Istroya Oriental colony: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

||

| (12 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 71: | Line 71: | ||

|}} | |}} | ||

Istroya Oriental Colony was a colonial holding administered by the [[Burgoignesc South Levantine Trading Company|Bourgondii Royal Trading Company (BRTC)]] on the western coast of the [[Audonia]]n region of [[Daria]] from [[1577]] until [[1795]] at which point the [[Kandara#Great_Rebellion_of_Slavery_Bay|Great Rebellion of Slavery Bay]] overwhelmed the colony forcing its end and the expulsion of the [[Occidental]]s living within it. | Istroya Oriental Colony was a colonial holding of the [[Duchy of Bourgondi]] administered by the [[Burgoignesc South Levantine Trading Company|Bourgondii Royal Trading Company (BRTC)]] on the western coast of the [[Audonia]]n region of [[Daria]] from [[1577]] until [[1795]] at which point the [[Kandara#Great_Rebellion_of_Slavery_Bay|Great Rebellion of Slavery Bay]] overwhelmed the colony forcing its end and the expulsion of the [[Occidental]]s living within it. | ||

==Colonial administration== | |||

===Early administration=== | |||

The first Audienciæ della Colonie Istroya Oriental was established shortly after the [[1577]] founding, consisted of a [[Bourgondii Royal Trading Company|BRTC]]-appointed magistrate and elected congregational elders. It served as the colony’s highest court, applying Burgoignesc law while considering the unique circumstances and values of the [[Phariseedom|Pharisee]] settlers. The Audienciæ resolved disputes, ensuring religious freedom, and maintaining order. Beyond its judicial functions, the Audienciæ played a vital role in colonial administration. It advised the BRTC’s appointed governor on policy, managed colonial resources, and collaborated with local congregations and [[patroon]]s to create local laws. Early Istroya Oriental focused on establishing settlements, developing agriculture, and establishing trade relationships with indigenous [[Battganuur]]is. The Audienciæ oversaw land distribution, regulated trade, and managed relations with local tribes. This period saw the growth of key settlements along the coast and the development of plantation agriculture. | |||

As Istroya Oriental expanded, attracting more settlers and intensifying agricultural production, the Audienciæ system faced increasing challenges. The growing complexity of colonial society, coupled with the BRTC’s desire for tighter control over colonial affairs, created tension. The Audienciæ's decentralized structure struggled to manage the expanding colony’s administrative and judicial demands. By the 1620s, the BRTC began to exert increasing influence over the Audienciæ's decisions, limiting its autonomy. This tension continued into the 1630s, with the BRTC gradually appointing a viceroy. | |||

===Viceroyalty=== | |||

The appointment of a viceroy in [[1637]] resulted from the [[Duchy of Bourgondi]]'s rapidly expanding colonial empire, increased intercolonial warfare, conflicts with rival colonial powers like Kiravia on the high seas, and the desire for colonial self-sufficiency and profitability. Centralizing authority under direct BRTC control via a viceroy in each colony, including Istroya Oriental, gave the Duke greater military control and enhanced financial and military strategy. The viceroy held supreme executive, legislative, and judicial power, streamlining colonial administration and implementing BRTC policies. This facilitated more efficient resource extraction and management, particularly within the expanding plantation economy. However, it diminished the Audienciæ’s previous local autonomy, creating friction with colonists. The viceroys focused on colonial expansion, increased agricultural output primarily through enslaved labor, and strengthened the BRTC’s economic dominance. This period saw large latifundii consolidate and the slave trade grow. As the colony expanded throughout the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the viceroy’s responsibilities increased significantly. Managing the vast territory, complex economy, and diverse population became unsustainable for a single individual. In [[1761]], the viceroyalty was replaced by presidencies, each governing a distinct region of Istroya Oriental and reporting to a newly established colonial council. | |||

List of Viceroys: | |||

* Guilhem-Piere Andrieu de Tolosie ([[1637]]-[[1652]]) | |||

* Raimon-Jausep Frances de Montpelhier ([[1652]]-[[1668]]) | |||

* Bertrand-Piere Jacmenon Carcasseu ([[1668]]-[[1685]]) | |||

* Folquet-Andrieu Raimon de Narbone ([[1685]]-[[1701]]) | |||

* Isarn-Joan Bernat d'Avinhon ([[1701]]-[[1718]]) | |||

* Aimeric-Bernat Raimon d'Ais ([[1718]]-[[1735]]) | |||

* Uc-Peire Anton Bordeu ([[1735]]-[[1752]]) | |||

* Jaufre-Raimon Bernat de Peiregord ([[1752]]-[[1761]]) | |||

====Frontier rebellions==== | |||

[[File:Marie-Gabriel-Florent-Auguste,_comte_de_Choiseul-Gouffier.jpg|right|thumb|Jaufre-Raimon Bernat de Peiregord, last colonial viceroy.]] | |||

