New Burgundie Colony: Difference between revisions

Created page with "{| class="wikitable" ! colspan="2" |Neu Burgund |- | colspan="2" |1635–1933 |- | colspan="2" |Error creating thumbnail: File missing Flag |- | colspan="2" |Error creating t..." Tag: 2017 source edit |

Tag: 2017 source edit |

||

| (20 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{| | {{wip}} | ||

{{Infobox former country | |||

| | | conventional_long_name = New Burgundie Colony | ||

| | | native_name = Colonie de Nouvelle Bourgondi | ||

| | | common_name = | ||

| | | life_span = [[1598]] until [[1873]] | ||

| status = {{wp|Charter colony}} of the [[Burgoignesc South Levantine Trading Company|BRTC]] | |||

Flag | | empire = [[History_of_Burgundie#Duchy_of_Bourgondi|Duchy of Bourgondi]] | ||

| | | image_flag = BourgondiFlag.png | ||

| | | flag_type_article = Flag of New Burgundie | ||

| | | flag_size = | ||

| image_coat = | |||

| | | coa_size = | ||

| symbol_type = | |||

| royal_anthem = | |||

| image_map = File:New Burg colonial claims expansion map.jpg | |||

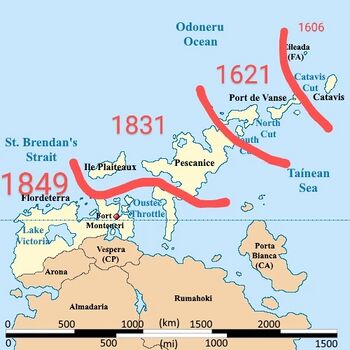

| | | image_map_caption = Expansion of New Burgundie Colony | ||

| | | capital = | ||

*Babagne <small>([[1598]]-[[1619]])</small> | |||

| | *Aurifort <small>([[1619]]-[[1752]])</small> | ||

| | *Carcaleme <small>([[1752]]-[[1860]])</small> | ||

*Fort Monteneri <small>([[1860]]-[[1873]])</small> | |||

| | | languages_type = {{nowr|Official language}} | ||

|- | | languages = [[Burgoignesc language|Burgoignesc]] | ||

| languages2_sub = yes | |||

| | | languages2_type = {{nowr|Common languages}} | ||

| | | languages2 = [[Julian Ænglish]], [[Lebhan language|Lebhan]], {{wpl|Latin}} | ||

| religion = [[Mercantile Reform Protestantism]], [[Catholic Church]], {{wp|Presbyterianism}}, | |||

| | | legislature = | ||

| | | upper_house = | ||

| lower_house = | |||

| government_type = {{nowr|[[Constitutional monarchy]]}} | |||

| title_leader = | |||

| leader1 = | |||

| leader2 = | |||

| year_leader1 = | |||

| year_leader2 = | |||

| title_representative = {{wpl|Governor}}-{{wpl|Epistates}} | |||

| representative1 = | |||

| representative2 = | |||

| year_representative1 = | |||

| year_representative2 = | |||

| title_deputy = | |||

| deputy1 = | |||

| year_deputy1 = | |||

| era = {{wpl|Age of Discovery}}, {{wpl|Age of Sail}} | |||

| date_start = | |||

| year_start = [[1598]] | |||

| event1 = | |||

| date_event1 = | |||

| event2 = | |||

| date_event2 = | |||

| event3 = | |||

| date_event3 = | |||

| event4 = | |||

| date_event4 = | |||

| event_end = Loss of the [[New Burgundie Sucession War]] | |||

| date_end = | |||

| year_end = [[1873]] | |||

| stat_year1 = | |||

| stat_pop1 = | |||

| p1 = Oduniyyad Caliphate | |||

| s1 = | |||

| flag_p1 = | |||

| flag_s1 = | |||

| today = [[Equatorial Ostiecia]] | |||

| footnotes = | |||

| demonym = | |||

| area_km2 = | |||

| area_rank = | |||

| GDP_PPP = | |||

| GDP_PPP_year = | |||

| HDI = | |||

| HDI_year = | |||

| | | | ||

|}} | |||

The [[New Burgundie Colony]], resulting from the [[Expulsion of the Protestants]] refugees fleeing [[Dragonnades]] and upheaval in the [[Levantia]], was established in [[1598]]. Chartered by the [[Duchy of Bourgondi]], the colony served as both a sanctuary for the Protestants and an economic venture for the [[Duchy of Bourgondi|Duchy]]. The early years of the colony were fraught with challenges, not least of which were the constant threats posed by entrenched pirate factions, most notably the [[Kingdom of Oustec]]. However, the colonists, hardened by their experiences in the [[Great Confessional War]] and united by their shared faith, proved resilient. Through a combination of defensive fortifications, astute diplomacy, and strategic naval engagements, they gradually established their dominance over the northern [[Capelranco Archipelago]]. This was achieved not through brute force alone, but through a shrewd understanding of local power dynamics and a willingness to forge alliances with indigenous [[Latinic|Latino]]-{{wp|Polynesian}} groups who shared a common interest in curbing the pirates' reign of terror. | |||

