc National Fencing Team. Pursat has done well internationally in archery and rowing with both teams medaling in the last summer Istroyan Games.

Economy

Pursat's tropical climate allows for a diverse range of agricultural activities. In the fertile lowlands, farmers cultivate like sorghum, millet, yams, sweet potatoes, cowpeas, bambara groundnut, fave beans, and bananas. Nomadic herders in the northern steppes raise livestock such as camels, goats, and sheep but due to the small scale and nomadic lifestyle these rarely make it to export markets and are consumed locally by those communities. The country possesses significant mineral resources, including copper, gold, and phosphates. Mining operations contribute to the country's export earnings and are a major employer for the country. The financial sector is rapidly evolving, with the establishment of modern banking institutions and the growth of microfinance initiatives with investments primarily coming from Burgundie. While traditional financial practices like hawala remain prevalent in some areas, the government is actively promoting financial inclusion and modernization. The manufacturing sector is primarily focused on the assembly of electronics, particularly microprocessors and cellphones. This industry has benefited from foreign investment, primarily from Burgundie, and technology transfer, contributing to the country's economic growth and diversification. The government of Pursat hosts workshops for native skilled artisans to produce intricate textiles (rugs, wool, and tanned leather), traditional pottery (tagines in particular), jewelry, and camel and goat leather goods, which are sought after by both domestic and international consumers. Pursat's government is working with domestic and international companies to invest in tourism infrastructure that will lean into the purported Biblical connections and become a hotspot for Christian pilgrims and religious tourism. Pursat's coastline offers abundant fishing opportunities, supporting both local fishing communities and a growing aquaculture industry. Deep-sea fishing vessels primarily catch tuna and other pelagic fish, while coastal communities engage in artisanal fishing practices. Aquaculture farms, particularly shrimp farms, have emerged as a significant contributor to seafood exports. As global awareness of environmental issues grows, Pursat is actively developing its green sector. Investments in renewable energy sources like solar and wind power are reducing the country's reliance on fossil fuels, but these efforts are still nascent.

Manufacturing

The manufacturing sector in Pursat is predominantly based around the processing and product making of natural products for export. Ropework remains a key manufacturing industry, with a significant portion of the world's natural fiber rope made in Pursat. The phosphates mined in the country are processed into feed phosphates, fertilizer, fluoride glass, and detergents. There is also a significant number of fractal distillation and chemical plants across the country that produce noble gases (particularly helium (He), neon (Ne), argon (Ar), krypton (Kr), and xenon (Xe)) which are sold to industrial firms around the world.

Bennu et Nuit

The Burgoignesc company Jean fils et Jean fils has a partnership with Bennu et Nuit, a chain of factory farms in Pursat that grow and harvest papyrus as a sustainable product that is uses for a number of its products. Once of their products, the Papyrus sanitary pad, has been credited as a major breakthrough for women in Daria. The papyrus sanitary pad has helped make sanitary pads an affordable and accessible necessity for young girls in developing countries. They help tackle the problem of girls' absenteeism in school owing to menstruation and associated behaviors for which they do not have adequate facilities (for example: lack of privacy for cleaning, poor availability of pads, lack of education about menstrual hygiene, lack of separate toilet facilities, and lack of access to water). Since starting its partnership, Bennu et Nuit has increased production and output from 7,000 sanitary pads a month to 85,400 pads a month which use the Burgoignesc trade networks to sell their products all across Daria.

Direct Cordage of Pursat

Direct Cordage of Pursat is a multinational natural fiber rope manufacturer based in Clysvatjer, Pursat. It owns farms and manufactories across Daria and produces 550,000 tonnes of natural fiber rope each year and employs 84,030 people, 14,390 of them in Pursat. They manufacture rope and line in sisal, coir, jute, manila, and papyrus, but their papyrus cordage is their flagship product. They are also in a partnership with Estia-Odoneru Gypsum, Salt, and Aggregate to make fibers for the latter's fiber-reinforced concrete.

Recycling and waste management

Ship breaking

One of the largest industries by value and by population involvement in Pursat is ship breaking. There are 8 ship breaking yards along the mainland and 3 along the island of Fapimunein. The yards on the mainland are bigger and designed to serve the needs of Pursats' Occidental clientele who typically have large numbers of bigger ships. The yards on Fapimunein serve clients from Audonia and have a much lower through rate. These yards are primarily focused on scrapping the ships but the steel in particular is recycled and provides over 100% of the annual need for steel in the country. The excess steel is sold to neighboring countries and has been praised with reducing the demand for mined iron ore and reduces energy use in the steelmaking process across southern Daria. Fixtures and other maritime equipment that is salvageable is sold to regional shipyards for reuse as well. As such, ships produced in Daria often have very high capabilities and facilities on board even if the equipment is a bit dated.

