Chaukhira

This article is a work-in-progress because it is incomplete and pending further input from an author. Note: The contents of this article are not considered canonical and may be inaccurate. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. |

Script error: The module returned a nil value. It is supposed to return an export table.

Trade Island of Chaukira

Chaukhira | |

|---|---|

Abu-Ouncanobi from the air | |

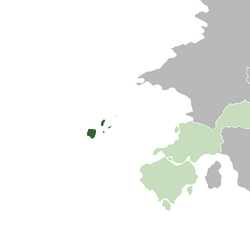

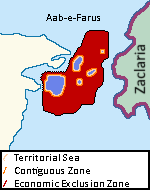

Location of the Burgoignesc province of Chaukhira Off the coast of Audonia (gray) Bulkh, in real union with Burgundie (light green) | |

| Nation | |

| Constituent Country equivalent | Burgoignesc Overseas Territory Assembly |

| Geographic Designation | Audonio-Alshari Burgundie |

| Capital | Abu-Ouncanobi |

| Government | |

| • Governor-Epistates | Marcel-Anwar bin Qadafim |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9,090.858 km2 (3,510.000 sq mi) |

| Population (2030) | |

| • Total | 1,254,493 |

| • Density | 140/km2 (360/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Chaukhiroise |

Etymology

Romanization of Shah (king) kheera (cucumber), approximately the cucumber kingdom.

Geography

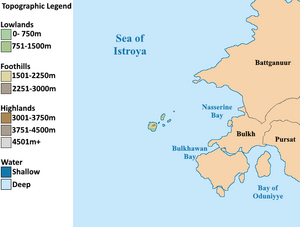

The largest and most western island is called Chaukhira Maior (the small island off of it's northeastern coast is called Chaukhira Minor and is hardly referenced uniquely). The second largest, to the northeast is Taizerbo, the smallest to the extreme northeast is Taoulga, coming back to the southwest is Ghat, and in the center of the island cluster is Akhdaran.

Climate

Chaukhira has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) with "warm, sometimes hot" summers and "generally mild", to "cool" winters. The El Niño–Southern Oscillation, the Sea of Istroya Dipole and the Southern Annular Mode play an important role in determining Chaukhira's weather patterns: drought and bushfire on the one hand, and storms and flooding on the other. The weather is moderated by proximity to the ocean.

Extreme temperatures have ranged from 45.8 °C (114.4 °F) on 18 January 2013 to 2.1 °C (35.8 °F) on 22 June 1932. An average of 14.9 days a year have temperatures at or above 30 °C (86 °F). The hottest day on the islands occurred on 4 January 2020, where a high of 48.9 °C (120.0 °F) was recorded. The average annual temperature of the sea ranges from 18.5 °C (65.3 °F) in September to 23.7 °C (74.7 °F) in February. Chaukhira has an average of 7.2 hours of sunshine per day and 109.5 clear days annually. Frost is recorded early in the morning a few times in winter. Autumn and spring are the transitional seasons, with spring showing a larger temperature variation than autumn.

| Climate data for Chaukhira | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 46.4 (115.5) |

42.9 (109.2) |

41.2 (106.2) |

35.7 (96.3) |

29.1 (84.4) |

25.6 (78.1) |

26.7 (80.1) |

30.9 (87.6) |

35.9 (96.6) |

39.1 (102.4) |

43.4 (110.1) |

43.5 (110.3) |

46.4 (115.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 27.7 (81.9) |

27.1 (80.8) |

25.8 (78.4) |

23.3 (73.9) |

20.6 (69.1) |

18.1 (64.6) |

17.7 (63.9) |

19.1 (66.4) |

21.6 (70.9) |

23.6 (74.5) |

24.6 (76.3) |

26.4 (79.5) |

23.0 (73.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 20.0 (68.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

18.5 (65.3) |

15.2 (59.4) |

12.1 (53.8) |

9.8 (49.6) |

8.5 (47.3) |

9.3 (48.7) |

11.9 (53.4) |

14.4 (57.9) |

16.5 (61.7) |

18.4 (65.1) |

14.5 (58.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 13.0 (55.4) |

12.0 (53.6) |

8.8 (47.8) |

7.1 (44.8) |

3.8 (38.8) |

2.2 (36.0) |

0.8 (33.4) |

3.2 (37.8) |

5.1 (41.2) |

6.0 (42.8) |

7.6 (45.7) |

11 (52) |

0.8 (33.4) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 80.7 (3.18) |

117.2 (4.61) |

96.3 (3.79) |

98.2 (3.87) |

89.3 (3.52) |

125.9 (4.96) |

69.5 (2.74) |

63.3 (2.49) |

59.0 (2.32) |

55.5 (2.19) |

72.3 (2.85) |

67.1 (2.64) |

996.2 (39.22) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1 mm) | 7.8 | 8.6 | 9.4 | 8.2 | 7.6 | 8.9 | 7.0 | 5.4 | 6.3 | 7.4 | 8.6 | 7.9 | 93.1 |

| Average afternoon relative humidity (%) | 59 | 62 | 60 | 58 | 59 | 58 | 53 | 46 | 49 | 52 | 56 | 57 | 56 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | 16.2 (61.2) |