The [[New Burgundie Colony|colony's]] strategic location along major trade routes, combined with the development of its agricultural and manufacturing sectors, attracted a steady influx of merchants, artisans, and skilled laborers from [[Crona]], [[Srpedon]], and later [[Audonia]]. The colony's fertile volcanic soil proved ideal for cultivating lucrative cash crops such as {{wp|sugar cane}} {{wp|coffee}}, and spices, while its burgeoning shipbuilding industry capitalized on the abundant tropical timber resources and the growing demand for maritime transport. {{New Burgundie}}'s merchant fleet became renowned for its speed and efficiency, as it plied the trade routes between [[Vallos]], [[Crona]], and the burgeoning [[Maritime Dericania]]n [[Burgoignesc colonial empire| colonies]] of [[Audonia]]. This economic prosperity, coupled with the colony's unique socio-political structure – a blend of Calvinist piety, communal solidarity, and nascent democratic ideals – attracted a diverse population of immigrants seeking economic opportunity and religious freedom. | |||

The [[New Burgundie Colony|colony's]] economic success was mirrored by its increasing military prowess. By [[1621]], [[New Burgundie]] had effectively neutralized the pirate threat, asserting its dominance over the northern [[Capelranco Archipelago]] and securing its trade routes in [[St. Brendan's Strait]]. This victory opened up new avenues for economic expansion and solidified the colony's position as a regional power. In the decades that followed, [[New Burgundie]] evolved into a vibrant and prosperous colony, its economy diversified and its society increasingly cosmopolitan. The influx of [[Bergendii]] refugees from [[Audonia]] in the early 19th century, fleeing the collapse of the [[Audonia]]n colonies, brought a new wave of challenges and opportunities. The [[New Burgundie Colony|colony's]] population skyrocketed, leading to rapid urbanization and the industrialization of agriculture. However, this demographic shift also brought new skills, ideas, and entrepreneurial spirit to [[New Burgundie]], further fueling its economic growth. | |||

The colony's lack of entrenched traditional structures allowed it to quickly adapt to the technological advancements of the {{wp|Industrial Revolution}}, surpassing even the [[Burgoignesc Metropole]] in some areas. This era of rapid change solidified the values of self-reliance, innovation, and a frontier mentality that continue to permeate Equitorioise culture today, encapsulated in the concepts of "{{wp|Yankee ingenuity|Equitorioise ingenuity}}" and "{{wp|Yankee stoicism|Equitorioise stoicism}}." | |||

The [[Odurian War]] of [[1858]]-[[1859]], sparked by [[Caphiria]]'s intervention in the rump state of the [[Kingdom of Oustec]], saw [[New Burgundie]] and its metropole, now the [[History_of_Burgundie#Burgundie-Faramount_Union|Burgundie-Faramount Union]], drawn into a conflict that ultimately resulted in the partition of [[Oustec]] and the annexation of the northern territories into the growing Burgoignesc realm, now known as [[Flordeterre]]. This conflict, while devastating, further solidified [[New Burgundie]]'s strategic importance and its role as a regional contender. | |||

The aftermath of the [[Odurian War]] set the stage for the [[New Burgundie Secession War]] of [[1870]]-[[1873]]. Fueled by a complex interplay of socio-economic grievances, political aspirations, and a burgeoning sense of national identity, the colonists rose in rebellion against their [[Burgundie|Burgoignesc overlords]]. Despite their eventual defeat, the war marked a turning point in the colony's history. The recognition of [[New Burgundie]] as a home rule constituent country within [[The Burgundies]] was a significant concession, paving the way for the emergence of modern Equatorial Ostiecia. | |||

==See also== | |||

*[[History of Burgundie]] | |||

*[[Burgoignesc colonial empire]] | |||

*[[Duchy of Bourgondi]] | |||

{{Colonies of Burgundie}} | |||

{{Burgundie NavBox}} | |||

{{Vallos topics}} | |||

[[Category:IXWB]] | |||

[[Category:History of Burgundie]] | |||

[[Category:Colonial History of Burgundie]] | |||

|} | |||

== | |||

[[Category:Burgundie]] | |||

Latest revision as of 11:35, 29 June 2024

This article is a work-in-progress because it is incomplete and pending further input from an author. Note: The contents of this article are not considered canonical and may be inaccurate. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. |