Infrastructure

Air

Pursat has three international airports the Mharran International Airport in metro Mharran, the Al Baribi International Airport both serving the capital region. The other is Awlazig International Airport that serves the northwestern provinces.

| Name | Location | Type | Brief description | Code(s) | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mharran International Airport | Passenger and cargo | 24/7/365 air traffic control operations, 3x runways, capable of receiving all airframes, cargo terminal, passenger terminal, complete maintenance facilities, integrated customs and border control service | ATRO: AMP

ICAO: AMPT |

TBD | |

| Al Baribi International Airport | Passenger and cargo | 24/7/365 air traffic control operations, 2x runways, capable of receiving all airframes, cargo terminal, passenger terminal, complete maintenance facilities, integrated customs and border control service | ATRO: ABP

ICAO: ABPT |

TBD | |

| Awlazig International Airport | Passenger and cargo | 24/7/365 air traffic control operations, 3x runways, capable of receiving all airframes, cargo terminal, passenger terminal, complete maintenance facilities, integrated customs and border control service | ATRO: AWP

ICAO: AWPT |

TBD |

Rail

Pursat uses Standard gauge, 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) as most of its rail infrastructure has been under the auspices of Burgundie and its sphere of influence in the Middle seas region, who all use that rail gauge. The country has a strong rail network with 13,669km of rail, 1,560km of which is electrified, and 7,589km is double track. The Agency for Rail Safety is the regulating body of the rails and the rails are owned almost exclusively by the government. Carriers for both freight and passengers rent access on the lines on a fee-for-service model. This has led to freight haulers to prioritize extremely long trains to reduce the fees they have to pay, which has become a standard practice and expectation. Motorists, both personal and truck traffic have lodged complaints to either invest in non-grade crossings, or to regulate train length.

Roads

National highways face the constant battle against harsh desert conditions and resource limitations. Secondary gravel roads serve smaller towns and communities but succumb to seasonal flooding. These unpaved local roads provide crucial last-mile connectivity, yet navigating them, especially during rains, can be hazardous. A major contract has been signed with Estia-Odoneru Gypsum, Salt, and Aggregate and O'Shea Industrial Services to improve existing roadways and bridges, as well as to extend the paved infrastructure to many municipalities in the interior. The contract started in 2028 and is ongoing with O'Shea Industrial Services promoting an increasing number of Pursatni project managers and engineers that they trained. These are expected to become a new class of roadway, drainage, and structural engineering professionals that will create a new cadre of experts mirroring the Grand Corps of Civil Engineers of the Nation of Burgundie.

Louage

A louage is a minibus shared taxi in many parts of Daria that were colonized by Burgundie. In Burgoignesc, the name means "rental." Departing only when filled with passengers not at specific times, they can be hired at stations. Louage ply set routes, and fares are set by the government. In contrast to other share taxis in Audonia, louage are sparsely decorated. Louages use a color-coding system to show customers what type of transport they provide and the destination of the vehicle. Louages with red lettering travel from one state to another, blue travel from city to city within a state, and yellow serves rural locales. Fares are purchased from ticket agents who walk throughout the louage stations or stands. Typical vehicles include: the MILCAR Jornalero, the TerreRaubeuer Valliant 130, and the CTC M237-07.

Power and electricity

-

Muzeyah Nuclear Power Station

Pursat is still mostly reliant on burning fossil fuels for power, but it does have one active nuclear power plant, the Muzeyah Nuclear Power Station (Gen II+) which generates 1000MWe which was built in 1989. There are two more nuclear powerplants in development which will have generation IV reactors and are estimated to have a combined output of almost 4,000MWe. Since the 1990s the country has been investing in sustainable energy types with the first solar tower coming online in 2003 and the first wind farm coming online in 2005. These projects were deemed feasible and now the country generates 18% of its power needs from renewables. There are 17 new wind farms planned from the rest of the country and 8 more solar farms. Despite the abundant sun, the technology of solar is still not durable against the endemic sand in the country and further research is being done.

See also