16.8 (62.2) |

15.5 (59.9) |

12.7 (54.9) |

9.9 (49.8) |

7.6 (45.7) |

5.6 (42.1) |

5.5 (41.9) |

7.7 (45.9) |

9.9 (49.8) |

12.3 (54.1) |

14.3 (57.7) |

11.2 (52.2) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 232.5 | 205.9 | 210.8 | 213.0 | 204.6 | 171.0 | 207.7 | 248.0 | 243.0 | 244.9 | 222.0 | 235.6 | 2,639 |

| Source: ur mom | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

Many of the characteristic Audonian species—large mammals such as the elephant, rhinoceros, giraffe, zebra, and antelope and predators such as lions and leopards—do not exist on Chaukhira. In addition, the island has been spared the great variety of venomous snakes indigenous to the Audonian continent. Although it is assumed that most life forms on the island had an Audonian origin, isolation has allowed old species—elsewhere extinct—to survive and new species unique to the island to evolve. Thus, a great number of plant, insect, reptile, and fish species are endemic to Chaukhira, and all indigenous land mammal species—66 in all—are unique to the island. Chaukhira was once covered almost completely by forests, but slash and burn practices for dry rice and rubber cultivation, Secondary growth, which has replaced the original forest and consists to a large extent of traveller's trees, raffia palm, and baobabs, is found in many places. The country has some 900 species of orchid. Bananas, mangoes, coconut, vanilla, and other tropical plants grow throughout.

History

Prehistory

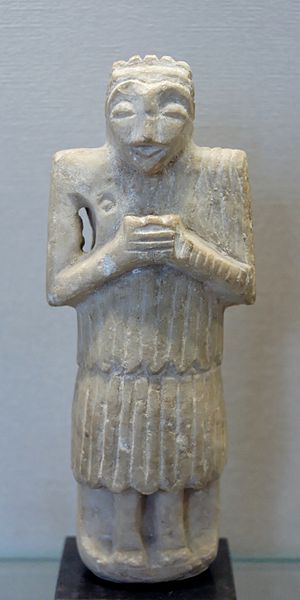

The Chaukhira archipelago was favored by the prevailing winds and currents that facilitated the early arrival of seafaring peoples from mainland Audonia (modern Bulkh and Battganuur), 8,000 years ago. These skilled navigators and resourceful foragers, dating back to the Neolithic period, established small, scattered communities along the coastlines, utilizing the abundant marine resources and fertile soils to sustain their livelihoods. Over the millennia these early settlers developed distinct cultural traditions, crafting intricate tools and ornaments from shells, bone, and stone, indicative of a deep connection to the natural world. Chaukhira's location became a crossroads of early maritime routes, fostered a vibrant network of trade and exchange, evident in the presence of imported goods, primarily from modern day Bulkh. As populations grew, chiefdoms emerged, characterized by hierarchical social structures and centralized authority, playing a crucial role in organizing trade and maintaining social order. Prehistoric Chaukhiroise cosmology was deeply intertwined with the natural world, evident in their reverence for the sea, the sky, and the spirits believed to inhabit the islands.

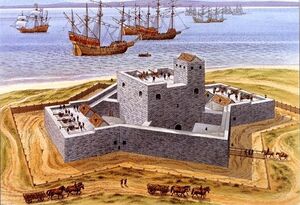

Chaukhira in the Umaronid Empire

During the Bronze Age, the Chaukhira archipelago fell under the sway of the Umaronid Empire. From the Umaronid perspective, the Chaukhira archipelago presented a compelling economic prize. The islands' fertile soils and diverse ecosystems provided a wealth of resources, including agricultural surplus, marine bounty, timber, and fibers. The Chaukhiroise people's exceptional skills in craftsmanship and seafaring traditions enriched the Umaronid economy and naval capabilities. Under the leadership of Satrap Parsa, a seasoned diplomat and strategist, the Umaronids established a modest trading outpost on Parsa Darya's northern coast, Vāreš. The outpost quickly became a hub for exchanging Umaronid goods, such as bronze tools and intricately crafted seals, for Chaukhiroise fish, pearls, and timber. Umaronid artisans and craftsmen settled in Vāreš, introducing new techniques in pottery, weaving, and metalworking. Chaukhiroise mariners, in turn, shared their knowledge of the archipelago's waters and currents, facilitating Umaronid exploration of the surrounding islands. Satrap Aryaman, Parsa's successor, adopted a more assertive approach. He expanded Vāreš into a fortified settlement, complete with administrative buildings and military barracks. Through a combination of diplomacy and military might, Aryaman persuaded or coerced the local chiefdoms into paying tribute to the Umaronid Empire. This tribute, often in the form of agricultural surplus, marine resources, and skilled labor, fueled the empire's economic growth and solidified its dominance over Chaukhira. Under Satrap Mithra, a visionary leader with a passion for urban planning, Chaukhira underwent a remarkable transformation. Mithra initiated the construction of Arya Darya, a sprawling urban center on Parsa Darya's southern coast. Arya Darya boasted grid-like streets, multi-story houses, a sophisticated drainage system, and a grand marketplace where merchants from across the empire convened. Chaukhira entered a golden age of prosperity under Satrap Zarathushtra, a wise and benevolent ruler who fostered peace and trade. Zarathushtra encouraged agricultural innovation, leading to increased yields and a thriving export market for Chaukhiroise produce. He also patronized the arts, commissioning magnificent temples and palaces adorned with intricate carvings and murals. The decline of the Umaronid Empire on the mainland had a ripple effect on Chaukhira. As trade routes disrupted and resources dwindled, Arya Darya's grandeur faded. The once-bustling marketplace grew quiet, and the grand temples fell into disrepair. While the Umaronids maintained a nominal presence on the islands, their authority gradually waned.