As the colony expanded into the interior, the viceroy’s perceived neglect of interior regions, simmered throughout the 1740s and 1750s. He focused on the coastal plantation economy and BRTC interests and was seen as unresponsive to the unique challenges of the frontier settlements. Primary among these concerns where indigenous conflicts, limited access to markets and resources, and inadequate representation. This bred resentment and alienation and led to localized uprisings and protests ensued, with frontier communities demanding greater autonomy, improved resource access, protection from raids, and reduced viceregal authority. These actions ranged from peaceful petitions to armed resistance against BRTC forces who came to suppress them. The viceroy’s attempts at forceful suppression proved ineffective due to the vast territory and limited resources. By the late 1750s, the coordinated nature of some uprisings signaled growing frontier unity. Recognizing the instability and economic threat, the Duke met with the BRTC and forced them to began considering governance reforms. These rebellions, coupled with the expanding colony’s administrative burden, led to the dissolution of the viceroyalty and the establishment of the presidency system in [[1761]]. | |||

===Presidencies=== | |||

The dissolution of the viceroyalty in [[1761]], under pressure from the Duke, resulted in the creation of nine presidencies: Chaukhira, Eshel, Malarand, Kavir, Asakhs, Oros, Tafraout, Chefchaouen, and Bulkhawan. Each presidency was headed by a Governor-presiding, a semi-elected governor. Three candidates are elected by a single transferable vote election held every 5 years; the three candidates are presented to the BTRC, which chooses from among them the next Governor-presiding over each presidency. This system is still used today in the [[BORA]] provinces. The Governor-presiding held executive and judicial authority within their respective territory. This decentralization of power addressed the frontier regions’ grievances by granting them greater local autonomy. The newly formed Presidency Council provided a central governing body. This council comprised the nine presidents, representatives from the BRTC, and a representative of the Duke. The Presidency Council held legislative authority; enacting laws applicable to the entire colony. Each presidency also maintained its own colonial assembly, called Congregations of the Law of Man, which could legislate on local matters. The frontier presidencies, for example, focused on managing relations with indigenous populations, promoting settlement, and developing infrastructure. The coastal presidencies, with their established plantation economies, concentrated on regulating trade, managing port cities, and overseeing agricultural production. This regional focus allowed for more effective and representative governance. | |||

==Gallery== | |||

{|style="margin: 0 auto;" | {|style="margin: 0 auto;" | ||

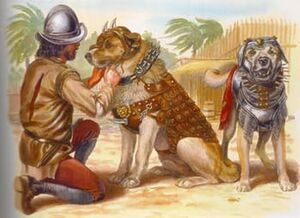

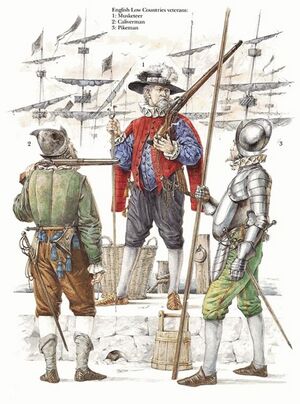

|[[File:Burg Colonial cynophile infantry 1583.jpg|thumb|Martillien Colonial cynophile infantry]] | |[[File:Burg Colonial cynophile infantry 1583.jpg|thumb|Martillien Colonial cynophile infantry]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:26, 11 January 2025

| This article is a stub. You can help IxWiki by expanding it. |

Istroya Oriental Colony Colonie Istroya Orientale | |

|---|---|

| 1611-1795 | |

|

Flag | |

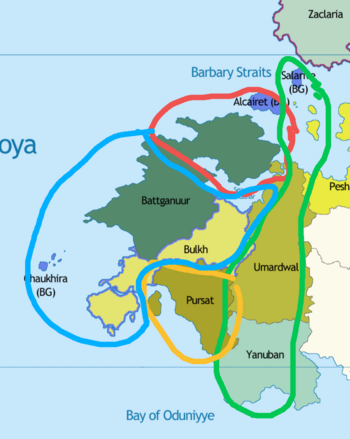

Istroya Oriental Colony in blue Kandahari-Pukhtun colony in green Eloillette in gold Barbary Straits colony in red | |

| Status | Colony of the Duchy of Bourgondi |

| Official language | Burgoignesc |

| Religion | Calvinism/Congregational church, Presbyterianism |

| Government | Constitutional monarchy |

| Governor Epistates | |

| Historical era | Age of Discovery, Age of Sail |

• Established | 1577 |

• Disestablished | 1795 |

| Today part of | Battganuur Bulkh Chaukhira |

Istroya Oriental Colony was a colonial holding of the Duchy of Bourgondi administered by the Bourgondii Royal Trading Company (BRTC) on the western coast of the Audonian region of Daria from 1577 until 1795 at which point the Great Rebellion of Slavery Bay overwhelmed the colony forcing its end and the expulsion of the Occidentals living within it.