New Burgundie Colony Colonie de Nouvelle Bourgondi | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1598 until 1873 | |||||||

|

Flag | |||||||

Expansion of New Burgundie Colony | |||||||

| Status | Charter colony of the BRTC | ||||||

| Capital | |||||||

| Official language | Burgoignesc | ||||||

Common languages | Julian Ænglish, Lebhan, Latin | ||||||

| Religion | Mercantile Reform Protestantism, Catholic Church, Presbyterianism, | ||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||||

| Governor-Epistates | |||||||

| Historical era | Age of Discovery, Age of Sail | ||||||

• Established | 1598 | ||||||

• Loss of the New Burgundie Sucession War | 1873 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Today part of | Equatorial Ostiecia | ||||||

The New Burgundie Colony, resulting from the Expulsion of the Protestants refugees fleeing Dragonnades and upheaval in the Levantia, was established in 1598. Chartered by the Duchy of Bourgondi, the colony served as both a sanctuary for the Protestants and an economic venture for the Duchy. The early years of the colony were fraught with challenges, not least of which were the constant threats posed by entrenched pirate factions, most notably the Kingdom of Oustec. However, the colonists, hardened by their experiences in the Great Confessional War and united by their shared faith, proved resilient. Through a combination of defensive fortifications, astute diplomacy, and strategic naval engagements, they gradually established their dominance over the northern Capelranco Archipelago. This was achieved not through brute force alone, but through a shrewd understanding of local power dynamics and a willingness to forge alliances with indigenous Latino-Polynesian groups who shared a common interest in curbing the pirates' reign of terror. The colony's strategic location along major trade routes, combined with the development of its agricultural and manufacturing sectors, attracted a steady influx of merchants, artisans, and skilled laborers from Crona, Srpedon, and later Audonia. The colony's fertile volcanic soil proved ideal for cultivating lucrative cash crops such as sugar cane coffee, and spices, while its burgeoning shipbuilding industry capitalized on the abundant tropical timber resources and the growing demand for maritime transport. Template:New Burgundie's merchant fleet became renowned for its speed and efficiency, as it plied the trade routes between Vallos, Crona, and the burgeoning Maritime Dericanian colonies of Audonia. This economic prosperity, coupled with the colony's unique socio-political structure – a blend of Calvinist piety, communal solidarity, and nascent democratic ideals – attracted a diverse population of immigrants seeking economic opportunity and religious freedom. The colony's economic success was mirrored by its increasing military prowess. By 1621, New Burgundie had effectively neutralized the pirate threat, asserting its dominance over the northern Capelranco Archipelago and securing its trade routes in St. Brendan's Strait. This victory opened up new avenues for economic expansion and solidified the colony's position as a regional power. In the decades that followed, New Burgundie evolved into a vibrant and prosperous colony, its economy diversified and its society increasingly cosmopolitan. The influx of Bergendii refugees from Audonia in the early 19th century, fleeing the collapse of the Audonian colonies, brought a new wave of challenges and opportunities. The colony's population skyrocketed, leading to rapid urbanization and the industrialization of agriculture. However, this demographic shift also brought new skills, ideas, and entrepreneurial spirit to New Burgundie, further fueling its economic growth. The colony's lack of entrenched traditional structures allowed it to quickly adapt to the technological advancements of the Industrial Revolution, surpassing even the Burgoignesc Metropole in some areas. This era of rapid change solidified the values of self-reliance, innovation, and a frontier mentality that continue to permeate Equitorioise culture today, encapsulated in the concepts of "Equitorioise ingenuity" and "Equitorioise stoicism." The Odurian War of 1858-1859, sparked by Caphiria's intervention in the rump state of the Kingdom of Oustec, saw New Burgundie and its metropole, now the Burgundie-Faramount Union, drawn into a conflict that ultimately resulted in the partition of Oustec and the annexation of the northern territories into the growing Burgoignesc realm, now known as Flordeterre. This conflict, while devastating, further solidified New Burgundie's strategic importance and its role as a regional contender. The aftermath of the Odurian War set the stage for the New Burgundie Secession War of 1870-1873. Fueled by a complex interplay of socio-economic grievances, political aspirations, and a burgeoning sense of national identity, the colonists rose in rebellion against their Burgoignesc overlords. Despite their eventual defeat, the war marked a turning point in the colony's history. The recognition of New Burgundie as a home rule constituent country within The Burgundies was a significant concession, paving the way for the emergence of modern Equatorial Ostiecia.