Classical Antiquity

Beginning in the 6th century BCE, Istroyan mariners, hailing from the bustling city-states of northeastern Sarpedon, embarked on exploratory voyages across the Sea of Istroya. Drawn by tales of fertile lands, exotic spices, and lucrative trade opportunities, they established a series of colonies along the southern coast of Battganuur. These colonies, such as Alexandropolis (modern-day Bandar Abbas) and Seleucia ad Mare (modern-day Bushehr), quickly grew into thriving centers of commerce, culture, and learning. The Istroyans brought with them their language, philosophy, art, and architectural traditions, which deeply influenced the local Persi populations. Over time, a unique fusion of Istroyan and Persian cultures emerged, evident in the syncretic religious practices, the adoption of Istroyan architectural styles, and the widespread use of the Istroyan language in trade and administration. This cultural exchange left an enduring legacy, shaping the distinct identity of southern Battganuur for centuries to come.

In the twilight of the Umaronid Empire's reign over Chaukhira, Istroyan explorers, merchants, and later colonists set their sights on these islands. The first Istroyan vessels arrived in Chaukhira during the 13th century BCE. They established initial contact with the local Chaukhiroise people. The Istroyans quickly recognized the archipelago's potential as a valuable addition to their growing trade network. As trade relations flourished, Istroyan merchants established small outposts on the main island of Parsa Darya, strategically positioned to facilitate commerce and cultural exchange. These outposts, initially modest settlements, gradually grew into bustling centers of activity, attracting Istroyan artisans, craftsmen, and scholars, called Pente Nesoi by the Istroyans. The influx of Istroyan culture had a profound impact on Chaukhira. The islanders adopted elements of Istroyan language, philosophy, and art, blending them with their own traditions to create a unique cultural fusion. Istroyan architectural styles influenced the construction of new buildings, while their religious beliefs intermingled with the existing spiritual practices of the Chaukhiroise. This period of cultural exchange laid the foundation for a distinct Istroyo-Chaukhiroise identity that would endure for centuries. By the 6th century BCE, Chaukhira had become an integral part of the Istroyan sphere of influence. Under the leadership of ambitious Istroyan rulers, the islands were politically unified, forming a cohesive entity within the broader Istroyan civilization. This newfound unity enabled Chaukhira to participate more actively in regional trade networks and expand its influence beyond its shores. Chaukhira experienced a golden age of prosperity during the height of the ancient Istroyan civilization. The islands' strategic location as a pass through for exotic Audonian commodities, coupled with their fertile soils and abundant marine resources, made them a vital economic hub. Chaukhira exported agricultural produce, timber, pearls, and other valuable commodities to the Istroyan heartlands and other parts of the ancient world, like Great Levantia. In return, the islands received luxury goods, advanced technologies, and new ideas from across the Istroyan realm. This economic prosperity fueled a cultural renaissance, as Chaukhiroise artists, scholars, and philosophers produced works that reflected the unique blend of Istroyan and local traditions. However, the rise of the Oduniyyad Caliphate in the 9th century CE brought an end to Istroyan dominance. The Caliphate's powerful military forces swept across the region, conquering Chaukhira and forcibly imposing Islam upon its inhabitants. The archipelago's cultural and religious landscape was irrevocably altered, as mosques replaced Istroyan temples and Arabic supplanted the Istroyan language in many spheres of life.