Colonial administration

Early administration

The first Audienciæ della Colonie Istroya Oriental was established shortly after the 1577 founding, consisted of a BRTC-appointed magistrate and elected congregational elders. It served as the colony’s highest court, applying Burgoignesc law while considering the unique circumstances and values of the Pharisee settlers. The Audienciæ resolved disputes, ensuring religious freedom, and maintaining order. Beyond its judicial functions, the Audienciæ played a vital role in colonial administration. It advised the BRTC’s appointed governor on policy, managed colonial resources, and collaborated with local congregations and patroons to create local laws. Early Istroya Oriental focused on establishing settlements, developing agriculture, and establishing trade relationships with indigenous Battganuuris. The Audienciæ oversaw land distribution, regulated trade, and managed relations with local tribes. This period saw the growth of key settlements along the coast and the development of plantation agriculture. As Istroya Oriental expanded, attracting more settlers and intensifying agricultural production, the Audienciæ system faced increasing challenges. The growing complexity of colonial society, coupled with the BRTC’s desire for tighter control over colonial affairs, created tension. The Audienciæ's decentralized structure struggled to manage the expanding colony’s administrative and judicial demands. By the 1620s, the BRTC began to exert increasing influence over the Audienciæ's decisions, limiting its autonomy. This tension continued into the 1630s, with the BRTC gradually appointing a viceroy.

Viceroyalty

The appointment of a viceroy in 1637 resulted from the Duchy of Bourgondi's rapidly expanding colonial empire, increased intercolonial warfare, conflicts with rival colonial powers like Kiravia on the high seas, and the desire for colonial self-sufficiency and profitability. Centralizing authority under direct BRTC control via a viceroy in each colony, including Istroya Oriental, gave the Duke greater military control and enhanced financial and military strategy. The viceroy held supreme executive, legislative, and judicial power, streamlining colonial administration and implementing BRTC policies. This facilitated more efficient resource extraction and management, particularly within the expanding plantation economy. However, it diminished the Audienciæ’s previous local autonomy, creating friction with colonists. The viceroys focused on colonial expansion, increased agricultural output primarily through enslaved labor, and strengthened the BRTC’s economic dominance. This period saw large latifundii consolidate and the slave trade grow. As the colony expanded throughout the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the viceroy’s responsibilities increased significantly. Managing the vast territory, complex economy, and diverse population became unsustainable for a single individual. In 1761, the viceroyalty was replaced by presidencies, each governing a distinct region of Istroya Oriental and reporting to a newly established colonial council.

List of Viceroys:

- Guilhem-Piere Andrieu de Tolosie (1637-1652)

- Raimon-Jausep Frances de Montpelhier (1652-1668)

- Bertrand-Piere Jacmenon Carcasseu (1668-1685)

- Folquet-Andrieu Raimon de Narbone (1685-1701)

- Isarn-Joan Bernat d'Avinhon (1701-1718)

- Aimeric-Bernat Raimon d'Ais (1718-1735)

- Uc-Peire Anton Bordeu (1735-1752)

- Jaufre-Raimon Bernat de Peiregord (1752-1761)

Frontier rebellions

As the colony expanded into the interior, the viceroy’s perceived neglect of interior regions, simmered throughout the 1740s and 1750s. He focused on the coastal plantation economy and BRTC interests and was seen as unresponsive to the unique challenges of the frontier settlements. Primary among these concerns where indigenous conflicts, limited access to markets and resources, and inadequate representation. This bred resentment and alienation and led to localized uprisings and protests ensued, with frontier communities demanding greater autonomy, improved resource access, protection from raids, and reduced viceregal authority. These actions ranged from peaceful petitions to armed resistance against BRTC forces who came to suppress them. The viceroy’s attempts at forceful suppression proved ineffective due to the vast territory and limited resources. By the late 1750s, the coordinated nature of some uprisings signaled growing frontier unity. Recognizing the instability and economic threat, the Duke met with the BRTC and forced them to began considering governance reforms. These rebellions, coupled with the expanding colony’s administrative burden, led to the dissolution of the viceroyalty and the establishment of the presidency system in 1761.

Presidencies

The dissolution of the viceroyalty in 1761, under pressure from the Duke, resulted in the creation of nine presidencies: Chaukhira, Eshel, Malarand, Kavir, Asakhs, Oros, Tafraout, Chefchaouen, and Bulkhawan. Each presidency was headed by a Governor-presiding, a semi-elected governor. Three candidates are elected by a single transferable vote election held every 5 years; the three candidates are presented to the BTRC, which chooses from among them the next Governor-presiding over each presidency. This system is still used today in the BORA provinces. The Governor-presiding held executive and judicial authority within their respective territory. This decentralization of power addressed the frontier regions’ grievances by granting them greater local autonomy. The newly formed Presidency Council provided a central governing body. This council comprised the nine presidents, representatives from the BRTC, and a representative of the Duke. The Presidency Council held legislative authority; enacting laws applicable to the entire colony. Each presidency also maintained its own colonial assembly, called Congregations of the Law of Man, which could legislate on local matters. The frontier presidencies, for example, focused on managing relations with indigenous populations, promoting settlement, and developing infrastructure. The coastal presidencies, with their established plantation economies, concentrated on regulating trade, managing port cities, and overseeing agricultural production. This regional focus allowed for more effective and representative governance.

Gallery

|

|

|

|

|