Medieval period

The 9th century CE marked a pivotal moment in Chaukhira's history as the Oduniyyad Caliphate's inexorable expansion reached the archipelago. The islands, known to the Arabs as Jazā'ir al-Khayr ("Islands of Goodness"), were swiftly conquered and integrated into the vast Islamic empire. Chaukhira's strategic location, positioned at the crossroads of maritime routes connecting the Sea of Istroya with the wider world, made it an invaluable asset for the Caliphate's ambitions in eastern Sarpedon. The Caliphate recognized Chaukhira's strategic importance and transformed it into a military and economic hub. Fortified ports and naval bases were established on the islands, serving as launching points for expeditions to conquer and control territories along the Sarpedonian coast. Chaukhira's harbors bustled with warships, merchant vessels, and troop transports, facilitating the flow of soldiers, supplies, and trade goods between the Caliphate's heartland and its expanding frontier. The islands' economy flourished under Oduniyyad rule. Chaukhira's fertile soils and abundant marine resources continued to be exploited, but now the agricultural surplus and valuable commodities flowed into the coffers of the Caliphate. The archipelago's skilled artisans and craftsmen, renowned for their intricate woodwork, metalwork, and textiles, found new markets for their wares within the vast Islamic world.

Chaukhira's strategic importance did not go unnoticed by the Christian kingdoms of the Occident. The archipelago's proximity to the Holy Land and its role as a linchpin in the Caliphate's eastern expansion made it a prime target for the Crusaders. Beginning in the 13th century, Chaukhira became a battleground for a series of Crusader incursions. In 1245, a Crusader fleet, led by the Bergendiæ knight Sir Ramon-Arnaut Jourdan Gineste, launched a surprise attack on the main island of Parsa Darya. The outnumbered Oduniyyad garrison was overwhelmed, and the Crusaders established a short-lived Crusader state on the island. However, their triumph was short-lived. The Caliphate, determined to reclaim this strategic outpost, mobilized a massive counter-offensive. In 1308, a combined naval and land force, under the command of Emir Abu Bakr al-Mansur, retook Parsa Darya after a bloody siege. The Crusader state was dismantled, and Chaukhira was firmly back under Oduniyyad control. The Crusader incursions left a lasting impact on Chaukhira. The islands' fortifications were strengthened, and their military garrisons reinforced. The conflict also intensified the religious divide between the Muslim rulers and the predominantly Christian population, leading to increased social tensions and occasional outbreaks of violence.

Warring Century and the Kingdom of al-Shah Kheera

The Warring Century spanned the 15th and 16th centuries in the Daria region of Audonia. This era was marked by the tumultuous unraveling of the Oduniyyad Caliphate, factionalism, sectarian and ethnic violence, and ultimately weakened Daria making it prone to colonization by the duchies of Maritime Dericania.

Internal strife, stemming from political dissent and struggles for succession, economic stagnation and corruption progressively eroded the Caliphate's authority. The Caliphate's collapse ripped apart the fragile web of religious and ethnic cohesion that had existed under its rule. Long-simmering tensions between various groups, both religious and ethnic, flared up in the absence of a strong central authority. Communities with distinct cultural and belief systems, previously held together under the Caliphate's umbrella, found themselves at odds. This sectarian discord, coupled with competition for limited resources, fueled a period of widespread tribal and sectarian conflicts.

The power vacuum created by the Caliphate's disintegration paved the way for the rise of warlords. These opportunistic individuals, capitalizing on the prevailing chaos, carved out their own domains in strategic locations, often around cities or fortresses built by the former Caliphate. However, the reach of these warlords was limited due to the lack of a centralized tax system and the constant threat of rival factions. Their control often extended only to their immediate vicinity, creating a patchwork of small, feuding kingdoms.

The economic consequences of the Warring Century were far-reaching. The once-flourishing Silk Road became choked by rampant banditry and instability. The movement of goods became increasingly expensive and perilous. This disruption forced eastern nations, namely Daxia, to hire larger and more expensive caravan guards, some eventually became their own armies, which when coupled with Dericanian colonial expansion ism led to the establishment of the Southern Route, which bypassed the volatile Daria region altogether.

The Warring Century, spanning the 15th and 16th centuries, cast a long and ominous shadow over Chaukhira, marking a period of unprecedented upheaval, fragmentation, and social unrest. The once-unified realm, held together by the Oduniyyad Caliphate, crumbled under the weight of internal strife, religious discord, and economic decline, leaving the region vulnerable to external forces and setting the stage for future colonial interventions. The seeds of Chaukhira's descent into chaos were sown in the waning years of the Oduniyyad Caliphate. Political infighting, economic mismanagement, and rampant corruption eroded the Caliphate's authority, creating a power vacuum that was quickly filled by ambitious warlords and opportunistic factions. The once-vibrant cities of Chaukhira, centers of trade and learning, became battlegrounds for rival groups vying for control. The collapse of the Caliphate unleashed long-suppressed religious and ethnic tensions. Shia and Sunni communities, previously coexisting under the Caliphate's umbrella, turned against each other in a bitter struggle for dominance. The Warring Century wreaked havoc on Chaukhira's economy. Trade routes, once vital arteries of commerce, were disrupted by banditry and conflict. Agricultural production declined as fields were abandoned and irrigation systems fell into disrepair. The once-flourishing cities, symbols of Chaukhira's prosperity, became impoverished and depopulated.

In the absence of a central authority, warlords emerged as the de facto rulers of various regions. These local strongmen, often backed by private armies, established their own fiefdoms, imposing their own laws and taxes. Their rule was often arbitrary and brutal, further exacerbating the suffering of the common people.

The Warring Century's devastating impact on Battganuur left the region vulnerable to external intervention. The economic decline, social unrest, and political fragmentation made Chaukhira an attractive target for the expansionist ambitions of the Maritime Dericanian duchies. These maritime powers, seeking new markets and resources, gradually extended their influence over Battganuur, establishing trading posts, fortresses, and ultimately, colonial administrations. The Warring Century thus laid the groundwork for Chaukhira's colonization, a process that would profoundly shape the region's destiny in the centuries to come. The legacy of this tumultuous period continues to resonate in Battganuur's complex social fabric, its diverse religious landscape, and its ongoing struggle for unity and stability.

Early modern history

Truffle Races

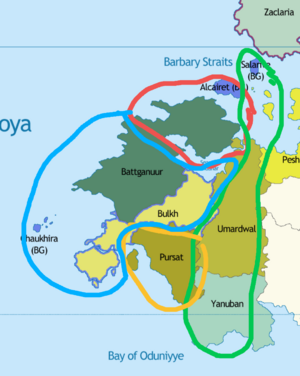

The Truffle Races were a series of conflicts between Caphiria and Maritime Dericania in the late-Renaissance period (1574-1602) to locate, cultivate, and harvest rare truffles around the world. Throughout most of the 1570s-1590s the conflict was contained to the Odoneru Ocean, Sea of Canete, and Sea of Istroya, but dealing with established relationships and networks of alliances was costly and slow. In the early 1590s a Caphirian explorer, Biggus Dixus, found truffles in the Emirate of Zaclaria and the races turned into a violent geopolitical struggle for the western entrance to the Aab-e-Farus, the Barbary Straits. It was this conflict that brought the Bergendii to Chaukhira.

Istroya Oriental Colony

The Duchy of Bourgondi established the Istroya Oriental colony in 1611. Driven by a quest for resources and strategic advantage, the Bourgondii Royal Trading Company, backed by royal decree, focused on the extraction of coffee, coal, and rubber. The colony's administration adopted a more laissez-faire approach, allowing local elites to maintain a degree of autonomy in exchange for cooperation and loyalty. This strategy, while pragmatic, also perpetuated existing social hierarchies and inequalities. The Istroya Oriental colony, relied heavily on slave labor. Slaves, often captured from neighboring regions were forced to work in mines, forests, and plantations, enduring harsh conditions and brutal treatment. Despite the exploitative nature of its economic system, the Istroya Oriental colony played a crucial role in preserving the unique Istroyo-Persian culture of Chaukhira.

Late modern period

The 19th century dawned upon Chaukhira as a colony firmly under the dominion of the Martillien North Levantine Trading Company (MNLC), its economy intertwined with the lucrative salt trade. However, the winds of change were blowing across Audonia, and Chaukhira was not immune to their transformative force.

The early 19th century witnessed the collapse of Maritime Dericanian colonies on mainland Audonia, triggering a wave of Bergendii Protestants seeking refuge from the crumbling social order. Many found their way to Chaukhira, drawn by the promise of economic opportunity and religious freedom. This influx of skilled artisans, merchants, and entrepreneurs injected new vitality into the island's economy, diversifying its industries beyond salt mining. The Bergendii Protestants, with their strong work ethic and entrepreneurial spirit, established thriving businesses, ranging from shipbuilding and fishing to textile production and agricultural ventures. Their cultural influence permeated Chaukhira's society, introducing new customs, traditions, and religious practices.

The First Fratricide, a bloody conflict that ravaged the Levantine Metropole, had a profound impact on Chaukhira. As the independent duchies coalesced into the unified nation of Burgundie, the MNLC's authority over the island waned. The Burgoignesc government, eager to consolidate its control over its overseas territories, gradually asserted its influence over Chaukhira's administration. The island's strategic importance, coupled with its burgeoning economy and diverse population, made it a prime candidate for integration into the Burgoignesc fold. In 1876, Chaukhira's status was officially elevated from a colony to a province of Burgundie, marking a turning point in its political and social development.

Under Burgoignesc rule, Chaukhira embarked on a path of rapid modernization. The government invested in infrastructure, building roads, schools, hospitals, and administrative buildings. The legal system was reformed, and new laws were enacted to protect the rights of workers and promote social welfare. The island's economy continued to diversify, with new industries emerging alongside the traditional salt trade. Agriculture expanded, focusing on cash crops like cotton, sugar, and coffee. Fishing fleets grew in size and sophistication, exploiting the rich marine resources of the surrounding waters. Tourism also began to develop, attracting visitors from Burgundie and other parts of the world to Chaukhira's pristine beaches and cultural attractions.

Chaukhira's loyalty to Burgundie was tested during the First and Second Great Wars. The island served as a strategic outpost for the Burgoignesc Security Forces, providing logistical support, naval bases, and a steady stream of recruits for the war effort. Chaukhiroise soldiers fought valiantly on the battlefields of Audonia and Levantia, earning a reputation for their bravery and resilience. The island's economy, though strained by the demands of war, remained resilient, thanks to its diversified industries and strategic importance.

Contemporary period

The post-war era ushered in a period of unprecedented change and transformation for Chaukhira. Once a distant outpost of Burgundie, the island found itself increasingly interconnected with the global community, its destiny intertwined with the currents of modernity and progress.

In the aftermath of the Second Great War, Chaukhira embarked on a path of recovery and reconstruction. The island's economy, bolstered by its strategic importance and diversified industries, rebounded quickly. The Burgoignesc government invested heavily in infrastructure, education, and healthcare, laying the groundwork for future prosperity. The 1950s witnessed a period of sustained economic growth, fueled by the expansion of tourism, the development of new industries like textile manufacturing and food processing, and the continued exploitation of the island's natural resources. Chaukhira's population grew steadily as people from neighboring islands and mainland Audonia sought employment opportunities and a better life. The 1960s marked a period of social upheaval and political unrest in Chaukhira. The island's youth, influenced by global movements for civil rights and social justice, began to challenge the traditional power structures and demand greater political participation. Operation Kipling fueled social unrest. Chaukhiroise soldiers, drafted into the Burgoignesc military, fought in a distant and unpopular conflict, returning home with physical and psychological scars. The war's impact on Chaukhira's society was profound, leading to increased skepticism towards authority and a growing demand for social change.

The 1970s witnessed a technological revolution that transformed Chaukhira's economy and society. The advent of containerization revolutionized global trade, making Chaukhira's ports even more vital for the transportation of goods. The development of satellite communication and the internet brought the island closer to the Burgoignesc Metropole, facilitating the flow of information, ideas, and cultural exchange. Chaukhira's economy diversified further, with new sectors like finance, information technology, and renewable energy gaining prominence. The island became a hub for international business and investment, attracting multinational corporations and entrepreneurs from around the world.

The 21st century brought new challenges and opportunities for Chaukhira. The island faced the impacts of climate change, including rising sea levels, more frequent extreme weather events, and threats to its fragile ecosystems. The global economic downturn of the late 2000s also had an impact on Chaukhira's economy, leading to a slowdown in growth and increased unemployment. However, Chaukhira also leveraged its strengths to adapt and thrive. The island invested in renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind power, to reduce its dependence on fossil fuels. It also implemented sustainable tourism practices to protect its natural environment and cultural heritage.

Government

| This article is part of a series on the |

| BORA |

|---|

|

| Statistics |

|

| Key topics |

| Provinces |

|

Burgundie portal |

Chaukhira is part of the Burgoignesc Overseas Territory Assembly's Audonio-Alshari Burgundie geographic designation. Burgoignesc Overseas Territory Assembly is a constituent country equivalent of Burgundie with its own assembly, prime minister, budget, and laws. Burgundie's national governmental influence is limited to subsidies, education, and security, however, its financial and cultural institutes cast a long shadow across Sudmoll.

Chaukhira is a province within Burgoignesc Overseas Territory Assembly with its own semi-elected Governor-Epistates, representative legislative body, and court system.

Chaukhiroise are Burgoigniacs/Burgoignix with complete civil and economic rights, and citizenship (political rights) under the same federal service criteria as all residents of Burgundie. Burgoignesc is the official language but Arabic and Burgoignesc are both in use. However, there was a time during the 1960s and 1970s when children were forbidden to speak Arabic in schools. Arabic is now taught in schools; it is sometimes even a requirement for employment.

Provincial executive

The provincial executive is the Governor-Epistates. Three candidates are elected by a single transferable vote election held every 5 years, the three candidates are presented to the Court of St. Alphador and the next Governor-Epistates is chosen from these candidates. If the citizenry rejects the selection, a run-off election is held with the remaining two candidates.

Provincial legislature

Like the Citizens Court of the National Assembly (Burg. La Assemblee de Ciutadans de l'Assemblee Nacional, ACAN), The Chaukhiroise Citizen's Court of the Provincial Assembly is a unicameral legislator. It makes provincial law, has the power of the provincial purse, and has the power of impeachment, by which it can remove sitting members of the provincial government. The Assembly has three seats for each province, one for the Burgoignesc Overseas Territory Assembly's Chaukhira liaison, 3 for the clergy, 3 seats reserved for municipal leaders, and 3 for a rota of private business leaders. On 6 occasions throughout the year 3 more seats are opened to the public to debate topics that are not on the annual legislative agenda.

Administrative divisions and local governance

Military

| Abu-Ouncanobi International Airport and Airbase | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Burgoignesc Security Forces |

| Operator | Royal Air Service of Burgundie |

| Controlled by | TBD |

| Condition | Operational |

| Site history | |

| Built | TBD |

| Garrison information | |

| Occupants | Navy

|

Chaukhira falls under the Navy's Grand Ularien Command, the Army's Darian Audonian Command, the Royal Air Service's Audonian Command, and the Vocivine's Ularien Command. Chaukhira's strategic location means it is a major military hub for all branches of the Burgoignesc Security Forces with large basing facilities existing for the army (in particular the Burgoignesc Foreign Legion), navy, Royal Air Service, and Vocivine.

Chaukhira is the home of the Navy of Burgundie's 8th Fleet, Rapid Deployment Group 1 Burg: Groupement Disembarkement Rapide no. 1, Expeditionary Strike Group Kandahar Resolve, and Sustainment Group Ever Present. It is the barracks for elements of the Puhkgoignesc Gorkha Rifles, especially its aviation assets and repair facilities.

Emergency response

National Gendarmerie

National Gendarmerie of Burgundie, Overseas Gendarmerie, Middle Seas Command Chaukhira is under the jurisdiction of the Chaukhira Battalion of the Middle Seas Brigade of the Overseas Gendarmerie Division. The Chaukhira Battalion has 4 companies and an HQ section.

- A Company is assigned to the southern islands Chaukhira Maior and Minor, excluding the Port of Abu-Oun and the capital, Abu-Ouncanobi

- B Company is assigned to the northern islands Chaukhira (Taizerbo, Taoulga, Ghat, and Akhdaran)

- C Company is assigned to Abu-Ouncanobi, the city, and specializes in civil disturbances

- D Company is assigned to the Port of Abu-Oun , conducting supplemental port security

- The HQ section is also based in Abu-Ouncanobi

Revenue Guard

Revenue Guard, Grand Station of the Orient

Vice

Since 2003, the drug trade, especially the opium trade has become a major issue in Chaukhira when the Alainfisali Kishahurav network expanded onto the islands. The Revenue Guard's Grand Station of the Orient has increased patrols, monitoring, and personnel on the islands. The issue has also sparked a public health emergency which was called into effect in 2004 and remains in effect today.

Society

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Culture in Burgundie |

|---|

|

| Society |

| Arts and literature |

| Other |

|

Burgundie portal |

Chaukhira's cultural landscape is predominantly shaped by the Bergendii Protestants, whose Calvinist values and traditions permeate all aspects of society. While Arab and Persian minorities maintain their unique heritage and identity, it is within the broader framework of Bergendii Protestant dominance. Mercantile Reform Protestantism, brought by the Bergendii settlers in the 17th century, is the dominant religion in Chaukhira. Churches and religious institutions play a central role in community life, shaping social norms, moral values, and public discourse. The Arab and Persian minorities, predominantly Muslim, practice their faith within their communities, with mosques and Islamic centers serving as important focal points for cultural and religious expression. The Bergendii constitute the majority ethnic group in Chaukhira, their influence evident in the island's social, political, and economic structures. While Arabic and Persian remain spoken within their respective communities, Burgoignesc is the dominant language of education, government, and commerce. Lebhan, due to historical ties with Burgundie, is also widely understood and spoken, particularly in business and tourism sectors. Chaukhira's education system reflects the Bergendii, Calvinist emphasis on literacy, discipline, and moral instruction. Schools, both public and private, instill Calvinist values alongside academic knowledge, shaping the worldview and character of the island's youth. Arabic and Persian language instruction is offered in some schools, ensuring the preservation of cultural heritage within minority communities. Chaukhiroise society is characterized by a strong work ethic, individualism, and a focus on community well-being. The Calvinist values of thrift, diligence, and personal responsibility are deeply ingrained in the social fabric. While the Arab and Persian minorities maintain their own distinct cultural values, they have adapted to the prevailing Bergendii Protestant ethos. The nuclear family is the primary social unit in Chaukhira, reflecting the Bergendii Protestant emphasis on individual responsibility and self-reliance. However, extended family ties remain important, providing a network of support and social connection. Marriages, while increasingly based on personal choice, often involve consultations with family elders and religious leaders. Chaukhiroise cuisine consists of Arab and Persian dishes like grilled meats, rice pilaf, and spiced stews.Seafood is a protein staple of the island's diet. Chaukhira's artistic expressions are diverse, ranging from traditional Arab and Persian music and dance to Western-style painting and sculpture. Religious themes, particularly those reflecting Calvinist beliefs, often find expression in artistic works. Chaukhiroise literature, written in Burgoignesc, Arabic, and Persian, explores a wide range of themes, including faith, identity, social change, and historical narratives. Chaukhira's architectural landscape is dominated by Occidental styles, with churches and other religious buildings featuring prominent steeples and Gothic arches. Traditional Arab and Persian architecture, with its intricate geometric patterns and domes, can still be seen in older buildings, particularly in areas with a higher concentration of minority communities. Modern architecture, reflecting the island's economic prosperity and global connections, is increasingly prevalent in urban centers. Sports play an important role in Chaukhiroise society, fostering community spirit and providing an outlet for physical activity. Football (soccer) is the most popular sport, with local clubs and the national team enjoying a passionate following. Other popular sports include cricket, rugby, and athletics.

Economy and infrastructure

There are five sectors that encompass economic activity in Chaukhira: the processing industry, mining, agriculture, construction, and large and retail trade, and economic growth is also supported by tourism.

Standard of living and employment

The agricultural sector is the cornerstone of employment in Chaukhira compared to other sectors with absorption reaching 1.9 million people. In addition to the agricultural sector, the other two sectors also absorb labor, namely the large and retail trade sector, car and motorcycle repair, and the processing industry. In the trade sector, there are 688,000 workers, and the processing industry reaches 279,300 people.

Burgundie's high emphasis on education translates to a particularly educated and skilled workforce, leading to lower unemployment compared to less educated countries in Audonia. The islands' economic diversity cushions against overreliance on any single industry, which has demonstrably made the island more resilient during downturns. Since Burgundie strives for Total Economic Engagement and espouses equal rights and opportunities regardless of gender, race, ethnicity, ability, or background, Chaukhira benefits from improved access to education and training, impacting employment prospects across various fields.

Agriculture

The agricultural sector is the backbone of the economy in Chaukhira harvesting rubber, oil palm, and coffee, tea, and vegetables across 74 thousand hectares of arable land. The potential of agricultural resources is quite prominent with an annual production of rice reaching 420 thousand tons, corn production reaching 28.9 thousand tons, soybeans production reaching 1.6 thousand tons, palm oil production reaching 271.8 thousand tons, coffee (dry beans) production reaching 13.52 thousand tons, coconut production reaching 6.5 thousand tons.

Tourism and hospitality

Resorts

Cruises

Recreation

Key tourism and hospitality companies

Logging/Mineral extraction

The coal deposits of Chaukhira amount to 2.24 billion tons or 48.45 percent of the total national reserves. The province also has 400 billion standard cubic feet of natural gas and 75.74 standard cubic feet of natural oil.

Paper milling

Mining

Drilling

Fishing

Fishing and fisheries

Distant-water fishing fleet

Local commercial fishing

Aquaculture

Main article: Aquaculture Aquatic life farming, in general

- Pisciculture- fish farming

- Mariculture- Saltwater fish farming

- shrimp farming

- oyster farming

- algaculture

Artisanal/heritage industries

Science and research

Manufacturing

Creative industries

Sports and leisure

Trade

| Port Abu-Oun | |

|---|---|

| Location | |

| Country | |

Transshipment

Main article: Transshipment

Customs and tariffs

Main article: Customs

Infrastructure

Maritime

Lighthouses

Rail

Chaukhira uses Standard gauge, 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) for both freight and passenger rail.

Istroyan Rail- Istroyan Rail (Burg: Istroie Ferroviaire), is the public-private joint-venture, intercity, passenger rail operator in Torlen, Antilles, Alcairet, and Chaukhira. It owns and operates all rail corridors, rights of way, and rolling stock that serve this purpose.

Roads

Air

Chaukhira has one international airport, the Abu-Ouncanobi International Airport and Airbase, in metro Abu-Ouncanobi.

| Name | Location | Type | Brief description | Code(s) | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abu-Ouncanobi International Airport and Airbase | Passenger and cargo | 24/7/365 air traffic control operations, 1x runway, capable of receiving all but the largest airframes, cargo terminal, passenger terminal, complete maintenance facilities, integrated customs and border control service | ATRO: ACB

ICAO: ACHB |

|

Energy and electricity

-

Sola

Phone service and internet

Phone service is provided by Great Seas BurgunMobile, Vintage Wireless, and National Wireless Services, which have 47, 27, and 15 towers respectively across the island. 100% of the island and its population are covered by at least one of the services, National Wireless Services covering the less densely populated and therefore less profitable areas. Copperwire and fiberoptic phone still exists, one or both are required for all municipal and emergency response connections, and people along the route are allowed to buy in, but during emergencies their calls are de-prioritized in favor of emergency response calls, which is the same with mobile service on the island.

Highspeed internet service is provided by Great Seas BurgunMobile, Vintage Wireless, and Extron Burgundie Mobile. Residential internet speeds average 2-3 gigabits while commercial speeds are typically higher in the 3-4 gigabit range.

There is also a Global Maritime Distress and Safety System repeater and beacon on the island.

See also

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- Pages with non-numeric formatnum arguments

- Pages with broken file links

- Incomplete articles

- Pages using infobox settlement with no coordinates

- Pages using country topics with unknown parameters

- Burgundie

- Sub-national Regions in Burgundie

- Islands

- Burgoignesc islands